Insead Faculty & Research Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teamplayers2016.Pdf

Concierge Centers Our state-of-the-art Concierge Centers welcomes our clients 7 days a week, NEW YORK · LOS ANGELES · MIAMI providing personalized assistance by our multilingual staff ( es - it - de - fr - pt - ar ) New York Headquarters/ East Coast Office 33 West 46th Street New York, NY 10036, USA Located in the heart of midtown Manhattan our headquarter office recently completed its renovation with an expansion of multiple floors to house meeting space, entertainment space, Media & projection facilities. In addition a highly visible street level Concierge Center open 7 days a week to welcome our visitors. / Key Personnel Simonetta Angiolin Director of Operations Los Angeles Miami [email protected] West Coast Office Florida/Caribbean Office Sabina Pederzini 404 South Figueroa Street Los Angeles, CA 90071 1850 Collins Avenue Miami Beach, FL 33139 Director of Sales [email protected] Key Personnel /Operative Departments Information Technology FIT Teamamerica has a staff of highly qualified multi-lingual professionals dedicated to [email protected] [email protected] the service and the anticipated needs of all of our customers; and always with a Extranet Contracting smile and human touch to service our guests. [email protected] [email protected] Escorted Tours Elite [email protected] [email protected] Groups [email protected] Enzo Perretta Veronique Hubert C.E.O. C.O.O. [email protected] [email protected] Contracting Achille Minerva Josephine Cirigliano Pasquina De Carlo -

2005 Manhattan Hotel Market Overview Page 1 of 22

HVS International : 2005 Manhattan Hotel Market Overview Page 1 of 22 Manhattan Hotel Market Overview HVS International, in cooperation with New York University’s Preston Robert Tisch Center for Hospitality, Tourism, and Sports Management, is pleased to present the eighth annual Manhattan Hotel Market Overview. In 2004, the Manhattan lodging market experienced an impressive recovery, with a RevPAR increase of 22% compared to 2003. From March through December of 2004, the market recorded double-digit growth in RevPAR each month, ranging from a high of 41% in April to a low of roundly 17% in October. At 83.2%, overall occupancy reached close to the historical peak achieved in 2000 (at 83.7%) while marketwide average rate was less than 10% below the 2000 level. Occupancy and average rate in 2005 should surpass 2000 levels. Due to limited new supply and increased compression resulting from near-maximum-capacity occupancy levels, overall RevPAR will experience double-digit growth for the next few years. Based on an overall improved economic climate, strong barriers to entry, limited new supply, and increased compression, we forecast the Manhattan lodging market to achieve a robust ±17% RevPAR growth in 2005. HVS International HVS International is a global consulting and services organization focused on the hotel, restaurant, timeshare, gaming, and leisure industries. Its clients rely on the firm’s specialized industry knowledge and expertise for advice and services geared to enhance economic returns and asset value. Through a network of 23 offices staffed by more than 200 seasoned industry professionals, HVS offers a wide scope of services that track the development/ownership process. -

216 41 Cooper Square 89 Abyssinian Baptist Church 165 Alimentation 63

216 index 41 Cooper Square 89 Angel’s Share 92 The Half King Bar & Attaboy 56 Restaurant 83 A Bar 54 127 The Vig Bar 63 Bar Veloce 93 Verlaine 57 Abyssinian Baptist Bembe 173 White Horse Tavern 74 Church 165 Bemelmans Bar 147 Baseball 206 Alimentation 63, 75, 84, Blind Tiger Ale House 73 Basketball 206 93, 102, 157 d.b.a. East Village 93 Bateau 197 American Museum of Dos Caminos 102 Battery Maritime Natural History 153 Gallow Green 83 Building 46 Apollo Theater 164 Great Hall Balcony Bar 147 Battery Park 46 Appartements 184 Henrietta Hudson 74 Hudson Common 128 Battery Park City 41 Appellate Division Hudson Malone 118 Beacon Theatre 156 Courthouse of the New Jake’s Dilemma 156 York State Supreme Bedford Avenue 171 La Birreria 102 Belvedere Castle 136 Court 95 Le Bain 83 Bethesda Fountain & Argent 199 Library Bar 128 Terrace 135 Astoria 175 McSorley’s Old Ale Astor Place 88 House 93 Bijouteries 119 Auberges de Paddy Reilly’s Music Birdland 128 jeunesse 185 Bar 102 Blue Note 74 Paris Café 40 Boerum Hill 171 Autocar 183 Pegu Club 63 Bow Bridge 136 Avery Architectural & Please Don’t Tell 93 Fine Arts Library 162 Roof Garden Café and Bowery Ballroom 57 Avion 180 Martini Bar 147 British Empire Sake Bar Decibel 93 Building 109 B Schiller’s Liquor Bar 57 Broadway 120 Shalel Lounge 156 Bronx 176 Banques 199 Sky Terrace 128 Bronx Zoo 177 Bars et boîtes S.O.B.’s 63 Brookfield Place 42 de nuit 200 The Brooklyn Barge 173 68 Jay Street Bar 173 The Dead Rabbit Grocery Brooklyn 168 Abbey Pub 156 and Grog 40 Brooklyn Botanic Aldo Sohm Wine Bar 127 The -

