Analysis of RNA Modifications by Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

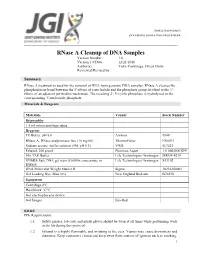

Rnase a Cleanup of DNA Samples Version Number: 1.0 Version 1.0 Date: 12/21/2016 Author(S): Yuko Yoshinaga, Eileen Dalin Reviewed/Revised By

SAMPLE MANAGEMENT STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE RNase A Cleanup of DNA Samples Version Number: 1.0 Version 1.0 Date: 12/21/2016 Author(s): Yuko Yoshinaga, Eileen Dalin Reviewed/Revised by: Summary RNase A treatment is used for the removal of RNA from genomic DNA samples. RNase A cleaves the phosphodiester bond between the 5'-ribose of a nucleotide and the phosphate group attached to the 3'- ribose of an adjacent pyrimidine nucleotide. The resulting 2', 3'-cyclic phosphate is hydrolyzed to the corresponding 3'-nucleoside phosphate. Materials & Reagents Materials Vendor Stock Number Disposables 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes Reagents TE Buffer, pH 8.0 Ambion 9849 RNase A, DNase and protease-free (10 mg/ml) ThermoFisher EN0531 Sodium acetate buffer solution (3M, pH 5.2) VWR 567422 Ethanol, 200 proof Pharmco-Aaper 111000200CSPP 50x TAE Buffer Life Technologies/ Invitrogen MRGF-4210 SYBR® Safe DNA gel stain (10,000x concentrate in Life Technologies/ Invitrogen S33102 DMSO) DNA Molecular Weight Marker II Sigma 10236250001 Gel Loading Dye, Blue (6x) New England BioLabs B7021S Equipment Centrifuge 4°C Heat block 37°C Gel electrophoresis device Gel Imager Bio-Rad EH&S PPE Requirements: 1.1 Safety glasses, lab coat, and nitrile gloves should be worn at all times while performing work in the lab during this protocol. 1.2 Ethanol is a highly flammable and irritating to the eyes. Vapors may cause drowsiness and dizziness. Keep containers closed and keep away from sources of ignition such as smoking. 1 SAMPLE MANAGEMENT STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE Avoid contact with skin and eyes. In case of contact with eyes, rinse immediately with plenty of water and seek medical advice. -

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 82 Convention on Biological Diversity

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 82 Convention on Biological Diversity 82 SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY FOREWORD To be added by SCBD at a later stage. 1 BACKGROUND 2 In decision X/13, the Conference of the Parties invited Parties, other Governments and relevant 3 organizations to submit information on, inter alia, synthetic biology for consideration by the Subsidiary 4 Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA), in accordance with the procedures 5 outlined in decision IX/29, while applying the precautionary approach to the field release of synthetic 6 life, cell or genome into the environment. 7 Following the consideration of information on synthetic biology during the sixteenth meeting of the 8 SBSTTA, the Conference of the Parties, in decision XI/11, noting the need to consider the potential 9 positive and negative impacts of components, organisms and products resulting from synthetic biology 10 techniques on the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, requested the Executive Secretary 11 to invite the submission of additional relevant information on this matter in a compiled and synthesised 12 manner. The Secretariat was also requested to consider possible gaps and overlaps with the applicable 13 provisions of the Convention, its Protocols and other relevant agreements. A synthesis of this 14 information was thus prepared, peer-reviewed and subsequently considered by the eighteenth meeting 15 of the SBSTTA. The documents were then further revised on the basis of comments from the SBSTTA 16 and peer review process, and submitted for consideration by the twelfth meeting of the Conference of 17 the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. -

U6 Small Nuclear RNA Is Transcribed by RNA Polymerase III (Cloned Human U6 Gene/"TATA Box"/Intragenic Promoter/A-Amanitin/La Antigen) GARY R

