Child Benefit: Fit for the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] Alice Dewing FREELANCE [email protected] Anna Pallai Amy Canavan [email protected] [email protected] Caitlin Allen Camilla Elworthy [email protected] [email protected] Elinor Fewster Emma Bravo [email protected] [email protected] Emma Draude Gabriela Quattromini [email protected] [email protected] Emma Harrow Grace Harrison [email protected] [email protected] Jacqui Graham Hannah Corbett [email protected] [email protected] Jamie-Lee Nardone Hope Ndaba [email protected] [email protected] Laura Sherlock Jess Duffy [email protected] [email protected] Ruth Cairns Kate Green [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan [email protected] Rosie Wilson [email protected] Siobhan Slattery [email protected] CONTENTS MACMILLAN PAN MANTLE TOR PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT MACMILLAN Nine Lives Danielle Steel Nine Lives is a powerful love story by the world’s favourite storyteller, Danielle Steel. Nine Lives is a thought-provoking story of lost love and new beginnings, by the number one bestseller Danielle Steel. After a carefree childhood, Maggie Kelly came of age in the shadow of grief. Her father, a pilot, died when she was nine. Maggie saw her mother struggle to put their lives back together. As the family moved from one city to the next, her mother warned her about daredevil men and to avoid risk at all cost. Following her mother’s advice, and forgoing the magic of first love with a high-school boyfriend who she thought too wild, Maggie married a good, dependable man. -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

One Nation: Power, Hope, Community

one nation power hope community power hope community Ed Miliband has set out his vision of One Nation: a country where everyone has a stake, prosperity is fairly shared, and we make a common life together. A group of Labour MPs, elected in 2010 and after, describe what this politics of national renewal means to them. It begins in the everyday life of work, family and local place. It is about the importance of having a sense of belonging and community, and sharing power and responsibility with people. It means reforming the state and the market in order to rebuild the economy, share power hope community prosperity, and end the living standards crisis. And it means doing politics in a different way: bottom up not top down, organising not managing. A new generation is changing Labour to change the country. Edited by Owen Smith and Rachael Reeves Contributors: Shabana Mahmood Rushanara Ali Catherine McKinnell Kate Green Gloria De Piero Lilian Greenwood Steve Reed Tristram Hunt Rachel Reeves Dan Jarvis Owen Smith Edited by Owen Smith and Rachel Reeves 9 781909 831001 1 ONE NATION power hope community Edited by Owen Smith & Rachel Reeves London 2013 3 First published 2013 Collection © the editors 2013 Individual articles © the author The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1998 to be identified as authors of this work. All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

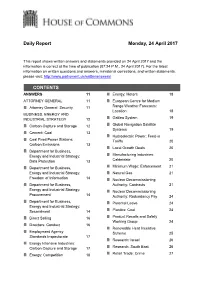

Daily Report Monday, 24 April 2017 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 24 April 2017 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 24 April 2017 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:24 P.M., 24 April 2017). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 11 Energy: Meters 18 ATTORNEY GENERAL 11 European Centre for Medium Attorney General: Security 11 Range Weather Forecasts: Location 18 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 12 Galileo System 19 Carbon Capture and Storage 12 Global Navigation Satellite Systems 19 Cement: Coal 13 Hydroelectric Power: Feed-in Coal Fired Power Stations: Tariffs 20 Carbon Emissions 13 Local Growth Deals 20 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: Manufacturing Industries: Data Protection 13 Calderdale 20 Department for Business, Minimum Wage: Enforcement 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Natural Gas 21 Freedom of Information 14 Nuclear Decommissioning Department for Business, Authority: Contracts 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Nuclear Decommissioning Procurement 14 Authority: Redundancy Pay 24 Department for Business, Parental Leave 24 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Secondment 14 Plastics: Coal 24 Direct Selling 16 Product Recalls and Safety Working Group 24 Directors: Conduct 16 Renewable Heat Incentive Employment Agency Scheme 25 Standards Inspectorate 17 Research: Israel 26 Energy Intensive Industries: Carbon Capture and Storage 17 Research: South East 26 Energy: -

Labour Party General Election 2017 Report Labour Party General Election 2017 Report

FOR THE MANY NOT THE FEW LABOUR PARTY GENERAL ELECTION 2017 REPORT LABOUR PARTY GENERAL ELECTION 2017 REPORT Page 7 Contents 1. Introduction from Jeremy Corbyn 07 2. General Election 2017: Results 11 3. General Election 2017: Labour’s message and campaign strategy 15 3.1 Campaign Strategy and Key Messages 16 3.2 Supporting the Ground Campaign 20 3.3 Campaigning with Women 21 3.4 Campaigning with Faith, Ethnic Minority Communities 22 3.5 Campaigning with Youth, First-time Voters and Students 23 3.6 Campaigning with Trade Unions and Affiliates 25 4. General Election 2017: the campaign 27 4.1 Manifesto and campaign documents 28 4.2 Leader’s Tour 30 4.3 Deputy Leader’s Tour 32 4.4 Party Election Broadcasts 34 4.5 Briefing and Information 36 4.6 Responding to Our Opponents 38 4.7 Press and Broadcasting 40 4.8 Digital 43 4.9 New Campaign Technology 46 4.10 Development and Fundraising 48 4.11 Nations and Regions Overview 49 4.12 Scotland 50 4.13 Wales 52 4.14 Regional Directors Reports 54 4.15 Events 64 4.16 Key Campaigners Unit 65 4.17 Endorsers 67 4.18 Constitutional and Legal services 68 5. Labour candidates 69 General Election 2017 Report Page 9 1. INTRODUCTION 2017 General Election Report Page 10 1. INTRODUCTION Foreword I’d like to thank all the candidates, party members, trade unions and supporters who worked so hard to achieve the result we did. The Conservatives called the snap election in order to increase their mandate. -

