Indian Muslims and Conceptions of Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30Th Anniversary

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30th Anniversary V. Jayarajan Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture is an institution that was first registered on December 20, 1989 under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, vide No. 406/89. Over the last 16 years, it has passed through various stages of growth, especially in the fields of performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. Since its inception in 1989, Folkland has passed through various phases of growth into a cultural organization with a global presence. As stated above, Folkland has delved deep into the fields of stage performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. It has strived hard and treads the untrodden path with a clear motto of preservation and inculcation of old folk and cultural values in our society. Folkland has a veritable collection of folk songs, folk art forms, riddles, fables, myths, etc. that are on the verge of extinction. This collection has been recorded and archived well for scholastic endeavors and posterity. As such, Folkland defines itself as follows: 1. An international center for folklore and culture. 2. A cultural organization with clearly defined objectives and targets for research and the promotion of folk arts. Folkland has branched out and reached far and wide into almost every nook and corner of the world. The center has been credited with organizing many a festival on folk arts or workshop on folklore, culture, linguistics, etc. -

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in Unani Tibb in India, C. 1890

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in UnaniTibb in India, c. 1890 -1930 Guy Nicolas Anthony Attewell Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London ProQuest Number: 10673235 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673235 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis breaks away from the prevailing notion of unanitibb as a ‘system’ of medicine by drawing attention to some key arenas in which unani practice was reinvented in the early twentieth century. Specialist and non-specialist media have projected unani tibb as a seamless continuation of Galenic and later West Asian ‘Islamic’ elaborations. In this thesis unani Jibb in early twentieth-century India is understood as a loosely conjoined set of healing practices which all drew, to various extents, on the understanding of the body as a site for the interplay of elemental forces, processes and fluids (humours). The thesis shows that in early twentieth-century unani ///)/; the boundaries between humoral, moral, religious and biomedical ideas were porous, fracturing the realities of unani practice beyond interpretations of suffering derived from a solely humoral perspective. -

Rise of Muslim Political Parties

Rise of Muslim Political Parties Abhishek M. Chaudhari Research Fellow Political parties created of, by and for Muslims in India has all the potential to become the defining trend of the current decade. The politics of the last 30 years was defined by the creation of caste-based parties comprising various strands of OBCs and Dalits – which branched out from mainstream political parties in many states. The 21st century may see Muslim parties seeking to discover their own power of agency. The all Muslim political party isn’t a new idea. Indian subcontinent partitioned on the same plank. The Jinnah led Muslim League wanted separate nation for Muslims and they had it. After independence, the Muslim League wasrenamed as the Indian Union Muslim League.Its objective of becomingan all India party never receivedcountry-wide acceptance and it managedto exist only in the state of Kerala. In 1989, politician Syed Shahabuddinattempted to form the Insaf Party withthe same aims. His idea was to mobilise Muslims, other religious minorities,SCs, STs and the backwardclasses under oneoverarching umbrella. But it ended in failure. Post 2000, there is strong debate in the community about the political formations for Muslims. A section of Muslim elites favoured a formation of political party catering to ‘Muslim cause’ at the regional level. This is contrary to earlier attempts to have such formation at a pan-national level.Others section is still sceptical about such ventures. It is of the opinion that Muslimsneed not form any political party fortheir “own”, as regional parties are pushing their case. Amidst such political churning in the community, some political formation took birth at regional level. -

Volume-13-Skipper-1568-Songs.Pdf

HINDI 1568 Song No. Song Name Singer Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14040 Aa Hosh Mein Sun Suresh Wadkar Vidhaata Volume-9 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 13617 Aadmi Zindagi Mohd Aziz Vishwatma Volume-9 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 14132 Aah Ko Chajiye Jagjit Singh Mirza Ghalib Volume-9 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 13620 Aaina Mujhse Meri Talat Aziz Suraj Sanim Daddy Volume-9 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

Written Testimony of Musaddique Thange Communications Director Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC)