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 8575-8579, November 1986 Biochemistry U6 small nuclear RNA is transcribed by RNA polymerase III (cloned human U6 gene/"TATA box"/intragenic promoter/a-amanitin/La antigen) GARY R. KUNKEL*, ROBIN L. MASERt, JAMES P. CALVETt, AND THORU PEDERSON* *Cell Biology Group, Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology, Shrewsbury, MA 01545; and tDepartment of Biochemistry, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66103 Communicated by Aaron J. Shatkin, August 7, 1986 ABSTRACT A DNA fragment homologous to U6 small 4A (20) was screened with a '251-labeled U6 RNA probe (21, nuclear RNA was isolated from a human genomic library and 22) using a modified in situ plaque hybridization protocol sequenced. The immediate 5'-flanking region of the U6 DNA (23). One of several positive clones was plaque-purified and clone had significant homology with a potential mouse U6 gene, subsequently shown by restriction mapping to contain a including a "TATA box" at a position 26-29 nucleotides 12-kilobase-pair (kbp) insert. A 3.7-kbp EcoRI fragment upstream from the transcription start site. Although this containing U6-hybridizing sequences was subcloned into sequence element is characteristic of RNA polymerase II pBR322 for further restriction mapping. An 800-base-pair promoters, the U6 gene also contained a polymerase III "box (bp) DNA fragment containing U6 homologous sequences A" intragenic control region and a typical run of five thymines was excised using Ava I and inserted into the Sma I site of at the 3' terminus (noncoding strand). The human U6 DNA M13mp8 replicative form DNA (M13/U6) (24). -

Noncanonical Coproporphyrin-Dependent Bacterial Heme Biosynthesis Pathway That Does Not Use Protoporphyrin

Noncanonical coproporphyrin-dependent bacterial heme biosynthesis pathway that does not use protoporphyrin Harry A. Daileya,b,c,1, Svetlana Gerdesd, Tamara A. Daileya,b,c, Joseph S. Burcha, and John D. Phillipse aBiomedical and Health Sciences Institute and Departments of bMicrobiology and cBiochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602; dMathematics and Computer Science Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL 60439; and eDivision of Hematology, Department of Medicine, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT 84132 Edited by J. Clark Lagarias, University of California, Davis, CA, and approved January 12, 2015 (received for review August 25, 2014) It has been generally accepted that biosynthesis of protoheme of a “primitive” pathway in Desulfovibrio vulgaris (13). This path- (heme) uses a common set of core metabolic intermediates that way, named the “alternative heme biosynthesis” path (or ahb), has includes protoporphyrin. Herein, we show that the Actinobacteria now been characterized by Warren and coworkers (15) in sulfate- and Firmicutes (high-GC and low-GC Gram-positive bacteria) are reducing bacteria. In the ahb pathway, siroheme, synthesized unable to synthesize protoporphyrin. Instead, they oxidize copro- from uroporphyrinogen III, can be further metabolized by suc- porphyrinogen to coproporphyrin, insert ferrous iron to make Fe- cessive demethylation and decarboxylation to yield protoheme (14, coproporphyrin (coproheme), and then decarboxylate coproheme 15) (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). A similar pathway exists for protoheme- to generate protoheme. This pathway is specified by three genes containing archaea (15, 16). named hemY, hemH, and hemQ. The analysis of 982 representa- Current gene annotations suggest that all enzymes for pro- tive prokaryotic genomes is consistent with this pathway being karyotic heme synthetic pathways are now identified. -

Investigation of Overhauser Effects Between Pseudouridine and Water Protons in RNA Helices

