Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research Paper 40 January 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia Page 1 of 16

Zambia Page 1 of 16 Zambia Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003 Zambia is a republic governed by a president and a unicameral national assembly. Since 1991 generally free and fair multiparty elections have resulted in the victory of the Movement for Multi -Party Democracy (MMD). In December 2001, Levy Mwanawasa of the MMD was elected president, and his party won 69 out of 150 elected seats in the National Assembly. The MMD's use of government resources during the campaign raised questions over the fairness of the elections. Although noting general transparency during the voting, domestic and international observer groups cited irregularities in the registration process and problems in the tabulation of the election results. Opposition parties challenged the election result in court, and court proceedings remained ongoing at year's end. The Constitution mandates an independent judiciary, and the Government generally respected this provision; however, the judicial system was hampered by lack of resources, inefficiency, and reports of possible corruption. The police, divided into regular and paramilitary units operated under the Ministry of Home Affairs, had primary responsibility for maintaining law and order. The Zambia Security and Intelligence Service (ZSIS), under the Office of the President, was responsible for intelligence and internal security. Members of the security forces committed numerous, and at times serious, human rights abuses. Approximately 60 percent of the labor force worked in agriculture, although agriculture contributed only 22 percent to the gross domestic product. Economic growth slowed to 3 percent for the year, partly as a result of drought in some agricultural areas. -

Post-Populism in Zambia: Michael Sata's Rise

This is the accepted version of the article which is published by Sage in International Political Science Review, Volume: 38 issue: 4, page(s): 456-472 available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512117720809 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/24592/ Post-populism in Zambia: Michael Sata’s rise, demise and legacy Alastair Fraser SOAS University of London, UK Abstract Models explaining populism as a policy response to the interests of the urban poor struggle to understand the instability of populist mobilisations. A focus on political theatre is more helpful. This article extends the debate on populist performance, showing how populists typically do not produce rehearsed performances to passive audiences. In drawing ‘the people’ on stage they are forced to improvise. As a result, populist performances are rarely sustained. The article describes the Zambian Patriotic Front’s (PF) theatrical insurrection in 2006 and its evolution over the next decade. The PF’s populist aspect had faded by 2008 and gradually disappeared in parallel with its leader Michael Sata’s ill-health and eventual death in 2014. The party was nonetheless electorally successful. The article accounts for this evolution and describes a ‘post-populist’ legacy featuring hyper- partisanship, violence and authoritarianism. Intolerance was justified in the populist moment as a reflection of anger at inequality; it now floats free of any programme. Keywords Elections, populism, political theatre, Laclau, Zambia, Sata, Patriotic Front Introduction This article both contributes to the thin theoretic literature on ‘post-populism’ and develops an illustrative case. It discusses the explosive arrival of the Patriotic Front (PF) on the Zambian electoral scene in 2006 and the party’s subsequent evolution. -

Intra-Party Democracy in the Zambian Polity1

John Bwalya, Owen B. Sichone: REFRACTORY FRONTIER: INTRA-PARTY … REFRACTORY FRONTIER: INTRA-PARTY DEMOCRACY IN THE ZAMBIAN POLITY1 John Bwalya Owen B. Sichone Abstract: Despite the important role that intra-party democracy plays in democratic consolidation, particularly in third-wave democracies, it has not received as much attention as inter-party democracy. Based on the Zambian polity, this article uses the concept of selectocracy to explain why, to a large extent, intra-party democracy has remained a refractory frontier. Two traits of intra-party democracy are examined: leadership transitions at party president-level and the selection of political party members for key leadership positions. The present study of four political parties: United National Independence Party (UNIP), Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), United Party for National Development (UPND) and Patriotic Front (PF) demonstrates that the iron law of oligarchy predominates leadership transitions and selection. Within this milieu, intertwined but fluid factors, inimical to democratic consolidation but underpinning selectocracy, are explained. Keywords: Intra-party Democracy, Leadership Transition, Ethnicity, Selectocracy, Third Wave Democracies Introduction Although there is a general consensus that political parties are essential to liberal democracy (Teorell 1999; Matlosa 2007; Randall 2007; Omotola 2010; Ennser-Jedenastik and Müller 2015), they often failed to live up to the expected democratic values such as sustaining intra-party democracy (Rakner and Svasånd 2013). As a result, some scholars have noted that parties may therefore not necessarily be good for democratic consolidation because they promote private economic interests, which are inimical to democracy and state building (Aaron 1 The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments from the editorial staff and anonymous reviewers. -

