Life and Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoroton Society Publications

THOROTON SOCIETY Record Series Blagg, T.M. ed., Seventeenth Century Parish Register Transcripts belonging to the peculiar of Southwell, Thoroton Society Record Series, 1 (1903) Leadam, I.S. ed., The Domesday of Inclosures for Nottinghamshire. From the Returns to the Inclosure Commissioners of 1517, in the Public Record Office, Thoroton Society Record Series, 2 (1904) Phillimore, W.P.W. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. I: Henry VII and Henry VIII, 1485 to 1546, Thoroton Society Record Series, 3 (1905) Standish, J. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. II: Edward I and Edward II, 1279 to 1321, Thoroton Society Record Series, 4 (1914) Tate, W.E., Parliamentary Land Enclosures in the county of Nottingham during the 18th and 19th Centuries (1743-1868), Thoroton Society Record Series, 5 (1935) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem and other Inquisitions relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. III: Edward II and Edward III, 1321 to 1350, Thoroton Society Record Series, 6 (1939) Hodgkinson, R.F.B., The Account Books of the Gilds of St. George and St. Mary in the church of St. Peter, Nottingham, Thoroton Society Record Series, 7 (1939) Gray, D. ed., Newstead Priory Cartulary, 1344, and other archives, Thoroton Society Record Series, 8 (1940) Young, E.; Blagg, T.M. ed., A History of Colston Bassett, Nottinghamshire, Thoroton Society Record Series, 9 (1942) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Bonds and Allegations for Marriage Licenses in the Archdeaconry Court of Nottingham, 1754-1770, Thoroton Society Record Series, 10 (1947) Blagg, T.M. -

GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON: a Literary-Biographical-Critical

1 GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON: A literary-biographical-critical database 2: by year CODE: From National Library in Taiwan UDD: unpublished doctoral dissertation Books and Articles Referring to Byron, by year 1813-1824: Anon. A Sermon on the Death of Byron, by a Layman —— Lines on the departure of a great poet from this country, 1816 —— An Address to the Rt. Hon. Lord Byron, with an opinion on some of his writings, 1817 —— The radical triumvirate, or, infidel Paine, Lord Byron, and Surgeon Lawrenge … A Letter to John Bull, from a Oxonian resident in London, 1820 —— A letter to the Rt. Hon. Lord Byron, protesting against the immolation of Gray, Cowper and Campbell, at the shrine of Pope, The Pamphleteer Vol 8, 1821 —— Lord Byron’s Plagiarisms, Gentleman’s Magazine, April 1821; Lord Byron Defended from a Charge of Plagiarism, ibid —— Plagiarisms of Lord Byron Detected, Monthly Magazine, August 1821, September 1821 —— A letter of expostulation to Lord Byron, on his present pursuits; with animadversions on his writings and absence from his country in the hour of danger, 1822 —— Uriel, a poetical address to Lord Byron, written on the continent, 1822 —— Lord Byron’s Residence in Greece, Westminster Review July 1824 —— Full Particulars of the much lamented Death of Lord Byron, with a Sketch of his Life, Character and Manners, London 1824 —— Robert Burns and Lord Byron, London Magazine X, August 1824 —— A sermon on the death of Lord Byron, by a Layman, 1824 Barker, Miss. Lines addressed to a noble lord; – his Lordship will know why, – by one of the small fry of the Lakes 1815 Belloc, Louise Swanton. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing theUMI World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Order Number 8803923 Throwing the scabbard away: Byron’s battle against the censors o f Don Juan Blann, Troy Robinson, Jr., D.A. Middle Tennessee State University, 1987 Copyright ©1988 by Blann, Troy Robinson, Jr. -

