Social Capital and Health Services Utilization in Msm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Rubber Stamp to a Divided City Council Chicago City Council Report #11 June 12, 2019 – April 24, 2020

From Rubber Stamp to a Divided City Council Chicago City Council Report #11 June 12, 2019 – April 24, 2020 Authored By: Dick Simpson Marco Rosaire Rossi Thomas J. Gradel University of Illinois at Chicago Department of Political Science April 28, 2020 The Chicago Municipal Elections of 2019 sent earthquake-like tremors through the Chicago political landscape. The biggest shock waves caused a major upset in the race for Mayor. Chicago voters rejected Toni Preckwinkle, President of the Cook County Board President and Chair of the Cook County Democratic Party. Instead they overwhelmingly elected former federal prosecutor Lori Lightfoot to be their new Mayor. Lightfoot is a black lesbian woman and was a partner in a major downtown law firm. While Lightfoot had been appointed head of the Police Board, she had never previously run for any political office. More startling was the fact that Lightfoot received 74 % of the vote and won all 50 Chicago's wards. In the same elections, Chicago voters shook up and rearranged the Chicago City Council. seven incumbent Aldermen lost their seats in either the initial or run-off elections. A total of 12 new council members were victorious and were sworn in on May 20, 2019 along with the new Mayor. The new aldermen included five Socialists, five women, three African Americans, five Latinos, two council members who identified as LGBT, and one conservative Democrat who formally identified as an Independent. Before, the victory parties and swearing-in ceremonies were completed, politically interested members of the general public, politicians, and the news media began speculating about how the relationship between the new Mayor and the new city council would play out. -

Gay Marriage Party Ends For

'At Last* On her way to Houston, pop diva Cyndi Lauper has a lot to say. Page 15 voicewww.houstonvoice.com APRIL 23, 2004 THIRTY YEARS OF NEWS FOR YOUR LIFE. AND YOUR STYLE. Gay political kingmaker set to leave Houston Martin's success as a consultant evident in city and state politics By CHRISTOPHER CURTIS Curtis Kiefer and partner Walter Frankel speak with reporters after a Houston’s gay and lesbian com circuit court judge heard arguments last week in a lawsuit filed by gay munity loses a powerful friend and couples and the ACLU charging that banning same-sex marriages is a ally on May 3, when Grant Martin, violation of the Oregon state Constitution. (Photo by Rick Bowmer/AP) who has managed the campaigns of Controller Annise Parker, Council member Ada Edwards, Texas Rep. Garnet Coleman and Sue Lovell, is moving to San Francisco. Back in 1996 it seemed the other Gay marriage way around: Martin had moved to Houston from San Francisco after ending a five-year relationship. Sue Lovell, the former President party ends of the Houston Gay and Lesbian Political Caucus (PAC), remembers first hearing of Martin through her friend, Roberta Achtenberg, the for mer Clinton secretary of Fair for now Housing and Equal Opportunity. “She called me and told me I have a dear friend who is moving back to Ore. judge shuts down weddings, Houston and I want you to take Political consultant Grant Martin, the man behind the campaigns of Controller Annise Parker, good care of him.” but orders licenses recognized Council member Ada Edwards, Texas Rep. -

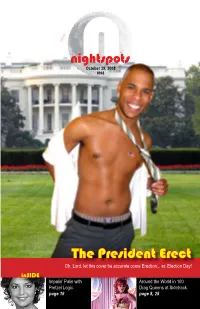

Download PDF Issue

October 29, 2008 #968 The President Erect Oh, Lord, let this cover be accurate come Erection... er, Election Day! inSIDE Impalin’ Palin with Around the World in 100 Pretzel Logic. Drag Queens at Sidetrack. page 16 page 8, 25 out in the stars by Charlene Lichtenstein Get on the campaign trail as little pieces. slid by on oily charm may have this presidential November a second chance to prove gets underway. Lucky Jupiter LEO (JULY 24 - AUG. 23) themselves. By the end of the trines stern Saturn and gives Proud Lions want to slim down month you could be the main us an extra vote that insures for the holidays. Strike while corporate flavor. Let’s hope it our success. So don’t sit on the spirit and flesh are willing. is not roasted turkey. October 29, 2008 your stump. Get Out and At the same time you find #968 vote... twice! ingenious ways to enjoy life CAPRICORN (DEC. 23 - JAN. and lust to the fullest without 20) Pink Caps need a bit of cover ARIES (MARCH 21 - APRIL the extra calories. As you well zest and can put the zip back 20) Your great ideas hit their know, sugar is better spread into their current life course KRIS mark. Say what’s on your than eaten. or find even greener pastures photos by Kirk mind to both superiors and to explore. Viva la difference; subordinates. (Be diplomatic...) VIRGO (AUG. 24 - SEPT. Not only can you discover new INDEX Soon you forget the day to 23) Queer Virgins may have things about yourself, you can THAT GUY day grind and concentrate on trouble focusing on one topic also find some new and excit- 6 the bigger picture —yes, long for an extended period, but ing travel mates. -

