Open Source Digital Camera on Field Programmable Gate Arrays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debugging System for Openrisc 1000- Based Systems

Debugging System for OpenRisc 1000- based Systems Nathan Yawn [email protected] 05/12/09 Copyright (C) 2008 Nathan Yawn Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license should be included with this document. If not, the license may be obtained from www.gnu.org, or by writing to the Free Software Foundation. This document is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. History Rev Date Author Comments 1.0 20/7/2008 Nathan Yawn Initial version Contents 1.Introduction.............................................................................................................................................5 1.1.Overview.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2.Versions...........................................................................................................................................6 1.3.Stub-based methods.........................................................................................................................6 2.System Components................................................................................................................................7 -

A Pythonic Approach for Rapid Hardware Prototyping and Instrumentation

A Pythonic Approach for Rapid Hardware Prototyping and Instrumentation John Clow, Georgios Tzimpragos, Deeksha Dangwal, Sammy Guo, Joseph McMahan and Timothy Sherwood University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, 93106 USA Email: fjclow, gtzimpragos, deeksha, sguo, jmcmahan, [email protected] Abstract—We introduce PyRTL, a Python embedded hardware To achieve these goals, PyRTL intentionally restricts users design language that helps concisely and precisely describe to a set of reasonable digital design practices. PyRTL’s small digital hardware structures. Rather than attempt to infer a and well-defined internal core structure makes it easy to add good design via HLS, PyRTL provides a wrapper over a well- defined “core” set of primitives in a way that empowers digital new functionality that works across every design, including hardware design teaching and research. The proposed system logic transforms, static analysis, and optimizations. Features takes advantage of the programming language features of Python such as elaboration-through-execution (e.g. introspection), de- to allow interesting design patterns to be expressed succinctly, and sign and simulation without leaving Python, and the option encourage the rapid generation of tooling and transforms over to export to, or import from, common HDLs (Verilog-in via a custom intermediate representation. We describe PyRTL as a language, its core semantics, the transform generation interface, Yosys [1] and BLIF-in, Verilog-out) are also supported. More and explore its application to several different design patterns and information about PyRTL’s high level flow can be found in analysis tools. Also, we demonstrate the integration of PyRTL- Figure 1. generated hardware overlays into Xilinx PYNQ platform. -

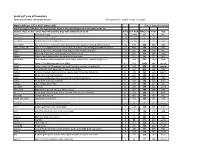

Small Soft Core up Inventory ©2019 James Brakefield Opencore and Other Soft Core Processors Reverse-U16 A.T

tool pip _uP_all_soft opencores or style / data inst repor com LUTs blk F tool MIPS clks/ KIPS ven src #src fltg max max byte adr # start last secondary web status author FPGA top file chai e note worthy comments doc SOC date LUT? # inst # folder prmary link clone size size ter ents ALUT mults ram max ver /inst inst /LUT dor code files pt Hav'd dat inst adrs mod reg year revis link n len Small soft core uP Inventory ©2019 James Brakefield Opencore and other soft core processors reverse-u16 https://github.com/programmerby/ReVerSE-U16stable A.T. Z80 8 8 cylcone-4 James Brakefield11224 4 60 ## 14.7 0.33 4.0 X Y vhdl 29 zxpoly Y yes N N 64K 64K Y 2015 SOC project using T80, HDMI generatorretro Z80 based on T80 by Daniel Wallner copyblaze https://opencores.org/project,copyblazestable Abdallah ElIbrahimi picoBlaze 8 18 kintex-7-3 James Brakefieldmissing block622 ROM6 217 ## 14.7 0.33 2.0 57.5 IX vhdl 16 cp_copyblazeY asm N 256 2K Y 2011 2016 wishbone extras sap https://opencores.org/project,sapstable Ahmed Shahein accum 8 8 kintex-7-3 James Brakefieldno LUT RAM48 or block6 RAM 200 ## 14.7 0.10 4.0 104.2 X vhdl 15 mp_struct N 16 16 Y 5 2012 2017 https://shirishkoirala.blogspot.com/2017/01/sap-1simple-as-possible-1-computer.htmlSimple as Possible Computer from Malvinohttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prpyEFxZCMw & Brown "Digital computer electronics" blue https://opencores.org/project,bluestable Al Williams accum 16 16 spartan-3-5 James Brakefieldremoved clock1025 constraint4 63 ## 14.7 0.67 1.0 41.1 X verilog 16 topbox web N 4K 4K N 16 2 2009 -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Minimizing Leakage Energy in FPGAs Using Intentional Post-Silicon Device Aging Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/75h4m6qb Author Wei, Sheng Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California Los Angeles Minimizing Leakage Energy in FPGAs Using Intentional Post-Silicon Device Aging A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Computer Science by Sheng Wei 2013 c Copyright by Sheng Wei 2013 Abstract of the Thesis Minimizing Leakage Energy in FPGAs Using Intentional Post-Silicon Device Aging by Sheng Wei Master of Science in Computer Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Miodrag Potkonjak, Chair The presence of process variation (PV) in deep submicron technologies has be- come a major concern for energy optimization attempts on FPGAs. We develop a negative bias temperature instability (NBTI) aging-based post-silicon leakage energy optimization scheme that stresses the components that are not used or are off the critical paths to reduce the total leakage energy consumption. Further- more, we obtain the input vectors for aging by formulating the aging objectives into a satisfiability (SAT) problem. We synthesize the low leakage energy designs on Xilinx Spartan6 FPGA and evaluate the leakage energy savings on a set of ITC99 and Opencores benchmarks. ii The thesis of Sheng Wei is approved. Jason Cong Milos Ercegovac Miodrag Potkonjak, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2013 iii Table of Contents 1 Introduction :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 2 Related Work ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.1 Process Variation . -