08 North Italy 1816

1 BYRON’S CORRESPONDENCE AND JOURNALS 08: FROM NORTH ITALY, NOVEMBER 1816 Edited by Peter Cochran Work in progress, with frequent updates [indicated]. Letters not in the seventeen main files may be found in those containing the correspondences Byron / Annbella, Byron / Murray, Byron / Hobhouse, Byron / Moore, Byron / Scott, Byron / Kinnaird, Byron / The Shelleys , or Byron / Hoppner . UPDATED November 2010. Abbreviations B.: Byron; Mo: Moore; H.: Hobhouse; K.: Kinnaird; Mu.: Murray; Sh.: Shelley 1922: Lord Byron’s Correspondence Chiefly with Lady Melbourne, Mr Hobhouse, The Hon. Douglas Kinnaird, and P.B.Shelley (2 vols., John Murray 1922). BB: Byron’s Bulldog: The Letters of John Cam Hobhouse to Lord Byron, ed. Peter W.Graham (Columbus Ohio 1984) BLJ: Byron, George Gordon, Lord. Byron’s Letters and Journals . Ed. Leslie A. Marchand, 13 vols. London: John Murray 1973–94. Burnett: T.A.J. Burnett, The Rise and Fall of a Regency Dandy , John Murray, 1981. CSS: The Life and Correspondence of the Late Robert Southey , ed. C.C.Southey, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 6 vols 1849-1850. J.W.W.: Selections from the letters of Robert Southey , Ed. John Wood Warter, 4 vols, Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1856. LJ: The Works of Lord Byron, Letters and Journals . Ed. R. E. Prothero, 6 vols. London: John Murray, 1899-1904. LJM: The Letters of John Murray to Lord Byron . Ed. Andrew Nicholson, Liverpool University Press, 2007. NLS: National Library of Scotland. Q: Byron: A Self-Portrait; Letters and Diaries 1798 to 1824 . Ed. Peter Quennell, 2 vols, John Murray, 1950. Ramos: The letters of Robert Southey to John May, 1797 to 1838. -

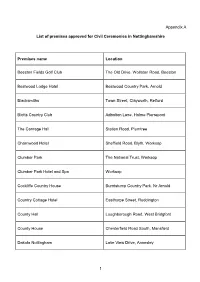

1 Appendix a List of Premises Approved for Civil Ceremonies In

Appendix A List of premises approved for Civil Ceremonies in Nottinghamshire Premises name Location Beeston Fields Golf Club The Old Drive, Wollaton Road, Beeston Bestwood Lodge Hotel Bestwood Country Park, Arnold Blacksmiths Town Street, Clayworth, Retford Blotts Country Club Adbolton Lane, Holme Pierrepont The Carriage Hall Station Road, Plumtree Charnwood Hotel Sheffield Road, Blyth, Worksop Clumber Park The National Trust, Worksop Clumber Park Hotel and Spa Worksop Cockliffe Country House Burntstump Country Park. Nr Arnold Country Cottage Hotel Easthorpe Street, Ruddington County Hall Loughborough Road, West Bridgford County House Chesterfield Road South, Mansfield Dakota Nottingham Lake View Drive, Annesley 1 Premises name Location Deincourt Hotel London Road, Newark DH Lawrence Heritage Centre (closed for bookings) Mansfield Road, Eastwood East Bridgfod Hill Kirk Hill, East Bridgford Eastwood Hall Mansfield Road, Eastwood Forever Green Restaurant Southwell Road, Mansfield The Full Moon Main Street, Morton, Southwell The Gilstrap Castle Gate, Newark Goosedale Goosedale Lane, Bestwood Village Grange Hall Vicarage Lane, Radcliffe on Trent Hodsock Priory Blyth, Nr Worksop Holme Pierrepont Hall Holme Pierrepont, Nottingham Kelham Hall Kelham, Newark Kelham House Country Manor Hotel Main Street, Kelham, Newark Langar Hall Langar, Nottinghamshire Leen Valley Golf Club Wigwam Lane, Hucknall 2 Premises name Location Lion Hotel Bridge Street, Worksop Mansfield Manor Hotel Carr Bank Park, Windmill Lane, Mansfield The Mill, Rufford Country -

Some Documents Relating to Lord Byron's Finances During 1812-18

1 Some documents relating to Lord Byron’s Finances during 1812-18 1: Byron’s Bank Account with Hoare and Company, 37 Fleet Street 2: Financial material in the John Murray Archive relative to the account with Hoare’s 3: Byron’s account with Hammersley’s Bank, Pall Mall 1: Byron’s Bank Account with Hoare and Company, 37 Fleet Street This is as full an edition of Byron’s first-line bank account during his Years of Fame (1812 - 1816) as I have been able to construct. He had another account with Hammersley’s, for which see below. I think I have been able to identify most of the people and organisations named on the left-hand, debit side of the ledgers. If anyone disagrees with any of my attributions, or has a different interpretation, I should like to hear from them. Hoares date the foundation of their bank from July 5th 1672, when Richard Hoare was granted the Freedom of the Goldsmiths’ Company. In 1673 he took over the goldsmith’s business of his deceased master, and moved it in 1690 to 37 Fleet Street at the Sign of the Golden Bottle, where the bank’s premises have been ever since. All partners in the Bank have been his direct descendants. Hoare was knighted by Queen Anne, and was Lord Mayor of London in 1712. The Bank skilfully avoided disaster when the South Sea Bubble burst in 1721, and Sir Richard’s younger son, also named Richard, was knighted as a reward for his peacekeeping services during the Jacobite uprising of 1745. -

