Late Talkers: Do Good Predictors Oy Outcome Exist?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autism Spectrum Disorder: an Overview and Update

Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Overview and Update Brandon Rennie, PhD Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities Division Center for Development and Disability University of New Mexico Department of Pediatrics DATE, 2016 Acknowledgements: Courtney Burnette, PHD, Sylvia Acosta, PhD, Maryann Trott, MA, BCBA Introduction to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) • What is ASD? • A complex neurodevelopmental condition • Neurologically based- underlying genetic and neurobiological origins • Developmental- evident early in life and impacts social development • Lifelong- no known cure • Core characteristics • Impairments in social interaction and social communication • Presence of restricted behavior, interests and activities • Wide variations in presentation DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria • Deficits in social communication and social interaction (3) • Social approach/interaction • Nonverbal communication • Relationships • Presence of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (2) • Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, objects, speech • Routines • Restricted interests • Sensory* From Rain Man To Sheldon Cooper- Autism in the Media 1910 Bleuler • First use of the word autistic • From “autos”, Greek word meaning “self” 1943 Leo Kanner 1944 Hans Asperger 1975 1:5000 1985 1:2500 1995 1:500 “When my brother trained at Children's Hospital at Harvard in the 1970s, they admitted a child with autism, and the head of the hospital brought all of the residents through to see. He said, 'You've got to see this case; you'll never see it -

Autism Terminology Guidelines

The language we use to talk about autism is important. A paper published in our journal (Kenny, Hattersley, Molins, Buckley, Povey & Pellicano, 2016) reported the results of a survey of UK stakeholders connected to autism, to enquire about preferences regarding the use of language. Based on the survey results, we have created guidelines on terms which are most acceptable to stakeholders in writing about autism. Whilst these guidelines are flexible, we would like researchers to be sensitive to the preferences expressed to us by the UK autism community. Preferred language The survey highlighted that there is no one preferred way to talk about autism, and researchers must be sensitive to the differing perspectives on this issue. Amongst autistic adults, the term ‘autistic person/people’ was the most commonly preferred term. The most preferred term amongst all stakeholders, on average, was ‘people on the autism spectrum’. Non-preferred language: 1. Suffers from OR is a victim of autism. Consider using the following terms instead: o is autistic o is on the autism spectrum o has autism / an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) / an autism spectrum condition (ASC) (Note: The term ASD is used by many people but some prefer the term 'autism spectrum condition' or 'on the autism spectrum' because it avoids the negative connotations of 'disability' or 'disorder'.) 2. Kanner’s autism 3. Referring to autism as a disease / illness. Consider using the following instead: o autism is a disability o autism is a condition 4. Retarded / mentally handicapped / backward. These terms are considered derogatory and offensive by members of the autism community and we would advise that they not be used. -

Young Adults and Transitioning Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder

2017 REPORT TO CONGRESS Young Adults and Transitioning Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder Prepared by the: Department of Health and Human Services Submitted by the: National Autism Coordinator U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Cover Design Medical Arts Branch, Office of Research Services, National Institutes of Health Copyright Information All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied. A suggested citation follows. Suggested Citation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Report to Congress: Young Adults and Transitioning Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. October 2017. Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2017AutismReport.pdf Young Adults and Transitioning Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder The Autism Collaboration, Accountability, Research, Education and Support Act (Autism CARES Act) of 2014 REPORT TO CONGRESS Submitted by the National Autism Coordinator of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services August 3, 2017 Table of Contents Interagency Workgroup on Young Adults and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder Transitioning to Adulthood ................................................................................................ iv Steering Committee .................................................................................................... iv Members .................................................................................................................. iv OASH Stakeholder -