Evaluation of Synthesizable CPU Cores

Evaluation of synthesizable CPU cores DANIEL MATTSSON MARCUS CHRISTENSSON Maste r ' s Thesis Com p u t e r Science an d Eng i n ee r i n g Pro g r a m CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Depart men t of Computer Engineering Gothe n bu r g 20 0 4 All rights reserved. This publication is protected by law in accordance with “Lagen om Upphovsrätt, 1960:729”. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the authors. Daniel Mattsson and Marcus Christensson, Gothenburg 2004. Evaluation of synthesizable CPU cores Abstract The three synthesizable processors: LEON2 from Gaisler Research, MicroBlaze from Xilinx, and OpenRISC 1200 from OpenCores are evaluated and discussed. Performance in terms of benchmark results and area resource usage is measured. Different aspects like usability and configurability are also reviewed. Three configurations for each of the processors are defined and evaluated: the comparable configuration, the performance optimized configuration and the area optimized configuration. For each of the configurations three benchmarks are executed: the Dhrystone 2.1 benchmark, the Stanford benchmark suite and a typical control application run as a benchmark. A detailed analysis of the three processors and their development tools is presented. The three benchmarks are described and motivated. Conclusions and results in terms of benchmark results, performance per clock cycle and performance per area unit are discussed and presented. Sammanfattning De tre syntetiserbara processorerna: LEON2 från Gaisler Research, MicroBlaze från Xilinx och OpenRISC 1200 från OpenCores utvärderas och diskuteras. -

BCS OSSG Newsletter July 2011 Page 1 of 8 Figure 1: Overall Design of the Openrisc 1200

Open Source Software Meets Open Source Hardware: The OpenRISC 1000 Jeremy Bennett, Embecosm Abstract This paper presents the OpenRISC 1200, an open source implementation of the OpenRISC 1000 architecture, verified using open source tools. The OpenRISC 1000 is supported by a modern GNU tool chain and is capable of running Linux as well as many real-time operating systems. 1 Introducing the OpenRISC 1000 Architecture The OpenRISC 1000 architecture defines a family of 32 and 64-bit RISC processors with a Harvard architecture [9]. The instruction set architecture (ISA) is similar to that of MIPS or DLX, offering 32 general purpose registers. The processor offers WishBone bus interfaces for instruction and memory access with IEEE 1149.1 JTAG as a debugging interface. Memory management units (MMU) and caches may optionally be included. The core instruction set features the common arithmetic/logic and control flow instructions. Optional additional instructions allow for hardware multiply/divide, additional logical instructions, floating point and vector operations. The ALU is a 4/5 stage pipeline, similar to that in early MIPS designs. A hardware debug unit provides access to all registers and main memory and allows external stall/unstall and reset of the processor via JTAG. This interface can be used to provide software debug access via the GDB remote serial protocol. One particularly useful feature is the parameterized NOP instruction, l.nop. The 16-bit immediate operand is ignored by hardware, but can be used by simulators to provide useful side-effects, such as host I/O and tracing. The design is completely open source, licensed under the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL), this means it can be included as an IP block in larger designs, without requiring that the rest of the design be open source. -