The Hucknall Byron Festival

th Friday 14 July Acknowledgements: The Hucknall Byron Festival The Award winning Newstead Brass Band Committee wish to express their appreciation to the Will finalize the week’s festival with following organisations that have sponsored the festival The Hucknall a musical extravaganza at the John or given their help and support with various activities: Godber Centre commencing 7.30pm Byron Festival During the evening there will be an awards ceremony to present the winners of the poetry, arts, and 2017 photographic competitions with their prizes - Tickets £5.00 available from the John Godber Centreor £6.00 on the door. Entries are invited to the poetry, art and photographic competitions. Closing date for the poetry competition will be on Friday 16th June 2017. Entries to be sent by email to [email protected] otherwise by agreement. Closing date for all other competitions will be on Friday 14th July at 10.30am All competitions will be based on the Festival theme, ‘Byron in Venice – it’s carnival time’ All entries will be placed on public display at the Byron in Venice John Godber Centre on Friday 14th July from 10.30am onwards ahead of the awards ceremony later the It’s Carnival Time same evening. All enquiries to: [email protected] or by Friday 7th to Friday 14th July phone 01636 813818. Family Fun and Entertainment Lincoln Green Brewery & The Station Hotel Hucknall Please contact the John Godber Centre George Street Working Men’s Club on 0115 963 9633 for all events, Hucknall Beauvale Community and Youth Charity including bookings where necessary, unless otherwise stated, or email: [email protected] Where applicable cheques should be made payable to: The Hucknall Byron Festival Committee Account Fees at the Abbey for this event (except where stated otherwise): Entry to grounds: £6.00 per car (normal rate) Entry to house: £1.00 per person with a copy of this Byron Festival leaflet. -

Memoirs of the Life of Sir Samuel Romilly, Written by Himself, Ed. By

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 4c 102,1 MEMOIRS THE LIFE OF SIR SAMUEL ROMILLY, WRITTEN BY HIMSELF; WITH A SELECTION FROM HIS CORRESPONDENCE. EDITED BY HIS SONS. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. III. LONDON: JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. MDCCCXL. 1031. London : Printed by A. Spottiswoode, New- Street- Square. CONTENTS THE THIRD VOLUME. DIARY OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIFE OF SIR SAMUEL ROMILL Y — {continued). 1812. Slave trade ; Registry of slaves Bristol election; candidates; Mr. Protheroe. — Resolution of the Independent Club, and letter respecting it Mr. Protheroe; Hunt Address to the electors. — Mr. Rider's motion, police of the metro polis ; increase of crime. — Abuses in Ecclesiastical Courts ; Sir Wm. Scott. — Bristol election ; letter to Mr. Edge. — Reversion Bill. — Bill to repeal 39 Eliz. — Transportation to New South Wales. — The Regent's determination to re tain the ministers; his letter to the Duke of York. — Colonel M'Mahon's sinecure. — Delays in the Court of Chancery ; Michael Angelo Taylor. — Master in Chancery not fit mem ber of a committee to inquire into the delays of the court. — Expulsion of Walsh from the House of Commons. — Local Poor Bills; Stroud. — Military punishments; Brougham. — Bill to repeal 39 Eliz. ; Lord Ellenborough. — Abuses of charitable trusts ; Mr. Lockhart. — Visit to Bristol, reception, Speech second address to the electors. — Military punishments. — Cobbett's attack. — Committee on the delays in the Court of Chancery. — Disqualifying laws against Catholics. -

Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1t1nf085 No online items Inventory of the Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Sara Gunasekara & Jared Campbell Department of Special Collections General Library University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616-5292 Phone: (530) 752-1621 Fax: (530) 754-5758 Email: [email protected] © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Christopher A. D-435 1 Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Collector: Reynolds, Christopher A. Title: Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Date (inclusive): circa 1800-1985 Extent: 15.3 linear feet Abstract: Christopher A. Reynolds, Professor of Music at the University of California, Davis, has identified and collected sheet music written by women composers active in North America and England. This collection contains over 3000 songs and song publications mostly published between 1850 and 1950. The collection is primarily made up of songs, but there are also many works for solo piano as well as anthems and part songs. In addition there are books written by the women song composers, a letter written by Virginia Gabriel in the 1860s, and four letters by Mrs. H.H.A. Beach to James Francis Cooke from the 1920s. Physical location: Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Repository: University of California, Davis. General Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Davis, California 95616-5292 Collection number: D-435 Language of Material: Collection materials in English Biography Christoper A. Reynolds received his PhD from Princeton University. He is Professor of Music at the University of Californa, Davis and author of Papal Patronage and the Music of St. -

