Using a Life Cycle Assessment Approach to Estimate the Net Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Bioenergy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic and Policy Factors Driving Adoption of Institutional Woody Biomass Heating Systems in the U.S.☆

Energy Economics 69 (2018) 456–470 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Energy Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/eneeco Economic and policy factors driving adoption of institutional woody biomass heating systems in the U.S.☆ Jesse D. Young a,⁎,1, Nathaniel M. Anderson b, Helen T. Naughton c, Katrina Mullan c a School of Forestry, Northern Arizona University, 200 East Pine Knoll Drive, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, United States b Forestry Sciences Lab, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Forest Service, 800 East Beckwith, Missoula, MT 59802, United States c Department of Economics, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812-5472, United States article info abstract Article history: Abundant stocks of woody biomass that are associated with active forest management can be used as fuel for Received 16 September 2015 bioenergy in many applications. Though factors driving large-scale biomass use in industrial settings have Received in revised form 26 August 2017 been studied extensively, small-scale biomass combustion systems commonly used by institutions for heating Accepted 23 November 2017 have received less attention. A zero inflated negative binomial (ZINB) model is employed to identify economic Available online xxxx and policy factors favorable to installation and operation of these systems. This allows us to determine the effec- tiveness of existing policies and identify locations where conditions offer the greatest potential for additional JEL classification: L73 promotion of biomass use. Adoption is driven by heating needs, fossil fuel prices, and proximity to woody bio- L78 mass resources, specifically logging residues, National Forests, and fuel treatments under the National Fire Plan. Q23 Published by Elsevier B.V. -

The Putney School Master Plan May 2019

The Putney School Master Plan May 2019 Preface | 1 Putney School Master Plan | May 2019 Preface | 2 The Putney School Master Plan May 2019 Updated from December 2011 2019 Campus Masterplanning Committee Emily Jones, Head of School Hugh Montgomery, Director of Development Dawn Zweig, Science Teacher Mark Grieco, Plant Manager Josh Laughlin ‘82, Board Chair Pete Stickney, Farm Manager Randy Smith, Assistant Head of School/CFO Student Representatives Cam Anderson ‘19 Oli Castillo ‘19 Izzy Snyder ‘19 Jules Fisher-White ‘19 Li Ding ‘19 Consultants Maclay Architects Energy Balance, Inc. DEW Construction Corp. Stevens & Associates, P.C. Additional consultants for the 2011 Master Plan: Don Hirsch Design Studio, LLC Lyssa Papazian Future Generations Forestry Preface | i Putney School Master Plan | May 2019 Preface | ii Contents Introduction v4. The Built Environment 15 Describes the structures on The Putney School campus and how they are used, and the circulation patterns vii Executive Summary for both pedestrians and vehicles across the campus Overview of Master Plan Implementation landscape. 4.1 Overall Campus Space Use 15 4.2 Gathering Spaces 19 4.3 Transportation, Circulation and Parking 20 1. Master Plan Background 1 Provides a brief profile of The Putney School and its regional context, a description of the Master 5. The Campus Plan 23 Planning process, and an explanation of the goals on Lays out programmatic recommendations for the this project. built and natural environment. This section identifies 1.1 Mission and Context 1 facilities that need to be re-envisioned to better serve 1.2 Master Plan Concept 2 the needs of the student body. -

Methane Emissions from Forests Ecosystems Enhance Global Warming? : Keppler Et.Al.(2006)

Methane emissions from forests ecosystems enhance global warming? : Keppler et.al.(2006). Methane emissions from terrestrial plants under aerobic conditions. Nature 439: 187-191 Quantifications of possible effects and comments Summary The results of this study could affect attractiveness and returns of CDM carbon offset projects and future negotiations about carbon sinks in the second commitment period. If confirmed independently, they represent a paradigm shift regarding methane formation in plant physiology. When extrapolated, net greenhouse gas removals by growing forests, e.g. existing forests or forests created by afforestation projects under the Clean Development Mechanism, could be reduced by maximally 4-8% though aerobic emissions of methane by trees. Net actual effects are likely to be lower. However, transposing and up-scaling results obtained in containers on small samples, seedlings, and on only one tree species to global forests and other biomes is not a valid “first estimate”, but at best a hypothesis which should be tested. Results do not invalidate the role of forests as carbon sinks; they also do not support the view that deforestation mitigates global warming via reduced emissions of methane. Background The paper postulates a sizeable, previously unknown methane source of 60-240 Mt from forests and other biomes, and an additional source of 1-7 Mt CH4 from litter. Plant physiology has up to now not recognized the possibility of aerobic methane formation by intact plants or litter. Methane, a powerful greenhouse gas with a global warming potential of 23 times that of CO2, has been thought to originate in rice patties, natural wetlands, landfills, natural gas reservoirs, biomass burning and in the digestive tracts of cattle.If these methane emissions can be corroborated, the discovery amounts to a paradigm shift in plant physiology. -