12RFR13 Who We Are

12RFR13 Who We Are RFR has built a world-class portfolio of over 70 commercial, residential, hotel and retail properties in the United States and Germany totaling 11.5 million square feet. The portfolio includes the prized New York landmarked Seagram Building and Lever House as well as Eurotower in Frankfurt, headquarters to the European Community Bank. Our unique combination of European sophistication and American ingenuity has brought RFR to the forefront of the Real Estate industry. An experienced and cultivated team expert in acquisitions, finance, development, operations, management, leasing and sales and marketing provide RFR with the skill set to add significant value to acquired and operated properties. Our proven track record is a reflection of adding value to real estate acquired through property-level repositioning, strategic financial engineering, and two decades of experience in all phases of property life cycles and leverage opportunities. In addition, it is our commitment to add value and enrich the quality of the built environment by creating uplifting and inspiring environments, both at the building specific and urban scales. Art is an integral component in all of our properties with the display of original art by renowned artists such as Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring to name a few. We formed the Lever House Art Collection, inviting artists to create artworks specifically for the Lever House lobby for viewing by our employees, tenants and the public to enjoy. 1 1.5 million square feet worldwide Alsterarkaden Leasing Update Hamburg Germany The 300 year old Meissen Manufactory positioned as a luxury and lifestyle group dedicated to style and quality has leased 150m2 of retail space. -

RFR 285M Brochure 2016 V8.Pdf

285 Madison 285 Madison Avenue is an emblem for the emerging Bryant Park district and a vibrant mix of business tradition and innovation. An iconic pillar of the celebrated New York advertising landscape for 87 years, the 27-story building has been intelligently transformed into a contemporary office building with street presence, a striking new lobby and modern technological functionality. It is both a bridge between Grand Central and Bryant Park and a place where Midtown and Midtown South converge. Designed and engineered as a model of work/life balance, the building supports both conventional and creative enterprises, with amenities such as bike storage, a tenant lounge, outdoor space and a gym facility with showers and lockers. 285 Madison Avenue is reborn in time for Midtown’s own renaissance. Central Location 285 Madison Avenue is a strategic hub in the new Midtown, one block from the convenience of Grand Central and the world-class Bryant Park. The Park is connected to the New York Public Library, one of the city’s prized cultural assets. A short walk from 285 Madison Avenue, the Morgan Library presents fine arts, literature, film and music in a major historic site. The services of Penn Station and the energy of Times Square are also within walking distance. Grand Central Terminal Bryant Park Grand Central Terminal Metro North Railroad New York Bryant Park Public Library New York Public Library The Morgan Library New York Public The Graduate Library Center, CUNY B D Empire State F Building M Lifestyle Balance Building amenities include roof terraces, restaurant with private dining and bar, tenant lounge, gym, changing rooms, showers, lockers and bicycle storage. -

Arts in the Hotel Industry: Bridging Creative and Financial Goals for a Twenty-First Century Experience Yookyoung Kong [email protected]

Sotheby's Institute of Art Digital Commons @ SIA MA Projects Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2016 Arts in the Hotel Industry: Bridging Creative and Financial Goals for a Twenty-First Century Experience Yookyoung Kong [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_proj Part of the Arts Management Commons, Business Analytics Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Hospitality Administration and Management Commons Recommended Citation Kong, Yookyoung, "Arts in the Hotel Industry: Bridging Creative and Financial Goals for a Twenty-First Century Experience" (2016). MA Projects. 9. https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_proj/9 This MA Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Digital Commons @ SIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arts in the Hotel Industry: Bridging Creative and Financial Goals for a Twenty-First Century Experience by Yookyoung Kong A journal article in conformity With the requirements for the Master’s Degree in Art Business Sotheby’s institute of Art Presented in 2016 1. Introduction 1-1. Background and Purpose Hotels have always been more than lodging facilities; they have been recognised as places of business, public assembly, decorative showcases. Always on the forefront of technological innovation and innovative space design, they provide interesting experiences for patrons. Today, consumers seek out hotels with unique values, such as cultural and artistic features, that can enhance their trip. The hospitality landscape of cities has changed significantly in recent years: hotels are themselves destinations. -