What Drives Input Subsidy Policy Reform? the Case of Zambia, 2002–2016

IFPRI Discussion Paper 01572 November 2016 What Drives Input Subsidy Policy Reform? The Case of Zambia, 2002–2016 Danielle Resnick Nicole M. Mason Development Strategy and Governance Division INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), established in 1975, provides evidence-based policy solutions to sustainably end hunger and malnutrition, and reduce poverty. The institute conducts research, communicates results, optimizes partnerships, and builds capacity to ensure sustainable food production, promote healthy food systems, improve markets and trade, transform agriculture, build resilience, and strengthen institutions and governance. Gender is considered in all of the institute’s work. IFPRI collaborates with partners around the world, including development implementers, public institutions, the private sector, and farmers’ organizations, to ensure that local, national, regional, and global food policies are based on evidence. AUTHORS Danielle Resnick ([email protected]) is a senior research fellow in the Development Strategy and Governance Division of the International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC. Nicole M. Mason ([email protected]) is an assistant professor in the Department of Agriultural, Food, and Resource Economics at Michigan State Univeristy, East Lansing, MI, US. Notices 1. IFPRI Discussion Papers contain preliminary material and research results and are circulated in order to stimulate discussion and critical comment. They have not been subject to a formal external review via IFPRI’s Publications Review Committee. Any opinions stated herein are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily representative of or endorsed by the International Food Policy Research Institute. 2. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on the map(s) herein do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) or its partners and contributors. -

Members of the Northern Rhodesia Legislative Council and National Assembly of Zambia, 1924-2021

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA Parliament Buildings P.O Box 31299 Lusaka www.parliament.gov.zm MEMBERS OF THE NORTHERN RHODESIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL AND NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA, 1924-2021 FIRST EDITION, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................ 3 PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 5 ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 9 PART A: MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, 1924 - 1964 ............................................... 10 PRIME MINISTERS OF THE FEDERATION OF RHODESIA .......................................................... 12 GOVERNORS OF NORTHERN RHODESIA AND PRESIDING OFFICERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) ............................................................................................... 13 SPEAKERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) - 1948 TO 1964 ................................. 16 DEPUTY SPEAKERS OF THE LEGICO 1948 TO 1964 .................................................................... -

The Principle 'One Zambia, One Nation': Fifty Years Later

The Principle ‘One Zambia, One Nation’: Fifty Years Later Lyubov Ya. Prokopenko Institute for African Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow ABSTRACT In the first years of independence, United National Independence Par- ty (UNIP) and President of Zambia Kenneth Kaunda, realizing that Zambia as a young multi-ethnic state can develop only assuming nor- mal relations between its 73 ethnic groups, proclaimed the slogan ‘One Zambia is One People’ as the basic principle of nation-building. The formation of a young nation should also be facilitated by the in- troduction of the principle of regional and ethnic balancing – quotas for various ethnic groups for representation in government bodies. Under the conditions of political pluralism since 1991, power in Zam- bia was transferred peacefully, including after the victory of the oppo- sition in the elections in 2011. Zambia is often called a successful ex- ample of achieving ethno-political consolidation in a multi-ethnic Af- rican state, which can be regarded as a certain success in the for- mation of a national state. The new president Edgar Lungu re-elected in September 2016 declares that the policy of his government and of the PF party will be firmly based on the inviolability of the principle ‘One Zambia – One Nation’. INTRODUCTION On October 23, 2014, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Zam- bia's independence, the national bank issued a commemorative 50 kwacha banknote (for the first time as legal means of payment) which portrays all the presidents of Zambia: Kenneth Kaunda, Freder- ick Chiluba, Levy Mwanawasa, Rupiah Banda and Michael Sata. -

Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research Paper 28 October 2016

Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research Paper 28 October 2016 WHAT DRIVES INPUT SUBSIDY POLICY REFORM? THE CASE OF ZAMBIA, 2002-2016 By Danielle Resnick and Nicole Mason Food Security Policy Research Papers This Research Paper series is designed to timely disseminate research and policy analytical outputs generated by the USAID funded Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy (FSP) and its Associate Awards. The FSP project is managed by the Food Security Group (FSG) of the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) at Michigan State University (MSU), and implemented in partnership with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the University of Pretoria (UP). Together, the MSU-IFPRI-UP consortium works with governments, researchers and private sector stakeholders in Feed the Future focus countries in Africa and Asia to increase agricultural productivity, improve dietary diversity and build greater resilience to challenges like climate change that affect livelihoods. The papers are aimed at researchers, policy makers, donor agencies, educators, and international development practitioners. Selected papers will be translated into French, Portuguese, or other languages. Copies of all FSP Research Papers and Policy Briefs are freely downloadable in pdf format from the following Web site: www.foodsecuritylab.msu.edu Copies of all FSP papers and briefs are also submitted to the USAID Development Experience Clearing House (DEC) at: http://dec.usaid.gov/ ii AUTHORS Danielle Resnick ([email protected]) is a Senior Research Fellow, Development Strategies and Governance Division, at the International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC. Nicole Mason ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics at Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, US. -

