Health Policy Responses and Infrastructure Re-Use in Host Cities of Mega-Sporting Events in Non-Traditional Host Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Employment Equity Act: Public Register

STAATSKOERANT, 7 MAART 2014 No. 37426 3 CORRECTION NOTICE Extraordinary National Gazette No. 37405, Notice No. 146 of 7 March 2014 is hereby withdrawn and replaced with the following: Gazette No. 37426, Notice No. 168 of 7 March 2014. GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 168 OF 2014 PUBLIC REGISTER NOTICE EMPLOYMENT EQUITY ACT, 1998 (ACT NO. 55 OF 1998) I, Mildred Nelisiwe Oliphant, Minister of Labour, publish in the attached Schedule hereto the register maintained in terms of Section 41 of the Employment Equity Act, 1998 (Act No. 55 of 1998) of designated employers that have submitted employment equity reports in terms of Section 21, of the Employment Equity Act, Act No. 55 of 1998. 7X-4,i_L4- MN OLIPHANT MINISTER OF LABOUR vc/cgo7c/ t NOTICE 168 OF 2014 ISAZISO SASEREJISTRI SOLUNTU UMTHETHO WOKULUNGELELANISA INGQESHO, (UMTHETHO YINOMBOLO YAMA-55 KA-1998) Mna, Mildred Nelisiwe Oliphant, uMphathiswa wezabasebenzi, ndipapasha kule Shedyuli iqhakamshelwe apha irejista egcina ngokwemiqathango yeCandelo 41 lomThetho wokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho, ka-1998 (umThetho oyiNombolo yama- 55 ka-1998)izikhundlazabaqeshi abangeniseiingxelozokuLungelelanisa iNgqeshongokwemigaqo yeCandelo 21, lomThethowokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho, umThetho oyiNombolo yama-55 ka-1998. MN OLIPHANT UMPHATHISWA WEZEMISEBENZI oVe7,742c/g- This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 4 No. 37426 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 7 MARCH 2014 List of designated employers who reported for the 01 September 2013 reporting cycle No: This represents sequential numbering of designated employers and bears no relation to an employer. (The list consists of 4984 large employers and 10182 small employers). Business name: This is the name of the designated employer who reported. Status code: 0 means no query. -

SY3057 Football and Society | Readinglists@Leicester

09/30/21 SY3057 Football and Society | readinglists@leicester SY3057 Football and Society View Online 1. Lewis, R. W. Innovation not Invention: A Reply to Peter Swain Regarding the Professionalization of Association Football in England and its Diffusion. Sport in History 30, 475–488 (2010). 2. Allison, Lincoln. Association Football and the Urban Ethos. Stanford Journal of International Studies (1978). 3. Bailey, S. Living Sports History: Football at Winchester, Eton and Harrow. The Sports Historian 15, 34–53 (1995). 4. Baker, N. Whose Hegemony? The Origins of the Amateur Ethos in Nineteenth Century English Society. Sport in History 24, 1–16 (2004). 5. Dunning, E. Sport matters: sociological studies of sport, violence, and civilization. (Routledge, 2001). 6. Dunning, E. & Sheard, K. G. Barbarians, gentlemen and players: a sociological study of the 1/42 09/30/21 SY3057 Football and Society | readinglists@leicester development of rugby football. (Frank Cass, 2005). 7. Garnham, N. Patronage, Politics and the Modernization of Leisure in Northern England: the case of Alnwick’s Shrove Tuesday football match. The English Historical Review 117, 1228–1246 (2002). 8. Giulianotti, R. Football: a sociology of the global game. (Polity Press, 1999). 9. Harvey, A. Football: the first hundred years : the untold story. vol. Sport in the global society (Routledge, 2005). 10. Holt, R. Sport and the British: a modern history. vol. Oxford studies in social history (Clarendon Press, 1989). 11. Hutchinson, J. Sport, Education and Philanthropy in Nineteenth-century Edinburgh: The Emergence of Modern Forms of Football. Sport in History 28, 547–565 (2008). 12. Kitching, G. ‘From Time Immemorial’: The Alnwick Shrovetide Football Match and the Continuous Remaking of Tradition 1828–1890. -

