Copy of Bcp 18112011 English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banni Grassland

Symposium on Banni Grassland Report of Symposium on Banni Grassland 4th & 5th March 2011 Symposium Sponsors Gujarat State Forest Department, GoG, Gandhinagar Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation, GoG, Gandhinagar Commissionerate of Rural Development, GoG, Gandhinagar Organized By Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE) Post Box # 83, Mundra Road Bhuj – 370 001, Kachchh, Gujarat, India Website: www.gujaratdesertecology.com Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE), Bhuj-Kachchh Symposium on Banni Grassland Background Banni region has a very fascinating history, geography, diversity of flora and fauna, highly nutritive grasses; rich cultural heritage of Maldhari (Cattle breeders) communities, unrivalled embroidery work and other handicrafts, soul-touching folk and Sufi music, earthquake resistant mud houses Bhunga, traditional fresh water reservoirs Virda, traditional knowledge of medicinal plants and animal breeding and last but never the least, drought tolerant highly productive livestock - the very base of survival of Maldharis. Banni is perhaps the only largest stretch (2617 km2) of grasslands in India, which was once the „finest grassland‟ of Asia. It is located between Kachchh mainland and Greater Rann of Kachchh in the north western part of Gujarat State of India. The region is believed to have formed due to seismic activities and marine processes operating in the north along with fluvial deposition by the Indus and other rivers during the Vedic times. These virtues of Banni have always attracted scientists, sociologists, naturalists and tourists. Livestock is the mainstay of inhabitants of Banni, constituting major bulk of their assets. Despite tough survival conditions, Banni buffaloes are the most productive cattle in India and are recently recognised by „National bureau of Animal Genetic Resources‟ as 11th distinct breed of the nation. -

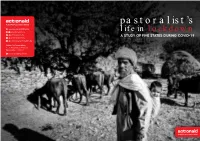

Pastoralist's Life in Lockdown

pastoralist’s www.actionaidindia.org @actionaidindia life in lockdown @actionaid_india A STUDY OF FIVE STATES DURING COVID-19 @actionaidcomms @company/actionaidindia ActionAid Association, R - 7, Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi - 110016 +911-11-4064 0500 2 3 Pastoralist’s Life in Lockdown A study of five States during COVID-19 Pastoralist’s Life in Lockdown A study of five States during COVID-19 First Published September, 2020 Some rights reserved This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Provided they acknowledge the source, users of this content are allowed to remix, tweak, build upon and share for non- commercial purposes under the same original license terms. Photograph Credits Anu Verma and Biren Nayak Edited by Joseph Mathai Layout by M V Rajeevan Cover Page by Nabajit Malakar Published by Natural Resources Knowledge Activist Hub www.actionaidindia.org @actionaidindia @actionaid_india @actionaidcomms @company/actionaidindia ActionAid Association R - 7, Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi - 110016 +911-11-4064 0500 Printed at: Baba Printers, Bhubaneswar CONTENTS Foreword v Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Understanding pastoralism and pastoral occupation 3 Pastoral communities in India 7 Chapter 2: Impact of COVID-19 on Pastoralists: An Overview 11 Methodology 14 Chapter 3: Study Findings 17 Challenges in moving with herd during lockdown 17 Changes in time of migration 19 Mobility of pastoral communities during lockdown 22 Change in -

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited Toll Free : 1800 200 5080 | www.gujarattourism.com Designed by Sobhagya Why is Gujarat such a haven for beautiful and rare birds? The secret is not hard to find when you look at the unrivalled diversity of eco- Merry systems the State possesses. There are the moist forested hills of the Dang District to the salt-encrusted plains of Kutch district. Deciduous forests like Gir National Park, and the vast grasslands of Kutch and Migration Bhavnagar districts, scrub-jungles, river-systems like the Narmada, Mahi, Sabarmati and Tapti, and a multitude of lakes and other wetlands. Not to mention a long coastline with two gulfs, many estuaries, beaches, mangrove forests, and offshore islands fringed by coral reefs. These dissimilar but bird-friendly ecosystems beckon both birds and bird watchers in abundance to Gujarat. Along with indigenous species, birds from as far away as Northern Europe migrate to Gujarat every year and make the wetlands and other suitable places their breeding ground. No wonder bird watchers of all kinds benefit from their visit to Gujarat's superb bird sanctuaries. Chhari Dhand Chhari Dhand Bhuj Chhari Dhand Conservation Reserve: The only Conservation Reserve in Gujarat, this wetland is known for variety of water birds Are you looking for some unique bird watching location? Come to Chhari Dhand wetland in Kutch District. This virgin wetland has a hill as its backdrop, making the setting soothingly picturesque. Thankfully, there is no hustle and bustle of tourists as only keen bird watchers and nature lovers come to Chhari Dhand. -

