History of Pseudoscience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Science (HIST SCI) 1

History of Science (HIST SCI) 1 HIST SCI 133 — BIOLOGY AND SOCIETY, 1950 - TODAY HISTORY OF SCIENCE (HIST 3 credits. From medical advancements to environmental crises and global food SCI) shortages, the life sciences are implicated in some of the most pressing social issues of our time. This course explores events in the history of biology from the mid-twentieth century to today, and examines how HIST SCI/ENVIR ST/HISTORY 125 — GREEN SCREEN: ENVIRONMENTAL developments in this science have shaped and are shaped by society. In PERSPECTIVES THROUGH FILM the first unit, we investigate the origins of the institutions, technologies, 3 credits. and styles of practice that characterize contemporary biology, such From Teddy Roosevelt's 1909 African safari to the Hollywood blockbuster as the use of mice as "model organisms" for understanding human King Kong, from the world of Walt Disney to The March of the Penguins, diseases. The second unit examines biological controversies such as the cinema has been a powerful force in shaping public and scientific introduction of genetically modified plants into the food supply. The final understanding of nature throughout the twentieth and twenty-first unit asks how biological facts and theories have been and continue to be century. How can film shed light on changing environmental ideas and used as a source for understanding ourselves. Enroll Info: None beliefs in American thought, politics, and culture? And how can we come Requisites: None to see and appreciate contested issues of race, class, and gender in Course Designation: Breadth - Either Humanities or Social Science nature on screen? This course will explore such questions as we come Level - Elementary to understand the role of film in helping to define the contours of past, L&S Credit - Counts as Liberal Arts and Science credit in L&S present, and future environmental visions in the United States, and their Repeatable for Credit: No impact on the real world struggles of people and wildlife throughout the Last Taught: Spring 2021 world. -

![Arxiv:2102.03380V2 [Cs.AI] 29 Jun 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5045/arxiv-2102-03380v2-cs-ai-29-jun-2021-65045.webp)

Arxiv:2102.03380V2 [Cs.AI] 29 Jun 2021

Reproducibility in Evolutionary Computation MANUEL LÓPEZ-IBÁÑEZ, University of Málaga, Spain JUERGEN BRANKE, University of Warwick, UK LUÍS PAQUETE, University of Coimbra, CISUC, Department of Informatics Engineering, Portugal Experimental studies are prevalent in Evolutionary Computation (EC), and concerns about the reproducibility and replicability of such studies have increased in recent times, reflecting similar concerns in other scientific fields. In this article, we discuss, within the context of EC, the different types of reproducibility and suggest a classification that refines the badge system of the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) adopted by ACM Transactions on Evolutionary Learning and Optimization (https://dlnext.acm.org/journal/telo). We identify cultural and technical obstacles to reproducibility in the EC field. Finally, we provide guidelines and suggest tools that may help to overcome some of these reproducibility obstacles. Additional Key Words and Phrases: Evolutionary Computation, Reproducibility, Empirical study, Benchmarking 1 INTRODUCTION As in many other fields of Computer Science, most of the published research in Evolutionary Computation (EC) relies on experiments to justify their conclusions. The ability of reaching similar conclusions by repeating an experiment performed by other researchers is the only way a research community can reach a consensus on an empirical claim until a mathematical proof is discovered. From an engineering perspective, the assumption that experimental findings hold under similar conditions is essential for making sound decisions and predicting their outcomes when tackling a real-world problem. The “reproducibility crisis” refers to the realisation that many experimental findings described in peer-reviewed scientific publications cannot be reproduced, because e.g. they lack the necessary data, they lack enough details to repeat the experiment or repeating the experiment leads to different conclusions. -

