Invasive Plants Field and Reference Guide: an Ecological Perspective of Plant Invaders of Forests and Woodlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oriental Bittersweet

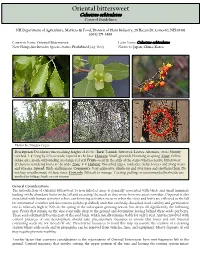

Oriental Bittersweet Department of Environmental Protection Environmental and Geographic Information Center 79 Elm St., Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 424-3540 Invasive Plant Information Sheet Asiatic Bittersweet, Oriental Bittersweet Celastrus orbiculatus Staff Tree Family (Celastraceae) Ecological Impact: Asiatic bittersweet is a rapidly spreading deciduous vine that threatens all vegetation in open and forested areas. It overtops other species and forms dense stands that shade out native vegetation. Trees and shrubs can be strangled by twining stems that twist around and eventually constrict the flow of plant fluids. Trees can be girdled and weighed down by vines in the canopies, making them more susceptible to damage by wind, snow, and ice storms. There is evidence that Asiatic bittersweet can hybridize with American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens), which occurs in similar habitats. Hybridization will destroy the genetic integrity of the native species. Control Methods: The most effective control method for Asiatic Bittersweet is to prevent establishment by annually monitoring for and removing small plants. Eradication of established plants is difficult due to the persistent seed bank in the soil. Larger plants are best controlled by cutting combined with herbicide treatment. Mechanical Control: Light infestations of a few small plants can be controlled by mowing or cutting vines and hand pulling roots. Weekly mowing can eradicate plants, but less frequent mowing ( 2-3 times per year) will only stimulate root suckering. Cutting and uprooting plants is best done before fruiting. Vines with fruits should be bagged and disposed of in the trash to prevent seed dispersal. Heavy infestations can be controlled by cutting vines and immediately treating cut stems with herbicide. -

Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region

$10 $10 PB1785 PB1785 Invasive Weeds Invasive Weeds of the of the Appalachian Appalachian Region Region i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments……………………………………...i How to use this guide…………………………………ii IPM decision aid………………………………………..1 Invasive weeds Grasses …………………………………………..5 Broadleaves…………………………………….18 Vines………………………………………………35 Shrubs/trees……………………………………48 Parasitic plants………………………………..70 Herbicide chart………………………………………….72 Bibliography……………………………………………..73 Index………………………………………………………..76 AUTHORS Rebecca M. Koepke-Hill, Extension Assistant, The University of Tennessee Gregory R. Armel, Assistant Professor, Extension Specialist for Invasive Weeds, The University of Tennessee Robert J. Richardson, Assistant Professor and Extension Weed Specialist, North Caro- lina State University G. Neil Rhodes, Jr., Professor and Extension Weed Specialist, The University of Ten- nessee ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank all the individuals and organizations who have contributed their time, advice, financial support, and photos to the crea- tion of this guide. We would like to specifically thank the USDA, CSREES, and The Southern Region IPM Center for their extensive support of this pro- ject. COVER PHOTO CREDITS ii 1. Wavyleaf basketgrass - Geoffery Mason 2. Bamboo - Shawn Askew 3. Giant hogweed - Antonio DiTommaso 4. Japanese barberry - Leslie Merhoff 5. Mimosa - Becky Koepke-Hill 6. Periwinkle - Dan Tenaglia 7. Porcelainberry - Randy Prostak 8. Cogongrass - James Miller 9. Kudzu - Shawn Askew Photo credit note: Numbers in parenthesis following photo captions refer to the num- bered photographer list on the back cover. HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE Tabs: Blank tabs can be found at the top of each page. These can be custom- ized with pen or marker to best suit your method of organization. Examples: Infestation present On bordering land No concern Uncontrolled Treatment initiated Controlled Large infestation Medium infestation Small infestation Control Methods: Each mechanical control method is represented by an icon. -

Vanduzeea Arquata and Enchenopa Binotata Discrimination of Whole Twigs, Leaf Extracts and Sap Exndates