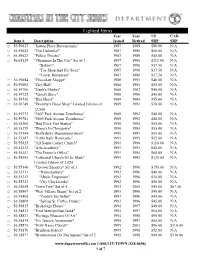

Lighted Items

Lighted Items Year Year US CAD Item # Description Issued Retired SRP SRP □ 56.59617 "Sutton Place Brownstones" 1987 1989 $80.00 N/A □ 56.59625 "The Cathedral" 1987 1990 $60.00 N/A □ 56.59633 "Palace Theatre" 1987 1989 $45.00 N/A □ 56.65129 "Christmas In The City" Set of 3 1987 1990 $112.00 N/A "Bakery" 1987 1990 $37.50 N/A "Toy Shop And Pet Store" 1987 1990 $37.50 N/A "Tower Restaurant" 1987 1990 $37.50 N/A □ 56.59684 "Chocolate Shoppe" 1988 1991 $40.00 N/A □ 56.59692 "City Hall" 1988 1991 $65.00 N/A □ 56.59706 "Hank's Market" 1988 1992 $40.00 N/A □ 56.59722 "Variety Store" 1988 1990 $45.00 N/A □ 56.59730 "Ritz Hotel" 1989 1994 $55.00 N/A □ 56.56749 "Dorothy's Dress Shop" Limited Edition of 1989 1991 $70.00 N/A 12,500 □ 56.59773 "5607 Park Avenue Townhouse" 1989 1992 $48.00 N/A □ 56.59781 "5609 Park Avenue Townhouse" 1989 1992 $48.00 N/A □ 56.55360 "Red Brick Fire Station" 1990 1995 $55.00 N/A □ 56.55379 "Wong's In Chinatown" 1990 1994 $55.00 N/A □ 56.55344 "Hollydale's Department Store" 1991 1997 $85.00 N/A □ 56.55387 "'Little Italy' Ristorante" 1991 1995 $52.00 N/A □ 56.55425 "All Saints Corner Church" 1991 1998 $110.00 N/A □ 56.55433 "Arts Academy" 1991 1993 $45.00 N/A □ 56.55441 "The Doctor's Office" 1991 1994 $60.00 N/A □ 56.55492 "Cathedral Church Of St. -

PARAMOUNT HOTEL, 235-245 West 46Th Street, Manhattan Built 1927-28; Thomas W

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 2009, Designation List 423 LP-2342 PARAMOUNT HOTEL, 235-245 West 46th Street, Manhattan Built 1927-28; Thomas W. Lamb, architect Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1018, Lot 6 On June 23, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Paramount Hotel and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 9). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were two speakers in favor of designation including a representative of the owner. There were no speakers in opposition. Summary The Paramount Hotel was constructed in 1927-28 as part of an extensive building and expansion drive in the Times Square theater district during that period. One of a very few hotels designed by noted theater architect Thomas Lamb, this building’s design reflects the theatrical nature of the neighborhood. New York in the 1920s was a popular tourist destination and this hotel was one of several built in the area that was intended to appeal to visitors coming to New York for its extensive night life. This hotel provided over 600 rooms, restaurants, lounges and a well-known nightclub in the basement. Thomas Lamb designed a large number of theaters in the area, particularly movie houses, giving them a variety of decorative treatments that suggested the fantastical interiors and variety of entertainments provided inside. Lamb was a classically- trained architect, able to use a wide-ranging architectural vocabulary geared toward the specific conditions of the building. -

New York City

8TH Ed TRAVEL GUIDE LEGEND Albany Boston Area Maps MASSACHUSETTS Providence Motorway and Poughkeepsie Interchange Hartford IA RHODE N CONNECTICUT ISLAND A NEW National Road V YORK L Y S N Highway N E P NEW Other Road JERSEY Allentown NEW YORK CITY Railway ATLANTIC The Main Dams or Philadelphia Pool OCEAN Waterways H Atlantic City ar lem River NEW YORK CITY Cape May Park Delaware Bay TRAVEL GUIDE GUIDE TRAVEL Interchange Route 278 95 46 Numbers CONTENTS Tunnel Practical, informative and user-friendly, the 1. Introducing New York City NEW YORK CITY City Globetrotter Travel Guide to New York City Town or The Land • History in Brief Long Beach Village highlights the major places of interest, describing their Government and Economy • The People Liberty Place of Island Interest principal attractions and offering sound suggestions 2. Lower Manhattan Airports on where to tour, stay, eat, shop and relax. The Best of Lower Manhattan Other Museums and Places of Interest T Toll Station The Civic Center and South Street Seaport Town Plans THE AUTHOR 3. Lower East Side and East Village Motorway and Michael Leech first visited New York City on airforce leave Lower East Side • East Village Interchange from Canada, returning to live there during the 1970s. 4. Greenwich Village, Fifth Ave Main Road Now based in central London, he travels to New York City SoHo and TriBeCa W 53rd St Other Road Greenwich Village • SoHo • TriBeCa MALL Mall every year. He has written over 30 books, and 5. Chelsea and Gramercy Park Railway extensively on North America for magazines including Sights to See • Old Residential Districts Monorail Hello and Essentially America. -

