U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methane Emissions from Forests Ecosystems Enhance Global Warming? : Keppler Et.Al.(2006)

Methane emissions from forests ecosystems enhance global warming? : Keppler et.al.(2006). Methane emissions from terrestrial plants under aerobic conditions. Nature 439: 187-191 Quantifications of possible effects and comments Summary The results of this study could affect attractiveness and returns of CDM carbon offset projects and future negotiations about carbon sinks in the second commitment period. If confirmed independently, they represent a paradigm shift regarding methane formation in plant physiology. When extrapolated, net greenhouse gas removals by growing forests, e.g. existing forests or forests created by afforestation projects under the Clean Development Mechanism, could be reduced by maximally 4-8% though aerobic emissions of methane by trees. Net actual effects are likely to be lower. However, transposing and up-scaling results obtained in containers on small samples, seedlings, and on only one tree species to global forests and other biomes is not a valid “first estimate”, but at best a hypothesis which should be tested. Results do not invalidate the role of forests as carbon sinks; they also do not support the view that deforestation mitigates global warming via reduced emissions of methane. Background The paper postulates a sizeable, previously unknown methane source of 60-240 Mt from forests and other biomes, and an additional source of 1-7 Mt CH4 from litter. Plant physiology has up to now not recognized the possibility of aerobic methane formation by intact plants or litter. Methane, a powerful greenhouse gas with a global warming potential of 23 times that of CO2, has been thought to originate in rice patties, natural wetlands, landfills, natural gas reservoirs, biomass burning and in the digestive tracts of cattle.If these methane emissions can be corroborated, the discovery amounts to a paradigm shift in plant physiology. -

Synthetic Greenhouse Gases

Synthetic Greenhouse Gases How are they different to What are ‘synthetic greenhouse gases’? ‘greenhouse gases’? Synthetic greenhouse gases are man made Greenhouse gases are naturally occurring. chemicals. They are commonly used in They include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane refrigeration and air conditioning, fire (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Synthetic extinguishing, foam production and in greenhouse gases are man made chemicals medical aerosols. When they are released, and generally have a much higher global synthetic greenhouse gases trap heat in warming potential than naturally occurring the atmosphere. greenhouse gases. What is global warming potential? Global warming potential (GWP) is a measure of how much heat a greenhouse gas traps in the atmosphere over a specific time compared to a similar mass of carbon dioxide (CO2). CO2, with a global warming potential of 1, is used as the base figure for measuring global warming potential. The higher the global warming potential number, the more heat a gas traps. The most common synthetic greenhouse gas in Australia is HFC-134a, which is mostly used in refrigerators and air conditioners. It has a global warming potential of 1430; this means the release of one tonne of HFC-134a is equivalent to releasing 1430 tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. Which synthetic greenhouse gases does 22,800 Australia regulate? SF6 the global warming potential of sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) • hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) • perfluorocarbons (PFCs) • sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) Synthetic • nitrogen trifluoride (NF3) greenhouse gases account for around 2% of all greenhouse gas emissions in Australia How do we use synthetic greenhouse gases? They are man made chemicals with a wide variety of uses. -

Accounting for the Climate–Carbon Feedback in Emission Metrics

Earth Syst. Dynam., 8, 235–253, 2017 www.earth-syst-dynam.net/8/235/2017/ doi:10.5194/esd-8-235-2017 © Author(s) 2017. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Accounting for the climate–carbon feedback in emission metrics Thomas Gasser1,2,a, Glen P. Peters2, Jan S. Fuglestvedt2, William J. Collins3, Drew T. Shindell4, and Philippe Ciais1 1Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, LSCE/IPSL, Université Paris-Saclay, CEA – CNRS – UVSQ, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 2Center for International Climate and Environmental Research – Oslo (CICERO), 0349 Oslo, Norway 3Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, Reading, RG6 6BB, UK 4Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA anow at: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), 2361 Laxenburg, Austria Correspondence to: Thomas Gasser ([email protected]) Received: 4 November 2016 – Discussion started: 10 November 2016 Accepted: 20 March 2017 – Published: 10 April 2017 Abstract. Most emission metrics have previously been inconsistently estimated by including the climate– carbon feedback for the reference gas (i.e. CO2) but not the other species (e.g. CH4). In the fifth assessment report of the IPCC, a first attempt was made to consistently account for the climate–carbon feedback in emission metrics. This attempt was based on only one study, and therefore the IPCC concluded that more research was needed. Here, we carry out this research. First, using the simple Earth system model OSCAR v2.2, we establish a new impulse response function for the climate–carbon feedback. Second, we use this impulse response func- tion to provide new estimates for the two most common metrics: global warming potential (GWP) and global temperature-change potential (GTP). -