Investigation of Overhauser effects between pseudouridine and water protons in RNA helices Meredith I. Newby* and Nancy L. Greenbaum*†‡ *Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and †Institute of Molecular Biophysics, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4390 Communicated by Michael Kasha, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, August 8, 2002 (received for review July 2, 2002) The inherent chemical properties of RNA molecules are expanded by posttranscriptional modification of specific nucleotides. Pseudouridine (), the most abundant of the modified bases, features an additional imino group, NH1, as compared with uri- dine. When forms a Watson–Crick base pair with adenine in an RNA helix, NH1 is positioned within the major groove. The pres- ence of often increases thermal stability of the helix or loop in which it is found [Hall, K. B. & McLaughlin, L. (1992) Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 1883–1889]. X-ray crystal structures of transfer RNAs [e.g., Arnez, J. & Steitz, T. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 7560–7567] have depicted water molecules bridging NH1 groups and nearby phos- phate oxygen atoms, but direct evidence for this interaction in solution has not been acquired. Toward this end, we have used a rotating-frame Overhauser effect spectroscopy-type NMR pulse sequence with a CLEAN chemical-exchange spectroscopy spin-lock pulse train [Hwang, T.-L., Mori, S., Shaka, A. J. & van Zijl, P. C. M. Fig. 1. Schematic structures of U and bases. R, ribose. The base is a uracil (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 6203–6204] to test for NH1–water rotated about the 3–6 ring axis, so that is has a COC base–sugar linkage and cross-relaxation effects within two RNA helices: (i) a complemen- an additional protonated ring nitrogen. -

Expanding the Genetic Code Lei Wang and Peter G

Reviews P. G. Schultz and L. Wang Protein Science Expanding the Genetic Code Lei Wang and Peter G. Schultz* Keywords: amino acids · genetic code · protein chemistry Angewandte Chemie 34 2005 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim DOI: 10.1002/anie.200460627 Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44,34–66 Angewandte Protein Science Chemie Although chemists can synthesize virtually any small organic molecule, our From the Contents ability to rationally manipulate the structures of proteins is quite limited, despite their involvement in virtually every life process. For most proteins, 1. Introduction 35 modifications are largely restricted to substitutions among the common 20 2. Chemical Approaches 35 amino acids. Herein we describe recent advances that make it possible to add new building blocks to the genetic codes of both prokaryotic and 3. In Vitro Biosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. Over 30 novel amino acids have been genetically Approaches to Protein encoded in response to unique triplet and quadruplet codons including Mutagenesis 39 fluorescent, photoreactive, and redox-active amino acids, glycosylated 4. In Vivo Protein amino acids, and amino acids with keto, azido, acetylenic, and heavy-atom- Mutagenesis 43 containing side chains. By removing the limitations imposed by the existing 20 amino acid code, it should be possible to generate proteins and perhaps 5. An Expanded Code 46 entire organisms with new or enhanced properties. 6. Outlook 61 1. Introduction The genetic codes of all known organisms specify the same functional roles to amino acid residues in proteins. Selectivity 20 amino acid building blocks. These building blocks contain a depends on the number and reactivity (dependent on both limited number of functional groups including carboxylic steric and electronic factors) of a particular amino acid side acids and amides, a thiol and thiol ether, alcohols, basic chain. -

The Human Ortholog of Archaeal Pus10 Produces Pseudouridine 54 in Select Trnas Where Its Recognition Sequence Contains a Modified Residue

Downloaded from rnajournal.cshlp.org on October 7, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The human ortholog of archaeal Pus10 produces pseudouridine 54 in select tRNAs where its recognition sequence contains a modified residue MANISHA DEOGHARIA,1 SHAONI MUKHOPADHYAY, ARCHI JOARDAR,2 and RAMESH GUPTA Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62901-4413, USA ABSTRACT The nearly conserved U54 of tRNA is mostly converted to a version of ribothymidine (T) in Bacteria and eukaryotes and to a version of pseudouridine (Ψ) in Archaea. Conserved U55 is nearly always modified to Ψ55 in all organisms. Orthologs of TrmA and TruB that produce T54 and Ψ55, respectively, in Bacteria and eukaryotes are absent in Archaea. Pus10 produces both Ψ54 and Ψ55 in Archaea. Pus10 orthologs are found in nearly all sequenced archaeal and most eukaryal genomes, but not in yeast and bacteria. This coincides with the presence of Ψ54 in most archaeal tRNAs and some animal tRNAs, but its absence from yeast and bacteria. Moreover, Ψ54 is found in several tRNAs that function as primers for retroviral DNA syn- thesis. Previously, no eukaryotic tRNA Ψ54 synthase had been identified. We show here that human Pus10 can produce Ψ54 in select tRNAs, including tRNALys3, the primer for HIV reverse transcriptase. This synthase activity of Pus10 is restrict- ed to the cytoplasm and is distinct from nuclear Pus10, which is known to be involved in apoptosis. The sequence GUUCAm1AAUC (m1A is 1-methyladenosine) at position 53–61 of tRNA along with a stable acceptor stem results in max- imum Ψ54 synthase activity. -