Host-selection behavior of nymphs of Vanduzeea arquata and Enchenopa binotata Discrimination of whole twigs, leaf extracts and sap exndates Agnes Kiss Division of Biological Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI48109; Present address: Agricultural Production Division, Room 413 SA-18, Office of Agriculture, Bureau for Science and Technology, Agency for International Development, Washington, DC 20523, USA Keywords: host-discrimination, Homoptera, Membracidae, Vanduzeea arquata, Enchenopa binotata, secondary compounds, alkaloids, phloem sap, hop-tree Ptelea trifoliata Abstract The host-discrimination behavior of two species of phloem-feeding membracid nymphs was examined through pair-wise choice experiments using whole twigs, leaf extracts and sap exudates. Both species have restricted host ranges in the field: Vanduzeea arquata is monophagous, while Enchenopa binotata may best be considered narrowly oligophagous in that it represents a complex of sympatric, reproductively isolated populations each associated with a different species or genus of plants. Nymphs of both species settled preferentially on twigs of their respective host plants but those of V. arquata showed absolute discrimination while those orE. binotata selected the alternative twigs a small percentage of the time. Vanduzeea arquata nymphs also showed a greater sensitivity to plant extracts, as a larger proportion of their responses, both positive and negative, were significant. Leaf extracts of all plants tested discouraged ingestion but not probing, and most nymphs exhibited a positive probing response to the extracts of their respective hosts. Only the sap exudates of the hop-tree (Ptelea trifoliata) inhibited ingestion. Enchenopa binotata nymphs from the population associated with the hop-tree also showed a negative response to these extracts but only at a higher concentration. -

Oriental Bittersweet Orientalcelastrus Bittersweet Orbiculatus Controlcontrol Guidelinesguidelines

Oriental bittersweet OrientalCelastrus bittersweet orbiculatus ControlControl GuidelinesGuidelines NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Oriental Bittersweet Latin Name: Celastrus orbiculatus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan, China, Korea Photos by: Douglas Cygan Description: Deciduous vine reaching heights of 40-60'. Bark: Tannish, furrowed. Leaves: Alternate, ovate, bluntly toothed, 3-4'' long by 2/3’s as wide, tapered at the base. Flowers: Small, greenish, blooming in spring. Fruit: Yellow dehiscent capsule surrounding an orange-red aril. Fruits occur in the axils of the stems whereas native bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) fruits at the ends. Zone: 4-8. Habitat: Disturbed edges, roadsides, fields, forests and along rivers and streams. Spread: Birds and humans. Comments: Very aggressive, climbs up and over trees and smothers them. Do not buy wreaths made of these vines. Controls: Difficult to manage. Cutting, pulling, or recommended herbicide use applied to foliage, bark, or cut-stump. General Considerations The introduction of Oriental bittersweet to non infested areas is generally associated with birds and small mammals feeding on the abundant fruits in the fall and excreting the seeds as they move from one area to another. Dispersal is also associated with human activities where earth moving activities occur or when the vines and fruits are collected in the fall for ornamental wreathes and decorations (which is prohibited) and then carelessly discarded. Seed viability and germination rate is relatively high at 90% in the spring of the subsequent growing season, but drops off significantly the following year. -

Porcelain Berry

FACT SHEET: PORCELAIN-BERRY Porcelain-berry Ampelopsis brevipedunculata (Maxim.) Trautv. Grape family (Vitaceae) NATIVE RANGE Northeast Asia - China, Korea, Japan, and Russian Far East DESCRIPTION Porcelain-berry is a deciduous, woody, perennial vine. It twines with the help of non-adhesive tendrils that occur opposite the leaves and closely resembles native grapes in the genus Vitis. The stem pith of porcelain-berry is white (grape is brown) and continuous across the nodes (grape is not), the bark has lenticels (grape does not), and the bark does not peel (grape bark peels or shreds). The Ieaves are alternate, broadly ovate with a heart-shaped base, palmately 3-5 lobed or more deeply dissected, and have coarsely toothed margins. The inconspicuous, greenish-white flowers with "free" petals occur in cymes opposite the leaves from June through August (in contrast to grape species that have flowers with petals that touch at tips and occur in panicles. The fruits appear in September-October and are colorful, changing from pale lilac, to green, to a bright blue. Porcelain-berry is often confused with species of grape (Vitis) and may be confused with several native species of Ampelopsis -- Ampelopsis arborea and Ampelopsis cordata. ECOLOGICAL THREAT Porcelain-berry is a vigorous invader of open and wooded habitats. It grows and spreads quickly in areas with high to moderate light. As it spreads, it climbs over shrubs and other vegetation, shading out native plants and consuming habitat. DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES Porcelain-berry is found from New England to North Carolina and west to Michigan (USDA Plants) and is reported to be invasive in twelve states in the Northeast: Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington D.C., West Virginia, and Wisconsin. -

