Mehrabad Nawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pashtunistan: Pakistan's Shifting Strategy

AFGHANISTAN PAKISTAN PASHTUN ETHNIC GROUP PASHTUNISTAN: P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER May 2012 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? P ASHTUNISTAN : P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? The Pashtun tribes have yearned for a “tribal homeland” in a manner much like the Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. And as in those coun- tries, the creation of a new national entity would have a destabilizing impact on the countries from which territory would be drawn. In the case of Pashtunistan, the previous Afghan governments have used this desire for a national homeland as a political instrument against Pakistan. Here again, a border drawn by colonial authorities – the Durand Line – divided the world’s largest tribe, the Pashtuns, into two the complexity of separate nation-states, Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they compete with other ethnic groups for primacy. Afghanistan’s governments have not recog- nized the incorporation of many Pashtun areas into Pakistan, particularly Waziristan, and only Pakistan originally stood to lose territory through the creation of the new entity, Pashtunistan. This is the foundation of Pakistan’s policies toward Afghanistan and the reason Pakistan’s politicians and PASHTUNISTAN military developed a strategy intended to split the Pashtuns into opposing groups and have maintained this approach to the Pashtunistan problem for decades. Pakistan’s Pashtuns may be attempting to maneuver the whole country in an entirely new direction and in the process gain primacy within the country’s most powerful constituency, the military. -

People of Ghazni

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs/ Province: Zabul April 13, 2009 Governor: Mohammad Ashraf Nasseri Provincial Police Chief: Colonel Mohammed Yaqoub Population Estimate: Urban: 9,200 Rural: 239,9001 249,100 Area in Square Kilometers: 17,343 Capital: Qalat (formerly known as Qalat-i Ghilzai) Names of Districts: Arghandab, Baghar, Day Chopan, Jaldak, Kaker, Mizan, Now Bahar, Qalat, Shah Joy, Shamulza’i, Shinkay Composition of Population: Ethnic Groups: Religions: Tribal Groups: Tokhi & Hotaki Majority Pashtun Predominately Sunni Ghilzais, Noorzai &Panjpai Islam Durranis Occupation of Population Major: Agriculture (including opium), labor, Minor: Trade, manufacturing, animal husbandry smuggling Crops/Farming/ Poppy, wheat, maize, barley, almonds, Sheep, goat, cow, camel, donkey Livestock:2 grapes, apricots, potato, watermelon, cumin Language: Overwhelmingly Pashtu, although some Dari can be found, mostly as a second language Literacy Rate Total: 1% (1% male, a few younger females)3 Number of Educational Primary & Secondary: 168 (98% all Colleges/Universities: None, although Institutions: 80 male) 35272 student (99% male), some training centers do exist for 866 teachers (97% male) vocational skills Number of Security Incidents, January: 3 May: 6 September: 7 2007:774 February: 4 June: 8 October: 7 March: 3 July: 8 November: 10 April: 11 August: 5 December: 5 Poppy (Opium) Cultivation: 2006: 3,210ha 2007: 1,611ha NGOs Active in Province: Ibn Sina, Vara, ADA, Red Crescent, CADG Total PRT Projects: 40 Other Aid Projects: 573 Planned Cost: $8,283,665 Planned Cost: $19,983,250 Total Spent: $2,997,860 Total Spent: $1,880,920 Transportation: 1 Airstrip in Primary Roads: The ring road from Ghazni to Kandahar passes through Qalat and Qalat “PRT Air” – 2 flights Shah Joy. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Individuals and Organisations

Designated individuals and organisations Listed below are all individuals and organisations currently designated in New Zealand as terrorist entities under the provisions of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002. It includes those listed with the United Nations (UN), pursuant to relevant Security Council Resolutions, at the time of the enactment of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002 and which were automatically designated as terrorist entities within New Zealand by virtue of the Acts transitional provisions, and those subsequently added by virtue of Section 22 of the Act. The list currently comprises 7 parts: 1. A list of individuals belonging to or associated with the Taliban By family name: • A • B,C,D,E • F, G, H, I, J • K, L • M • N, O, P, Q • R, S • T, U, V • W, X, Y, Z 2. A list of organisations belonging to or associated with the Taliban 3. A list of individuals belonging to or associated with ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaida By family name: • A • B • C, D, E • F, G, H • I, J, K, L • M, N, O, P • Q, R, S, T • U, V, W, X, Y, Z 4. A list of organisations belonging to or associated with ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaida 5. A list of entities where the designations have been deleted or consolidated • Individuals • Entities 6. A list of entities where the designation is pursuant to UNSCR 1373 1 7. A list of entities where the designation was pursuant to UNSCR 1373 but has since expired or been revoked Several identifiers are used throughout to categorise the information provided. -

