Active Mobility: Bringing Together Transport Planning, Urban Planning, and Public Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walkable Communities Expert Roundtable Report

Walkable Communities Expert Roundtable Report Association of State and Territorial Health Officials Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction to ASTHO .................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction to Walkable Communities ......................................................................................................... 4 Meeting Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Expert Recommendations ............................................................................................................................... 6 Successes, Challenges, and Current Work ...................................................................................................... 8 Research Gaps and Needs for Promoting Policies and Practices ................................................................. 13 Overall Recommendations ............................................................................................................................ 15 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................................................... 16 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................ -

On Guard- AGAINST DIABETES

On Guard AGAINST DIABETES Information on Diabetes for Persons With Disabilities ACTIVE LIVING ALLIANCE FOR CANADIANS WITH A DISABILITY www.ala.ca Acknowledgements Funding for this publication was provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not neces- sarily reflect the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada. The Active Living Alliance for Canadians with a Disability would like to thank the Canadian Diabetes Association for their contributions to this document. Through research, education, service, and advocacy, the Canadian Diabetes Association works to prevent type 2 diabetes and to improve the quality of life for those affected by type 1, type 2 and gestational diabetes. For more information please visit http://www.diabetes.ca . The development of this publication was supported by: Dianne Bowtell: Canadian Therapeutic Recreation Association, www.canadian- tr.org Lynn Chiarelli: Project Coordinator, Canadian Public Health Association Douglas G. Cripps, M.A: Chair - Active Living Alliance for Canadians with a Disability, Instructor III/Fieldwork Coordinator, Co-Coordinator Bachelor of Health Studies Program Faculty of Kinesiology and Health Studies University of Regina Traci Walters: National Director, Independent Living Canada (formerly the Canadian Association of Independent Living Centres) On Guard AGAINST DIABETES Information on Diabetes for Persons With Disabilities Are You at Risk for Diabetes? If you are living with a disability, you know the many ways that having a disability affects your life. Something that you may not know is that living with a disability can put you at risk for developing other conditions, called secondary conditions. -

Promoting Physical Activity and Active Living in Urban Environments

PROMOTING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND ACTIVE LIVING IN URBAN ENVIRONMENTS LIVINGINURBANENVIRONMENTS ANDACTIVE ACTIVITY PHYSICAL PROMOTING The WHO Regional Offi ce for Europe THE SOLID The World Health Organization (WHO) is FACTS a specialized agency of the United Nations created in 1948 with the primary responsibility for international health People’s participation in physical activity is infl uenced by the built, natural matters and public and social environments in which people live as well as by personal health. The WHO Regional Offi ce for factors such as sex, age, ability, time and motivation. The way people Europe is one of six regional offi ces organize cities, design the urban environment and provide access to the throughout the world, each with its own natural environment can be an encouragement or a barrier to physical programme geared to the particular health activity and active living. Other barriers exist in the social environments conditions of the within which people work, learn, play and live. countries it serves. Physical activity is an essential component of any strategy that aims to Member States address the problems of sedentary living and obesity among children and Albania adults. Active living contributes to individual physical and mental health Andorra Armenia but also to social cohesion and community well-being. Opportunities for Austria being physically active are not limited to sports and organized recreation; Azerbaijan Belarus opportunities exist everywhere – where people live and work, in Belgium Bosnia and Herzegovina neighbourhoods and in educational and health establishments. Bulgaria Croatia Cyprus The Healthy Cities and urban governance programme of the WHO Czech Republic Denmark Regional Offi ce for Europe has focused on how local governments can Estonia Finland implement healthy urban planning to generate environments that France promote opportunities for physical activity and active living. -

A Healthy City Is an Active City : a Physical Activity Planning Guide

Abstract This planning guide provides a range of ideas, information and tools for developing a comprehensive plan for creating a healthy, active city by enhancing physical activity in the urban environment. By developing, improving and supporting opportunities in the built and social environments, city leaders and their partners can enable all citizens to be physically active in day-to-day life. Keywords URBAN HEALTH CITIES HEALTH PROMOTION MOTOR ACTIVITY EXERCISE PHYSICAL FITNESS HEALTH POLICY LOCAL GOVERNMENT ISBN 978 92 890 4291 8 Address requests about publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to: Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for permission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). © World Health Organization 2008 All rights reserved. The Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatso- ever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