Written Testimony of Musaddique Thange Communications Director Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) for ‘Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India’ by Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission June 7, 2016 1334 Longworth House Office Building Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission - June 7, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction Religious violence, hate speeches and other forms of persecution The Hindu Nationalist Agenda Religious Violence Hate / Provocative speeches Cow related violence - killing humans to protect cows Ghar Wapsi and the Business of Forced and Fraudulent Conversions Love Jihad Counter-terror Scapegoating of Impoverished Muslim Youth Curbs on Religious Freedoms of Minorities Caste based reservation only for Hindus; Muslims and Christians excluded No distinct identity for Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains Anti-Conversion Laws and the Hindu Nationalist Agenda A Broken and Paralyzed Judiciary Myth of a functioning judiciary Frivolous cases and abuse of judicial process Corruption in the judiciary Destruction of evidence Lack of constitutional protections Recommendations US India Strategic Dialogue Human Rights Workers’ Exchange Program USCIRF’s Assessment of Religious Freedom in India Conclusion Appendix A: Hate / Provocative speeches MP Yogi Adityanath (BJP) MP Sakshi Maharaj (BJP) Sadhvi Prachi Arya Sadhvi Deva Thakur Baba Ramdev MP Sanjay Raut (Shiv Sena) Written Testimony - Musaddique Thange (IAMC) 1 / 26 Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission - June 7, 2016 Introduction India is a multi-religious, multicultural, secular nation of nearly 1.25 billion people, with a long tradition of pluralism. It’s constitution guarantees equality before the law, and gives its citizens the right to profess, practice and propagate their religion. -

Politicizing Islam: State, Gender, Class, and Piety in France and India

Politicizing Islam: State, gender, class, and piety in France and India By Zehra Fareen Parvez A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Burawoy, Chair Professor Raka Ray Professor Cihan Tuğal Professor Loïc Wacquant Professor Kiren Aziz-Chaudhry Fall 2011 Abstract Politicizing Islam: State, gender, class, and piety in France and India by Zehra Fareen Parvez Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Burawoy, Chair This dissertation is a comparative ethnographic study of Islamic revival movements in Lyon, France, and Hyderabad, India. It introduces the importance of class and the state in shaping piety and its politicization. The project challenges the common conflation of piety and politics and thus, the tendency to homogenize “political Islam” even in the context of secular states. It shows how there have been convergent forms of piety and specifically gendered practices across the two cities—but divergent Muslim class relations and in turn, forms of politics. I present four types of movements. In Hyderabad, a Muslim middle-class redistributive politics directed at the state is based on patronizing and politicizing the subaltern masses. Paternalistic philanthropy has facilitated community politics in the slums that are building civil societies and Muslim women’s participation. In Lyon, a middle-class recognition politics invites and opposes the state but is estranged from sectarian Muslims in the working-class urban peripheries. Salafist women, especially, have withdrawn into a form of antipolitics, as their religious practices have become further targeted by the state. -