The King's Last Fight

ZOOLOGY 76 The King’s last fight Once the realm of the Asiatic lion stretched from the Mediterranean to Central Asia. Today its habitat has shrunk to a small protected area in north-west India. Although it is thriving there, the species is not yet out of the woods PHOTOS: BRENT STIRTON/GETTY IMAGES BRENT STIRTON/GETTY PHOTOS: Words: Fabian von Poser Photography: Brent Stirton 77 78 ZOOLOGY At the beginning of the 20th century there were only a mere 20 to 40 lions. After that the population recovered slowly. The last census in 2010 revealed a population of 411 79 ZOOLOGY 80 From their ambush lions attack with lightning speed. The herdsmen of the region have learned to live with the losses, even if it hurts: a cow or a buffalo is worth 500 euros, a small fortune in India 81 ZOOLOGY N THE EARLY MORNING it is still cool Once the king of beasts ruled a vast territory that in Gir. Slowly the heat of the incipient day stretched from the Mediterranean to India. Just 150 I dissolves the fog in the treetops. The morning years ago the big cats crossed through the steppes sun illuminates the forest honey yellow. Against of the Middle East and Central Asia. But man’s the first light of day the teak trees appear as in a relentless hunting brought them to the edge of whimsical painting. It is quiet, only the shrill call extinction. In Turkey, the last lion was shot in 1870, of the peacocks penetrates the forest. At a water in Syria in 1895, in Iraq in 1918. -

Maldhari' and the Gir Prctected Area - Amufualinteraction

RJPSS 40, No.2,2015 3t 'Maldhari' and the Gir Prctected Area - Amufualinteraction 5 Dr. Rajeshwarsinh N Chudasama* Introduction: The most important human component ofthe Gir ecosystem has been the population ofresident 'Maldhari'. They are devoutly religious pastoral community who has been an integral part of Gir forest for generations. They are living in about 54 small settlements called 'Nesses' in the forest area with atotal human population of 2,540 and that of cattle about 9,820. They are physically robust, courageous and amiable persons. They live on purely vegetarian diet. Sale of dairy products has always been the mainstay of their economy. They earn their livelihood by selling milk and ghee (clarified butter) in the nearby towns and also supplement their income by selling dung manure. Their domestic livestock comprised mainly ofbuffaloes and cows, though they also possess camels which ane mainly used for tansport and as beasts ofburden. Their animals are kept together during night in circular thorn fencing known as 'Zok' and are let loose into the surrounding forests for grazing throughout the day. I)ependence of Maldhari on Protected Area: The following areas are identified in terms of dependence of maldhari on the protected area. Livestock Feeding: The livestock of maldhari are fully dependent on the protected area for green and dry fodder. The animals graze throughout the year. However, ttre availability of green grass is limited to only monsoon season and initial part of winter season. For rest of the year, the animals have to depend on dry grass. The availability of even dry grass becomes very limited duringthe summerwhich is stored forthe use during summer.In addition to feeding of grasses to their animals, they also provide some concentrate feeds like cottonseed and cottonseed cakes to their animals. -

Intersection of Ecology and Culture in Pastoral Landscape Banni Grassland .Kutch

Life of a Maldhari (Banni Pastoralist) “ When the land is discarded and the world called it as ‘waste’… When life is harsh and the extremities are the realities…. When the climate changes and hope remains, yet another day to survive persists, in search of grass heads held high, hearts tied to their cattle… a day dawns into another defining, the edges of landscape and traditions of the life….” Intersection of Ecology and Culture in Pastoral Landscape Banni Grassland .Kutch. India Jagadeesh Gorle Vandana Sreepada Divya Shah Camel Banni Horse Bunni Buffalo Kankrej Bull Goat Sheep Dromedary Equus caballus Bubalus bubalis Bos taurus indicus Capra aegagrus circus Ovis aries Nano Zinzvo Madhanu Khevai Sewan Dhaman Cenchrus Oin Cenchrus Dichanthium Cenchrus Eragrostis Eleusine Sporobolus setigerus cillaris Lasiurus helvolus annulatum Cressa cretica sindicus setigerus variablilis Indica Dhrab Chhabra Dhrabad Shiyal puch Desmotachya Cynodon Cynodon Chloris Chloris Suaeda Sporobolus Eragrostis bipinnata dactylon Eleusine Celianensis dactylon barbata barbata fruticosa diand&r Echinochloa Chiyo Madhanu Khariyu Kal Dactyloctenium Echinochloa Eleusine Cyperus Sachhurum Dactyloctenium Aeluropus aegyptium Sporobolus Eragrostis Colona Indica rotundus sindicum lagopoides Scirpus sps. spp Kutch Peninsula and Banni Grassland Half gabrion formation of Banni Grassland between Rann of Kutch Grass diversity and the Pastoral breeds developed by the local hereders in response and Bhuj Ridge with the land over generations Land in its Dynamic nature reflects in the -