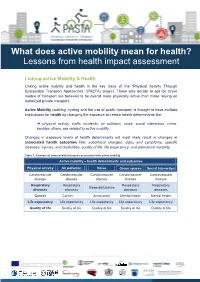

What Does Active Mobility Mean for Health? Lessons from Health Impact Assessment

What does active mobility mean for health? Lessons from health impact assessment Linking active Mobility & Health Linking active mobility and health is the key issue of the “Physical Activity Through Sustainable Transport Approaches” (PASTA) project. Those who decide to opt for active modes of transport are believed to be overall more physically active than those relying on motorized private transport. Active Mobility (walking, cycling and the use of public transport) is thought to have multiple implications for health by changing the exposure to certain health determinants like: physical activity, traffic incidents, air pollution, noise, social interaction, crime, besides others, are related to active mobility. Changes in exposure levels of health determinants will most likely result in changes in associated health outcomes like: subclinical changes, signs and symptoms, specific diseases, injuries, and disabilities, quality of life, life expectancy, and premature mortality. Table 1: Example of some health outcomes associated with active mobility Active mobility – health determinants and outcomes Physical activity Air pollution Noise Green spaces Social interaction Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular disease disease disease disease disease Respiratory Respiratory Respiratory Respiratory Sleep distubance diseases diseases diseases diseases Cancer Cancer Annoyance Mental health Mental health Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research; technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 602624-2. Benefits one translates into benefits for all! The uptake of active mobility impacts not only the health determinants of individual travelers who decide to walk, cycle or use public transport, but also for society as a whole. -

Cycling to Work: Not Only a Utilitarian Movement but Also an Embodiment of Meanings and Experiences That Constitute Crucial

Conclusion This research analysed the different facets of utility cycling in Switzerland, using the example of commuting. We took as our starting point the concept of the cycling system, or velomobility, which underlines the importance of taking into account all elements—not only material and technical but also social, political and symbolic— which influence this practice. From this perspective, we argued that cycling—in terms of volume, frequency, distance, motivation, etc.—depends on the coming together of two potentials. The first of these is motility [11–13] or, more precisely, the indi- viduals’ cycling potential. It is built around access (‘to be able to’ use a means of transport), skills ((‘to know how to’ cycle for utility reasons) and appropriation (‘to want to’ cycle). Individuals’ appropriation of cycling depends on their perception of that mode and of its particularities, which can be interpreted as a confluence of three fundamental dimensions of mobility: movement, meaning and experience in a context of power in regards to the dominant system of automobility [6]. The second of the two potentials is the territory’s hosting potential, or its degree of bikeability, which relates to the spatial context, the available infrastructure and amenities (bicycle urbanism), as well as social and legal norms and rules. In order to identify a large sample of bicycle commuters, we focused on the bike to work scheme, which each year brings together people who commit to cycling to their place of work as often as possible during the months of May and/or June. Nearly 14,000 people completed an online questionnaire addressing the dimensions of velomobility. -

Active Mobility in Singapore 19 Walking and Cycling in the Tropics

Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility 105 © 2014 Centre for Liveable Cities and Urban Land Institute. All rights reserved. Printed on Enviro Wove, an FSC Mix Credit Certified Paper ISBN 978-981-09-2479-9 (print) ISBN 978-981-09-2480-5 (e-book) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Every effort has been made to trace all sources and copyright holders of news articles, figures, and information in this book before publication. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, CLC and ULI will ensure that full credit is given at the earliest opportunity. The e-book can be accessed at http://clc.gov.sg/documents/books/active_ mobility/index.html 4 Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility 5 FOREWORD Cities are for people to live and enjoy. But A bolder plan is to support inter-town cycling. From the pressures on physical infrastructure of the Institute’s global networks to shape some cities are more liveable than others, This will be more challenging. Amsterdam such as transport, housing and public space projects and places in ways that improve the as a result of forward planning and sound took decades to wean off their attachment to through to intangible challenges such as health of people and communities. implementation. private cars and acquire a wonderful culture securing economic competitiveness and of walking and cycling. -