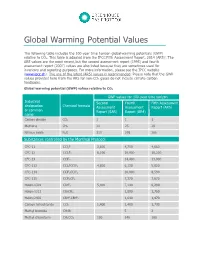

Global Warming Potential Values

Global Warming Potential Values The following table includes the 100-year time horizon global warming potentials (GWP) i relative to CO2. This table is adapted from the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, 2014 (AR5) . The AR5 values are the most recent, but the second assessment report (1995) and fourth assessment report (2007) values are also listed because they are sometimes used for inventory and reporting purposes. For more information, please see the IPCC website (www.ipcc.ch). The use of the latest (AR5) values is recommended. Please note that the GWP values provided here from the AR5 for non-CO2 gases do not include climate-carbon feedbacks. Global warming potential (GWP) values relative to CO2 GWP values for 100-year time horizon Industrial Second Fourth Fifth Assessment designation Chemical formula Assessment Assessment Report (AR5) or common Report (SAR) Report (AR4) name Carbon dioxide CO2 1 1 1 Methane CH4 21 25 28 Nitrous oxide N2O 310 298 265 Substances controlled by the Montreal Protocol CFC-11 CCl3F 3,800 4,750 4,660 CFC-12 CCl2F2 8,100 10,900 10,200 CFC-13 CClF3 14,400 13,900 CFC-113 CCl2FCClF2 4,800 6,130 5,820 CFC-114 CClF2CClF2 10,000 8,590 CFC-115 CClF2CF3 7,370 7,670 Halon-1301 CBrF3 5,400 7,140 6,290 Halon-1211 CBrClF2 1,890 1,750 Halon-2402 CBrF2CBrF2 1,640 1,470 Carbon tetrachloride CCl4 1,400 1,400 1,730 Methyl bromide CH3Br 5 2 Methyl chloroform CH3CCl3 100 146 160 GWP values for 100-year time horizon Industrial Second Fourth Fifth designation Chemical formula assessment Assessment Assessment or common report (SAR) -

Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2015

ANNEX 6 Additional Information 6.1. Global Warming Potential Values Global Warming Potential (GWP) is intended as a quantified measure of the globally averaged relative radiative forcing impacts of a particular greenhouse gas. It is defined as the cumulative radiative forcing–both direct and indirect effectsintegrated over a specific period of time from the emission of a unit mass of gas relative to some reference gas (IPCC 2007). Carbon dioxide (CO2) was chosen as this reference gas. Direct effects occur when the gas itself is a greenhouse gas. Indirect radiative forcing occurs when chemical transformations involving the original gas produce a gas or gases that are greenhouse gases, or when a gas influences other radiatively important processes such as the atmospheric lifetimes of other gases. The relationship between kilotons (kt) of a gas and million metric tons of CO2 equivalents (MMT CO2 Eq.) can be expressed as follows: MMT MMT CO2 Eq. kt of gas GWP 1,000 kt where, MMT CO2 Eq. = Million metric tons of CO2 equivalent kt = kilotons (equivalent to a thousand metric tons) GWP = Global warming potential MMT = Million metric tons GWP values allow policy makers to compare the impacts of emissions and reductions of different gases. According to the IPCC, GWP values typically have an uncertainty of 35 percent, though some GWP values have larger uncertainty than others, especially those in which lifetimes have not yet been ascertained. In the following decision, the parties to the UNFCCC have agreed to use consistent GWP values from the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4), based upon a 100 year time horizon, although other time horizon values are available (see Table A-263). -

Greenhouse Gas and Global Warming Potential Excerpt from U.S. National Emissions Inventory

GREENHOUSE GASES AND GLOBAL WARMING POTENTIAL VALUES EXCERPT FROM THE INVENTORY OF U.S. GREENHOUSE EMISSIONS AND SINKS: 1990-2000 U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Program Office of Atmospheric Programs U.S. Environmental Protection Agency April 2002 Greenhouse Gases and Global Warming Potential Values Original Reference All material taken from the Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990 - 2000, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Atmospheric Programs, EPA 430-R-02- 003, April 2002. <www.epa.gov/globalwarming/publications/emissions> How to Obtain Copies You may electronically download this document from the U.S. EPA’s Global Warming web page on at: www.epa.gov/globalwarming/publications/emissions For Further Information Contact Mr. Michael Gillenwater, Office of Air and Radiation, Office of Atmospheric Programs, Tel: (202)564-0492, or e-mail [email protected] Acknowledgments The preparation of this document was directed by Michael Gillenwater. The staff of the Climate and Atmospheric Policy Practice at ICF Consulting, especially Marian Martin Van Pelt and Katrin Peterson deserve recognition for their expertise and efforts in supporting the preparation of this document. Excerpt from Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2000 Page 2 Greenhouse Gases and Global Warming Potential Values Introduction The Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions elements of the Earth’s climate system. Natural and Sinks presents estimates by the United States processes such as solar-irradiance variations, government of U.S. anthropogenic greenhouse variations in the Earth’s orbital parameters, and gas emissions and removals for the years 1990 volcanic activity can produce variations in through 2000. -

Global Warming Potential (GWP) of Refrigerants: Why Are Particular Values Used?

