Movies & Entertainment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assets.Kpmg › Content › Dam › Kpmg › Pdf › 2012 › 05 › Report-2012.Pdf

Digitization of theatr Digital DawnSmar Tablets tphones Online applications The metamorphosis kingSmar Mobile payments or tphones Digital monetizationbegins Smartphones Digital cable FICCI-KPMG es Indian MeNicdia anhed E nconttertainmentent Tablets Social netw Mobile advertisingTablets HighIndus tdefinitionry Report 2012 E-books Tablets Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities 3D exhibition Digital cable Portals Home Video Pay TV Portals Online applications Social networkingDigitization of theatres Vernacular content Mobile advertising Mobile payments Console gaming Viral Digitization of theatres Tablets Mobile gaming marketing Growing sequels Digital cable Social networking Niche content Digital Rights Management Digital cable Regionalisation Advergaming DTH Mobile gamingSmartphones High definition Advergaming Mobile payments 3D exhibition Digital cable Smartphones Tablets Home Video Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Vernacular content Portals Mobile advertising Social networking Mobile advertising Social networking Tablets Digital cable Online applicationsDTH Tablets Growing sequels Micropayment Pay TV Niche content Portals Mobile payments Digital cable Console gaming Digital monetization DigitizationDTH Mobile gaming Smartphones E-books Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Mobile advertising Mobile gaming Pay TV Digitization of theatres Mobile gamingDTHConsole gaming E-books Mobile advertising RegionalisationTablets Online applications Digital cable E-books Regionalisation Home Video Console gaming Pay TVOnline applications -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

And What Are the Lyrics to the Song?

The Twelve Days of Christmas: what are the lyrics to the... https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/occasions/chr... Which are ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’ and what are the lyrics to the song? Sian Moore 2 December 2020, 17:05 | Updated: 3 December 2020, 11:23 It comes up every Christmas, and every year you forget the words (bar ‘Five Gold Rings’, of course). Here’s a handy guide to ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’, including its lyrics and meaning. ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’ is a rootin’-tootin’, singalong Christmas carol that runs through the twelve days that make up the Christmas season – beginning on Christmas Day and ending on 6 January, the day before Epiphany. Each day represents a new gift, starting with ‘a partridge in a pear tree’ and ending with ‘twelve drummers drumming’. It’s a traditional English tune dating back to the 1700s, which some historians actually believe to have French origins. The version we know best came from Frederic Austin, an English composer who set the lyrics and added some flourishes – including the drawn out “five go-old rings” – in 1909. Transform your dollars into lasting change. With fewer Red Kettles to help those who've lost their jobs, your $25 monthly gift is needed now more than ever. salvationarmy.org Sponsored The carol is a cumulative song, which means that each verse is built on top of the previous verses. Read more: The 30 greatest Christmas carols of all time > 1 of 4 12/6/2020, 7:54 PM The Twelve Days of Christmas: what are the lyrics to the.. -

Between the Panels

Between the Panels How the interactions between commerce and art shape superhero comic book film adaptations (2000-13) Tim Stafford Between The Panels: How the interactions between commerce and art shape superhero comic book film adaptations (2000-13) Tim Stafford Submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of PhD January 2018 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my Principal Supervisor, Professor Keith Randle and my Second Supervisors, Visiting Professor Richard Miller and Dr Mariana Dodourova for their support and guidance during this project. I would also like to thank Greg Pan at Marvel for granting permission to reproduce the three selected comic book panels and Roni Lubliner at Universal for granting permission to use the still from Hulk. This thesis is dedicated in its entirety to my parents, Terry and Sheila Stafford, to Derek Watson, my best friend and guide in the world of comic books and to Hugh Jackman, who started the whole thing off. Between the Panels Contents List of figures 1 Abstract 3 Introduction 5 Research questions 8 Introduction to the conceptual framework and methodology 9 Thesis structure 12 Chapter One: Up, up and away: superheroes and their adaptations 14 Origin story: A brief history of superhero adaptations 14 The superhero film renaissance: 2000 to the present 20 Why are superhero films so popular? 26 i) The studio perspective 26 ii) The audience perspective 29 iii) The role of comic book readers 31 The theory of adaptation 34 The role of the director -