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

Emerging Invasion Threat of the Liana Celastrus Orbiculatus

A peer-reviewed open-access journal NeoBiota 56: 1–25 (2020)Emerging invasion threat of the liana Celastrus orbiculatus in Europe 1 doi: 10.3897/neobiota.56.34261 RESEARCH ARTICLE NeoBiota http://neobiota.pensoft.net Advancing research on alien species and biological invasions Emerging invasion threat of the liana Celastrus orbiculatus (Celastraceae) in Europe Zigmantas Gudžinskas1, Lukas Petrulaitis1, Egidijus Žalneravičius1 1 Nature Research Centre, Institute of Botany, Žaliųjų Ežerų Str. 49, Vilnius LT-12200, Lithuania Corresponding author: Zigmantas Gudžinskas ([email protected]) Academic editor: Franz Essl | Received 4 March 2019 | Accepted 12 March 2020 | Published 10 April 2020 Citation: Gudžinskas Z, Petrulaitis L, Žalneravičius E (2020) Emerging invasion threat of the liana Celastrus orbiculatus (Celastraceae) in Europe. NeoBiota 56: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.56.34261 Abstract The woody vine Celastrus orbiculatus (Celastraceae), Oriental bittersweet, is an alien species that recently has been found to be spreading in Europe. Many aspects of its biology and ecology are still obscure. This study evaluates the distribution and habitats, as well as size and age of stands of C. orbiculatus in Lithuania. We investigated whether meteorological factors affect radial stem increments and determined seedling recruit- ment in order to judge the plant’s potential for further spread in Europe. We studied the flower gender of C. orbiculatus in four populations in Lithuania and found that all sampled individuals were monoecious, although with dominant either functionally female or male flowers. Dendrochronological methods enabled us to reveal the approximate time of the first establishment of populations of C. orbiculatus in Lithuania. -

Rare Plants of Louisiana

Rare Plants of Louisiana Agalinis filicaulis - purple false-foxglove Figwort Family (Scrophulariaceae) Rarity Rank: S2/G3G4 Range: AL, FL, LA, MS Recognition: Photo by John Hays • Short annual, 10 to 50 cm tall, with stems finely wiry, spindly • Stems simple to few-branched • Leaves opposite, scale-like, about 1mm long, barely perceptible to the unaided eye • Flowers few in number, mostly born singly or in pairs from the highest node of a branchlet • Pedicels filiform, 5 to 10 mm long, subtending bracts minute • Calyx 2 mm long, lobes short-deltoid, with broad shallow sinuses between lobes • Corolla lavender-pink, without lines or spots within, 10 to 13 mm long, exterior glabrous • Capsule globe-like, nearly half exerted from calyx Flowering Time: September to November Light Requirement: Full sun to partial shade Wetland Indicator Status: FAC – similar likelihood of occurring in both wetlands and non-wetlands Habitat: Wet longleaf pine flatwoods savannahs and hillside seepage bogs. Threats: • Conversion of habitat to pine plantations (bedding, dense tree spacing, etc.) • Residential and commercial development • Fire exclusion, allowing invasion of habitat by woody species • Hydrologic alteration directly (e.g. ditching) and indirectly (fire suppression allowing higher tree density and more large-diameter trees) Beneficial Management Practices: • Thinning (during very dry periods), targeting off-site species such as loblolly and slash pines for removal • Prescribed burning, establishing a regime consisting of mostly growing season (May-June) burns Rare Plants of Louisiana LA River Basins: Pearl, Pontchartrain, Mermentau, Calcasieu, Sabine Side view of flower. Photo by John Hays References: Godfrey, R. K. and J. W. Wooten. -

Landscape Vines for Southern Arizona Peter L

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AZ1606 October 2013 LANDSCAPE VINES FOR SOUTHERN ARIZONA Peter L. Warren The reasons for using vines in the landscape are many and be tied with plastic tape or plastic covered wire. For heavy vines, varied. First of all, southern Arizona’s bright sunshine and use galvanized wire run through a short section of garden hose warm temperatures make them a practical means of climate to protect the stem. control. Climbing over an arbor, vines give quick shade for If a vine is to be grown against a wall that may someday need patios and other outdoor living spaces. Planted beside a house painting or repairs, the vine should be trained on a hinged trellis. wall or window, vines offer a curtain of greenery, keeping Secure the trellis at the top so that it can be detached and laid temperatures cooler inside. In exposed situations vines provide down and then tilted back into place after the work is completed. wind protection and reduce dust, sun glare, and reflected heat. Leave a space of several inches between the trellis and the wall. Vines add a vertical dimension to the desert landscape that is difficult to achieve with any other kind of plant. Vines can Self-climbing Vines – Masonry serve as a narrow space divider, a barrier, or a privacy screen. Some vines attach themselves to rough surfaces such as brick, Some vines also make good ground covers for steep banks, concrete, and stone by means of aerial rootlets or tendrils tipped driveway cuts, and planting beds too narrow for shrubs. -