Synthetic Greenhouse Gases

Synthetic Greenhouse Gases How are they different to What are ‘synthetic greenhouse gases’? ‘greenhouse gases’? Synthetic greenhouse gases are man made Greenhouse gases are naturally occurring. chemicals. They are commonly used in They include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane refrigeration and air conditioning, fire (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Synthetic extinguishing, foam production and in greenhouse gases are man made chemicals medical aerosols. When they are released, and generally have a much higher global synthetic greenhouse gases trap heat in warming potential than naturally occurring the atmosphere. greenhouse gases. What is global warming potential? Global warming potential (GWP) is a measure of how much heat a greenhouse gas traps in the atmosphere over a specific time compared to a similar mass of carbon dioxide (CO2). CO2, with a global warming potential of 1, is used as the base figure for measuring global warming potential. The higher the global warming potential number, the more heat a gas traps. The most common synthetic greenhouse gas in Australia is HFC-134a, which is mostly used in refrigerators and air conditioners. It has a global warming potential of 1430; this means the release of one tonne of HFC-134a is equivalent to releasing 1430 tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. Which synthetic greenhouse gases does 22,800 Australia regulate? SF6 the global warming potential of sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) • hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) • perfluorocarbons (PFCs) • sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) Synthetic • nitrogen trifluoride (NF3) greenhouse gases account for around 2% of all greenhouse gas emissions in Australia How do we use synthetic greenhouse gases? They are man made chemicals with a wide variety of uses. -

Accounting for the Climate–Carbon Feedback in Emission Metrics

Earth Syst. Dynam., 8, 235–253, 2017 www.earth-syst-dynam.net/8/235/2017/ doi:10.5194/esd-8-235-2017 © Author(s) 2017. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Accounting for the climate–carbon feedback in emission metrics Thomas Gasser1,2,a, Glen P. Peters2, Jan S. Fuglestvedt2, William J. Collins3, Drew T. Shindell4, and Philippe Ciais1 1Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, LSCE/IPSL, Université Paris-Saclay, CEA – CNRS – UVSQ, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 2Center for International Climate and Environmental Research – Oslo (CICERO), 0349 Oslo, Norway 3Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, Reading, RG6 6BB, UK 4Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA anow at: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), 2361 Laxenburg, Austria Correspondence to: Thomas Gasser ([email protected]) Received: 4 November 2016 – Discussion started: 10 November 2016 Accepted: 20 March 2017 – Published: 10 April 2017 Abstract. Most emission metrics have previously been inconsistently estimated by including the climate– carbon feedback for the reference gas (i.e. CO2) but not the other species (e.g. CH4). In the fifth assessment report of the IPCC, a first attempt was made to consistently account for the climate–carbon feedback in emission metrics. This attempt was based on only one study, and therefore the IPCC concluded that more research was needed. Here, we carry out this research. First, using the simple Earth system model OSCAR v2.2, we establish a new impulse response function for the climate–carbon feedback. Second, we use this impulse response func- tion to provide new estimates for the two most common metrics: global warming potential (GWP) and global temperature-change potential (GTP). -

Fossil Foodscapes: Examining the United States' Carbon Diet

FOSSIL FOODSCAPES: EXAMINING THE UNITED STATES’ CARBON DIET by SIENA POLK A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2020 An Abstract of the Thesis of Siena Polk for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of International Studies to be taken June 2020 Title: Fossil Foodscapes: Examining the United States’ Carbon Diet Approved: _______________________________________ Dr. Galen Martin While many are aware of the inputs required to maintain food production at an industrial level in the United States, we seldom reflect on the profound significance of a food system that is so deeply rooted in what Matthew Huber calls the “dead ecologies of fossilized energy.” In order to more fully understand and critique the linkages between fossil fuels and agriculture, as well as their ecological and social implications, I examine the use of fossil fuels in agriculture through an eco-socialist framework. I employ Wim Carton’s fossil fuel landscape and Marx as developed by John Bellamy Foster’s concept of metabolic rift to illuminate the linkages between combustible carbons and the food we eat. Ultimately, these two concepts lead to a place of critical understanding in attempts to envision a more sustainable and resilient future. Such an inquiry is of the upmost urgency considering the dual threats of climate change and soil erosion. Both threats are exacerbated by our continued use of fossil fuels and the machines they power. ii iii Acknowledgements This thesis was written on Kalapuya land. -