London, April 26Th–July 30Th 1816 84

84 London, April 26th–July 30th 1816 Mid-1816 April 26th-July 30th 1816 Edited from BL Add. Mss. 47232 and 56536 There is much variety and interest in this section of the diary, which covers the time between Byron’s departure for the continent on April 25th 1816 and that of Hobhouse on July 30th (for which he is already preparing on June 5th). The events chronicled should climax in Sheridan’s funeral, on July 13th; but that is an anti-climactic affair. They might have climaxed with a successful romantic assignation on June 24th, but Hobhouse is as luckless and inept here as ever he is. The high-point would be Miss Somerville’s delivery of his prologue to Maturin’s Bertram , at Drury Lane on May 9th, if only that were something of which he felt proud. For the rest, Hobhouse is throughout anxious over the sale of his Letters from Paris , a work, it seems, much-praised but little purchased. The success of Caroline Lamb’s shameless Glenarvon , published on May 9th and into its second edition by late June, does his ego no good. His reading in Mungo Park, and the tales of the war with the Nepalese, and of Napoleon, which his brother Henry brings from his travels, add an incidental exotic interest; and there are vivid glimpses of Coleridge, Sebastiani, Kean, Benjamin Constant, and others. Hobhouse’s exit from the country is effected in a very strange and disturbing manner. Friday April 26th 1816: Did little or nothing in the morning. Met Bainbridge, 1 who told me that Cuthbert 2 had told him that he defended Lord Byron, as having separated only on common causes, when Lord Auckland 3 said, “I beg your pardon – Brougham has told me it is something ‘too horrid to mention’”. -

The Romantic Poetry Handbook

The Romantic Poetry Handbook This comprehensive survey of British Romantic poetry explores the work of six poets whose names are most closely associated with the Romantic era – Wordsworth, Coleridge, Blake, Keats, Byron, and Shelley – as well as works by other significant but less widely studied poets such as Leigh Hunt, Charlotte Smith, Felicia Hemans, and Letitia Elizabeth Landon. Along with its exceptional coverage, the volume is alert to relevant contexts, and opens up ways of understanding Romantic poetry. The Romantic Poetry Handbook encompasses the entire breadth of the Romantic Movement, from Anna Laetitia Barbauld to Thomas Lovell Beddoes and John Clare. In its central section ‘Readings’ it explores tensions, change, and continuity within the Romantic Movement, and examines a wide range of individual poems and poets through sensitive, attentive, and accessible analyses. In addition, the authors provide a full introduction, a detailed historical and cultural timeline, biographies of the poets whose works are featured, and a helpful guide to further reading. The Romantic Poetry Handbook is an ideal text for undergraduate and postgraduate students of British Romantic poetry. It will also appeal to those with a general interest in poetry and Romantic literature. Michael O’Neill, is Professor of English at Durham University, UK. He has published widely on many aspects of Romantic literature, especially the work of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Victorian poetry, and an array of British, Irish, and American twentieth- and twenty-first-century poets. His most recent book is, as editor, John Keats in Context (2017). He has also published three volumes of poetry. Madeleine Callaghan, is Lecturer in Romantic Literature at the University of Sheffield, UK. -

1 Byron Society of America Archive

Byron Society of America Archive Founded by Marsha M. Manns and Leslie A. Marchand An Inventory Creators: Manns, Marsha M. Marchand, Leslie Alexis, 1900-1999 Title: Byron Society of America Archive Dates: 1953-2005, bulk 1973-2005 Abstract: Correspondence, newspaper clippings, financial files, newsletters, and articles document the founding and activities of the Byron Society of America. The Society brings together Byron scholars and devotees to support scholarship, tours, conferences, lectures, and programs. Extent: 57 boxes, 33 linear feet Language: English Repository: Drew University Library, Madison NJ Historical Note The Byron Society of America was founded in 1973 by Marsha M. Manns and Leslie A. Marchand to further the study of the life and work of Romantic poet George Gordon Byron, Lord Byron (1788-1824). The Society, originally referred to as The American Committee of the Byron Society, chose Byron’s birthday, January 22, for the founding date. The Society brings together Byron scholars throughout the United States and Canada to promote scholarship, correspondence, lectures, exhibits, conferences and tours. Early on, the Society published a newsletter that disseminated new scholarship on Byron and Romanticism. Additionally, the Society encouraged correspondence by connecting members with each other. In 1992, Manns and Marchand began discussions with the University of Delaware to provide institutional support to the Byron Society of America. In 1995, the operations of the Society were moved to the University of Delaware and Dr. Charles E. Robinson 1 became the executive director. Also in 1995, the Byron Society Collection at the University of Delaware was founded by Marsha M. Manns and Leslie A.