RFR 285M Commercial Broch

285 Madison 285 Madison Avenue is an emblem for the emerging Bryant Park district and a vibrant mix of business tradition and innovation. An iconic pillar of the celebrated New York advertising landscape for 87 years, the 27-story building has been intelligently transformed into a contemporary office building with street presence, a striking new lobby and modern technological functionality. It is both a bridge between Grand Central and Bryant Park and a place where Midtown and Midtown South converge. Designed and engineered as a model of work/life balance, the building supports both conventional and creative enterprises, with amenities such as bike storage, a tenant lounge, outdoor space and a gym facility with showers and lockers. 285 Madison Avenue is reborn in time for Midtown’s own renaissance. Central Location 285 Madison Avenue is a strategic hub in the new Midtown, one block from the convenience of Grand Central and the world-class Bryant Park. The Park is connected to the New York Public Library, one of the city’s prized cultural assets. A short walk from 285 Madison Avenue, the Morgan Library presents fine arts, literature, film and music in a major historic site. The services of Penn Station and the energy of Times Square are also within walking distance. Grand Central Terminal Bryant Park Grand Central Terminal Metro North Railroad New York Bryant Park Public Library New York Public Library The Morgan Library New York Public The Graduate Library Center, CUNY B D Empire State F Building M Lifestyle Balance Building amenities include roof terraces, restaurant with private dining and bar, tenant lounge, gym, changing rooms, showers, lockers and bicycle storage. -

New York, NY Hotel Descriptions

New York, NY Hotel Descriptions Algonquin Hotel 59 West 44th Street Indulge in a true 4-star experience at the Algonquin Hotel. With a picture-perfect location in Midtown Manhattan, NYC, steps away from the excitement of Times Square, our hotel makes it easy to explore world-famous landmarks. Our history of providing first-class service to influential guests makes us the perfect destination for a one-of-a-kind romantic getaway to NYC. Our historic hotel is overflowing with 4-star amenities, such as a fully stocked fitness center, free Wi-Fi access in all hotel rooms and public areas and exquisite American dining at our signature Round Table Restaurant. Host your event here in Midtown Manhattan to enjoy almost 5,000 square feet of stylishly appointed venue space and a convenient location in the heart of the city. We're moments from a variety of renowned attractions, including Bryant Park, Rockefeller Center and the Theater District. Discover unparalleled historic grandeur at The Algonquin Hotel Times Square, Autograph Collection. Candlewood Suites Times Square 339 West 39th Street Candlewood Suites Times Square has the perfect location for Extended Stay business and leisure travelers. Our NYC hotel is convenient to the major businesses in Times Square and the attractions of New York City. Our Times Square address places us within walking distance of the Jacob Javitz Convention Center, Madison Square Garden, Penn Station, Port Authority, Hudson yard, Ernst & Young, New York Times Building and Amazon among others. Our All-Suite hotel offers a comfortable work space and free high-speed internet access. -

337,864 1,129,450 3 New Stores 89,206

TIMES SQUARE | NOVEMBER 2019 KEY INDICATORS November By the Numbers Monthly Key Economic Indicators 1,129,450 Broadway attendees 337,864 Average daily pedestrian count in Times Square 89,206 Total SF leased in Times Square On November 1, Times Square Alliance unveiled the Show Globes exhibition to pay tribute to the creativity of Broadway design- 3 new stores ers and the power of live theatre. Opened in Times Square Average Daily Visitors Pedestrian Count Pedestrian counts dropped slight- ly from October to November. AVERAGE DAILY 2019 PEDESTRIAN COUNT 2018 This month, the average daily pe- 450,000 destrian count was 337,864, a 425,000 10.7% decrease from Novem- 402,759 400,000 ber 2018. 378,454 375,000 366,695 350,000 On Friday, November 1, tem- 337,864 peratures and pedestrian counts 325,000 reached their peaks at 72 de- 300,000 grees and 391,863 people. 275,000 250,000 225,000 OCTOBER NOVEMBER Source: Springboard TIMESTIMES SQUARE SQUARE | NOVEMBER| AUGUST 2019 2019 KEY KEY INDICATORS INDICATORS Commercial Real Estate Class A In November, the Times Square Class A commercial offce occu- XXXXXXOCCUPANCY RATE/ XXXXTIMES SQUARE PRICE PER SQUARE FOOT XXXXMIDTOWN pancy rate dropped slightly from PRICE PER SF October to 92%, but remained 95% higher than Midtown's rate of $63 $63 . 93% 90% $66 $63 Between September and Novem- 91% $72 $72 ber, Times Square net effective $74 $78 rent remained unchanged at $63 per square foot. Net effective rent 89% in Midtown saw a sharp increase this month to $78 per square foot.