PEN Zambia and PEN International Contribution to the 28Th Session Of

PEN Zambia and PEN International Contribution to the 28th session of the Working Group of the Universal Periodic Review Submission on Zambia 30 March 2017 I. INTRODUCTION 1. PEN Zambia and PEN International welcome the opportunity to contribute to the third cycle of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Zambia. This submission focuses on the situation of the right to freedom of expression and association in Zambia in the period November 2012 to March 2017. II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2. During the 2012 UPR process, Zambia received four recommendations in regards to freedom of expression and freedom of assembly, of which they accepted one from the United States, thereby committing to “ensure that the freedoms of assembly and expression are upheld and [to] respect the 2003 Supreme Court ruling stating that these freedoms are fundamental”1. 3. Zambia also noted the recommendations made by Iraq, Ireland and the United Kingdom, related respectively to calling for the repeal of laws limiting freedom of expression in the media; ensuring that the legal system is in full compliance with its international obligations in respect of freedom of expression and that media and journalists are able to freely carry out their work; and calling for the amendment of the Public Order Act in order to ensure the fullest possible freedoms of association and expression.2 1 “Ensure that the freedoms of assembly and expression are upheld and respect the 2003 Supreme Court ruling stating that these freedoms are fundamental.” (United States) Available at: https://www.upr- info.org/database/index.php?limit=0&f_SUR=193&f_SMR=All&order=&orderDir=ASC&orderP=true&f_Issu e=All&searchReco=&resultMax=300&response=&action_type=&session=&SuRRgrp=&SuROrg=&SMRRgrp =&SMROrg=&pledges=RecoOnly ; 2003 Supreme Court ruling, ‘Resident Doctors Association Of Zambia and Others VS The Attorney General,’ Supreme Court Sakala, CJ, Lewanika, DCJ, and Mambilima, JJS 26th September, 2002 and 28th October, 2003 (SCZ Judgment No. -

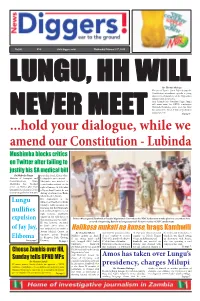

Hold Your Dialogue, While We Amend Our Constitution

No380 K10 www.diggers.news Wednesday February 27, 2019 LUNGU, HH WILLBy omas Mulenga Minister of Justice Given Lubinda says the Constitution amendment agenda is going ahead even if members of the Opposition Alliance shun the process. And Lubinda says President Edgar Lungu will never meet his UPND counterpart Hakainde Hichilema again, since the latter has accused the Head of State of plotting to NEVER MEET assassinate him. To page 5 ...hold your dialogue, while we amend our Constitution - Lubinda Mushimba blocks critics on Twitter after failing to justify his SA medical bill By Mukosha Funga treated in South Africa, where Minister of Transport and he stayed for over a month. Communications Brian Mushimba was involved in Mushimba has blocked a road tra c accident on the critics on Twitter a er they night of January 18, 2019 a er demanded justi cation for his a Toyota Land Cruiser he was decision to get his broken arm driving overturned on abo Mbeki Road in Lusaka. His counterpart at the Lungu Ministry of Health, Dr Chitalu Chilufya, told journalists the following day that Mushimba nulli es had sustained injuries to his right forearm, underwent surgery in the early hours of expulsion that morning and was stable”. Police o cers guard Kambwili at Lusaka Magistrate’s Cour where the NDC leader went to take plea in a case where he is He was, however, evacuated accused of expressing hate for a foreign national- Picture courtesy of NDC media team to South Africa where he of Jay Jay, was hospitalised for weeks at Arwyp Medical Centre, an Nalikosa mukati na kunse, brags Kambwili By Zondiwe Mbewe contempt for persons because 19, this year, expressed racial the viral social media video in expensive private hospital Nalikosa mukati na kunse of race contrary to section remarks on Rajesh Kumar which he was lmed having Eliboma in Kempton Park, Gauteng (I am strong inside and 70(1) of the penal code chapter Verma, an Indian national. -