Pseudouridine Synthases Modify Human Pre-Mrna Co-Transcriptionally and Affect Splicing

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.29.273565; this version posted August 31, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect splicing Authors: Nicole M. Martinez1, Amanda Su1, Julia K. Nussbacher2,3,4, Margaret C. Burns2,3,4, Cassandra Schaening5, Shashank Sathe2,3,4, Gene W. Yeo2,3,4* and Wendy V. Gilbert1* Authors and order TBD with final revision. Affiliations: 1Yale School of Medicine, Department of Molecular Biophysics & Biochemistry, New Haven, CT 06520, USA. 2Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA. 3Stem Cell Program, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA. 4Institute for Genomic Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA. 5Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA. *Correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Eukaryotic messenger RNAs are extensively decorated with modified nucleotides and the resulting epitranscriptome plays important regulatory roles in cells 1. Pseudouridine (Ψ) is a modified nucleotide that is prevalent in human mRNAs and can be dynamically regulated 2–5. However, it is unclear when in their life cycle RNAs become pseudouridylated and what the endogenous functions of mRNA pseudouridylation are. To determine if pseudouridine is added co-transcriptionally, we conducted pseudouridine profiling 2 on chromatin-associated RNA to reveal thousands of intronic pseudouridines in nascent pre-mRNA at locations that are significantly associated with alternatively spliced exons, enriched near splice sites, and overlap hundreds of binding sites for regulatory RNA binding proteins. -

"Modified" RNA (And DNA) World

July editorial The "modified" RNA (and DNA) world A few months ago, as COVID-19 vaccinations were getting underway in the U.S., a non-scientist friend said he was uneasy because had heard that the RNA in them had been "doped". Leaning in, I asked "How?" (I knew of course, vide infra). "With some chemical" he replied. This struck me as a perfect storm of an educated, reasonably informed non- scientist being led astray by how the media often doesn't get it quite right, though we all recognize that too much detail can be narcoleptic. The art is to convey the science in just the right dose, as Lewis Thomas and Carl Sagan did for example (1). I told my friend what the "doping" was, using lay terms. He listened thoughtfully and then I came in with my final shot: nature is full of RNA that is "doped", and even DNA is as well. These chemical modifications are not done by mad scientists but the very biological systems in which these RNAs and DNAs reside, using their own enzymes. He left somewhat convinced and hopefully is now vaccinated. This encounter gave me the thought that I, and my readers, should take a step back and think about all the "modified" RNAs and DNAs out there. For transfer RNAs alone, there are 120 known base modifications, with their prevalence as high as 13 of the 76 nucleotides in human cytosolic tRNAtyr(2). N6- adenosine methylation of messenger RNA, discovered in 1974, has recently come to the fore, although not all experts agree on its functional significance (3,4). -

Chapter 3. the Beginnings of Genomic Biology – Molecular

Chapter 3. The Beginnings of Genomic Biology – Molecular Genetics Contents 3. The beginnings of Genomic Biology – molecular genetics 3.1. DNA is the Genetic Material 3.6.5. Translation initiation, elongation, and termnation 3.2. Watson & Crick – The structure of DNA 3.6.6. Protein Sorting in Eukaryotes 3.3. Chromosome structure 3.7. Regulation of Eukaryotic Gene Expression 3.3.1. Prokaryotic chromosome structure 3.7.1. Transcriptional Control 3.3.2. Eukaryotic chromosome structure 3.7.2. Pre-mRNA Processing Control 3.3.3. Heterochromatin & Euchromatin 3.4. DNA Replication 3.7.3. mRNA Transport from the Nucleus 3.4.1. DNA replication is semiconservative 3.7.4. Translational Control 3.4.2. DNA polymerases 3.7.5. Protein Processing Control 3.4.3. Initiation of replication 3.7.6. Degradation of mRNA Control 3.4.4. DNA replication is semidiscontinuous 3.7.7. Protein Degradation Control 3.4.5. DNA replication in Eukaryotes. 3.8. Signaling and Signal Transduction 3.4.6. Replicating ends of chromosomes 3.8.1. Types of Cellular Signals 3.5. Transcription 3.8.2. Signal Recognition – Sensing the Environment 3.5.1. Cellular RNAs are transcribed from DNA 3.8.3. Signal transduction – Responding to the Environment 3.5.2. RNA polymerases catalyze transcription 3.5.3. Transcription in Prokaryotes 3.5.4. Transcription in Prokaryotes - Polycistronic mRNAs are produced from operons 3.5.5. Beyond Operons – Modification of expression in Prokaryotes 3.5.6. Transcriptions in Eukaryotes 3.5.7. Processing primary transcripts into mature mRNA 3.6. Translation 3.6.1. -