GREEN-PASSPORT-L8.Pdf

1 www. ), which have been raising been raising ), which have t Dear Passport Green Holder, and largest the world’s and to South to Africa Welcome World most spectacular sporting the 2010 FIFA event, soil. African for the first time on hosted Cup™, Olympic hosts and Games, the 1994 Winter Since of major sportingorganisers been challenged have events impact on the environment. their negative reduce to National DepartmentThe South African of Environmental (DEA), in partnershipAffairs Nations with the United and the Global (UNEP) Programme Environment implemented have (GEF), Facility Environment reduction such as areas carbon projects addressing and water energy management, transportation, waste efficiencytrees well as the planting under the of as the carbon reduce to Programme National Greening Cup™. World footprint of the 2010 FIFA is an Cup™ World PassportThe Green for the 2010 FIFA and is being rolled UNEP/GEF, by initiative international as partout in South Africa of the legacy of the component initiative. national greening DEA’s 2008, UNEP has been the global and promoting Since other national Green Passport ( campaigns several unep.org/greenpasspor about among to their potential tourists awareness making responsible by sustainable tourism to contribute holiday choices. WELCOME TO THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA NAME SURNAME MOBILE UNIQUE PASSPORT NO. 000 001 EMAIL COUNTRY OF ORIGIN Register your unique passport number on the Green Passport website www.greenpassport.co.za, and you will be automatically entered into a draw to WIN a fantastic two night stay at one of South Africa’s private luxury game reserves, The Thornybush Collection. See page 5 for details and sign up to the Green Nation! WHAT IS EVENT GREENING AND G REENIN During our participation in the 2010 FIFA World Cup™, let us all WHAT IS SOUTH AFRICA DOING strive to behave in an environmentally responsible manner so that TO ADDRESS THIS FOR THE succeeding generations can also have the opportunity to enjoy 2010 FIFA WORLD CUP™? G international sporting events in a safe and natural environment. -

2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee South Africa FIFA Confederations Cup Success

2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee South Africa FIFA Confederations Cup success 8 teams 16 matches 4 cities 4 stadiums 584 894 spectators (vast majority South Africans) 4 030 volunteers worked during the tournament FCC Broad Overview What went well? Areas for improvement • South African people underpinning • Process and communication around warm tournament atmosphere sale of tickets and skyboxes • Very positive feedback for services • Quality and quantity of food provided provided to PMA’s and referees for hospitality areas, spectators and sponsors,media volunteers • Commitment and dedication of staff at • Safety and security planning and both venues and HQ implementation • Friendly, helpful and well trained • Protocol, especially for VIP and volunteers VVIP’s • Good local and international press • Pitch quality in light of rugby transition coverage • Park and Ride service in cooperation • Great support from the South African with Host Cities public • Memorable fan experience FIFA Confederations Cup success WORLD-CLASS TEAMS AND WORLD-CLASS FOOTBALL •Spectators – 584894 •510,008 tickets sold •An average of 36556 spectators per game •Higher than the spectator average in previous FIFA Confederations Cups - Korea/Japan (01) and France (03), Germany (37 694) FIFA Confederations Cup success FIFA Confederations Cup success SOUTH AFRICA UNITED “We always said that the hosting of these tournaments must be about nation building - the images we have seen in the last week that have gone around the world are pictures of our rainbow nation like we have never seen before. They are not staged, they are real. We have come together as a nation and showed the world that we truly are a soccer-loving nation” Dr Danny Jordaan, FIFA Confederations Cup success STADIUMS •The stadiums were all ready on time and given the FIFA stamp of approval. -

2014 Russian Media

TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 GENERAL INFORMATION Sochi Autodrom Specifics 3–5 Media Services Map 6 Timetable 7-8 PART 2 MEDIA SERVICES Responsible: Track / FIA / Media Centre 9 Accreditation Centre / Media Centre Opening Hours 10 Press / Photographers' Area 11 Shuttle Buses: Routes / Timetable 12 Press Conferences 13 PART 3 2017 FIA FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 2017 Regulation Changes 14 Calendar 15 Entry List 16 Circuit Characteristics & Results — AUSTRALIAN GRAND PRIX 17–18 Circuit Characteristics & Results — CHINESE GRAND PRIX 19–20 Circuit Characteristics & Results — BAHRAIN GRAND PRIX 21–22 Circuit Characteristics — RUSSIAN GRAND PRIX 23 Circuit Characteristics — SPANISH GRAND PRIX 24 Circuit Characteristics — MONACO GRAND PRIX 25 Circuit Characteristics — CANADIAN GRAND PRIX 26 Circuit Characteristics — AZERBAIJAN GRAND PRIX 27 Circuit Characteristics — AUSTRIAN GRAND PRIX 28 Circuit Characteristics — BRITISH GRAND PRIX 29 Circuit Characteristics — HUNGARIAN GRAND PRIX 30 Circuit Characteristics — BELGIAN GRAND PRIX 31 Circuit Characteristics — ITALIAN GRAND PRIX 32 Circuit Characteristics — SINGAPORE GRAND PRIX 33 Circuit Characteristics — MALAYSIAN GRAND PRIX 34 Circuit Characteristics — JAPANESE GRAND PRIX 35 Circuit Characteristics — UNITED STATES GRAND PRIX 36 Circuit Characteristics — MEXICAN GRAND PRIX 37 Circuit Characteristics — BRAZILIAN GRAND PRIX 38 Circuit Characteristics — ABU DHABI GRAND PRIX 39 Sochi Autodrom 354340, Russian Federation Krasnodar region Sochi, Adler, Triumfalnaya str. 26 +7 (862) 241-90-50, +7 (862) -