The Coils of the Anaconda: America's

THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN BY C2009 Lester W. Grau Submitted to the graduate degree program in Military History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date defended: April 27, 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Lester W. Grau certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN Committee: ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date approved: April 27, 2009 ii PREFACE Generals have often been reproached with preparing for the last war instead of for the next–an easy gibe when their fellow-countrymen and their political leaders, too frequently, have prepared for no war at all. Preparation for war is an expensive, burdensome business, yet there is one important part of it that costs little–study. However changed and strange the new conditions of war may be, not only generals, but politicians and ordinary citizens, may find there is much to be learned from the past that can be applied to the future and, in their search for it, that some campaigns have more than others foreshadowed the coming pattern of modern war.1 — Field Marshall Viscount William Slim. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Hajji Din Mohammad Biography

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Hajji Din Mohammad Biography Hajji Din Mohammad, a former mujahedin fighter from the Khalis faction of Hezb-e Islami, became governor of the eastern province of Nangarhar after the assassination of his brother, Hajji Abdul Qadir, in July 2002. He is also the brother of slain commander Abdul Haq. He is currently serving as the provincial governor of Kabul Province. Hajji Din Mohammad’s great-grandfather, Wazir Arsala Khan, served as Foreign Minister of Afghanistan in 1869. One of Arsala Khan's descendents, Taj Mohammad Khan, was a general at the Battle of Maiwand where a British regiment was decimated by Afghan combatants. Another descendent, Abdul Jabbar Khan, was Afghanistan’s first ambassador to Russia. Hajji Din Mohammad’s father, Amanullah Khan Jabbarkhel, served as a district administer in various parts of the country. Two of his uncles, Mohammad Rafiq Khan Jabbarkhel and Hajji Zaman Khan Jabbarkhel, were members of the 7th session of the Afghan Parliament. Hajji Din Mohammad’s brothers Abdul Haq and Hajji Abdul Qadir were Mujahedin commanders who fought against the forces of the USSR during the Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan from 1980 through 1989. In 2001, Abdul Haq was captured and executed by the Taliban. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Governor of Nangarhar Province after the Soviet Occupation and was credited with maintaining peace in the province during the years of civil conflict that followed the Soviet withdrawal. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Vice President in the newly formed post-Taliban government of Hamid Karzai, but was assassinated by unknown assailants in 2002. -

The Thistle and the Drone

AKBAR AHMED HOW AMERICA’S WAR ON TERROR BECAME A GLOBAL WAR ON TRIBAL ISLAM n the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the United States declared war on terrorism. More than ten years later, the results are decidedly mixed. Here world-renowned author, diplomat, and scholar Akbar Ahmed reveals an important yet largely ignored result of this war: in many nations it has exacerbated the already broken relationship between central I governments and the largely rural Muslim tribal societies on the peripheries of both Muslim and non-Muslim nations. The center and the periphery are engaged in a mutually destructive civil war across the globe, a conflict that has been intensified by the war on terror. Conflicts between governments and tribal societies predate the war on terror in many regions, from South Asia to the Middle East to North Africa, pitting those in the centers of power against those who live in the outlying provinces. Akbar Ahmed’s unique study demonstrates that this conflict between the center and the periphery has entered a new and dangerous stage with U.S. involvement after 9/11 and the deployment of drones, in the hunt for al Qaeda, threatening the very existence of many tribal societies. American firepower and its vast anti-terror network have turned the war on terror into a global war on tribal Islam. And too often the victims are innocent children at school, women in their homes, workers simply trying to earn a living, and worshipers in their mosques. Bat- tered by military attacks or drone strikes one day and suicide bombers the next, the tribes bemoan, “Every day is like 9/11 for us.” In The Thistle and the Drone, the third vol- ume in Ahmed’s groundbreaking trilogy examin- ing relations between America and the Muslim world, the author draws on forty case studies representing the global span of Islam to demon- strate how the U.S. -