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Fact Sheet

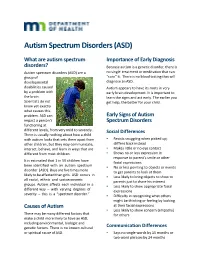

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) What are autism spectrum Importance of Early Diagnosis disorders? Because autism is a genetic disorder, there is Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a no single treatment or medication that can group of “cure” it. There is no blood testing that will developmental diagnose an ASD. disabilities caused Autism appears to have its roots in very by a problem with early brain development. It is important to the brain. learn the signs and act early. The earlier you Scientists do not get help, the better for your child. know yet exactly what causes this problem. ASD can Early Signs of Autism impact a person’s Spectrum Disorders functioning at different levels, from very mild to severely. Social Differences There is usually nothing about how a child with autism looks that sets them apart from ▪ Resists snuggling when picked up; other children, but they may communicate, stiffens back instead interact, behave, and learn in ways that are ▪ Makes little or no eye contact different from most children. ▪ Shows no or less expression in response to parent’s smile or other It is estimated that 1 in 59 children have facial expressions been identified with an autism spectrum ▪ No or less pointing to objects or events disorder (ASD). Boys are five times more to get parents to look at them likely to be affected than girls. ASD occurs in ▪ Less likely to bring objects to show to all racial, ethnic and socioeconomic parents just to share his interest groups. Autism affects each individual in a ▪ Less likely to show appropriate facial different way – with varying degrees of expressions severity – this is a “spectrum disorder.” ▪ Difficulty in recognizing what others might be thinking or feeling by looking Causes of Autism at their facial expressions ▪ Less likely to show concern (empathy) There may be many different factors that for others make a child more likely to have an ASD, including environmental, biologic and genetic factors. -

Fragile X Syndrome

European Journal of Human Genetics (2008) 16, 666–672 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1018-4813/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/ejhg PRACTICAL GENETICS In association with Fragile X syndrome Fragile X syndrome, an X-linked dominant disorder with reduced penetrance, is associated with intellectual and emotional disabilities ranging from learning problems to mental retardation, and mood instability to autism. It is most often caused by the transcriptional silencing of the FMR1 gene, due to an expansion of a CGG repeat found in the 50-untranslated region. The FMR1 gene product, FMRP, is a selective RNA-binding protein that negatively regulates local protein synthesis in neuronal dendrites. In its absence, the transcripts normally regulated by FMRP are over translated. The resulting over abundance of certain proteins results in reduced synaptic strength due to AMPA receptor trafficking abnormalities that lead, at least in part, to the fragile X phenotype. In brief Genetic testing for this repeat expansion is diagnostic for this syndrome, and testing is appropriate in all Fragile X syndrome is a common inherited form of children with developmental delay, mental retardation mental retardation that can be associated with features or autism. of autism. Fragile X syndrome is inherited from individuals, The physical features of fragile X syndrome are subtle usually females, who typically carry an unstable and may not be obvious. premutation allele of the CGG-repeat tract in The vast majority of cases of fragile X syndrome are FMR1. caused by the expansion to over 200 copies of a CGG Premutation carriers are themselves at risk of prema- repeat in the 50-untranslated region of FMR1 that shuts ture ovarian failure and the fragile X-associated tremor/ off transcription of the gene. -

Autism Spectrum Disorder 299.00 (F84.0)

Autism Spectrum Disorder 299.00 (F84.0) Diagnostic Criteria according to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual V A. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive, see text): 1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions. 2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication. 3. Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers. Specify current severity – Social Communication: Level 1 – Requiring Support 2- Substantial Support 3-Very Substantial Support Please refer to attached table for definition of levels. B. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive; see text): 1. Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypies, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases). 2. Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns or verbal nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat food every day). -

Lexical Composition in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Leslie Rescorla Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Psychology Faculty Research and Scholarship Psychology 2013 Lexical Composition in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Leslie Rescorla Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Paige Safyer Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/psych_pubs Part of the Child Psychology Commons Custom Citation Rescorla, Leslie A., and Paige Safyer. "Lexical Composition in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)." Journal of Child Language 40, no. 1 (2013): 47-68, doi: 110.1017/S0305000912000232. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/psych_pubs/10 For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Child Lang. 40 (2013), 47–68. f Cambridge University Press 2012 doi:10.1017/S0305000912000232 Lexical composition in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)* LESLIE RESCORLA AND PAIGE SAFYER Psychology, Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania, USA (Received 19 September 2011 – Revised 23 December 2011 – Accepted 17 May 2012) ABSTRACT For sixty-seven children with ASD (age 1;6 to 5;11), mean Total Vocabulary score on the Language Development Survey (LDS) was 65.3 words; twenty-two children had no reported words; and twenty-one children had 1–49 words. When matched for vocabulary size, children with ASD and children in the LDS normative sample did not differ in semantic category or word-class scores. Q correlations were large when percentage use scores for the ASD sample were compared with those for samples of typically developing children as well as children with vocabularies <50 words. -

Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder

ARTÍCULO DE REVISIÓN Deterioro Cognitivo y Demencias en Adultos con Trastorno del Espectro Autista Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder David Toloza Ramírez,1,2 Carolina Iturra Pedreros,3,4 Grisol Iturra Pedreros3,4 Resumen El Trastorno del Espectro Autista (TEA) clásicamente ha sido estudiado en población infantil, no obstante, en la actualidad 1/68 adultos vive con este trastorno del neurodesarrollo. Las personas con TEA en edad adulta manifiestan síntomas sugerentes de deterioro cognitivo, los cuales comprometen rápidamente diversas funciones cognitivas. El deterioro cognitivo y las altera- ciones conductuales favorecen- en personas con TEA- el desarrollo de procesos neurodegenerativos como la demencia Fronto- temporal (DFT) y la demencia tipo Alzheimer (EA), lo cual afecta las actividades de la vida diaria (AVD). El objetivo de esta revisión es investigar la progresión del TEA hacia estados de deterioro cognitivo y cuadros demenciales en edad adulta. Nuestra metodología incluyó análisis cualitativos de investigaciones realizadas desde el año 2000 al 2020 exclusivamente en idioma in- glés. Los resultados demuestran que los adultos con TEA desarrollan deterioro cognitivo y demencias precozmente en relación a la población general, afectando principalmente importantes funciones cognitivas como la memoria y la función ejecutiva. En conclusión, la discapacidad intelectual de grado moderado a profundo, así como las reducciones en la sustancia blanca del ce- rebro, parecen ser uno de los precursores para el desarrollo de deterioro cognitivo y procesos demenciales en adultos con TEA. Palabras clave: Trastorno del Espectro Autista, Adultez, Discapacidad Intelectual, Deterioro Cognitivo, Demencias. Abstract Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has been studied mainly in children. -

The Fragile X Syndrome–Autism Comorbidity: What Do We Really Know?

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 16 October 2014 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00355 The fragile X syndrome–autism comorbidity: what do we really know? Leonard Abbeduto 1,2*, Andrea McDuffie 1,2 and Angela John Thurman 1,2 1 MIND Institute, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA, USA 2 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA, USA Edited by: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a common comorbid condition in people with fragile Anne C. Wheeler, Carolina Institute X syndrome (FXS). It has been assumed that ASD symptoms reflect the same underlying for Developmental Disabilities; University of North Carolina at psychological and neurobiological impairments in both FXS and non-syndromic ASD, which Chapel Hill, USA has led to the claim that targeted pharmaceutical treatments that are efficacious for core Reviewed by: symptoms of FXS are likely to be beneficial for non-syndromic ASD as well. In contrast, we Molly Losh, Northwestern present evidence from a variety of sources suggesting that there are important differences University, USA in ASD symptoms, behavioral and psychiatric correlates, and developmental trajectories Dejan Budimirovic, Kennedy Krieger Institute/The Johns Hopkins between individuals with comorbid FXS and ASD and those with non-syndromic ASD. We University, USA also present evidence suggesting that social impairments may not distinguish individuals *Correspondence: with FXS with and without ASD. Finally, we present data that demonstrate that the Leonard Abbeduto, MIND Institute, neurobiological substrates of the behavioral impairments, including those reflecting core University of California, Davis, 2825 ASD symptoms, are different in FXS and non-syndromic ASD. Together, these data suggest 50th Street, Sacramento, CA 95817, USA that there are clinically important differences between FXS and non-syndromic ASD e-mail: leonard.abbeduto@ucdmc. -