CRUNCH TIME Behind Closed Door at the FIA Crash Tests That Keep Formula One Safe

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA: ISSUE #2 ROAD TO RUIN REVIVING THE EURO Travelling one of the world’s Formerly unloved and most dangerous highways in uncompetitive, the European Bangladesh and how the FIA Rally Championship has is helping reduce the risk P34 had a major makeover P62 THE BEAR ROARS AUTO PILOT PROJECTS From taking road safety to Once the stuff of science fiction, the global stage to building autonomous cars are close to new arenas for world motor becoming the comfortable and sport, Russia is rising P50 safe future of motoring P68 P42 CRUNCH TIME Behind closed door at the FIA crash tests that keep Formula One safe ISSUE #2 BEHIND THE SCENES THE FIA The Fédération Internationale In motor sport, the racing is de l’Automobile is the governing body of world motor sport and the just the tip of the iceberg, the federation of the world’s leading INTERNATIONAL motoring organisations. Founded culmination of months of JOURNAL OF THE FIA in 1904, it brings together 232 national motoring and sporting organisations from 134 countries, technical work to ensure both Editorial Board: representing millions of motorists JEAN TODT, NORMAN HOWELL, worldwide. In motor sport, car and driver have reached GERARD SAILLANT, RICHARD WOODS, it administers the rules and TIM KEOWN, DAVID WARD regulations for all international the highest standards. Editors-in-chief: four-wheel sport, including the FIA NORMAN HOWELL, RICHARD WOODS Formula One World Championship Executive Editor: MARC CUTLER and FIA World Rally Championship This is never more the case than where safety is Editor: JUSTIN HYNES concerned. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. ‘These whites never come to our game. What do they know about our soccer?’ Soccer Fandom, Race, and the Rainbow Nation in South Africa Marc Fletcher PhD African Studies The University of Edinburgh 2012 ii The thesis has been composed by myself from the results of my own work, except where otherwise acknowledged. It has not been submitted in any previous application for a degree. Signed: (MARC WILLIAM FLETCHER) Date: iii iv ABSTRACT South African political elites framed the country’s successful bid to host the 2010 FIFA World Cup in terms of nation-building, evoking imagery of South African unity. Yet, a pre-season tournament in 2008 featuring the two glamour soccer clubs of South Africa, Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates, and the global brand of Manchester United, revealed a racially fractured soccer fandom that contradicted these notions of national unity through soccer. -

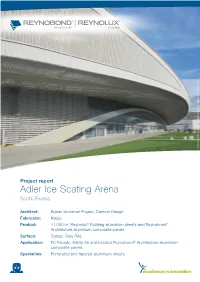

Adler Ice Scating Arena | Kuban Universal Project, Cannon Design | Kuban Universal Project, Adler Ice Scating Arena