M/S. SKYANSH FILMS PRODUCTION 25073

M/s. SKYANSH FILMS PRODUCTION M/s. SURYA STUTI ENTERTAINMENT 25073 - 01/03/2016 25081 - 01/03/2016 406, 407, 408, Sanmahu Complex, 4th Floor, Opp. Poona Club, House No.227, Village Bhargwan, Shahjahanpur, Bund Garden Road, Pune, 242 001 U.P. 411 001 Maharashtra SURYA KANT VERMA SURESH KESHAVRAO YADAV 9892983731 9822619772 M/s. B V M FILMS M/s. YADUVANSHI FILMS PRODUCTION HOUSE 25074 - 01/03/2016 25082 - 01/03/2016 L 503, Anand Vihar CHS, Opp. Windermere, Oshiwara, Andheri 5/131, Jankipuram, Sector-H, Lucknow, (W), Mumbai, 226 021 U.P. 400 053 Maharashtra RAMESH KUMAR YADAV MANOJ BINDAL, SANTOSH BINDAL, OM PRAKASH BINDAL 9839384024 9811045118 M/s. SHIVAADYA FILM PRODUCTION PVT. LTD. M/s. MAHAKALI ENTERTAINMENT WORLD 25075 - 01/03/2016 25083 - 01/03/2016 L 14/516, Bldg. No.1, 5th Floor, Kamdhenu Apna Ghar Unit Naya Salempur-1, Salempur, Tehsil: Lakhimpur, Dist: Kheri, No.14, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri (W), Mumbai, 262 701 U.P. 400 053 Maharashtra AJAY RASTOGI SANGITA ANAND, SABITA MUNKA 9598979590 7710891401 M/s. ADINATH ENTERTAINMENT & FILM PRODUCTION M/s. FAIZAN-A-RAZA FILM PRODUCTION 25076 - 01/03/2016 25084 - 01/03/2016 L 9/A, Saryu Vihar, Basant Vihar, Kamla Nagar, Agra, 35, Hivet Road, Aminabad, Tehsil & Dist: Lucknow, 282 002 U.P. 226 018 U.P. VIMAL KUMAR JAIN ABDUL AZIZ SIDDIQUE 8445611111 9451503544, 9335218406 M/s. SHIV OM PRODUCTION M/s. SHREE SAI FILMS ENTERTAINMENT HOUSE 25077 - 01/03/2016 25085 - 01/03/2016 Kalpataru Aura, Building No.Onyx 3G,Flat No.111, L.B.S. Marg, Plot No.21/A, Netaji Nagar, Old Pardi Naka, Near Prathmesh Opp. -

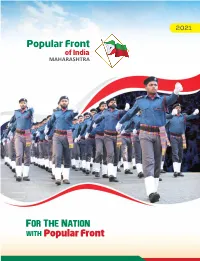

2021 Chairman’S Message

2021 Chairman’s Message For a diverse nation like India, to thrive and progress the most essential values required are freedom, justice, and equality before the law, and tolerance towards those who are dierent from us in terms of faith, culture, language, or customs. Immediately after we were relieved of the brunt of colonial occupation, our ancestors envisioned making our country a secular, democratic republic with a constitution that guarantees fundamental rights and equality before the law regardless of all these dierences. Though we were a struggling democracy all through, we had the hope that striving together, we could create a bright future. However, it is no secret anymore that we have long abandoned what our ancestors had envisaged and have embarked on a journey in the opposite direction. The idea of O. M. A. Salam hatred that designated fellow citizens as aliens or Chairman, Popular Front Of India enemies was not something unexpected or instantaneous. But whoever preached such ideas were kept at bay in the early days of our republic. Later on, in their pathetic attempt to preserve their power and privileges, the so-called secular leaders who ruled us colluded with the right-wing Hindutva forces and allowed them to make inroads into the system. There were times, as a citizen, you could fearlessly criticize the government, which now gets termed as ‘anti-national’. You go to jail for the jokes you cracked and even for the ones you didn’t. Laws hang over our heads that say people might lose their citizenship on account of their religion. -

In This Interview: Adam Tells Resurgence Azzam Al-Amriki June 25, 2015

In this interview: Adam tells Resurgence Azzam al-Amriki June 25, 2015 [Please note: Images may have been removed from this document. Page numbers may have been added.] Targeting India will remain one of the Mujahideen’s priorities as long as it pursues its antagonistic policies and continues to engage in and condone the persecution, murder and rape of Muslims and occupation of their land The way forward for our persecuted brothers in Bangladesh is Da’wah and Jihad The Pakistani regime bears responsibility for the toppling of the Islamic Emirate and the occupation of Afghanistan, and its crimes are continuing unabated While in Pakistan, I and my brothers were blessed with numerous supporters who sheltered and took care of us despite the risk The Americans and their Pakistani agents almost captured me in Karachi on at least two occasions Shaykh Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi had the qualities of a great leader and a smile which could illuminate a city The Americans came close to martyring Shaykh Abu Mus’ab (may Allah have mercy on him) in Afghanistan, but Allah preserved him until he became America’s number one enemy in Iraq Shaykh Abu Mus’ab was a champion of unity who fought for the Ummah, and he should not be held responsible for the deviation today of some people who falsely claim to follow him and his methodology A Muslim’s blood is sacred, more sacred even than the Ka’aba, and spilling it without right is not only an act of oppression, it is the greatest sin after Kufr and Shirk The blessed raids of September 11th rubbed America’s nose in -