1 Gggg Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge

gg1 Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Azim Premji University 2019-2020 gg 12 Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Azim Premji University Modern India has a history of a vibrant and active social sector. Many local development organisations, community organizations, social movements and non-governmental organisations populate the space of social action. Such organisations imagine a different future and plan and implement social interventions at different scales, many of which have lasting impact on the lives of people and society. However, their efforts and, more importantly, the learning from these initiatives remains largely unknown not only in the public sphere but also in the worlds of ‘development practice’ and ‘development education’. This shortfall impedes the process of learning and growth across interventions, organizations and time. While most social sector organizations acknowledge this deficiency in documentation and knowledge creation, they find themselves strapped for time and motivation to embark on such efforts. Writing with a sense of reflection and self-analysis which goes beyond mere documentation and creates a platform for learning requires time and space. As a result, their writing is usually limited to documentation captured in grant proposals or project updates or ‘good practices’ literature with inadequate focus on capturing the nuances, boundaries and limitations of action. Recognizing this need, the Azim Premji University launched ‘Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge’ with the objective of encouraging social sector organisations to invest in developing a grounded knowledge base for the sector. We are delighted to report that in the inaugural year of this challenge (2018 – 19) we received 95 cases, covering interventions from education, sustainability, livelihoods, preservation of culture and community health. -

The Maldhari Touch to Kutchi Performing Arts (The Kutch Maldhari Lok-Kala Mahotsava, Bhuj, February 22-27, 1983)

The Maldhari Touch to Kutchi Performing Arts (The Kutch Maldhari Lok-kala Mahotsava, Bhuj, February 22-27, 1983) Mohan Nadkarni A vast tract of land, exposed since time immemorial to the vagaries of the elements-that is Kutch, a region bound by the Gulf of Kutch on the south, the Arabian Sea on the west and separated from the mainland by the 8,000 square miles of the Rann of Kutch on the north and the east. Geographically speaking, the Kutch territory, often mentioned as Ahir Desha in ancient literature, is one of the most segregated areas of the State of Gujarat as it is constituted today. With an annual rainfall of only 400 millimetres, the territory is arid. The climate, though, is conducive to cultivation of grass to feed cattle. The history of Kutch is traced to the Harappan period of the Indus Valley Civilization. On the basis of available data, it would appear that Kutch had a riverine culture since the Indus once flowed through the region. The Harappans, it would seem, had found this region suitable for the development of agriculture and animal husbandry. Through the centuries, however, Kutch gradually became a land of immigrants, who came from Sind, Rajasthan and Kathiawad (Saurashtra). It is now inhabited by several nomadic tribes and communities such as Ahirs, Rabaris, Bharwads, Langas, Kalis, Charans and Kheduts. It is also a region where a large number of Hindus and Muslims, known as Maldharis, live in complete harmony. So much so, that there has not been a single instance of communal rioting anywhere in Kutch . -

Embroidered Relations in Kutch: Women, Stitching and the Third Space

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2012 Embroidered Relations in Kutch: Women, Stitching and the Third Space Michele A. Hardy University of Calgary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Hardy, Michele A., "Embroidered Relations in Kutch: Women, Stitching and the Third Space" (2012). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 693. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/693 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Embroidered Relations in Kutch: Women, Stitching and the Third Space Michele A. Hardy [email protected] Dhordo is a tiny village located in northern Kutch and the site of my ongoing investigation into the history of embroidery. It is the home to the Mutwa—whose intricate mirror-studded embroidery has been widely praised, is represented in international museum collections and has been featured in numerous exhibitions and publications.1 But Mutwa embroidery is also simultaneously distinctive and backward, changing and degraded, exotic and quotidian. This paper examines these contradictions in light of Homi Bhabha’s notions of third space in order to better understand the relationship between Mutwa women, embroidery and identity. While Bhabha’s theories have been widely influential their usefulness for articulating the subtle politics of textiles and identity have not yet been fully explored. -

Report of the Community Conservation Resilience Initiative in India Country Report on India Community Conservation Resilience Initiative (CCRI) June 2018