Adler Ice Scating Arena | Kuban Universal Project, Cannon Design | Kuban Universal Project, Adler Ice Scating Arena Project report Adler Ice Scating Arena Sochi, Russia Architect: Kuban Universal Project, Cannon Design Fabricator: Kalzip Product: 11,000 m2 Reynolux® Building aluminium sheets and Reynobond® Architecture aluminium composite panels Surface: Colour: Grey RAL Application: FC Facade, Kalzip 65 and bended Reynobond® Architecture aluminium composite panels Specialties: Perforated and tapered aluminium sheets Adler Ice Scating Arena Ice crystal-inspired surface made of Reynolux® Building Six spectacular new sporting stadiums – together covering some 150,000 m2 – are a memorable and enduring feature of the 2014 Winter Olympic Games at Sochi, Russia. Oleg Kharchenko, chief architect at SC Olympstroy, the state corpo- ration for construction of Sochi’s Olympic venues, described the Sochi Olympic Park as ‘an architectural ensemble incor- porating a diverse array of façades, colours and textures’. Tata Steel subsidiary and manufacturer of tailored metal building envelopes Kalzip has made a significant contribution to this image, as it was involved in the complex designs of two of the six stadiums: namely the Bolshoy Ice Dome, home to the Games' main ice hockey matches; and the similarly curvilinear yet distinctly ice crystal inspired Adler Skating Arena. The Adler Arena Skating Center (now the Adler Arena Trade and Exhibition Center) opened in 2012 as an 8,000-seat speed-skating oval. In plan though, this cool grey and white building is essentially a rectangle with rounded corners. Angled walls and triangular sections of glazing reinforce the building’s intentionally crystalline surface appearance. The $ 32.8 million building was designed by the Russian company Kuban Univer- sal Project and the international architectural and engineering firm Cannon Design, responsible for the Richmond Oval for the 2010 Vancouver Winter Games, designed its clean-lined interior, which housed two competition lanes as well as a training area. -

ISLJ 2002/3Def 29-06-2004 15:48 Pagina A

ISLJ 2002/3Def 29-06-2004 15:48 Pagina A 2002/3 Affirmative Action in South-African Sport International Sports Law in United States The Ellis Park Disaster Transfers and Agents European Social Dialogue in Football Sport and Development Cooperation ISLJ 2002/3Def 29-06-2004 15:48 Pagina B Congres ‘Sport & Fiscus’ Actuele fiscaliteiten op sportgebied Donderdag 24 april 2003 (De locatie is nog niet bekend) De belangrijkste thema’s die aan de orde komen: • Loonbelasting • • Internationaal • Rien Vink, Senior Belastingadviseur bij Ernst & Young Drs. Wiebe Brink, Partner bij Ernst & Young Belastingadviseurs in Utrecht Belastingadviseurs in Utrecht en universitair docent belast- O.a.: Wie is (fiscaal) (beroeps)sporter? Kan de sponsor ingrecht aan de Erasmus Universiteit te Rotterdam. de sporter geld geven zonder consequenties voor het O.a.: Toedeling van heffingsbevoegdheden aan NL of het stipendium? Zijn de kosten van o.a. voedingssupple- buitenland bij sportevenementen. Subject en object van menten en mentale training van de sporter onbelast te heffing voor verdragsdoeleinden. Toepassing vri- vergoeden? Zijn transfersommen (on)belast? jstellings- en verrekenings-methode. Fiscale behandeling Imagerechten. uitkeringen nabetaald salaris en pensioen. Vergelijking van het Nederlandse met andere Europese fiscale stelsels voor sporters en sportverdiensten. • BTW • Voor wie is dit congres interessant? Drs. Gerard Brand, Belastingdienst Grote Ondernemingen, Accountants, belastingadviseurs en fiscalisten die Utrecht (top)sporters en sportverenigingen adviseren, financieel O.a.: De (beroeps)sporter, de sportorganisatie en de directeuren van sportverenigingen, medewerkers van de BTW. Sportsponsoring in geld en natura. Belastingdienst, medewerkers van het Ministerie VWS, Zaakwaarnemers /spelers-begeleiding in het betaald sportbonden, sportmakelaars, voetbal. Verhuur van skyboxes, business units en busi- sportadvocaten, sportjournalisten, zaakwaarnemers. -

A Sochi Winter Olympics

Official Newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia Edition 25 - June 2014 Asia at Sochi 2014 OCA HQ hosts IOC President OCA Games Update OCA Media Committee Contents Inside your 32-page Sporting Asia 3 OCA President’s Message OCA mourns Korean ferry tragedy victims Sporting Asia is the official 4 – 8 NEWS DIGEST newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia, published 4 Hanoi withdraws as Asian Games host in 2019 quarterly. Kuala Lumpur counts down to IOC Session in 2015 OCA Education Committee Chairman passes away 11 Executive Editor / Director General OCA assists with 2nd COC Youth Camp Husain Al Musallam [email protected] 5 China’s Yu Zaiqing returns as IOC Vice President Children of Asia Games recognise OCA input Art Director / IT Director Top IOC posts for Asian sports leaders Amer Elalami [email protected] 6 ANOC Ex-Co and Olympic Solidarity Commission in Kuwait Director, Int’l & NOC Relations Vinod Tiwari 7 IOC President visits Kuwait, Qatar [email protected] and Saudi Arabia Anti-Doping activities Director, Asian Games Department 22 8 Haider A. Farman [email protected] OS/OCA Regional Forums in Bahrain, Myanmar 9 10 Inside the OCA Editor Jeremy Walker OCA Media Committee [email protected] OCA IT Audit in Thailand Executive Secretary 11 – 22 WELCOME TO SOCHI! Nayaf Sraj [email protected] Twelve pages of Asia at the Winter Olympics starts here Olympic Council of Asia PO Box 6706, Hawalli 23 Overview, Facts and Figures, Photo Gallery 12 – 13 Zip Code 32042 Kuwait 14 Four Asian NOCs join medal rush Telephone: +965 22274277 - 88 15 Final medals -