Screendollars Newsletter 2020-11-23.Pdf

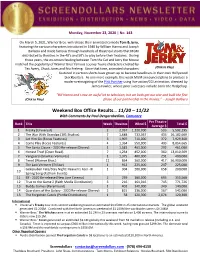

Monday, November 23, 2020 | No. 143 On March 5, 2021, Warner Bros. will release their animated comedy Tom & Jerry, featuring the cartoon characters introduced in 1940 by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera and made famous through hundreds of theatrical shorts that MGM distributed to theatres in the 40’s and 50’s to play before their features. During those years, the on-screen feuding between Tom the Cat and Jerry the Mouse matched the popularity of Warner Bros’ famous Looney Toons characters created by Tex Avery, Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng. Since that time, animated characters (Click to Play) featured in cartoon shorts have grown up to become headliners in their own Hollywood blockbusters. As one more example, this week MGM announced plans to produce a modern reimagining of the Pink Panther using live-action/CGI animation, directed by James Fowler, whose prior successes include Sonic the Hedgehog. “Bill Hanna and I owe an awful lot to television, but we both got our star and built the first (Click to Play) phase of our partnership in the movies.” - Joseph Barbera Weekend Box Office Results… 11/20 – 11/22 With Comments by Paul Dergarabedian, Comscore Per Theatre Rank Title Week Theatres Wknd $ Total $ Average $ 1 Freaky (Universal) 2 2,057 1,220,000 593 5,592,295 2 The War With Grandpa (101 Studios) 7 1,688 733,067 434 16,182,660 3 Let Him Go (Focus Features) 3 1,907 710,000 372 7,929,300 4 Come Play (Focus Features) 4 1,364 550,000 403 8,054,665 5 The Santa Clause - 2020 Re-release (Disney) 1 1,581 461,000 292 461,000 6 Honest Thief (Open -

Hoop Screens: Why Is a Basketball Model Also Best for Predicting The

Hoop Screens: Why is a basketball model also best for predicting the box office? By Ari Levin Advisor Gaston Illanes Northwestern University Mathematical Methods in the Social Sciences Senior Thesis Spring 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3 Literature Review ........................................................................................................................ 4 Data ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Industry Background ................................................................................................................... 8 Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom: Profile of a Blockbuster ..................................................... 9 Limited releases ..................................................................................................................... 18 Miscellaneous ........................................................................................................................ 21 Methods ..................................................................................................................................... 22 Results ...................................................................................................................................... -

This Is a Forced Feminist Agenda:”

Master’s Thesis “This Is a Forced Feminist Agenda:” IMDb users and their understanding of feminism negotiated in the reviews of superheroine films Author: Alžběta Budirská Supervisors: Johan Höglund and Jukka Tyrkkö Examiner: Magnus Levin Date: 31. 5. 2021 Term: VT2021 Subject: Linguistics and Literary Studies Course code: 5EN10E I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the sources listed in references. …………………………………………….. Bc. Alžběta Budirská Abstract The thesis examines how users of the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) negotiate feminism in their reviews of four superheroine films – Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, Birds of Prey: The Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn, and Wonder Woman 1984. By combining critical discourse analysis with methods of corpus linguists, this corpus-based study of over 18,000 reviews analyses the frequency of the topic of feminism in the reviews, words and topics associated with it and the way the reviewers reflect broader mediated discourse over the four films, and the role of IMDb as a space for these reviews. The findings show that feminism is still understood as an anti-male movement where female-led films are shielded from criticism by the mainstream media by the virtue of the lead’s gender, the superheroines are criticised for being overpowered particularly where they have no equal male supporting character and that perceived feminist messaging is usually written off as a forced political agenda or as an insincere cash grab made by corporates which effectively use feminism for promotion. It also reveals IMDb as a highly polarised platform where the users leaving 1- and 10-star reviews are generalized as representatives of different sides of the political spectrum (antifeminist vs feminist, conservative vs liberal) regardless of the actual content of the review. -

La Transformación Digital Y Su Impacto En La Industria Cinematográfica: El Caso De Las Producciones Estereoscópicas

UNIVERSITAT AUTÒNOMA DE BARCELONA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA COMUNICACIÓN LA TRANSFORMACIÓN DIGITAL Y SU IMPACTO EN LA INDUSTRIA CINEMATOGRÁFICA: EL CASO DE LAS PRODUCCIONES ESTEREOSCÓPICAS. TESIS DOCTORAL AÑO 2013 TESIS ELABORADA POR EMILIO MOLINA ORDÓÑEZ DIRECTORA DE LA TESIS Dra. ROSA FRANQUET i CALVET (Departamento de Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad) SUMARIO Resumen/Summary ..............................................................................................................5! Introducción .........................................................................................................................7! Justificación e interés del tema ............................................................................................8! Planteamiento del problema...............................................................................................15! Hipótesis de la investigación .............................................................................................15! Estructura de la investigación ............................................................................................16! Metodología de la tesis: Estrategia cuantitativa y cualitativa............................................18! ! PARTE PRIMERA! LA TRANSFORMACIÓN DIGITAL............................................................................21! CAPÍTULO PRÍMERO! El modelo digital................................................................................................................23! 1.1. El dominio digital .......................................................................................................24! -

