A Portfolio of Counter-Examples with Answers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 5.5 Right Triangle Trigonometry 385

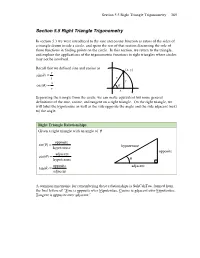

Section 5.5 Right Triangle Trigonometry 385 Section 5.5 Right Triangle Trigonometry In section 5.3 we were introduced to the sine and cosine function as ratios of the sides of a triangle drawn inside a circle, and spent the rest of that section discussing the role of those functions in finding points on the circle. In this section, we return to the triangle, and explore the applications of the trigonometric functions to right triangles where circles may not be involved. Recall that we defined sine and cosine as (x, y) y sin( θ ) = r r y x cos( θ ) = θ r x Separating the triangle from the circle, we can make equivalent but more general definitions of the sine, cosine, and tangent on a right triangle. On the right triangle, we will label the hypotenuse as well as the side opposite the angle and the side adjacent (next to) the angle. Right Triangle Relationships Given a right triangle with an angle of θ opposite sin( θ) = hypotenuse hypotenuse opposite adjacent cos( θ) = hypotenuse θ opposite adjacent tan( θ) = adjacent A common mnemonic for remembering these relationships is SohCahToa, formed from the first letters of “Sine is opposite over hypotenuse, Cosine is adjacent over hypotenuse, Tangent is opposite over adjacent.” 386 Chapter 5 Example 1 Given the triangle shown, find the value for cos( α) . The side adjacent to the angle is 15, and the 17 hypotenuse of the triangle is 17, so 8 adjacent 15 cos( α) = = α hypotenuse 17 15 When working with general right triangles, the same rules apply regardless of the orientation of the triangle. -

Geometry Honors Mid-Year Exam Terms and Definitions Blue Class 1

Geometry Honors Mid-Year Exam Terms and Definitions Blue Class 1. Acute angle: Angle whose measure is greater than 0° and less than 90°. 2. Adjacent angles: Two angles that have a common side and a common vertex. 3. Alternate interior angles: A pair of angles in the interior of a figure formed by two lines and a transversal, lying on alternate sides of the transversal and having different vertices. 4. Altitude: Perpendicular segment from a vertex of a triangle to the opposite side or the line containing the opposite side. 5. Angle: A figure formed by two rays with a common endpoint. 6. Angle bisector: Ray that divides an angle into two congruent angles and bisects the angle. 7. Base Angles: Two angles not included in the legs of an isosceles triangle. 8. Bisect: To divide a segment or an angle into two congruent parts. 9. Coincide: To lie on top of the other. A line can coincide another line. 10. Collinear: Lying on the same line. 11. Complimentary: Two angle’s whose sum is 90°. 12. Concave Polygon: Polygon in which at least one interior angle measures more than 180° (at least one segment connecting two vertices is outside the polygon). 13. Conclusion: A result of summary of all the work that has been completed. The part of a conditional statement that occurs after the word “then”. 14. Congruent parts: Two or more parts that only have the same measure. In CPCTC, the parts of the congruent triangles are congruent. 15. Congruent triangles: Two triangles are congruent if and only if all of their corresponding parts are congruent. -

Quadrilateral Theorems

Quadrilateral Theorems Properties of Quadrilaterals: If a quadrilateral is a TRAPEZOID then, 1. at least one pair of opposite sides are parallel(bases) If a quadrilateral is an ISOSCELES TRAPEZOID then, 1. At least one pair of opposite sides are parallel (bases) 2. the non-parallel sides are congruent 3. both pairs of base angles are congruent 4. diagonals are congruent If a quadrilateral is a PARALLELOGRAM then, 1. opposite sides are congruent 2. opposite sides are parallel 3. opposite angles are congruent 4. consecutive angles are supplementary 5. the diagonals bisect each other If a quadrilateral is a RECTANGLE then, 1. All properties of Parallelogram PLUS 2. All the angles are right angles 3. The diagonals are congruent If a quadrilateral is a RHOMBUS then, 1. All properties of Parallelogram PLUS 2. the diagonals bisect the vertices 3. the diagonals are perpendicular to each other 4. all four sides are congruent If a quadrilateral is a SQUARE then, 1. All properties of Parallelogram PLUS 2. All properties of Rhombus PLUS 3. All properties of Rectangle Proving a Trapezoid: If a QUADRILATERAL has at least one pair of parallel sides, then it is a trapezoid. Proving an Isosceles Trapezoid: 1st prove it’s a TRAPEZOID If a TRAPEZOID has ____(insert choice from below) ______then it is an isosceles trapezoid. 1. congruent non-parallel sides 2. congruent diagonals 3. congruent base angles Proving a Parallelogram: If a quadrilateral has ____(insert choice from below) ______then it is a parallelogram. 1. both pairs of opposite sides parallel 2. both pairs of opposite sides ≅ 3. -