Urban Myths Mythical Cryptids

Ziptales Advanced Library Worksheet 2 Urban Myths Mythical Cryptids ‘What is a myth? It is a story that pretends to be real, but is in fact unbelievable. Like many urban myths it has been passed around (usually by word of mouth), acquiring variations and embellishments as it goes. It is a close cousin of the tall tale. There are mythical stories about almost any aspect of life’. What do we get when urban myths meet the animal kingdom? We find a branch of pseudoscience called cryptozoology. Cryptozoology refers to the study of and search for creatures whose existence has not been proven. These creatures (or crytpids as they are known) appear in myths and legends or alleged sightings. Some examples include: sea serpents, phantom cats, unicorns, bunyips, giant anacondas, yowies and thunderbirds. Some have even been given actual names you may have heard of – do Yeti, Owlman, Mothman, Cyclops, Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster sound familiar? Task 1: Choose one of the cryptids from the list above (or perhaps one that you may already know of) and write an informative text identifying the following aspects of this mythical creature: ◊ Description ◊ Features ◊ Location ◊ First Sighting ◊ Subsequent Sightings ◊ Interesting Facts (e.g. how is it used in popular culture? Has it been featured in written or visual texts?) Task 2: Cryptozoologists claim there have been cases where species now accepted by the scientific community were initially considered urban myths. Can you locate any examples of creatures whose existence has now been proven but formerly thought to be cryptids? Extension Activities: • Cryptozoology is called a ‘pseudoscience’ because it relies solely on anecdotes and reported sightings rather than actual evidence. -

Some Observations on Avoiding Pitfalls in Developing Future Flight Systems

AIAA 97-3209 Some Observations on Avoiding Pitfalls in Developing Future Flight Systems Gary L. Bennett Metaspace Enterprises Emmett, Idaho; U.S.A. 33rd AIAA/ASME/SAEIASEEJoint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit July 6 - 9, 1997 I Seattle, WA For permission to copy or republish, contact the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1801 Alexander Bell Drive, Suite 500, Reston, VA 22091 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON AVOIDING PITFALLS IN DEVELOPING FUTURE FLIGHT SYSTEMS Gary L. Bennett* 5000 Butte Road Emmett, Idaho 83617-9500 Abstract Given the speculative proposals and the interest in A number of programs and concepts have been developing breakthrough propulsion systems it seems proposed 10 achieve breakthrough propulsion. As an prudent and appropriate to review some of the pitfalls cautionary aid 10 researchers in breakthrough that have befallen other programs in "speculative propulsion or other fields of advanced endeavor, case science" so that similar pitfalls can be avoided in the histories of potential pitfalls in scientific research are future. And, given the interest in UFO propulsion, described. From these case histories some general some guidelines to use in assessing the reality of UFOs characteristics of erroneous science are presented. will also be presented. Guidelines for assessing exotic propulsion systems are suggested. The scientific method is discussed and some This paper will summarize some of the principal tools for skeptical thinking are presented. Lessons areas of "speculative science" in which researchers learned from a recent case of erroneous science are were led astray and it will then provide an overview of listed. guidelines which, if implemented, can greatly reduce Introduction the occurrence of errors in research. -

The Historical Turn in the Philosophy of Science

THE HISTORICAL TURN IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE 1 Developments in the History of Science The history of science has a long history. Aristotle’s scientific works are prefaced by historical account of those sciences, and this model persisted through medieval times until and including the rise of modern science in the era of the scientific revolution. Joseph Priestley, for example, entitled two of his books of pioneering research The History and Present State of Electricity and The History and Present State of Discov- eries Relating to Vision, Light, and Colours. For many such early modern authors the history of science serves as a propaedeutic. William Whewell’s A History of the Induc- tive Sciences (1857) is regarded as the first genuinely modern work of the history of science. Even so, Whewell’s scholarship has an extra-historical purpose, which was to furnish the materials against which a satisfactory philosophy of science could be con- structed. While Whewell rejected a Leibnizian logic of discovery, he did nonetheless believe that general principles of scientific inference could be uncovered by careful consideration of the history of scientific research. Whewell’s approach was followed by several early positivists, notably, Mach, Ostwald, and Duhem. Nonetheless, as positivism developed philosophically it also became more ahis- torical. Carnap’s programme of a priori inductive logic was premised on a distinction between a context of discovery and a context of justification. The former concerned the process of coming up with an hypothesis, whereas the latter concerns its justification relative to the evidence. The former would be the province of psychology, although it may depend so much on details of individual biography that few general principles may be derived even a posteriori. -