Screendollars July 27, 2020 About Films, the Film Industry No

For Exhibitors Screendollars July 27, 2020 About Films, the Film Industry No. 127 Newsletter and Cinema Advertising Happy 92nd birthday to filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, born in Manhattan on July 26, 1928. He died of a heart attack at the age of 70, during post-production work on Eyes Wide Shut, his 13th feature film. His approach to filmmaking was meticulous, bordering on obsessive. He exercised full control of his projects and spent years making each film. Audiences often left a Kubrick film screening asking themselves “What does it mean?” but also fascinated with the intensity of its characters and details of the world he had created. In the 1970’s, a whispered conspiracy theory arose that NASA had enlisted Kubrick to stage and film a fake moon landing once they realized the impossibility of accomplishing the task. In a sense, it was an homage to the detail Kubrick brought to his creations. His best known films include Spartacus (1960) starring Kirk Douglas and Laurence Olivier, Lolita (1962) starring James Mason, Dr. Strangelove (1964) starring Peter Sellers, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), The Shining (1980) (Click to Play) starring Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall and Full Metal Jacket (1987). (Click to Play) “Never try to explain something that you don’t understand yourself.” - Stanley Kubrick Notable Industry News and Commentary (7/20-26) #SaveYourCinema Campaign While lawmakers in Washington are debating the next economic stimulus and relief package, it is vital that exhibitors be heard. NATO has developed a terrific campaign to assist theatre owners in contacting their US Senators and Representatives to explain their plight and ask for support. -

The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies

$€ social sciences £ ¥ The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies Edited by Lauren Dundes Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Social Sciences www.mdpi.com/journal/socsci The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies Special Issue Editor Lauren Dundes MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Lauren Dundes Department of Sociology, McDaniel College USA Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Social Sciences (ISSN 2076-0760) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ socsci/special issues/Disney Movies Psychosocial Implications) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-848-0 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-849-7 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Hsun-yuan Hsu. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”The Psychosocial Implications of Disney Movies” .................. -

Focus Marché Du Film 2018

EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY CONFERENCE 2018 FOCUS TENDANCES DU MARCHÉ MONDIAL DU FILM WORLD FILM MARKET TRENDS Observatoire européen de l’audiovisuel European Audiovisual Observatory Europäische Audiovisuelle Informationsstelle SETTING THE STAGE FOR INNOVATIVE MEDIA PRODUCTION A vibrant business community of the most talented minds in film production, TV and broadcasting industries dedicated to excellence in media production. Dubai Studio City features a star cast of regional and international companies, along with world-class sound stages, studios and advanced services. A member of TECOM Group www.dubaistudiocity.ae focus 2018 World Film Market Trends Tendances du marché mondial du film Pages Pub int Focus 2010:Pub Focus 29/04/10 10:54 Page 1 ISSN: 1962-4530 Lay-out: Acom*Europe | © 2011, Marché du Film | Printed: Global Rouge, Les Deux-Ponts Imprimé sur papier labélisé issu de forêts gérées durablement. Imprimé sur papier labelisé issu de forêts gérées durablement. Printed on paper from sustainably managed forests. Printed on paper from sustainably managed forests. 2 Editors Martin Kanzler ([email protected]) Patrizia Simone ([email protected]) Julio Talavera Milla ([email protected]) Film Analysts, Department for Market Information, European Audiovisual Observatory LUMIERE Database Laura Ene Lay-out: Acom* Media (Paris) © 2018, Marché du Film Printed: Global Rouge (Les Deux-Ponts) 2 Editorial Already the 20th edition of FOCUS! I am very Déjà la 20ème édition de FOCUS ! Je suis très happy with our long-term relationship with heureux de notre relation de longue date avec the European Audiovisual Observatory. FOCUS l’Observatoire Européen de l’Audiovisuel. FOCUS, remains an essential reference guide for profes- est une référence incontournable pour tous les participants professionnels.