A Long Food Movement

A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045 Lead authors: Pat Mooney, Nick Jacobs, Veronica Villa, Jim Thomas, Marie-Hélène Bacon, Louise Vandelac, and Christina Schiavoni. Advisory Group: Molly Anderson, Bina Agarwal, Million Belay, Jahi Chappell, Jennifer Clapp, Fabrice DeClerck, Matthew Dillon, Maria Alejandra Escalante, Ana Felicien, Emile Frison, Steve Gliessman, Mamadou Goïta, Shalmali Guttal, Hans Herren, Henk Hobbelink, Lim Li Ching, Sue Longley, Raj Patel, Darrin Qualman, Laura Trujillo-Ortega, and Zoe VanGelder. This text was approved by the IPES-Food panel and by ETC Group in March 2021. Citation: IPES-Food & ETC Group, 2021. A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045. 2 Acknowledgements The lead authors were responsible for the development and drafting of this report through their participation in a Management Committee, under the leadership of Nick Jacobs (IPES- Food Director) and Pat Mooney (Project Lead, IPES-Food panel member and ETC Group co-founder). Research and editorial work was ably assisted by Anna Paskal in the final stages. Throughout the project, the Management Committee has been guided by the contributions of a 21-member Advisory Group, drawn from various world regions and civil society constituencies (including Indigenous peoples, peasant organizations, food workers, and youth climate activists) as well as from multilateral institutions, many scientific disciplines, and business. Although these experts have contributed extensively to guiding the analysis, their participation in the Advisory Group does not imply full validation of the report or specific ideas therein. The management committee would like to thank Advisory Group members for their invaluable commitment and expertise. They are also grateful to the full IPES-Food panel, which has played a key role in shaping and developing this project, and the full ETC Group team for their many research and review contributions, especially Neth Daño and Zahra Moloo. -

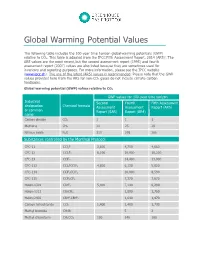

Global Warming Potential Values

Global Warming Potential Values The following table includes the 100-year time horizon global warming potentials (GWP) i relative to CO2. This table is adapted from the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, 2014 (AR5) . The AR5 values are the most recent, but the second assessment report (1995) and fourth assessment report (2007) values are also listed because they are sometimes used for inventory and reporting purposes. For more information, please see the IPCC website (www.ipcc.ch). The use of the latest (AR5) values is recommended. Please note that the GWP values provided here from the AR5 for non-CO2 gases do not include climate-carbon feedbacks. Global warming potential (GWP) values relative to CO2 GWP values for 100-year time horizon Industrial Second Fourth Fifth Assessment designation Chemical formula Assessment Assessment Report (AR5) or common Report (SAR) Report (AR4) name Carbon dioxide CO2 1 1 1 Methane CH4 21 25 28 Nitrous oxide N2O 310 298 265 Substances controlled by the Montreal Protocol CFC-11 CCl3F 3,800 4,750 4,660 CFC-12 CCl2F2 8,100 10,900 10,200 CFC-13 CClF3 14,400 13,900 CFC-113 CCl2FCClF2 4,800 6,130 5,820 CFC-114 CClF2CClF2 10,000 8,590 CFC-115 CClF2CF3 7,370 7,670 Halon-1301 CBrF3 5,400 7,140 6,290 Halon-1211 CBrClF2 1,890 1,750 Halon-2402 CBrF2CBrF2 1,640 1,470 Carbon tetrachloride CCl4 1,400 1,400 1,730 Methyl bromide CH3Br 5 2 Methyl chloroform CH3CCl3 100 146 160 GWP values for 100-year time horizon Industrial Second Fourth Fifth designation Chemical formula assessment Assessment Assessment or common report (SAR) -

Sustainable Energy Based on Sunflower Seed Husk Boiler For

sustainability Article Sustainable Energy Based on Sunflower Seed Husk Boiler for Residential Buildings Miguel-Angel Perea-Moreno 1,* , Francisco Manzano-Agugliaro 2 and Alberto-Jesus Perea-Moreno 1 1 Departamento de Física Aplicada, Universidad de Córdoba, ceiA3, Campus de Rabanales, 14071 Córdoba, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Engineering, University of Almeria, ceiA3, 04120 Almeria, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-957-212-633 Received: 13 September 2018; Accepted: 20 September 2018; Published: 25 September 2018 Abstract: Buildings account for one third of the world’s energy consumption, 70% of which is devoted to heating and cooling. To increase the share of renewables in the energy consumption of buildings, it is necessary to research and promote new sources of green energy. World production of sunflower (Helianthus annuus) was 47.34 million tons in 2016, with a harvested area of 26.20 million hectares, and the main producing countries being Ukraine, the Russian Federation, and Argentina, which produce about half of world production of sunflower seed. The sunflower husk, which represents a percentage by weight of 45%–60% of the seed depending on the sunflower variety, is widely used for the production of feed; however, its energy use is very scarce. The objectives of this study were to analyse the energy properties of sunflower husk as a solid biofuel and to carry out an energy, environmental, economic and operational analysis of a thermal installation fed with this by-product of the sunflower oil industry. The results show that this agro-industrial waste has a Higher Heating Value (HHV) of 17.844 MJ/kg, similar to that of other solid biofuels currently used. -

Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2015

ANNEX 6 Additional Information 6.1. Global Warming Potential Values Global Warming Potential (GWP) is intended as a quantified measure of the globally averaged relative radiative forcing impacts of a particular greenhouse gas. It is defined as the cumulative radiative forcing–both direct and indirect effectsintegrated over a specific period of time from the emission of a unit mass of gas relative to some reference gas (IPCC 2007). Carbon dioxide (CO2) was chosen as this reference gas. Direct effects occur when the gas itself is a greenhouse gas. Indirect radiative forcing occurs when chemical transformations involving the original gas produce a gas or gases that are greenhouse gases, or when a gas influences other radiatively important processes such as the atmospheric lifetimes of other gases. The relationship between kilotons (kt) of a gas and million metric tons of CO2 equivalents (MMT CO2 Eq.) can be expressed as follows: MMT MMT CO2 Eq. kt of gas GWP 1,000 kt where, MMT CO2 Eq. = Million metric tons of CO2 equivalent kt = kilotons (equivalent to a thousand metric tons) GWP = Global warming potential MMT = Million metric tons GWP values allow policy makers to compare the impacts of emissions and reductions of different gases. According to the IPCC, GWP values typically have an uncertainty of 35 percent, though some GWP values have larger uncertainty than others, especially those in which lifetimes have not yet been ascertained. In the following decision, the parties to the UNFCCC have agreed to use consistent GWP values from the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4), based upon a 100 year time horizon, although other time horizon values are available (see Table A-263). -

Greenhouse Gas and Global Warming Potential Excerpt from U.S. National Emissions Inventory

GREENHOUSE GASES AND GLOBAL WARMING POTENTIAL VALUES EXCERPT FROM THE INVENTORY OF U.S. GREENHOUSE EMISSIONS AND SINKS: 1990-2000 U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Program Office of Atmospheric Programs U.S. Environmental Protection Agency April 2002 Greenhouse Gases and Global Warming Potential Values Original Reference All material taken from the Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990 - 2000, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Atmospheric Programs, EPA 430-R-02- 003, April 2002. <www.epa.gov/globalwarming/publications/emissions> How to Obtain Copies You may electronically download this document from the U.S. EPA’s Global Warming web page on at: www.epa.gov/globalwarming/publications/emissions For Further Information Contact Mr. Michael Gillenwater, Office of Air and Radiation, Office of Atmospheric Programs, Tel: (202)564-0492, or e-mail [email protected] Acknowledgments The preparation of this document was directed by Michael Gillenwater. The staff of the Climate and Atmospheric Policy Practice at ICF Consulting, especially Marian Martin Van Pelt and Katrin Peterson deserve recognition for their expertise and efforts in supporting the preparation of this document. Excerpt from Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2000 Page 2 Greenhouse Gases and Global Warming Potential Values Introduction The Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions elements of the Earth’s climate system. Natural and Sinks presents estimates by the United States processes such as solar-irradiance variations, government of U.S. anthropogenic greenhouse variations in the Earth’s orbital parameters, and gas emissions and removals for the years 1990 volcanic activity can produce variations in through 2000. -

Global Warming Potential (GWP) of Refrigerants: Why Are Particular Values Used?

OZONACTION FACT SHEET Global Warming Potential (GWP) of Refrigerants: Why are Particular Values Used? INTRODUCTION Ever since the Montreal Protocol agreed to phase out hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), there has been an increasing interest within the Protocol on climate issues. The now famous Decision XIX/6, taken in 2007, to adjust the Protocol to accelerate the phase out of HCFCs includes language to encourage the promotion of alternatives that minimise environmental impacts, in particular impacts on climate, as well as to prioritise funding for projects, inter alia, which focus on substitutes and alternatives that minimise other impacts on the environment, ©Shutterstock including on the climate, taking into account global- warming potential (GWP). In your work you may come across various GWP Current discussions on the Montreal Protocol figures from technical experts, industry and other potentially being amended to facilitate the phase- stakeholders which may not appear to be down of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) bring the issue consistent. This could be due to the fact that the of climate change and associated monitoring and values quoted are from different sources or reporting to the forefront of the Protocol. different sets of GWP values. WHAT IS GWP? Global warming potential (GWP) is a measure of the The higher the GWP value, the more that particular relative global warming effects of different gases. It gas warms the Earth compared to carbon dioxide. assigns a value to the amount of heat trapped by a certain mass of a gas relative to the amount of heat GWP values for ozone depleting substances can trapped by a similar mass of carbon dioxide over a range, for example, from 2 up to about 14,000.