Interview with Dawn Clark Netsch # ISL-A-L-2010-013.07 Interview # 7: September 17, 2010 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Dawn Clark Netsch # ISL-A-L-2010-013.07 Interview # 7: September 17, 2010 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Friday, September 17, 2010 in the afternoon. I’m sitting in an office located in the library at Northwestern University Law School with Senator Dawn Clark Netsch. Good afternoon, Senator. Netsch: Good afternoon. (laughs) DePue: You’ve had a busy day already, haven’t you? Netsch: Wow, yes. (laughs) And there’s more to come. DePue: Why don’t you tell us quickly what you just came from? Netsch: It was not a debate, but it was a forum for the two lieutenant governor candidates sponsored by the group that represents or brings together the association for the people who are in the public relations business. -

Youth Count 2.0!

Youth Count 2.0! Full Report of Findings May 13, 2015 Sarah C. Narendorf, PhD, LCSW Diane M. Santa Maria, DrPH, RN Jenna A. Cooper, LMSW i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS YouthCount 2.0! was conducted by the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work in collaboration with the University of Texas School of Nursing and support from the University of Houston-Downtown. The original conceptualization of the study and preliminary study methods were designed under the leadership of Dr. Yoonsook Ha at Boston University with support from Dr. Diane Santa Maria and Dr. Noel Bezette-Flores. The study implementation was led by Dr. Sarah Narendorf and Dr. Diane Santa Maria and coordinated by Jenna Cooper, LMSW. The authors wish to thank the Greater Houston Community Foundation Fund to End Homelessness for their generous support of the project and the Child and Family Innovative Research Center at the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work for additional support. The interest and enthusiasm for YouthCount 2.0! began with the Homeless Youth Network who assisted in funding the initial stages of the project along with The Center for Public Service and Family Strengths at the University of Houston- Downtown.. Throughout the project we received whole-hearted support from service providers across Harris County. Special thanks to Covenant House Texas for making their staff available for outreach and supporting every aspect of the program, the Coalition for the Homeless for technical assistance and help with the HMIS data and to Houston reVisions -

Party Wibh Your Peeps

'. .' ,...-, I ,...-, I - , ,...- I '/ ,- , \ I ' \/ , \ Party wibh your Peeps Easter Sunday April 8.2007.2 - 70m Downtown Houston Fish Plaza, 501 Texas Avenue OJ/Producer Joe Bermudez from Rise in Boston WWW.JOEBERMUDEZ.COM A ~~~ Bunnies on the Bayou 28 HOUSTON, TEXAS PLATINUM SPONSORS MfM Fashion ~ DOUTHIT ol.,a", C!IIOU' GOLD SPONSORS SILVER SPONSORS ~,"o.OS.o" ~ . ~~ I .q~.-","--"-,,-,--, ____- ~ _~. I ~ CAMP BUNNY GOLDEN BUNNY BIG BUNNY Sterling H. Weaver, II, M.D., F.A.C.O.G. Ken Council Scott Bradley Easter Weekend April 5 - 8, 2007 FEATURING c.-.Ii ••••••••.."v••••ParlU •• DJ ROLAND BELMARES DJ ABEL DJALYSON CALAGNA and DJ JAMIE J. SANCHE Tickets and Weekend Passes available at www.J.~.ngleHouston.c ~ ~ ouoSPO"s M AJ 0 R S PO N SO R S .• cenlaur ;;;2J.;:;;:;;,: ~ srON's Gl""",,.G" ==-~hereO ' ~ o I ~~ MALEUWEAR. !)""'~J ARETHA FRANKLIN CONCERT TICKETS WIN IT IETIO SUNIIY EACHWEEI $1.00 WEll and $2.00 DOMESTICS C.nclrt latl: Sat.•IIIr. 21 •• kia TIIlaan lrand Prairie WavneSmlth 1--- --I Wednesdav .1; Starting @ 10p BIG Hln're's 11.llIars DEAL InCaShan. Prizes InIlay each nln" • ~ ~ t ~s. if h ~i Red Nightlife, HZS, LLC 4000 N. Central, Ave., Ste. 1250 Phoenix, AZ 85012' 602-308-8310 Managing Editor Mike Zydzik, Partner [email protected] Editorial Assistant Stacey Jay Cavaliere [email protected] Creative Director Mike Zydzik, Partner [email protected] Contributing Graphic Designers Levi McHale Craig Venezuala Contributing Photographers Carlos Arias David Lewis Irvin Serrano Contributing Writers Hedda Bobbin Tim Burr Stacey Jay Cavaliere The Crimson Imp Michael Knipp Ken Knox David Lewis Tits McGee Noel MikeyRox Richard Gaylord Wood III National Sales Director Chris Smith, Partner 602-308-8310 xl [email protected] Advertising Account Managers Phoenix Gary Guerin 602- 308-831 Ox2 TEXAS Dallas Frank Noel Dominicci Jacob Parrish 214-909-5253 682-472-3185 Houston David Lewis 713-240-5508 Noa Tylo releases sol ohomore album. -