A Survey of FPGA Benchmarks

A Survey of FPGA Benchmarks A Survey of FPGA Benchmarks Raphael Njuguna, [email protected] (A project report written under the guidance of Prof. Raj Jain) Download Abstract New markets are emerging for the fast growing field-programmable gate array (FPGA) industry. Standard and fair benchmarking practices are necessary to evaluate FPGA systems and determine their potential to support target applications. This paper provides an extensive survey of FPGA benchmarks in both academia and industry. Keywords: FPGA, Benchmark, Performance, Evaluation, RAW, VPR, MCNC, IWLS, PREP, Toronto 20, LINPACK, DSP, BDTI, MATLAB, MediaBench, OpenFPGA, Smith-Waterman, BLAST, EEMBC, Dhrystone, MiBench, OpenCores. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Historical Background 3. Benchmarks for Traditional FPGA Systems 3.1. RAW Benchmark Suite 3.2. VPR Benchmark 3.3. MCNC Benchmark suite 3.4. IWLS 2005 Benchmarks 3.5. PREP Benchmark Suite 3.6. Toronto 20 Benchmark suite 3.7. LINPAC Benchmark 4. Benchmarks for Hybrid-FPGA Systems 4.1. Benchmarks for FPGA-based Digital Signal Processing Systems 4.1.1. BDTI Communications Benchmark 4.1.2. MATLAB Benchmarks 4.1.3. MediaBench Benchmark Set 4.2. Benchmarks for FPGA-based Biological Systems 4.2.1. OpenFPGA.org 4.2.2. Smith-Waterman Algorithm 4.2.3. BLAST 4.3. Benchmarks for FPGA-based Embedded Systems 4.3.1. EEMBC Benchmarks 4.3.2. Dhrystone Benchmark 4.3.3. MiBench Benchmark Suite 5. Sources of FPGA Benchmarks 5.1. Conference Benchmarks 5.2. Open Source Benchmarks 5.3. Synthetic Benchmarks 1 of 13 A Survey of FPGA Benchmarks 5.4. Industrial Benchmarks 6. Summary 7. -

Development of an Application for Wupper a Pcie Gen3 DMA for Virtex 7

Electronics Technology Development of an application for Wupper a PCIe Gen3 DMA for Virtex 7 Oussama el Kharraz Alami 29-1-2016 Studentnumber: 500639457 Course: Bachelor's Degree, Electrical Electronic and Communications Engineering School: Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences Supervisors: Andrea Borga, Nikhef, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Frans Schreuder, Nikhef, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Wim Dolman, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. WUPPER Science Park 105 - 1098XG Amsterdam Development of an application for Wupper a PCIe Gen3 DMA for Virtex 7 Contents 1 Introduction3 1.1 Wupper package...............................3 2 Internship4 2.1 Goal.....................................4 2.2 Topics....................................4 2.3 Drivers and tools...............................4 2.4 VHDL example application code.......................4 2.5 Developing a GUI..............................4 3 Wupper package5 3.1 Wupper core.................................5 3.1.1 Xilinx PCIe End Point........................6 3.1.2 Core control.............................6 3.1.3 DMA read/write...........................7 3.2 Example application HDL modules.....................7 3.2.1 Functional blocks..........................7 3.3 Device driver and Wupper tools....................... 10 3.3.1 Operating Wupper-dma-transfer................... 11 3.3.2 Operating Wupper-chaintest..................... 13 3.4 Wupper GUI................................. 14 3.4.1 Functional blocks and threaded programming............ 14 -

Open Source Business Models

OPEN SOURCE BUSINESS MODELS David Ma Blaney McMurtry LLP 416.596.2895 [email protected] OPEN SOURCE BUSINESS MODELS by David Ma1 1. INTRODUCTION This paper will: (a) review some of the more common business models used to exploit intellectual property; (b) describe, in brief, what open source is; and (c) identify characteristics of open source licenses as they pertain to those business models. It is oriented primarily to owners or developers of intellectual property that are contemplating the alternatives available to them in the commercial exploitation of that IP. The general context on which this paper focuses is the development and exploitation of software. However, some or all of the principles described below may be applied in other contexts, and we describe some of these briefly toward the end of the paper. The intent of this paper is not to advocate open source business models as the definitive way to undertake such a venture. Rather, it is to familiarize the reader with the underpinnings of what is becoming an increasingly prevalent approach to exploiting IP which warrants serious consideration as an alternative to more traditional methods ‐ namely, a proprietary licensing model which emphasizes the treatment of underlying source code as a trade secret. It may well be that the particular circumstances of a business undertaking do not lend themselves to such models. However, it would be, in the author’s opinion, inadvisable not to give them due consideration. 2. WHAT IS OPEN SOURCE? Perhaps the key principle of the open source is denial ‐ more specifically, denying any one person the right to exclusively exploit software. -