Best Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorders 2009

Best Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorders 2009 State of Vermont Agency of Human Services Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living Division of Disability and Aging Services 103 South Main Street Waterbury, VT 05671-1601 http://www.dail.vermont.gov Telephone: (802) 241-2614 TTY: (802) 241-3557 Fax: (802) 241-4224 Primary Writer and Researcher: Clare McFadden, M.Ed., Autism Specialist, Vermont Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living Committee Members Kim Aakre, MD, Gail Falk, President of the American Academy of Pediatrics – Director, Office of Public Guardian VT Chapter Vermont Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living Carol Andrew, EdD, OTR, Claudia Gibson, MD, FITP Autism Consultant, Assistant Professor of Child Neurologist, Deer Creek Psychological Pediatrics, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center Associates Claire Bruno, M.Ed., Carol Hassler, MD, Autism Consultant, Department of Education FAAP, Medical Director, Children with Special Health Needs, Neurodevelopmental Pediatrician, Director, Child Development Clinic, VT Department of Health, MCH Division Marc Carpenter, MA, Dean J.M. Mooney, Ph.D., Licensed Psychologist-Master, NCSP, Maple Leaf Clinic Community Access Program of Rutland County Leslie Conroy, MD, Patricia A. Prelock, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, Otter Creek Dean, College of Nursing & Health Sciences, Associates Professor, Communication Sciences, University of Vermont Stephen Contompasis, MD, Linda Veith Rosenblad, Ph.D, -

A Symptom-Based Approach to Treatment of Psychosis in Autism Spectrum Disorder* Victoria Bell†, Henry Dunne†, Tharun Zacharia, Katrina Brooker and Sukhi Shergill

BJPsych Open (2018) 4, 1–4. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2017.2 Short report A symptom-based approach to treatment of psychosis in autism spectrum disorder* Victoria Bell†, Henry Dunne†, Tharun Zacharia, Katrina Brooker and Sukhi Shergill Summary The optimal management of autism with psychosis remains Copyright and usage unclear. This report describes a 22-year-old man with autism and © The Royal College of Psychiatrists 2018. This is an Open Access psychosis who was referred to a tertiary-level specialist psych- article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons osis service, following a 6-year history of deterioration in mental Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivatives licence (http://crea- health starting around the time of sitting GCSE examinations and tivecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non- an episode of bullying at school. We describe the individualised commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any symptom-based approach that was effective in his treatment. medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press Declaration of interest must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a The authors declare no conflict of interest. derivative work. Knowledge of both autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and psychosis and investigate the co-occurrence of symptoms.9 The focus on clari- has developed within spectrum constructs. Despite the long history fying the diagnosis may be based on clinician preference or a way of of association between these disorders, there is often little clinician managing complexity, yet this may prove to be an obstacle in the awareness of how to assess and treat psychosis when it coexists with advancement of the formulation and treatment of the difficult ASD. -

High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder And

Chaste et al. Molecular Autism 2012, 3:5 http://www.molecularautism.com/content/3/1/5 RESEARCH Open Access High-functioning autism spectrum disorder and fragile X syndrome: report of two affected sisters Pauline Chaste1,2,3, Catalina Betancur4,5,6, Marion Gérard-Blanluet7, Anne Bargiacchi3, Suzanne Kuzbari7, Séverine Drunat7, Marion Leboyer2,8,9, Thomas Bourgeron1,10,11 and Richard Delorme1,2,3,10* Abstract Background: Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability (ID), as well as the most frequent monogenic cause of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Men with FXS exhibit ID, often associated with autistics features, whereas women heterozygous for the full mutation are typically less severely affected; about half have a normal or borderline intelligence quotient (IQ). Previous findings have shown a strong association between ID and ASD in both men and women with FXS. We describe here the case of two sisters with ASD and FXS but without ID. One of the sisters presented with high-functioning autism, the other one with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified and low normal IQ. Methods: The methylation status of the mutated FMR1 alleles was examined by Southern blot and methylation- sensitive polymerase chain reaction. The X-chromosome inactivation was determined by analyzing the methylation status of the androgen receptor at Xq12. Results: Both sisters carried a full mutation in the FMR1 gene, with complete methylation and random X chromosome inactivation. We present the phenotype of the two sisters and other family members. Conclusions: These findings suggest that autistic behaviors and cognitive impairment can manifest as independent traits in FXS.