OZONACTION FACT SHEET Global Warming Potential (GWP) of Refrigerants: Why are Particular Values Used? INTRODUCTION Ever since the Montreal Protocol agreed to phase out hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), there has been an increasing interest within the Protocol on climate issues. The now famous Decision XIX/6, taken in 2007, to adjust the Protocol to accelerate the phase out of HCFCs includes language to encourage the promotion of alternatives that minimise environmental impacts, in particular impacts on climate, as well as to prioritise funding for projects, inter alia, which focus on substitutes and alternatives that minimise other impacts on the environment, ©Shutterstock including on the climate, taking into account global- warming potential (GWP). In your work you may come across various GWP Current discussions on the Montreal Protocol figures from technical experts, industry and other potentially being amended to facilitate the phase- stakeholders which may not appear to be down of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) bring the issue consistent. This could be due to the fact that the of climate change and associated monitoring and values quoted are from different sources or reporting to the forefront of the Protocol. different sets of GWP values. WHAT IS GWP? Global warming potential (GWP) is a measure of the The higher the GWP value, the more that particular relative global warming effects of different gases. It gas warms the Earth compared to carbon dioxide. assigns a value to the amount of heat trapped by a certain mass of a gas relative to the amount of heat GWP values for ozone depleting substances can trapped by a similar mass of carbon dioxide over a range, for example, from 2 up to about 14,000. -

September, 2009 October, 2009 December 7, 2009

ney September,October, 2009 2009 December 7, 2009 i Acknowledgments EPA authors and contributors: Benjamin DeAngelo, Jason Samenow, Jeremy Martinich, Doug Grano, Dina Kruger, Marcus Sarofim, Lesley Jantarasami, William Perkins, Michael Kolian, Melissa Weitz, Leif Hockstad, William Irving, Lisa Hanle, Darrell Winner, David Chalmers, Brian Cook, Chris Weaver, Susan Julius, Brooke Hemming, Sarah Garman, Rona Birnbaum, Paul Argyropoulos, Al McGartland, Alan Carlin, John Davidson, Tim Benner, Carol Holmes, John Hannon, Jim Ketcham-Colwill, Andy Miller, and Pamela Williams. Federal expert reviewers Virginia Burkett, USGS; Phil DeCola; NASA (on detail to OSTP); William Emanuel, NASA; Anne Grambsch, EPA; Jerry Hatfield, USDA; Anthony Janetos; DOE Pacific Northwest National Laboratory; Linda Joyce, USDA Forest Service; Thomas Karl, NOAA; Michael McGeehin, CDC; Gavin Schmidt, NASA; Susan Solomon, NOAA; and Thomas Wilbanks, DOE Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Other contributors: Eastern Research Group (ERG) assisted with document editing and formatting. Stratus Consulting also assisted with document editing and formatting. ii Table of Contents Executive Summary..............................................................................................................ES-1 I. Introduction 1. Introduction and Background ..................................................................................................... 2 a. Scope and Approach of This Document.................................................................................... 2 b. -

The Global Warming Potential Is Inconsistent with the Physics of Climate Change and Misrepresents the Effects of Policy Interventions

https://www.essoar.org/doi/10.1002/essoar.10504991.1 Poster SY012-0005 The Global Warming Potential is Inconsistent with the Physics of Climate Change and Misrepresents the Effects of Policy Interventions Robert L. Kleinberg Boston University Institute for Sustainable Energy https://www.essoar.org/doi/10.1002/essoar.10504991.1 METHANE AS AN ENERGY SOURCE AND A GREENHOUSE GAS SUMMARY: Methane, the primary component of natural gas, is both a useful primary source of energy and a powerful greenhouse gas. It is as important as carbon dioxide in determining whether we meet our 2050 climate goals. --------------- Natural gas (blue bars) is the most versatile source of primary energy in the US energy system, serving power, residential, commercial, and industrial sectors. https://www.essoar.org/doi/10.1002/essoar.10504991.1 Natural gas plays a unique role in energy storage. Every winter it feeds about 500 terawatt- hours of energy into power and heating systems. There is no other energy storage system that has anywhere near this capability, in overall capacity and ability to store energy for seasonal use. https://www.essoar.org/doi/10.1002/essoar.10504991.1 The primary constituent (90-95%) of pipeline grade natural gas is methane, which when emitted directly to the atmosphere is a powerful greenhouse gas. Globally, about half of methane emissions are from natural sources (green segments) and the other half are anthropogenic (other colors). https://www.essoar.org/doi/10.1002/essoar.10504991.1 Methane is 120 times more powerful as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, on a per- kilogram basis. -