Properties of Equidiagonal Quadrilaterals (2014)

Forum Geometricorum Volume 14 (2014) 129–144. FORUM GEOM ISSN 1534-1178 Properties of Equidiagonal Quadrilaterals Martin Josefsson Abstract. We prove eight necessary and sufficient conditions for a convex quadri- lateral to have congruent diagonals, and one dual connection between equidiag- onal and orthodiagonal quadrilaterals. Quadrilaterals with both congruent and perpendicular diagonals are also discussed, including a proposal for what they may be called and how to calculate their area in several ways. Finally we derive a cubic equation for calculating the lengths of the congruent diagonals. 1. Introduction One class of quadrilaterals that have received little interest in the geometrical literature are the equidiagonal quadrilaterals. They are defined to be quadrilat- erals with congruent diagonals. Three well known special cases of them are the isosceles trapezoid, the rectangle and the square, but there are other as well. Fur- thermore, there exists many equidiagonal quadrilaterals that besides congruent di- agonals have no special properties. Take any convex quadrilateral ABCD and move the vertex D along the line BD into a position D such that AC = BD. Then ABCD is an equidiagonal quadrilateral (see Figure 1). C D D A B Figure 1. An equidiagonal quadrilateral ABCD Before we begin to study equidiagonal quadrilaterals, let us define our notations. In a convex quadrilateral ABCD, the sides are labeled a = AB, b = BC, c = CD and d = DA, and the diagonals are p = AC and q = BD. We use θ for the angle between the diagonals. The line segments connecting the midpoints of opposite sides of a quadrilateral are called the bimedians and are denoted m and n, where m connects the midpoints of the sides a and c. -

Geometrygeometry

Park Forest Math Team Meet #3 GeometryGeometry Self-study Packet Problem Categories for this Meet: 1. Mystery: Problem solving 2. Geometry: Angle measures in plane figures including supplements and complements 3. Number Theory: Divisibility rules, factors, primes, composites 4. Arithmetic: Order of operations; mean, median, mode; rounding; statistics 5. Algebra: Simplifying and evaluating expressions; solving equations with 1 unknown including identities Important Information you need to know about GEOMETRY… Properties of Polygons, Pythagorean Theorem Formulas for Polygons where n means the number of sides: • Exterior Angle Measurement of a Regular Polygon: 360÷n • Sum of Interior Angles: 180(n – 2) • Interior Angle Measurement of a regular polygon: • An interior angle and an exterior angle of a regular polygon always add up to 180° Interior angle Exterior angle Diagonals of a Polygon where n stands for the number of vertices (which is equal to the number of sides): • • A diagonal is a segment that connects one vertex of a polygon to another vertex that is not directly next to it. The dashed lines represent some of the diagonals of this pentagon. Pythagorean Theorem • a2 + b2 = c2 • a and b are the legs of the triangle and c is the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) c a b • Common Right triangles are ones with sides 3, 4, 5, with sides 5, 12, 13, with sides 7, 24, 25, and multiples thereof—Memorize these! Category 2 50th anniversary edition Geometry 26 Y Meet #3 - January, 2014 W 1) How many cm long is segment 6 XY ? All measurements are in centimeters (cm). -

Right Triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem Related?

Activity Assess 9-6 EXPLORE & REASON Right Triangles and Consider △ ABC with altitude CD‾ as shown. the Pythagorean B Theorem D PearsonRealize.com A 45 C 5√2 I CAN… prove the Pythagorean Theorem using A. What is the area of △ ABC? Of △ACD? Explain your answers. similarity and establish the relationships in special right B. Find the lengths of AD‾ and AB‾ . triangles. C. Look for Relationships Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ ABC VOCABULARY by the length of one of its sides. Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ACD by the length of one of its sides. Make a conjecture that explains • Pythagorean triple the results. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How are similarity in right triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem related? Remember that the Pythagorean Theorem and its converse describe how the side lengths of right triangles are related. THEOREM 9-8 Pythagorean Theorem If a triangle is a right triangle, If... △ABC is a right triangle. then the sum of the squares of the B lengths of the legs is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse. c a A C b 2 2 2 PROOF: SEE EXAMPLE 1. Then... a + b = c THEOREM 9-9 Converse of the Pythagorean Theorem 2 2 2 If the sum of the squares of the If... a + b = c lengths of two sides of a triangle is B equal to the square of the length of the third side, then the triangle is a right triangle. c a A C b PROOF: SEE EXERCISE 17. Then... △ABC is a right triangle. -