ANG 5012, Section 6423 Spring 2017 FANTASTIC ANTHROPOLOGY and FRINGE SCIENCE

ANG 5012, section 6423 Spring 2017 FANTASTIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND FRINGE SCIENCE Time: Mondays, periods 7-9 (1:55 – 4:55) Place: TUR 2303 Instructor: David Daegling, Turlington B376 352-294-7603 [email protected] Office Hours: M 10:30 – 11:30 AM; W 1:00 – 3:00 PM. COURSE OBJECTIVES: This course examines the articulation and perpetuation of so-called paranormal and fringe scientific theories concerning the human condition. We will examine these unconventional claims with respect to 1) underlying belief systems, 2) empirical and logical foundations, 3) persistence in the face of refutation, 4) popular treatment by mass media and 5) institutional reaction. The course is divided into five parts. Part I explores forms of inquiry and considers the demarcation of science from pseudoscience. Part II concerns unconventional theories of human evolution. Part III investigates unorthodox ideas of human biology. Part IV examines claims of extraterrestrial and supernatural contact in the world today. Part V further scrutinizes institutional reaction to fringe science, popular coverage of science, and the culture of science in the contemporary United States. COURSE REQUIREMENTS: Attendance is mandatory. Unexcused absences (i.e., other than medical or family emergency) result in a half grade reduction of your final grade. Participation in group and class discussions is required (50% of your final grade). In addition, written work is required for each of the five parts of the course (50% of your grade). These will take the form of essays and short papers to be completed concurrently with our discussions of these topics. Late papers are subject to a full letter grade reduction. -

Mapping the Creation-Evolution Debate in Public Life

MAPPING THE CREATION-EVOLUTION DEBATE IN PUBLIC LIFE by ANDREW JUDSON HART (Under the Direction of Edward Panetta) ABSTRACT Evolution versus creation is a divisive issue as religion is pitted against science in public discourse. Despite mounting scientific evidence in favor of evolution and legal decisions against the teaching of creationism in public schools, the number of advocates who still argue for creationist teaching in the science curriculum of public schools remains quite large. Public debates have played a key role in the creationist movement, and this study examines public debates between creationists and evolutionists over thirty years to track trends and analyze differences in arguments and political style in an attempt to better understand why creationism remains salient with many in the American public. INDEX WORDS: Creation; Evolution; Public Debate; Argumentation; Political Style; Bill Nye MAPPING THE CREATION-EVOLUTION DEBATE IN PUBLIC LIFE by ANDREW JUDSON HART B.A., The University of Georgia, 2010 B.S.F.R., The University of Georgia, 2010 M.A.T., The University of Georgia, 2014 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Andrew Judson Hart All Rights Reserved MAPPING THE CREATION-EVOLUTION DEBATE IN PUBLIC LIFE by ANDREW JUDSON HART Major Professor: Edward Panetta Committee: Barbara Biesecker Thomas Lessl Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without Dr. Ed Panetta pushing me down the path to study the creation-evolution debates and his work with me on this through the many drafts and edits. -