Copyrighted Material

34_035374 bindex.qxp 7/28/06 9:25 PM Page 341 Index 1991 World Cup game, 183 • A • Olympic rugby, 196 Abbott, Stuart (rugby player), 211 2003 World Cup game, 185–186, 283–284 abdomen stretch, 143–144 award of scrum feed, 73 accuracy, 92 Ackford, Paul (rugby player), 120 • B • advantage, 68, 73, 321 advantage line, 129 Back, Neil (rugby player), 58 Age Grade rugby, 225, 321 back (player), 45, 53–60, 321. See also agility, 147 specific types alcohol, 152, 153 back row Alickadoos (volunteers), 321 definition, 321 All Blacks vs Springboks (video), 247 overview, 51–53 Amatori & Calvisano (team), 339 scrum formation, 110 Amin, Idi (rugby player), 294 strategy coordination, 129–130 Andrew, Rob (rugby player), 179 back three, 321 Anglo-Welsh Cup (competition), 221 backs coach, 168 ankle tap, 100, 321 Bahrain, 295 Apartheid policy, 197 ball Art of Coarse Rugby (Green), 258 carrier, 322 AS Beziers Herault (team), 338 kicking skills, 84–94 assistant coach, 168 lineouts, 116–122 association football, 10 maul creation, 105–106 attack plan, 136–139 overview, 34–35 attitude, 149–151 passing skills, 91–96 Australian dispensation, 281 ruck formation, 102–103 Australian Rugby ReviewCOPYRIGHTED(magazine), 260 running MATERIAL skills, 79–80 Australian Rugby Union, 336 tackle laws, 69–70 Australian team Ballymore (stadium), 205 England match, 312–313 Barbarians (team), 290, 299 1987 World Cup game, 182–183 Barbed Wire Boks (Cameron), 258 34_035374 bindex.qxp 7/28/06 9:25 PM Page 342 342 Rugby Union For Dummies, 2nd Edition Barnes, Stuart (commentator), 239 brothers, 301 Bath team, 210, 217, 336 Brown brothers, 301 Battle of Ballymore (famous match), 112 Brown, Ross (rugby player), 199 Bayfield, Martin (rugby player), 112 Burger, Schalk (rugby player), 189 BBC (broadcast channel), 238, 240–241, Burnett, Bob (rugby player), 112 256 Burton, Mike (rugby player), 112 Beaumont, Bill (coach), 201 Bush, George Jr. -

Fifa 2010 World Cup

FIFA 2010 WORLD CUP Transport Technical Report Part B July 2003 Prepared by: CSIR HHO Africa Arup Contact person: Mr Richard Gordge CSIR Transportek P O Box 395 Stellenbosch South Africa 7599 Tel: +27 21 888-2611 Fax: +27 21 888-2694 Email: [email protected] Date: July 2003 PART B FIFA 2010 World Cup Contents 1. GAUTENG_________________________________________ 1 1.1 General Transport Review ___________________________________________ 1 1.2 Transport Mode Split ________________________________________________ 1 1.3 Airports_____________________________________________________________ 2 1.4 Road Network _______________________________________________________ 2 1.4.1 National Links ________________________________________________________ 2 1.4.2 Gauteng Network ______________________________________________________ 3 1.4.3 Patterns of Demand for Road Space______________________________________ 3 1.4.4 Congestion Management Strategy ________________________________________ 3 1.4.5 Road Infrastructure Upgrade Programs___________________________________ 4 1.4.6 Major Road Routes for the FIFA 2010 World Cup _______________________ 4 1.5 Public Transport ____________________________________________________ 5 1.5.1 Overview ______________________________________________________________ 5 1.5.2 Gautrain Rapid Rail___________________________________________________ 7 1.5.3 Rail Extensions and Stations ____________________________________________ 8 1.6 Key Issues relating to the Effective Hosting of the FIFA 2010 World Cup ________________________________________________________________