2021 SPRING Pan Macmillan Spring Catalogue 2021.Pdf

PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] * * * * * * * Alice Dewing Rosie Wilson [email protected] [email protected] Amy Canavan Siobhan Slattery [email protected] [email protected] Camilla Elworthy [email protected] * * * * * * * Elinor Fewster [email protected] FREELANCE Emma Bravo Anna Pallai [email protected] [email protected] Gabriela Quattromini Caitlin Allen [email protected] [email protected] Grace Harrison Emma Draude [email protected] [email protected] Hannah Corbett Emma Harrow [email protected] [email protected] Jess Duffy Jamie-Lee Nardone [email protected] [email protected] Kate Green Laura Sherlock [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan Ruth Cairns [email protected] [email protected] CONTENTs PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY MANTLE MACMILLAN PAN TOR BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT PICADOR The War of the Poor Eric Vuillard A short, brutal tale by the author of The Order of The Day: the story of a moment in Europe’s history when the poor rose up and banded together behind a fiery preacher, to challenge the entrenched powers of the ruling elite. The fight for equality begins in the streets. The history of inequality is a long and terrible one. And it’s not over yet. Short, sharp and devastating, The War of the Poor tells the story of a brutal episode from history, not as well known as tales of other popular uprisings, but one that deserves to be told. Sixteenth-century Europe: the Protestant Reformation takes on the powerful and the privileged. -

Policy Paper 2017/18

IDEAS INTO ACTION: BUILDING THE OPEN LEFT WWW.OPENLABOUR.ORG IDEAS INTO ACTION: BUILDING THE OPEN LEFT This document outlines an initial set of political positions for Open Labour, building on our launch statement. It provides a mandate to our newly renamed National Committee (NC) to carry out a programme of action, to make public arguments on behalf of the organisation, and to adopt campaigns within the Labour Party which meet our strategic and policy priorities. The document was proposed by our interim Management Committee to our Founding Conference in March 2017, which was attended by 23 0 people. It was adopted with the inclusion of a range of amendments. Those seeking further information about the contents of the document can get in touch with us at [email protected]. The document also marks the end of the steering phase of Open Labour’s development. As a statement of intent it is entitled ‘Ideas into Action: Building the Open Left’. This reflects our intention as an organisation not to resign to a polarised Labour Party where debate is curtailed and closed down, but to respond with ideas and action for something better. We will renew the realist strand of the Labour left as the ‘open left’, define and argue for this as a valid and independent tradition of thought and action, and campaign and organise to carry its objectives into being. The newly election National Committee would like to record our thanks to the Management Committee members who brought Open Labour through its first months. Interim Management Committee 2015-17 Tom Miller and Bev Craig (Co-chairs), Rose Grayston (Secretary), Alex Sobel (Treasurer), Jade Azim (Editor), Tom Williams (Membership), Ann Black, George Lindars-Hammond, Yue Ting Cheng, Andy Howell, Kaveh Azarhoosh, Joanne Rust, David Hamblin, Craig Dawson. -

Remembering Peter Townsend

obituary the aged. Even today, we are transfixed by the Remembering Peter combination of empirical quantitative research, passionate, beautiful writing and outrage at Townsend the conditions of old people in poor law institutions. His studies of old people were Peter Townsend was one of CPAG’s founders followed by his mammoth The Aged in the and our president. Despite his diverse interests Welfare State (with Wedderburn in 1965). and the many demands on his time, he still made the occasional visit to our offices, joining But Peter’s great work, Poverty in the United in with the policy debates and urging us to Kingdom, was not published until 1979 – think more radically and be more visionary. 1,216 pages and ten years after the survey on Both courteous and challenging, I often felt which it is based – for reasons he explains in that Peter thought we were just not quite bold the preface and which still make me wince to enough. read: they recruited their own field force, and the London School of Economics and Perhaps he was right. The calls in CPAG’s University of Essex computers were recent manifesto to reduce reliance on means- incompatible and so they had to enter the data tested benefits, increase universal child benefit twice. It is amazing that it was ever completed. and provide more help for the unemployed, It is a Great Work, the place from which disabled and lone parents repeat many of the poverty researchers should start. arguments that appeared in the CPAG manifesto of 1969. No wonder Peter was I am going to mention just three elements. -