163 Marco Ciardi As a Real Science Fiction Novel, This Essay

book reviews 163 Marco Ciardi Il mistero degli antichi astronauti. Rome: Carocci, 2017, 220 pages, isbn: 978-88-43-08546-0. As a real science fiction novel, this essay begins with a classical “what if?” sce- nario: what if Earth was invaded by a civilization with an advanced knowledge and technology in ancient times? The “theory of the ancient astronauts” was exactly this: the possibility that extraterrestrial entities reached our planet in the past and left evidence of their stay, such as archaeological finds of their coherent historical context or even genetic manipulations of the prehistoric hominids, therefore constituting a direct influence on human evolution. The literature on this topic has been flourishing since the xix century, but the issue is not only a historical one. What about the scientific basis of this “theory”? The answer to this question is actually an enigma: Marco Ciardi tries to solve the puzzle in his book, piecing together the origins of this theme. Ciardi uses scientific and pseudo-scientific books as means to investigate the precincts in which the problem has been addressed, showing how “the theory of the ancient astronauts” has influenced popular texts such as science fiction novels, short stories and comics. The book is structured in three parts: “The context of the mystery”, “The definition of the mystery” and “The diffusion of the mystery”: a chronological as well as logical division that explains when the problem was born, how it consolidated and became a popular subject. In the first part of the book, the author shows how men believed that uni- verse was populated by different creatures since ancient times, while only in the last two centuries this belief became a pre-eminent topic in literature. -

History of Science and History of Technology (Class Q, R, S, T, and Applicable Z)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COLLECTIONS POLICY STATEMENTS History of Science and History of Technology (Class Q, R, S, T, and applicable Z) Contents I. Scope II. Research strengths III. General collecting policy IV. Best editions and preferred formats V. Acquisitions sources: current and future VI. Collecting levels I. Scope This Collections Policy Statement covers all of the subclasses of Science and Technology and treats the history of these disciplines together. In a certain sense, most of the materials in Q, R, S, and T are part of the history of science and technology. The Library has extensive resources in the history of medicine and agriculture, but many years ago a decision was made that the Library should not intensively collect materials in clinical medicine and technical agriculture, as they are subject specialties of the National Library of Medicine and the National Agricultural Library, respectively. In addition, some of the numerous abstracting and indexing services, catalogs of other scientific and technical collections and libraries, specialized bibliographies, and finding aids for the history of science and technology are maintained in class Z. See the list of finding aids online: http://findingaids.loc.gov/. II. Research strengths 1. General The Library’s collections are robust in both the history of science and the history of technology. Both collections comprise two major elements: the seminal works of science and technology themselves, and historiographies on notable scientific and technological works. The former comprise the original classic works of science and technology as they were composed by the men and women who ushered in the era of modern science and invention. -

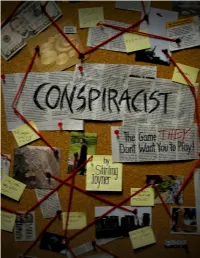

Reptilians Are a Race of Lizard People of Unknown Origin

[title page, cover goes here] CREDITS Special thanks to Brian Williamson for being a great conversation partner and friend. Without you, this game would not be nearly as good. Concept, Design, and Writing: Stirling Joyner Editing: Caroline Harbour and Morgan Rawlinson Layout: John Fischer Aesthetic Advice: Morgan Rawlinson Cover Art: Stirling Joyner & Morgan Rawlinson Playtesting: Josie Joyner, Darcy Joyner, Brian Williamson, Garrett Gaunch, Elizabeth Williamson, Jeff Seitz, Dan Schaeffer Third-Party Images Used in Cover: Public Domain: Five dollar bill, Crop circles (Jabberocky), UFO CC BY-SA 3.0: Lizard (Ksenija Putilin) Fair Use: Newspaper clippings (Chicago Tribune), Warning lable, Reptilian secret service agent (YouTuber Reptillian Resistance), Google Earth image of Area 51 (DigitalGlobe, Google) CC BY 4.0: CC BY-SA button License: This roleplaying game and its cover art are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Under this license, you are free to copy, share, and remix all the content in this book for any purpose, even commercially. Under the following conditions: 1. You attribute Stirling Joyner. 2. You license any derivative works under the same license. Support Me: I released this game for free. If you like it and want to help me make more, please become a supporter on Patreon or send me a donation on PayPal. You can also pay what you want for this game on DriveThruRPG. • Patreon Link: patreon.com/sjrpgdesign • PayPal Link: paypal.me/sjrpgdesign • DriveThruRPG Link: drivethrurpg.com/browse.php?keywords=stirling+joyner Thank you Dan Shauer (DrLeaf), Johnathan & Jenn Madera, Austin Farrow, and Keller Scholl for supporting me on Patreon already! 1 I stumbled out of the crashed alien spacecraft and toward the secret government bunker that housed the real Statue of Liberty. -

Evidence-Based Alternative Medicine?