The 2014 Illinois Governor Race: Quinn Vs Rauner John S

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC The imonS Review (Occasional Papers of the Paul Paul Simon Public Policy Institute Simon Public Policy Institute) 1-2015 The 2014 Illinois Governor Race: Quinn vs Rauner John S. Jackson Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ppi_papers Paper #40 of the Simon Review Recommended Citation Jackson, John S., "The 2014 Illinois Governor Race: Quinn vs Rauner" (2015). The Simon Review (Occasional Papers of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute). Paper 40. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ppi_papers/40 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Simon Review (Occasional Papers of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute) by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Simon Review The 2014 Illinois Governor Race: Quinn vs. Rauner By: John S. Jackson Paper #40 January 2015 A Publication of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute Southern Illinois University Carbondale Author’s Note: I want to thank Cary Day, Jacob Trammel and Roy E. Miller for their valuable assistance on this project. THE SIMON REVIEW The Simon Review papers are occasional nonacademic papers of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University Carbondale that examine and explore public policy issues within the scope of the Institute’s mission and in the tradition of the University. The Paul Simon Public Policy Institute acts on significant and controversial issues impacting the region, the state, the nation, and the world. -

Letter Reso 1..3

*LRB10108178ALS53244r* HR0078 LRB101 08178 ALS 53244 r 1 HOUSE RESOLUTION 2 WHEREAS, The members of the Illinois House of 3 Representatives are saddened to learn of the death of Lynda 4 DeLaforgue of Chicago, who passed away on January 12, 2019; and 5 WHEREAS, Lynda DeLaforgue was born in Chicago to James and 6 June DeLaforgue on February 18, 1958; she was raised in 7 Franklin Park; her father was a tuck pointer and a village 8 firefighter, and her mother was employed in the business office 9 of a local paper company; she graduated from Rockford College 10 in 1980, where she majored in theater and was active in local 11 community productions; in 1985, she married Hans Hintzen, and 12 they settled in Chicago's Edgewater neighborhood; they later 13 divorced; and 14 WHEREAS, Lynda DeLaforgue was working as an actress and 15 looking for part-time work when she took a job fundraising for 16 the relatively new Illinois Public Action Council; effective as 17 a door-to-door canvasser and recruiter, she soon became the 18 group's Rockford office manager and helped organize a voter 19 registration drive leading up to the 1984 election; she then 20 became the group's statewide canvass manager and helped set up 21 similar canvass operations in other states; she also took an 22 increasing role in the organization's issue work, especially 23 around health policy and consumer protection; she was HR0078 -2- LRB101 08178 ALS 53244 r 1 simultaneously involved in many progressive political 2 campaigns and helped elect Paul Simon to the U.S. -

7 Arrested at V-Day Marriage Protest

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Feb. 18, 2009 • vol 24 no 21 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com 7 arrested at V-Day marriage protest Condom BY YASMIN NAIR Campaigns When Proposition 8 passed in November 2008, it page 7 prompted a series of actions across the country and legal challenges in California. On March 5, the California Supreme Court will begin to hear arguments against Prop 8. In order to high- light the importance of the upcoming trial, Gay Liberation Network (GLN) and Join the Impact Chicago organized a Valentine’s Day action at the Cook County Marriage License Bureau, 50 W. Washington. This began with a traditional picket outside the building and ended with a sit-in in- side that resulted in the arrest of seven marriage activists. More than 300 people showed up at the protest Viola at 11 a.m. Feb. 14 in downtown Chicago, hold- ing signs and chanting during an initial picket Davis page 15 outside 118 S. Michigan. One man, with a sign that said, “Obama, Don’t 4Get,” said that he was there because “[w]e don’t the same protections that other couples have. The unions that that we have are just as valid as heterosexual unions.” Marriage-equality activists show unity by raising their fists at the Cook County License Bureau Turn to page 6 Feb. 14. Photo by Yasmin nair RuPaul’s amazing Sara Feigenholtz’s John ‘Race’ run for the House O’Hurley page 11 Over the next two weeks, Windy City Times will run interviews with several candidates vying for the Fifth Congressional District. -