FPGA to ASIC Comparison Details

book 4/9/2009 16: 24 page 133 Appendix A FPGA to ASIC Comparison Details This appendix provides information on the benchmarks used for the FPGA to ASIC comparisons in Chap. 3. As well, some of the absolute data from that comparison is provided; however, area results are not included as that would disclose confidential information. A.1 Benchmark Information Information about each of the benchmarks used in the FPGA to ASIC comparisons is listed in Table A.1. For each benchmark, a brief description of what the benchmark does is given along with information about its source. Most of the benchmarks were obtained from OpenCores (http://www.opencores.org/) while the remainder of the benchmarks came from either internal University of Toronto projects [29, 71, 165, 166] or external benchmark projects at http://www.humanistic.org/∼hendrik/reed- solomon/index.html or http://www.engr.scu.edu/mourad/benchmark/RTL-Bench. html. As noted in the table, in some cases, the benchmarks were not obtained directly from these sources and, instead, were modified as part of the work performed in [79]. The modifications included the removal of FPGA vendor-specific constructs and the correction of any compilation issues in the designs. A.2 FPGA to ASIC Comparison Data The results in Chap. 3 were given only in relative terms. This section provides the raw data underlying these relative comparisons. TablesA.2 andA.3 list the maximum operating frequency and dynamic power, respectively, for each design for both the FPGA and ASIC. Finally, Tables A.4 and A.5 report the FPGA and ASIC absolute static power measurements for each benchmark at typical- and worst-case conditions, respectively. -

OP2P Interface IP Core Datasheet

OP2P Interface IP Core Datasheet Istvan Nagy 2011 www.opencores.org [email protected] Description: Open Peer to Peer Interface, Wishbone to Aurora Bridge (OP2P). This IP core is only one port. It implements a higher (transaction) layer of the communication stack, while the lower (physical) layer is implemented inside the Xilinx Aurora interface IP (using various types of the Xilinx multi-gigabit serial transceivers) generated in the Xilinx CoreGenerator program. The OP2P interface was developed to provide a low latency, low software- overhead board-to-board communication interface. It is basically a “Buffer-Copy” interface; it copies data from a DRAM memory buffer on one board to a memory buffer on another board, initiated by a command which specifies the address locations within both the source and the target buffers. The buffers should be memory mapped within the system address spaces of the boards independently (PCI/PCIe devices). It is based on PCI-express, with certain modifications: all ports are non-transparent and peer- to-peer supports packet forwarding in indirect mesh connections without the on-board system processor’s (usually X86 high performance processor like Intel Core-x, Xeon…) intervention. This is called distributed switching; no switch cards are needed in the system/network. The system or network can be backplane-based or cable-based, or a mixture of them. There are similarities with PCI-express in the way of handling the packets, but without the limitation of the master-slave relationships. There are also similarities with Ethernet, without the excessive software overhead and the limitations of the link-width and speed inflexibility. -

Small Soft Core up Inventory Opencore and Other Soft Core Processors Only Cores in the "Usable" Category Included

Small soft core uP Inventory Opencore and other soft core processors Only cores in the "usable" category included Highest KIPS per LUT or ALUT (above 200) ©2014 James Brakefield Work in progress: KIPS/LUT only approximate, many of the small designs will move down on the list Caution: these are bare cores, Fmax will probably drop with additional LUT count wd sz LUT-ALUT KIPS/LUT Fmax style cray1 homebrew Cray1 64 13463 57 127 RISC fpgammix clone of Knuth's MMIX 64 11605 3 94 RISC s1_sparc reduced version of OpenSPARC T1 64 52485 2 56 RISC microblaze Xilinx propretary, area optimized, 70 configuration options, fltg-pt & MMU optional 32 546 603 320 RISC ARM_Cortex_A9 ASIC, LUTs number based on relative area, dual issue, includes fltg-pt & MMU & caches 32 4500 583 1050 RISC nios2 Altera proprietary, speed optimized, fltg-pt, cache & MMU optional 32 895 390 310 RISC hive 4-8 symetrical stacks, eight threads via pipeline barrel 32 905 313 284 stack mblite clone of microblaze, not all instructions implemented 32 941 241 227 RISC microcore Forth machine with indexing into return stack, auto inc/dec, variable length imm 32 644 231 149 stack leros Leros: A Tiny Microcontroller for FPGAs 16 112 1089 182 accum Lutiac Lutiac – Small Soft Processors for Small Programs (academic paper only) 16 140 948 198 register iDEA The iDEA DSP Block Based Soft Processor for FPGAs 16 321 845 405 RISC octavo Octavo: an FPGA-Centric Processor Family, eight thread barrel pipeline 16 500 737 550 register cpu16 16-bit forth machine, 5-bit inst 16 367 648 355 forth xr16