(YLGHQFH%DVHG$OWHUQDWLYH0HGLFLQH" .LUVWLQ%RUJHUVRQ 3HUVSHFWLYHVLQ%LRORJ\DQG0HGLFLQH9ROXPH1XPEHU$XWXPQ SS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2,SEP )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by Dalhousie University (13 Jul 2016 15:54 GMT) 05/Borgerson/Final/502–15 9/6/05 6:55 PM Page 502 Evidence-Based Alternative Medicine? Kirstin Borgerson ABSTRACT The validity of evidence-based medicine (EBM) is the subject of on- going controversy.The EBM movement has proposed a “hierarchy of evidence,” ac- cording to which randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses of RCTs provide the most reliable evidence concerning the efficacy of medical interventions. The evaluation of alternative medicine therapies highlights problems with the EBM hierarchy. Alternative medical researchers—like those in mainstream medicine—wish to evaluate their therapies using methods that are rigorous and that are consistent with their philosophies of medicine and healing.These investigators have three ways to relate their work to EBM.They can accept the EBM hierarchy and carry out RCTs when possible; they can accept the EBM standards but argue that the special characteristics of alternative medicine warrant the acceptance of “lower” forms of evidence; or they can challenge the EBM approach and work to develop new research designs and new stan- dards of evidence that reflect their approach to medical care. For several reasons, this last option is preferable. First, it will best meet the needs of alternative medicine prac- titioners. Moreover, because similar problems beset the evaluation of mainstream med- ical therapies, reevaluation of standards of evidence will benefit everyone in the med- ical community—including, most importantly, patients. -

Creation/Evolution

Creation/Evolution Are the fossils in the wrong order for human evolution? Issue VIII CONTENTS Spring 1982 ARTICLES 1 Charles Darwin: A Centennial Tribute by H. lames Birx 11 Kelvin Was Not a Creationist by Stephen G Brush 14 Are There Human Fossils in the "Wrong Place" for Evolution by Ernest C. Conrad 23 Answers to Creationist Attacks on Carbon-14 Dating by Christopher Gregory Weber REPORTS .30 Creation-Evoiution Debates: Who's Winning Them Now? by Frederick Edwards 43 News Briefs LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED FORTHCOMING PROGRAMS PBS TV Program, "Creation vs. Evolution: Battle in the Classroom," airing Wednesday, July 7, at 9:00 PM Eastern time. This sixty-minute documentary ex- plores the growing war of litigation over creationism in the public schools with interviews of teachers, scientists, religious, and political leaders, students, and parents in the forefront of the battle. The program particularly examines the "two-model" approach used recently in Livermore, California, and gets the reac- tions of the principal individuals involved. The basic ideas of creationism and evolution are argued in a "point-counterpoint" segment between Duane Gish and Russell Doolittle. The age of the earth and universe are covered. Other per- sonalities featured include: Tim LaHaye; James Robison; Richard Bliss; Nell, Kelly, and Casey Segraves; John N. Moore; Bill Keith; and even Ronald Reagan. A featured representative on the evolution side is William V. Mayer. The docu- mentary is a production of KPBS, San Diego. 1982 Annual Fellows' Meeting at Guilford College, August 8-13, Greensboro, North Carolina. Of the sixteen programs, one is entitled "Religion and Science: The Creationist Debate." Contact John O.