Submitted By

EXTREMISM-TERRORISM IN THE NAME OF ISLAM IN PAKISTAN: CAUSES & COUNTERSTRATEGY Submitted by: RAZA RAHMAN KHAN QAZI PhD SCHOLAR DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (DECEMBER 2012) 1 EXTREMISM-TERRORISM IN THE NAME OF ISLAM IN PAKISTAN: CAUSES & COUNTERSTRATEGY Submitted BY RAZA RAHMAN KHAN QAZI PhD SCHOLAR Supervised By PROF. DR. IJAZ KHAN A dissertation submitted to the DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR, PESHAWAR In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN International Relations December 2012 2 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation is the outcome of my individual research and it has not been submitted to any other university for the grant of a degree. Raza Rahman khan Qazi 3 APPROVAL CERTIFICATE Pakhtuns and the War on Terror: A Cultural Perspective Dissertation Presented By RAZA RAHMAN KHAN QAZI To the Department of International Relations University of Peshawar In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. in International Relations December 2012 We, the undersigned have examined the thesis entitled “Extremism-Terrorism in the Name of Islam in Pakistan: Causes & Counterstrategy” written by Raza Rahman Khan Qazi, a Ph.D. Scholar at the Department of International Relations, University of Peshawar and do hereby approve it for the award of Ph.D. Degree. APPROVED BY: Supervisor: ___________________________________ PROF. DR. IJAZ KHAN Professor Department of International Relations University of Peshawar External Examiner: ………………………………………………. Dean: ________________________________________ PROF. DR. NAEEM-UR-REHMAN KHATTAK Faculty of Social sciences University of Peshawar Chairman: _______________________________________ PROF.DR. ADNAN SARWAR KHAN Department of International Relations University of Peshawar 4 INTRODUCTION The World in the post Cold War period and particularly since the turn of the 21st Century has been experiencing peculiar multidimensional problems that have seriously threatened human and state security. -

Iranian Revolution, Khomeini and the Shi'ite Faith

Iranian Revolution, Khomeini and The Shi’ite Faith By Maulana Mohammad Manzoor Nomani Source: http://www.tauheed-sunnat.com/sunnat/content/sect- deviation-from-straight-path-of-islam Table of contents • 01. Forward • 02. Preface • 03. The nature of Iranian Revolution and its Foundation • 04. Khomeini in the light of his own books • 05. Holy Companions ( First Two Caliphs ) • 06. Kashf-ul-Israr • 07. Shia'ite Faith defined • 08. Isna-e-Ashariyya and the Doctrine of Imamate • 09. The Quran, The Imamate and the Imams Shia'ite View point • 10. Like the apostles, the Imams, too were Nominated by God • 11. The Absent Imam • 12. The incident of Ghadir-e-Khum and thereafter • 13. Some other views and precepts about Hazrat Abu Bakr (r.a) and Hazrat Omar (r.a) Satan was the first to pledge fealty to Abu Bakr (r.a) 01. Forward Submitted by admin on Sat, 03/07/2009 - 02:17 In the Name of God, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful, the One and Unique. All praise to God and salutations and blessing upon His Prophet (s.a.w.w). What was the first and exemplary period of Islam like? What were the practical results of the training and guidance imparted and bestowed by the greatest and the last Prophet of God? What was the life and character of the people who had received guidance and instruction directly at his hands ? Was it, in any way, different from that of the founders of national, racial or family kingdom, sand of the seekers of power and authority? What was the Prophet’s conduct in relation to his family and what was the attitude of the family