Improving Active Living in Spartanburg County: Report on Progress and Recommendations for the Future

Improving Active Living in Spartanburg County: Report on Progress and Recommendations for the Future Written by: James F. Sallis, Ph.D. Professor of Psychology Director, Active Living Research [email protected] Marc A. Adams, Ph.D., MPH Adjunct Professor of Psychology Post-Doctoral Fellow Ding Ding, MPH Doctoral Student SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Public Health, Health Behavior Research San Diego State University 3900 Fifth Avenue, Suite 310 San Diego, CA 92103 Submitted March 11, 2010 Executive Summary Active Living Research is pleased to present this report as a follow-up to a 2002 white paper. Based partly on the earlier paper, the Mary Black Foundation (MBF) chose Active Living as one of two priority funding areas to improve the health and wellness of people and communities of Spartanburg County, SC. At that time, we believed that the Foundation was forward thinking in their mission and taking a leadership role on a winning health issue. Indeed, years later, the rest of the country has validated this decision. The Convergence Partnership, a consortium of large health-oriented foundations, has launched a similar effort targeting active living and healthy eating. In February 2010, the First Lady and President Obama announced their goal to reverse childhood obesity within a generation by taking a multi-faceted approach that features environment and policy changes. This vision will undoubtedly result in much-needed federal coordination of policies, programs and environmental changes that will complement, but not substitute for, the work of foundations and organizations at the local level. It is now well accepted that healthy environments and policies are needed to support individuals’ healthy choices. -

Active Living Communities

A Primer on Active Living for Government Officials As a government official, you are A Health Crisis uniquely qualified to help residents in America faces a national health crisis of epidemic your jurisdiction become healthier. proportions. Physical inactivity combined with overeating has, in just a few decades, made us a nation Active living is a way of life that integrates physical activity of overweight and out of-shape people. The incidence of into daily routines. The Surgeon General recommends that overweight or obesity among adults increased steadily American adults accumulate at least 30 minutes of from 47 percent in 1976, to 56 percent in 1994, and 64 moderate physical activity each day and that children percent in 2000.3 In 2000, 15.3 percent of children aged 1 engage in at least 60 minutes each day. Individuals may do 6 to 11 years and 15.5 percent of adolescents aged 12 this in a variety of ways, such as walking or bicycling for to 19 years in the United States were overweight, transportation, exercise or pleasure; playing in the park; tripling the numbers from two decades ago.4 working in the yard; taking the stairs; and using recreation facilities. Yet the majority of Americans do not meet the Obesity is a significant risk factor for developing chronic Surgeon General's recommendations. diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. Physical inactivity and obesity now rank second to tobacco use The distance from a person’s home to work and other daily in their contribution to total mortality in the United destinations, the safety of communities and roads for States. -

Smart-Mobility Services for Climate Mitigation in Urban Areas: Case Studies of Baltic Countries and Germany

sustainability Review Smart-Mobility Services for Climate Mitigation in Urban Areas: Case Studies of Baltic Countries and Germany Gabriele Cepeliauskaite 1,*, Benno Keppner 2, Zivile Simkute 1, Zaneta Stasiskiene 1 , Leon Leuser 2, 3 3 3 4 Ieva Kalnina , Nika Kotovica ,Janis¯ Andin, š and Marek Muiste 1 Institute of Environmental Engineering, Kaunas University of Technology, Gedimino 50, 44239 Kaunas, Lithuania; [email protected] (Z.S.); [email protected] (Z.S.) 2 Adelphi, Alt-Moabit 91, 10559 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (B.K.); [email protected] (L.L.) 3 Riga Energy Agency, Maza Jauniela Street 5, LV-1050 Riga, Latvia; [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (N.K.); [email protected] (J.A.) 4 Tartu Regional Energy Agency, Narva mnt 3, 51009 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The transport sector is one of the largest contributors of CO2 emissions and other green- house gases. In order to achieve the Paris goal of decreasing the global average temperature by 2 ◦C, urgent and transformative actions in urban mobility are required. As a sub-domain of the smart-city concept, smart-mobility-solutions integration at the municipal level is thought to have environmental, economic and social benefits, e.g., reducing air pollution in cities, providing new markets for alternative mobility and ensuring universal access to public transportation. Therefore, this article aims to analyze the relevance of smart mobility in creating a cleaner environment and provide strategic and practical examples of smart-mobility services in four European cities: Berlin Citation: Cepeliauskaite, G.; (Germany), Kaunas (Lithuania), Riga (Latvia) and Tartu (Estonia). -