"Perfect Squares" on the Grid Below, You Can See That Each Square Has Sides with Integer Length

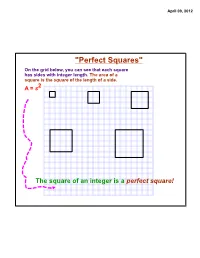

April 09, 2012 "Perfect Squares" On the grid below, you can see that each square has sides with integer length. The area of a square is the square of the length of a side. A = s2 The square of an integer is a perfect square! April 09, 2012 Square Roots and Irrational Numbers The inverse of squaring a number is finding a square root. The square-root radical, , indicates the nonnegative square root of a number. The number underneath the square root (radical) sign is called the radicand. Ex: 16 = 121 = 49 = 144 = The square of an integer results in a perfect square. Since squaring a number is multiplying it by itself, there are two integer values that will result in the same perfect square: the positive integer and its opposite. 2 Ex: If x = (perfect square), solutions would be x and (-x)!! Ex: a2 = 25 5 and -5 would make this equation true! April 09, 2012 If an integer is NOT a perfect square, its square root is irrational!!! Remember that an irrational number has a decimal form that is non- terminating, non-repeating, and thus cannot be written as a fraction. For an integer that is not a perfect square, you can estimate its square root on a number line. Ex: 8 Since 22 = 4, and 32 = 9, 8 would fall between integers 2 and 3 on a number line. -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 April 09, 2012 Approximate where √40 falls on the number line: Approximate where √192 falls on the number line: April 09, 2012 Topic Extension: Simplest Radical Form Simplify the radicand so that it has no more perfect-square factors. -

Introduction to Geometry" ©2014 Aops Inc

Excerpt from "Introduction to Geometry" ©2014 AoPS Inc. www.artofproblemsolving.com CHAPTER 12. CIRCLES AND ANGLES (a) Consider the circle with diameter OP. Call this circle . Why must hit O in at least two di↵erent C C points? (b) Why is it impossible for to hit O in three di↵erent points? Hints: 530 C (c) Let the points where hits O be A and B. Prove that \PAO = \PBO = 90 . C ◦ (d) Prove that PA and PB are tangent to O. (e)? Now for the tricky part – proving that these are the only two tangents. Suppose D is on O such that PD is tangent to O. Why must D be on ? Hints: 478 C (f) Why does the previous part tell us that PA! and PB! are the only lines through P tangent to O? 12.3.6? O is tangent to all four sides of rhombus ABCD, AC = 24, and AB = 15. (a) Prove that AC and BD meet at O (i.e., prove that the intersection of the diagonals of ABCD is the center of the circle.) Hints: 439 (b) What is the area of O? Hints: 508 12.4 Problems Problems Problem 12.19: A quadrilateral is said to be a cyclic quadrilateral if a circle can be drawn that passes through all four of its vertices. Prove that if ABCD is a cyclic quadrilateral, then \A + \C = 180◦. C Problem 12.20: In the figure, PC is tangent to the circle and PD 70◦ bisects \CPE. Furthermore, CD = 70◦, DE = 50◦, and \DQE = P B Q D 40◦. -

Cyclic Quadrilaterals

GI_PAGES19-42 3/13/03 7:02 PM Page 1 Cyclic Quadrilaterals Definition: Cyclic quadrilateral—a quadrilateral inscribed in a circle (Figure 1). Construct and Investigate: 1. Construct a circle on the Voyage™ 200 with Cabri screen, and label its center O. Using the Polygon tool, construct quadrilateral ABCD where A, B, C, and D are on circle O. By the definition given Figure 1 above, ABCD is a cyclic quadrilateral (Figure 1). Cyclic quadrilaterals have many interesting and surprising properties. Use the Voyage 200 with Cabri tools to investigate the properties of cyclic quadrilateral ABCD. See whether you can discover several relationships that appear to be true regardless of the size of the circle or the location of A, B, C, and D on the circle. 2. Measure the lengths of the sides and diagonals of quadrilateral ABCD. See whether you can discover a relationship that is always true of these six measurements for all cyclic quadrilaterals. This relationship has been known for 1800 years and is called Ptolemy’s Theorem after Alexandrian mathematician Claudius Ptolemaeus (A.D. 85 to 165). 3. Determine which quadrilaterals from the quadrilateral hierarchy can be cyclic quadrilaterals (Figure 2). 4. Over 1300 years ago, the Hindu mathematician Brahmagupta discovered that the area of a cyclic Figure 2 quadrilateral can be determined by the formula: A = (s – a)(s – b)(s – c)(s – d) where a, b, c, and d are the lengths of the sides of the a + b + c + d quadrilateral and s is the semiperimeter given by s = 2 . Using cyclic quadrilaterals, verify these relationships. -