Using a Life Cycle Assessment Approach to Estimate the Net Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Bioenergy

Using a Life Cycle Assessment Approach to Estimate the Net This strategic report was prepared by Mr Neil Bird, Joanneum Greenhouse Gas Research, Austria; Professor Annette Cowie, The National Emissions of Centre for Rural Greenhouse Gas Research, Australia; Dr Francesco Bioenergy Cherubini, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway; and Dr Gerfried Jungmeier; Joanneum Research, Austria. The report addresses the key methodological aspects of life cycle assessment (LCA) with respect to greenhouse gas (GHG) balances of bioenergy systems. It includes results via case studies, for some important bioenergy supply chains in comparison to fossil energy systems. The purpose of the report is to produce an unbiased, authoritative statement aimed especially at practitioners, policy advisors, and policy makers. IEA Bioenergy IEA Bioenergy:ExCo:2011:03 1 Using a Life Cycle assessMent approaCh to estiMate the net greenhoUse gas Emissions of Bioenergy authors: Mr Neil Bird (Joanneum Research, Austria), Professor Annette Cowie (The National Centre for Rural Greenhouse Gas Research, Australia), Dr Francesco Cherubini (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway) and Dr Gerfried Jungmeier (Joanneum Research, Austria). Key Messages 1. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is used to quantify the environmental impacts of products or services. It includes all processes, from cradle-to-grave, along the supply chain of the product or service. When analysing the global warming impact of energy systems, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (particularly CO2, CH4, and N2O) are of primary concern. 2. To determine the comparative GHG impacts of bioenergy, the bioenergy system being analysed should be compared with a reference energy system, e.g. a fossil energy system. -

4.6 Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change

4. Environmental Setting, Impacts, and Mitigation Measures 4.6 Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change It is widely recognized that emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) associated with human activities are contributing to changes in the global climate, and that such changes are having and will continue to have adverse effects on the environment, the economy, and public health. These are the cumulative effects of past, present, and future actions worldwide. While worldwide contributions of GHGs are expected to have widespread consequences, it is not possible to link particular changes to the environment of California to GHGs emitted from a particular source or location. Thus, when considering a project’s contribution to impacts from climate change, it is possible to examine the quantity of GHGs that would be emitted either directly from project sources or indirectly from other sources, such as production of electricity. However, that quantity cannot be tied to a particular adverse effect on the environment of California associated with climate change. 4.6.1 Environmental Setting Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere are called greenhouse gases (GHGs). The major concern with GHGs is that increases in their concentrations are causing global climate change. Global climate change is a change in the average weather on earth that can be measured by wind patterns, storms, precipitation, and temperature. Although there is disagreement as to the speed of global warming and the extent of the impacts attributable to human activities, most agree that there is a direct link between increased emissions of GHGs and long term global temperature increases. What GHGs have in common is that they allow sunlight to enter the atmosphere, but trap a portion of the outward-bound infrared radiation which warms the air. -

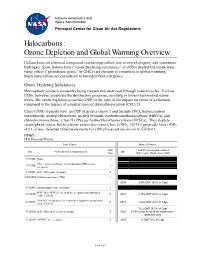

Halocarbons: Ozone Depletion and Global Warming Overview

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Principal Center for Clean Air Act Regulations Halocarbons: Ozone Depletion and Global Warming Overview Halocarbons are chemical compounds containing carbon, one or more halogens, and sometimes hydrogen. Some halocarbons (“ozone depleting substances,” or ODSs) deplete the ozone layer, while others (“greenhouse gases,” or GHGs) are thought to contribute to global warming. Many halocarbons are considered to belong to both categories. Ozone Depleting Substances Stratospheric ozone is constantly being created and destroyed through natural cycles. Various ODSs, however, accelerate the destruction processes, resulting in lower-than-normal ozone levels. The ozone depletion potential (ODP) is the ratio of the impact on ozone of a chemical compared to the impact of a similar mass of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) 11. Class I ODSs typically have an ODP of greater than 0.1 and include CFCs, halons, carbon tetrachloride, methyl chloroform, methyl bromide, hydrobromofluorocarbons (HBFCs), and chlorobromomethane. Class II ODSs are hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs). They deplete stratospheric ozone, but to a lesser extent than most Class I ODSs. HCFCs generally have ODPs of 0.1 or less. Selected timeline elements for ODS phase-out are shown in Exhibit 1. EXHIBIT 1 ODS Phase-out Timeline United States Montreal Protocol ODS US HCFC Consumption Allowed Date No Production or Importation of: Date Class ODP-weighted Metric Tons (OMT) 1/1/1994 Halons I CFCs, carbon tetrachloride, methyl chloroform, HBFCs (some 1/1/1996