Access to Information Law Published Article-1.Pdf

Communicatio South African Journal for Communication Theory and Research ISSN: 0250-0167 (Print) 1753-5379 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcsa20 Access to information law and the stalled ‘winds of change’ in zambia Sam Phiri To cite this article: Sam Phiri (2016) Access to information law and the stalled ‘winds of change’ in zambia, Communicatio, 42:1, 35-55 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02500167.2016.1152991 Published online: 17 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcsa20 Download by: [Sam Phiri] Date: 17 March 2016, At: 14:38 ACCESS TO INFORMATION LAW AND THE STALLED ‘WINDS OF CHANGE’ IN ZAMBIA Sam Phiri Department of Mass Communication University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia [email protected] ABSTRACT Zambia, like a few other African countries, has been grappling with the adoption of the Access to Information (ATI) law over the past 25 years. This article argues that the Zambian approach towards easing access to public information has been faulty, because it is narrowly focused and this has resulted in the process stalling. The argument is made here, that the ATI law is part of a global social movement towards greater transparency. Furthermore, the article focuses on Zambia’s approach to the law (whose push is dominated by executive control) Downloaded by [Sam Phiri] at 14:38 17 March 2016 and how that approach has impacted on good governance. -

We Want Change!

Zambia Weekly Week 38, Volume 2, Issue 37, 23 September 2011 In this issue We want change! We want change! 1 Dementia: When politics take hostages 2 Quotes 2 2011 elections report: 3 tense days 3 Who is your new MP? 3 Elections - according to the world 7 Mahtani mourns sale of “his” bank 8 Albidon: We don’t trust you 8 LuSE week-on-week 8 Zambia commemorates Hammerskjold 9 The EU responds to editorial 9 Zambia plunged into darkness 9 Editor’s note Zambia has just completed its fifth Image by Agence France-Presse/Getty Images general elections since multi-party democracy was re-introduced in 1991 – and demonstrated how to hand And their cries were finally answered! Zambia is about to undergo regime change. The PF over the political mantle in a rela- boat has docked. The opposition PF party’s Michael Sata has won the 2011 presidential elec- tively peaceful manner (see page 3-7), tion, putting a stop to MMD’s 20 years in power. which is worth applauding! Now that In the early hours of Friday 23 September, when reporting results for 143 of Zambia’s 150 we know the results of the presiden- constituencies, the Electoral Commission of Zambia announced that Sata had taken 43 per- tial election, remember that we won’t cent of the votes against President Banda’s 36 percent. The number of voters in the remaining know the full results of neither the 7 constituencies was smaller than the more than 188,000 votes separating the two rivals. parliamentary nor the local govern- ment elections any time soon, as several “I therefore declare Michael Chilufya Sata to be duly elected as President of the Republic of of these have been postponed. -

Zambia Country R

The South African Institute of International Affairs ft L — W M* Strengthening parliamentary democracy in SADC countries Zambia country r Bizeck Phiri Series editor: Tim Hughes THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Strengthening parliamentary democracy in SADC countries Zambia country report Bizeck Phiri SERIES EDITOR: TIM HUCHES The South African Institute of International Affairs' Strengthening parliamentary democraq' in SADC countries project is made possible through the generous financial support of the Royal Danish Embassy, Pretoria. Copyright ©SANA, 2005 All rights reserved THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ISBN: 1-919969-07-1 Strengthening parliamentary democracy in SADC countries Zambia country report Please note that all amounts are in US$, unless otherwise indicated. SANA National Office Bearers Fred Phaswana Elisabeth Bradley • Moeletsi Mbeki Brian Hawksworth • Alec Pienaar Dr Greg Mills Acknowledgements I wish to express my sincere gratitude to members of parliament (MPs), members of civil society organisations (CSOs) and individuals who agreed to be interviewed by my research assistants. I also wish to thank the staff of the parliament of Zambia, especially the Office of the Clerk for allowing Chikomeni Banda to respond to the paper when it was presented at the Lusaka seminar/workshop on Strengthening Parliamentary Democracy on 16 December 2004. I wish to acknowledge the role played by my research assistants and their professional conduct while in the field. My gratitude also goes to CHN Haantobolo for his assistance during the seminar/workshop as well as delivering invitation letters to MPs and CSOs. I am equally grateful to Michael Mwewa, an undergraduate student of Mass Communication, for his role in inviting members of the media to cover the seminar/workshop.