Report of the Community Conservation Resilience Initiative in India Country report on India Community Conservation Resilience Initiative (CCRI) June 2018 Authors: Souparna Lahiri (Part 1, Buxa-Chilapata and Tadoba Andhari), Swati Shresth (Part 2, Pastoral community of Banni Grasslands) Assessment facilitation: All India Forum of Forest Movements (Buxa-Chilapata and Tadoba Andhari) and Sahjeevan (Banni Grasslands) For more information: http://globalforestcoalition.org/resources/supporting-community-conservation/ Cover photo: Livestock in the Banni Grasslands. Swati Shresth/GFC The production of this country report has been made possible thanks to the support of the Christensen Fund and the German International Climate Initiative (IKI). The German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) supports this initiative on the basis of a decision adopted by the German Bundestag. The participatory community assessments reflected in this report have been made possible thanks to the community members themselves, xxxx, and The Christensen Fund. Disclaimer: The information contained in the case studies in this report has been provided by the national group responsible. As such, the report does not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of GFC, its donors or other contributors. © Global Forest Coalition, June 2018 Community Conservation Resilience Initiative in India Part 1: Buxa-Chilapata and Tadoba Andhari Part 2: Pastoral community of Banni grassland 1 Part 1: Forests and Forest Communities in India: CCRI assessments in Buxa- Chilapata and Tadoba Andhari India is home to a billion people and represents a wide spectrum of biological, cultural and geographic diversity. The confluence of the Indo-Malayan, the Eurasian and the Afro- Tropical biogeographic zones makes India extremely biodiverse in its genes, species and ecosystems. -

Traditional Conservation of Buffalo Breed by Pastoralists Through Maintaining of Grassland Ecosystem, Banni-Kachchh, Gujarat- India

University of Kentucky UKnowledge International Grassland Congress Proceedings XXIII International Grassland Congress Traditional Conservation of Buffalo Breed by Pastoralists through Maintaining of Grassland Ecosystem, Banni-Kachchh, Gujarat- India P. N. Joshi Sahjeevan, India Ramesh Bhatti Sahjeevan, India Sabyasachi Das Sahjeevan, India Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc Part of the Plant Sciences Commons, and the Soil Science Commons This document is available at https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc/23/3-5-1/9 The XXIII International Grassland Congress (Sustainable use of Grassland Resources for Forage Production, Biodiversity and Environmental Protection) took place in New Delhi, India from November 20 through November 24, 2015. Proceedings Editors: M. M. Roy, D. R. Malaviya, V. K. Yadav, Tejveer Singh, R. P. Sah, D. Vijay, and A. Radhakrishna Published by Range Management Society of India This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant and Soil Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Grassland Congress Proceedings by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paper ID: 1553 Theme 3. Sustainability of grasslands- social and policy issues Sub-theme 3.5. Policy issues related to sustainable grassland production Traditional conservation of Buffalo Breed by pastoralists through maintaining of grassland ecosystem, Banni-Kachchh, Gujarat-India P.N. Joshi, Ramesh Bhatti*, Sabyasachi Das SAHJEEVAN, Bhuj,Gujarat Corresponding author e-mail : [email protected] Keywords : Grassland, Institution, Pastoralists Introduction Banni region, situated at 23019’N to 23052’N to 68056’E to70032’E, comprises around 25,00 sq.km area under Bhuj taluka of Kutch district of Gujarat state, is home of Muslim nomadic pastoralists and Meghwal Hindus. -

Modeling the Economics of Grassland Degradation in Banni, India, Using System Dynamics

Modeling the Economics of Grassland Degradation in Banni, India, using System Dynamics Mihir Mathur, Kabir Sharma The Energy and Resources Institute Darbari Seth Block, IHC Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi - 110 003, INDIA Tel. (+91 11) 2468 2100 and 41504900 Fax (+91 11) 2468 2144 and 2468 2145 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Research Funded by Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India Abstract This is a study on the interactions between the grassland, livestock, the invasive species Prosopis juliflora and the economy of the Banni grasslands, located in the district of Kachchh, Gujarat, India. The study focuses on modeling grassland degradation of Banni from 1992-2015 and simulates future scenarios up to 2030 using system dynamics modeling. An economic valuation of Banni’s economy is done by discounting the future earnings of the pastoral economy (milk, livestock sale, dung manure) and charcoal economy under two scenarios 1) Base case (Business as Usual), i.e. keeping things as they stand today and 2) Prosopis Removal Policy (PRP) i.e. where a decision is implemented to remove Prosopis from Banni. Under the BAU scenario, modeling results indicate that the Banni grassland is headed for severe fodder scarcity due to shrinking area under grassland. If PRP is implemented then Banni would be able to revive its grasslands and more than double the Present Value of future earnings, up to 2030. If the policy decision to remove Prosopis is delayed by 5 years then it results into a 30% reduction in earnings indicating the policy’s time sensitivity.