Evaluation of the Quality, Safety and Efficacy of Messenger RNA

1 2 3 WHO/BS/2021.2402 4 ENGLISH ONLY 5 6 7 8 9 Evaluation of the quality, safety and efficacy of messenger RNA vaccines for 10 the prevention of infectious diseases: regulatory considerations 11 12 13 14 15 16 NOTE: 17 18 This draft document has been prepared for the purpose of inviting comments and suggestions on 19 the proposals contained therein which will then be considered by the WHO Expert Committee on 20 Biological Standardization (ECBS). The distribution of this draft document is intended to 21 provide information on the proposed document: Evaluation of the quality, safety and efficacy of 22 messenger RNA vaccines for the prevention of infectious diseases: regulatory considerations to a 23 broad audience and to ensure the transparency of the consultation process. 24 25 The text in its present form does not necessarily represent the agreed formulation of the 26 ECBS. Written comments proposing modifications to this text MUST be received by 17 27 September 2021 using the Comment Form available separately and should be addressed to 28 the Department of Health Products Policy and Standards, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue 29 Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. Comments may also be submitted electronically to the 30 Responsible Officer: Dr Tiequn Zhou at: [email protected]. 31 32 The outcome of the deliberations of the Expert Committee will be published in the WHO 33 Technical Report Series. The final agreed formulation of the document will be edited to be in 34 conformity with the second edition of the WHO style guide (KMS/WHP/13.1). -

The Crystal Structure of Biotin Synthase, an S-Adenosylmethionine-Dependent Radical Enzyme F

2-74 LIFE SCIENCES SCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS 2-75 The Crystal Structure of Biotin Synthase, an S-Adenosylmethionine-Dependent Radical Enzyme F. Berkovitch1, Y. Nicolet1, J.T. Wan2, J.T. Jarrett2, and C.L. Drennan1 1Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2Johnson Research Foundation and Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Pennsylvania BEAMLINE X25 The crystal structure of biotin synthase addresses how “AdoMet radical” enzymes, also called “Radical SAM” enzymes, use an Fe S cluster and S-adenosyl-L-methionine to 4 4 Funding generate organic radicals. Biotin synthase catalyzes the radical-mediated insertion of National Institutes of Health; Searle Scholars Program; sulfur into dethiobiotin (DTB) to form biotin (vitamin B8). The structure places the substrates, i.e. DTB and AdoMet, between the Fe S cluster (essential for radical gen- Cecil and Ida Green Career 4 4 Development Fund; Lester eration) and the Fe2S2 cluster (postulated to be the source of sulfur), with both clusters Wolfe Predoctoral Fellowship; in unprecedented coordination environments. Cellular, Biochemical, and Molecular Sciences training Biotin is an essential vitamin that plays a ubiquitous role in human growth and grant; U.S. Department of Energy; National Institute of metabolism. Biotin deficiency results in skin lesions, abnormal fat distribution, General Medical Sciences neurological symptoms, and immunodeficiency. A low biotin level has also been correlated to an increased incidence of type II diabetes mellitus. Biotin is a valuable Publication commercial commodity, used as an additive in food, health, and cosmetic prod- F. Berkovitch, Y. Nicolet, J.T. Wan, J.T. Jarrett, and ucts, and as a research tool in the biochemical sciences.