2016 Program Book

2016 INDUCTION CEREMONY Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame Gary G. Chichester Mary F. Morten Co-Chairperson Co-Chairperson Israel Wright Executive Director In Partnership with the CITY OF CHICAGO • COMMISSION ON HUMAN RELATIONS Rahm Emanuel Mona Noriega Mayor Chairman and Commissioner COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST Published by Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame 3712 North Broadway, #637 Chicago, Illinois 60613-4235 773-281-5095 [email protected] ©2016 Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame In Memoriam The Reverend Gregory R. Dell Katherine “Kit” Duffy Adrienne J. Goodman Marie J. Kuda Mary D. Powers 2 3 4 CHICAGO LGBT HALL OF FAME The Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame (formerly the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame) is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, its Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (later the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame (changed to the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 2015) in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. Today, after the advisory council’s abolition and in partnership with the City, the Hall of Fame is in the custody of Friends of the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame, an Illinois not- for-profit corporation with a recognized charitable tax-deductible status under Internal Revenue Code section 501(c)(3). -

SHEILA PEPE Invites SONDRA PERRY Put Me Down

3400 MAIN STREET, SUITE 292 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77002 DIVERSEWORKS.ORG PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: --Jennifer Gardner, Deputy Director, DiverseWorks [email protected] / 713.223.8346 SHEILA PEPE invites SONDRA PERRY Put me down Gently: A Cooler Place + I'm Afraid I Can't Do That FRIDAY JUNE 10 6 – 7 pm: Patron and Member Preview 6:30 pm: Artist’s Talk 7 – 9 pm: Public Reception On view: June 11 – August 6, 2016 (Houston, TX, MAY 26, 2016) – DiverseWorks is pleased to announce the opening of SHEILA PEPE invites SONDRA PERRY -- Put me down Gently: A Cooler Place + I'm Afraid I Can't Do That, on view in the gallery at 3400 Main Street, June 11 – August 6. There will be a member’s preview and artist talk from 6 – 7 pm on Friday, June 10 with a public reception from 7 – 9 pm. Admission to DiverseWorks is free of charge Pepe’s exhibition in Houston is a commissioned installation that serves as an open meeting space and platform for several events, including a video installation by current MFAH Core Fellow Sondra Perry. With an interest in carving out space within solo exhibitions for young artists, Pepe invited Perry, working in video and performance, to respond to her augmented reinstallation of Put me down Gently, 2015. Each artist worked autonomously, yet their projects were hinged by shared resources, the color blue and an investment in improvisation within institutional frameworks. The exhibition evolved and two installations emerged – tethered to each other by ongoing conversations on craft, class, race, place and screens of projection. -

HPO Police Officer to Undergo Sex Re-Assignment Surgery

, One of the hottest gay club tours to make a stop in Houston. Page 13 I I -I w ill t M I H 8~ ¥ H J I I As gay men and lesbians celebrate Gay Pride in the shadow of the § US Capitol June 11,the US Environmental Protection Agency is I fending off an attack by conservatives because it recognized June [[ as Gay & Lesbian Pride Month, (Photo by Adam Cuthbert) 813 i .~~ I Transgender HPDofficer Julia Oliver is flanked by local gay attorney Jerry Simoneaux, along with legal partner and attorney Phillys Randolph '"@ EPA under 0 fire Frye, the only openly transgender lawyer in Texas,during a press conference this week, (Photo by Dalton DeHart) I I ::~: for holding HPO police officer to undergo 'I~~: I-~~ , Pride events @ ,J sex re-assignment surgery. .~ Federal worker groups I tional changes had already began F cautious about festivities 24':year veteran police officer said occurring, Oliver had planned to wait I on officially coming out to the Houston i By LOU CHIBBARO JR. ."" .•. department has supported transition Police Department until a recent high- ill snf'f'fI oh:lS" chanced her mind, i The If.S. Environmental Protection Aaencv As gay men and lesbians celebrate Gay Pride in the shadow of the U.S.Capitol June 11,the U.S.Environmental Protection Agency is . fending off an attack by conservatives because it recognized June as Gay& Lesbian Pride Month. (Photo by Adam Cuthbert) Transgender HPD officer Julia Oliver is flanked by local gay attorney Jerry Simoneaux, along with legal partner and attorney Phillys Randolph EPAunder fire Frye, the only openly transgender lawyer in Texas,during a press conference this week.