Invasive Plants and the Green Industry

42 Harrington et al.: Invasive Plants and the Green Industry INVASIVE PLANTS AND THE GREEN INDUSTRY By Robin A. Harrington1, Ronald Kujawski2, and H. Dennis P. Ryan3 Abstract. There are many motivations for introducing plant offices were recommending the planting of introduced species to areas outside their native range. Non-native species, such as autumn olive (Elaegnus umbellata) and plants can provide food, medicine, shelter, and ecosystem multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), for wildlife food and cover. services, as well as aesthetic value. However, some species, Despite the many benefits provided by introduced species, such as Norway maple (Acer platanoides), Japanese barberry there has been growing concern recently among land (Berberis thunbergii), and Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus managers regarding the negative impacts when introduced orbiculatus), have escaped from cultivation, with severe species escape cultivation and become invasive in local ecological and economic consequences. The approval of a habitats. Invasive plant species pose a major threat to National Invasive Species Management Plan in June 2001 biodiversity, habitat quality, and ecosystem function. Invasive has major implications for future plant introductions and plants can also have devastating economic impacts, through has generated concern in the green industry. There is loss of revenue (reduced agricultural and silvicultural general agreement among plant professionals regarding (1) production in the presence of invasive species) and the high a need for education of industry people and client groups costs associated with control programs. The magnitude of on the issue of invasive species, (2) minimizing economic these impacts resulted in Executive Order 13112, issued by disruption to the nursery industry, and (3) requirements for President Clinton on February 3, 1999, directing all federal objective data to support listing of species as invasive. -

![Fifay 15, 1884] NATURE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2572/fifay-15-1884-nature-992572.webp)

Fifay 15, 1884] NATURE

fifay 15, 1884] NATURE the position of some of the Cretaceous deposits and the marked Piedmont. By t heir means great piles of broken rock must h~ve mineral differences between these and the Jurassic seem to indi been transported into the lowlands ; hut did they greatly modify cate disturbances dnring some part of the ;-.:- eocomian, but I am the peaks, deepen the v:1lleys, or excavate the lake basms ? My not aware of any marked trace of these over the central and reply would be, '' T o no very material extent. " I r egard (he western areas. The mountain-making of th e existing Alps elates o-Jacier as the fil e rather than as the clusel of nature. The Alpme from the later part of the Eocene. Beds of about the age of our Jakes appear to be more easily explained-as the Dead Sea can Bracklesham series now cap such summits as the Diablerets, or only be explained-as the result of subsidence along zones r<;mghly help to form the mountain masses near the T iid i, rising in the parallel with the Alpine ranges, athwart the general d1 rectt0ns of Bifertenstock to a height of rr, 300 feet above the sea. Still valleys which already existed and had been in the main com there are signs that the sea was then shallowing a nd the epoch pleted in pre-Glacial times. To produce these lake basins we of earth movements commencing. The Eocene deposits of Swit should require earth movements o n n o greater scale t han have cerlancl include terrestrial and fluviatile as well as marine taken place in our own country since the furthermost extension remains. -

Invasive Plants Common in Connecticut

Invasive Plants Common in Connecticut Invasive Plants Common in Connecticut Norway Maple Scientific Name: Acer platanoides L. Origin: Europe & Asia Ecological Threat: Forms monotypic populations by dis- placing native trees, shrubs, and herbaceous understory plants. Once established, it creates a canopy of dense shade that prevents regeneration of native seedlings. Description/Biology: Plant: broad deciduous tree up to 90 ft. in height with broadly-rounded crown; bark is smooth at first but becomes black, ridged and furrowed with age. Leaves: paired, deciduous, dark green, pal- mate (like a hand), broader across than from base to tip, marginal teeth with long hair-like tips. Flowers, fruits and seeds: flowers in spring, bright yellow-green; fruits mature during summer into paired winged “samaras” joined broadly at nearly 180° angle; milky sap will ooze from cut veins or petiole. Similar Species: Other maples including sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and red maple (Acer rubrum). Distin- guish Norway by milky white sap, broad leaves, hair-like leaf tips, samara wings straight out, yellow fall foliage. Native Alternatives: Native maples like sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and red maple (Acer rubrum) Norway Maple Scientific Name: Acer platanoides L. Origin: Europe & Asia Ecological Threat: Forms monotypic populations by dis- placing native trees, shrubs, and herbaceous understory plants. Once established, it creates a canopy of dense shade that prevents regeneration of native seedlings. Description/Biology: Plant: broad deciduous tree up to 90 ft. in height with broadly-rounded crown; bark is smooth at first but becomes black, ridged and furrowed with age. Leaves: paired, deciduous, dark green, pal- mate (like a hand), broader across than from base to tip, marginal teeth with long hair-like tips.