Cyclic and Bicentric Quadrilaterals G

Cyclic and Bicentric Quadrilaterals G. T. Springer Email: [email protected] Hewlett-Packard Calculators and Educational Software Abstract. In this hands-on workshop, participants will use the HP Prime graphing calculator and its dynamic geometry app to explore some of the many properties of cyclic and bicentric quadrilaterals. The workshop will start with a brief introduction to the HP Prime and an overview of its features to get novice participants oriented. Participants will then use ready-to-hand constructions of cyclic and bicentric quadrilaterals to explore. Part 1: Cyclic Quadrilaterals The instructor will send you an HP Prime app called CyclicQuad for this part of the activity. A cyclic quadrilateral is a convex quadrilateral that has a circumscribed circle. 1. Press ! to open the App Library and select the CyclicQuad app. The construction consists DEGH, a cyclic quadrilateral circumscribed by circle A. 2. Tap and drag any of the points D, E, G, or H to change the quadrilateral. Which of the following can DEGH never be? • Square • Rhombus (non-square) • Rectangle (non-square) • Parallelogram (non-rhombus) • Isosceles trapezoid • Kite Just move the points of the quadrilateral around enough to convince yourself for each one. Notice HDE and HE are both inscribed angles that subtend the entirety of the circle; ≮ ≮ likewise with DHG and DEG. This leads us to a defining characteristic of cyclic ≮ ≮ quadrilaterals. Make a conjecture. A quadrilateral is cyclic if and only if… 3. Make DEGH into a kite, similar to that shown to the right. Tap segment HE and press E to select it. Now use U and D to move the diagonal vertically. -

Math 1330 - Section 4.1 Special Triangles

Math 1330 - Section 4.1 Special Triangles In this section, we’ll work with some special triangles before moving on to defining the six trigonometric functions. Two special triangles are 30 − 60 − 90 triangles and 45 − 45 − 90 triangles. With little additional information, you should be able to find the lengths of all sides of one of these special triangles. First we’ll review some conventions when working with triangles. We label angles with capital letters and sides with lower case letters. We’ll use the same letter to refer to an angle and the side opposite it, although the angle will be a capital letter and the side will be lower case. In this section, we will work with right triangles. Right triangles have one angle which measures 90 degrees, and two other angles whose sum is 90 degrees. The side opposite the right angle is called the hypotenuse, and the other two sides are called the legs of the triangle. A labeled right triangle is shown below. B c a A C b Recall: When you are working with a right triangle, you can use the Pythagorean Theorem to help you find the length of an unknown side. In a right triangle ABC with right angle C, 2 2 2 a + b = c . Example: In right triangle ABC with right angle C, if AB = 12 and AC = 8, find BC. 1 Special Triangles In a 30 − 60 − 90 triangle, the lengths of the sides are proportional. If the shorter leg (the side opposite the 30 degree angle) has length a, then the longer leg has length 3a and the hypotenuse has length 2a. -

Isosceles Triangles on a Geoboard

Isosceles Triangles on a Geoboard About Illustrations: Illustrations of the Standards for Mathematical Practice (SMP) consist of several pieces, including a mathematics task, student dialogue, mathematical overview, teacher reflection questions, and student materials. While the primary use of Illustrations is for teacher learning about the SMP, some components may be used in the classroom with students. These include the mathematics task, student dialogue, and student materials. For additional Illustrations or to learn about a professional development curriculum centered around the use of Illustrations, please visit mathpractices.edc.org. About the Isosceles Triangles on a Geoboard Illustration: This Illustration’s student dialogue shows the conversation among three students who are looking for how many isosceles triangles can be constructed on a geoboard given only one side. After exploring several cases where the known side is one of the congruent legs, students then use the known side as the base and make an interesting observation. Highlighted Standard(s) for Mathematical Practice (MP) MP 1: Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. MP 5: Use appropriate tools strategically. MP 7: Look for and make use of structure. Target Grade Level: Grades 6–7 Target Content Domain: Geometry Highlighted Standard(s) for Mathematical Content 7.G.A.2 Draw (freehand, with ruler and protractor, and with technology) geometric shapes with given conditions. Focus on constructing triangles from three measures of angles or sides, noticing when the conditions determine a unique triangle, more than one triangle, or no triangle. Math Topic Keywords: isosceles triangles, geoboard © 2016 by Education Development Center. Isosceles Triangles on a Geoboard is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.