Quarterly Report

UNCLASSIFED/FOUO QUARTERLY REPORT 18 July 2011 This report is UNCLASSIFED in its entirety. Human Terrain Team-AF 24 Dr. Carol Burke: Social Scientist ([email protected]) CPT Marc Motyleski: Research Manager ([email protected]) Matthew Holley: Research Manager ([email protected]) Samantha Bruzan: Human Terrain Analyst ([email protected]) Azizullah Razawi: Human Terrain Analyst ([email protected]) UNCLASSIFED/FOUO UNCLASSIFED/FOUO Contents: ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................... 2 Exec Sum COMMERCE (Security, Drought, and Prices) by DR Burke ........................................ 3 FIG 1: Avenue of Approach ........................................................................................................ 6 Exec Sum RULE OF LAW by DR Burke ........................................................................................ 8 Exec Sum GOVERNANCE by DR Burke: .................................................................................... 10 Ghormach: ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Table 1: Ghormach District Shura Members ........................................................................... 11 Table 2: Ghormach District Shura Leadership ......................................................................... 12 Table 3: Sar Chasma -

Afghan Opiate Trade 2009.Indb

ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium Copyright © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), October 2009 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), in the framework of the UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme/Afghan Opiate Trade sub-Programme, and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC field offices for East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, Southern Africa, South Asia and South Eastern Europe also provided feedback and support. A number of UNODC colleagues gave valuable inputs and comments, including, in particular, Thomas Pietschmann (Statistics and Surveys Section) who reviewed all the opiate statistics and flow estimates presented in this report. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team, including, in particular, the Anti Narcotics Force of Pakistan, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan and the World Customs Organization. Thanks also go to the staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and of the United Nations Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Lead researcher, Afghan -

Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition

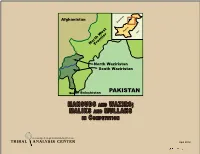

Afghanistan FGHANISTAN A PAKISTAN INIDA NorthFrontier West North Waziristan South Waziristan Balochistan PAKISTAN MAHSUDS AND WAZIRS; MALIKS AND MULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER April 2012 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition M AHSUDS AND W AZIRS ; M ALIKS AND M ULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition No patchwork scheme—and all our present recent schemes...are mere patchwork— will settle the Waziristan problem. Not until the military steam-roller has passed over the country from end to end, will there be peace. But I do not want to be the person to start that machine. Lord Curzon, Britain’s viceroy of India The great drawback to progress in Afghanistan has been those men who, under the pretense of religion, have taught things which were entirely contrary to the teachings of Mohammad, and that, being the false leaders of the religion. The sooner they are got rid of, the better. Amir Abd al-Rahman (Kabul’s Iron Amir) The Pashtun tribes have individual “personality” characteristics and this is a factor more commonly seen within the independent tribes – and their sub-tribes – than in the large tribal “confederations” located in southern Afghanistan, the Durranis and Ghilzai tribes that have developed in- termarried leadership clans and have more in common than those unaffiliated, independent tribes. Isolated and surrounded by larger, and probably later arriving migrating Pashtun tribes and restricted to poorer land, the Mahsud tribe of the Wazirs evolved into a nearly unique “tribal culture.” For context, it is useful to review the overarching genealogy of the Pashtuns. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$98.40 WINDHOEK - 24 July 2017 No. 6366 CONTENTS Page GOVERNMENT NOTICE No. 183 Publication of sanction list; issuing of freezing order and issuing of arms embargo: Prevention and Combating of Terrorist and Proliferation Activities Act, 2014 .............................................................. 1 ________________ Government Notice MINISTRY OF SAFETY AND SECURITY No. 183 2017 PUBLICATION OF SANCTION LIST; ISSUING OF FREEZING ORDER AND ISSUING OF ARMS EMBARGO: PREVENTION AND COMBATING OF TERRORIST AND PROLIFERATION ACTIVITIES ACT, 2014 In terms of – (a) Section 23(1)(a) of the Prevention and Combating of Terrorist and Proliferation Activities Act, 2014 (Act No. 4 of 2014), I publish, as Annexure, the sanction list issued by the United Nations Security Council pursuant to - (i) Security Council Resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011), 2253 (2015) and their successor resolutions, as updated on 20 July 2017; (b) Section 23(1)(b) of the Act referred to in paragraph (a), I issue a freezing order in respect of - (i) any funds, assets or economic resources that are owned or controlled directly or indirectly by the designated persons or organisations, without such funds or assets necessarily tied to a particular terrorist act, plot or threat; 2 Government Gazette 24 July 2017 6366 (ii) all funds, assets or economic resources that are wholly or jointly owned or controlled, directly or indirectly by the designated persons or organisations; (iii) funds, assets or economic resources derived or generated from funds or other assets; owned or controlled, directly or indirectly by the designated persons or organisations, including interests that may accrue to such funds or other assets; (iv) funds, other assets or economic resources of persons or organisations acting on behalf of or at the direction of the designated persons or organisations; or (v) any funds or assets held in a bank account as well as any additions that may come into such account after the initial or successive freezing.