Newcastle University E-Prints

Newcastle University e-prints Date deposited: 23 February 2010 Version of file: Published, final Peer Review Status: Peer reviewed Citation for published item: Veit-Wilson J. Remembering Peter Townsend. Poverty 133 2009, Summer 2009 22. Further information on publisher website: http://www.cpag.org.uk/ Publishers copyright statement: The definitive version of this article was published by Child Poverty Action Group, 2009. The definitive version should always be used when citing. Use Policy: The full-text may be used and/or reproduced and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not for profit purposes provided that: • A full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • A link is made to the metadata record in Newcastle e-prints • The full text is not changed in any way. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne. NE1 7RU. Tel. 0191 222 6000 obituary the aged. Even today, we are transfixed by the Remembering Peter combination of empirical quantitative research, passionate, beautiful writing and outrage at Townsend the conditions of old people in poor law institutions. His studies of old people were Peter Townsend was one of CPAG’s founders followed by his mammoth The Aged in the and our president. Despite his diverse interests Welfare State (with Wedderburn in 1965). and the many demands on his time, he still made the occasional visit to our offices, joining But Peter’s great work, Poverty in the United in with the policy debates and urging us to Kingdom , was not published until 1979 – think more radically and be more visionary. -

31/03/2017 Tulip Siddiq Written Question Afghanistan: Domestic Violence 31/03/2

Date Member(s) Type Topic (click for transcript) 31/03/2017 Tulip Siddiq Written Question Afghanistan: Domestic Violence 31/03/2017 Jim Cunningham Written Question Breastfeeding 30/03/2017 Jim Cunningham Written Question Pregnancy: Diets 30/03/2017 Jim Cunningham Written Question Endometriosis 29/03/2017 Richard Arkless, Rory Stewart, Desmond Swayne, Imran Oral Questions United Nations (Aid Programmes) Hussain 29/03/2017 Anne Main, Mike Freer, Dan Poulter, Jim Shannon, Ben Debate HIV Treatment Bradshaw, Peter Kyle, Thangam Debbonaire, Martyn Day, Sharon Hodgson, Nicola Blackwood 29/03/2017 Paula Sherriff Written Question Developing Countries: Equality 28/03/2017 Robert Flello Early Day Motion Sex-Selective and On-Demand Abortion 28/03/2017 Maria Caulfield, Tobias Ellwood, Helen Jones, Nusrat Ghani, Oral Questions Yazidi Captives: Daesh Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh, Robert Jenrick, Danny Kinahan, Emily Thornberry 28/03/2017 Tim Farron Written Question Maternity Services: Negligence 21/03/2017 Will Quince, Tim Loughton, Kevin Barron, Gavin Robinson, Debate Baby Loss (Public Health Guidelines) Philip Dunne 16/03/2017 Stewart Jackson Written Question Female Genital Mutilation 16/03/2017 Paul Blomfield, Mike Kane, Jeremy Wright, Andrew Oral Questions Domestic Violence Stephenson 16/03/2017 Amanda Solloway, Lucy Frazer, Robert Buckland, Peter Bone Oral Questions Violence Against Women and Girls 16/03/2017 Kate Osamor Written Question USA: Family Planning 15/03/2017 Tom Brake Written Question EU Aid 14/03/2017 Liz McInnes Written Question Gambia: Female -

Labour Party Conference

Labour Party Conference Progressive Fringe Guide The progressive fringe guide from Class This guide has been compiled by the Centre for Labour and Social Studies to promote the best fringes at Labour Party Conference 2014. We have tried to include as many as possible and would like to thank all of those involved. We hope you find it useful! What is Class? The Centre for Labour and Social Studies is a growing thinktank established by the trade union movement to act as a centre for left debate and discussion. Class works with a broad coalition of academics to develop alternative policy ideas and ensure the political agenda is on the side of working people. We produce policy papers, pamphlets and run events across the country. Class has the support of a growing number of trade unions including: ASLEF, BFAWU, CWU, GFTU, GMB, FEU, MU, NUM, NUT, PCS, PFA, TSSA, UCATT, UCU and Unite the Union. Find out more Visit our stand 142 in the Third Sector Zone of the Conference Centre or find out more from our website and Twitter. www.classonline.org.uk @classthinktank Progressive fringe listings 20 Saturday 18:00 Campaign for Labour Party Democracy Conference Lift Off! CLPD Rally & Delegates Briefing Jury’s Inn, 56 Bridgwater St, Entry: £3 (Concessions £1) Featuring: Diane Abbott MP; Ann Black NEC; Annelise Dodds MEP; Diana Holland, Unite; Kelvin Hopkins MP; Conrad Landin, Young Labour; Tosh McDonald, ASLEF; Pete Willsman; plus special guest; Chair: Gaye Johnston, CLPD Chair. * * * 12:30 Trades Union Congress Can Labour Deliver radical rail reform? The Hall, the Mechanics Institute, M1 6DD Featuring: Chair: Paul Nowak, Assistant General Secretary TUC; 21 September Sunday Mary Creagh MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Transport; Mick Cash, Acting General Secretary RMT; Mick Whelan, General Secretary, ASLEF; Andi Fox, Exec.