Resource Guide for Healthy Community Planning Framing Questions and Links to Data

WASHINGTON APA’S GAME CHANGING INITIATIVE HEALTH AND PLANNING WORKING GROUP RESOURCE GUIDE FOR HEALTHY COMMUNITY PLANNING FRAMING QUESTIONS AND LINKS TO DATA Contributing Members Alyse S. Nelson, Amalia Leighton, Amy Pow, Andrea Petzel, Elizabeth Chamberlain, Joe Laxson, Julia Walton, Julie Bassuk, Lilith Yanagimachi (Brinkerhoff), Susan Lauinger Cover Graphic and Report Layout Rachel Miller, Kristina Tews Health and Planning Working Group Big Ideas Initiative The Washington American Planning Association’s (APA’s) Game Changing Initiative intends to help planners bring about far-reaching and fundamental change around our state’s most critical challenges. This Initiative is organized around Ten Big Ideas, which include addressing climate change, rebuilding infrastructure, protecting ecosystems, growing economies, and supporting sustainable agriculture. Planning to improve community health is one of the Ten Big Ideas. The Health and Planning Working Group believes planners could benefit from resources to start a conversation with decision-makers, build support, and jump start efforts to incorporate health into planning. To this end, the Working Group has developed a user-friendly resource guide to make it easier for planners to incorporate health considerations into their work. INTRODUCTION The following pages contain a series of framing questions and corresponding links to resources. Each question is from the perspective of a planner wanting to incorporate health into planning. This section also includes a few case study examples and messaging ideas, which outline possible talking points when communicating the importance of health in planning. Framing Questions 1. Why should my community incorporate health into planning? 2 2. How should I begin? What data should I gather and how can I track progress? 3 3. -

Infographic: Walking and Cycling

WALKING AND CYCLING GOOD FOR THE CLIMATE, EVEN BETTER FOR YOUR HEALTH In light of the climate crisis, cities' transport infrastructure and mobility patterns are under scrutiny. BUS This is an excellent opportunity to transform car-focused cities into spaces for people, and improve their health. BENEFITS INCLUDE: A REDUCTION IN... + Death and Diseases Health Costs Social Costs Climate Costs If only 25% of the population For Porto, a shift towards active If 40% less long-duration car trips In Barcelona, Basel, Copenhagen, in EU cities would cycle transportation could lead to were substituted by public transport Paris, Prague and Warsaw an instead of use other modes up to €6.7 billion in health and cycling trips, this would result in increase in bicycle trips to 35% of all of transport, over 10,000 benefits annually, through reductions of 127 cases of diabetes, trips would reduce carbon dioxide premature deaths could reductions in cancer, diabetes, 44 of cardiovascular diseases, 30 of emissions in the six cities by up be avoided each year. heart and cerebrovascular disease. dementia, in the case of i.e. Barcelona. to 26,423 metric tonnes per year. BENEFITS ARE POSSIBLE FOR EACH CITY FOR... PHYSICAL ACTIVITY HEALTHY AIR LESS NOISE CLIMATE ACTION WE CALL ON DECISION-MAKERS TO: Prioritise walking Involve citizens Invest in safe Designate and and cycling in planning decisions cycling routes increase green and and measures public spaces HEAL gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the European Union (EU) and the European Climate Foundation for the production of this publication. The responsibility for the content lies with the authors and the views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the EU institutions and funders.