The Mechanics of Large Volcanic Eruptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety

Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety Edited by Thomas J. Casadevall U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2047 Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety held in Seattle, Washington, in July I991 @mposium sponsored by Air Line Pilots Association Air Transport Association of America Federal Aviation Administmtion National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Geological Survey amposium co-sponsored by Aerospace Industries Association of America American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Flight Safety Foundation International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior National Transportation Safety Board UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety (1st : 1991 Seattle, Wash.) Volcanic ash and aviation safety : proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety I edited by Thomas J. Casadevall ; symposium sponsored by Air Line Pilots Association ... [et al.], co-sponsored by Aerospace Indus- tries Association of America ... [et al.]. p. cm.--(US. Geological Survey bulletin ; 2047) "Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety held in Seattle, Washington, in July 1991." Includes bibliographical references. -

Geology and Mineralization of the Sierra Blanca Peaks, Hudspeth County, Texas W

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/31 Geology and mineralization of the Sierra Blanca Peaks, Hudspeth County, Texas W. N. McAnulty, 1980, pp. 263-266 in: Trans Pecos Region (West Texas), Dickerson, P. W.; Hoffer, J. M.; Callender, J. F.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 31st Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 308 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1980 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

(2000), Voluminous Lava-Like Precursor to a Major Ash-Flow

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 98 (2000) 153–171 www.elsevier.nl/locate/jvolgeores Voluminous lava-like precursor to a major ash-flow tuff: low-column pyroclastic eruption of the Pagosa Peak Dacite, San Juan volcanic field, Colorado O. Bachmanna,*, M.A. Dungana, P.W. Lipmanb aSection des Sciences de la Terre de l’Universite´ de Gene`ve, 13, Rue des Maraıˆchers, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland bUS Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Rd, Menlo Park, CA, USA Received 26 May 1999; received in revised form 8 November 1999; accepted 8 November 1999 Abstract The Pagosa Peak Dacite is an unusual pyroclastic deposit that immediately predated eruption of the enormous Fish Canyon Tuff (ϳ5000 km3) from the La Garita caldera at 28 Ma. The Pagosa Peak Dacite is thick (to 1 km), voluminous (Ͼ200 km3), and has a high aspect ratio (1:50) similar to those of silicic lava flows. It contains a high proportion (40–60%) of juvenile clasts (to 3–4 m) emplaced as viscous magma that was less vesiculated than typical pumice. Accidental lithic fragments are absent above the basal 5–10% of the unit. Thick densely welded proximal deposits flowed rheomorphically due to gravitational spreading, despite the very high viscosity of the crystal-rich magma, resulting in a macroscopic appearance similar to flow- layered silicic lava. Although it is a separate depositional unit, the Pagosa Peak Dacite is indistinguishable from the overlying Fish Canyon Tuff in bulk-rock chemistry, phenocryst compositions, and 40Ar/39Ar age. The unusual characteristics of this deposit are interpreted as consequences of eruption by low-column pyroclastic fountaining and lateral transport as dense, poorly inflated pyroclastic flows. -

Volcanic Eruption Impacts Student Worksheet

Volcanic Eruption Impacts Student Worksheet Explosive and Effusive Volcanoes The type of volcanic eruption is largely determined by magma composition. Flux-mediated melting at subduction zones creates a felsic magma with high levels of carbon dioxide and water. These dissolved gases explode during eruption. Effusive volcanoes have a hotter, more mafic magma with lower levels of dissolved gas, allowing them to erupt more calmly (effusive eruption). Sinabung (Indonesia) Mount Sinabung is a stratovolcano located 40 km from the Lake Toba supervolcano in North Sumatra. It lies along the Sunda Arc, where the Indo-Australian plate subducts beneath the Sunda and Burma plates. After 1200 years of dormancy, Sinabung began erupting intermittently in 2010. Major eruptions have occurred regularly since November 2013. In November and December 2015, ash plumes reached 6 – 11 km in height on multiple occasions. Pyroclastic flows and ashfall blanketed the region in January 2014 and lava flows travelled down the south flank, advancing 2.5 km by April 2014. Pyroclastic flows in February 2014 killed 17 people in a town 3 km from the vent. In June 2015, ash falls affected areas 10 – 15 km from the summit on many occasions. A lahar in May 2016, caused fatalities in a village 20 km from Sinabung. Pyroclastic flows occurred frequently throughout 2016 and 2017 Eruption of Sinabung 6 October 2016 Major eruptions occurred in 2018 and 2019. In (Y Ginsu, public domain) February 2018, an eruption destroyed a lava dome of 1.6 million cubic metres. At least 10 pyroclastic flows extended up to 4.9 km and an ash plume rose more than 16 km in altitude. -

Three-Dimensional Magmatic Architecture of a Buried Shield Volcano

https://doi.org/10.1130/G47941.1 Manuscript received 22 January 2020 Revised manuscript received 24 August 2020 Manuscript accepted 29 August 2020 © 2020 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 12 October 2020 Inside the volcano: Three-dimensional magmatic architecture of a buried shield volcano Faye Walker1*, Nick Schofield1, John Millett1,2, Dave Jolley1, Simon Holford3, Sverre Planke2,4, Dougal A. Jerram4,5 and Reidun Myklebust6 1 Geology and Petroleum Geology, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK 2 Volcanic Basin Petroleum Research, Blindernveien 5, N-0361 Oslo, Norway 3 Australian School of Petroleum, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia 4 Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, N-0315 Oslo, Norway 5 DougalEARTH Ltd., Solihull B91 3NU, UK 6 TGS, Asker N-1386, Norway ABSTRACT its magma chamber have never been imaged in The nature and growth of magmatic plumbing systems are of fundamental importance detail before. to igneous geology. Traditionally, magma chambers have been viewed as rapidly emplaced Magma chambers have traditionally been bodies of molten rock or partially crystallized “magma mush” connected to the surface viewed as large, long-lived, geometrically sim- by a narrow cylindrical conduit (referred to as the “balloon-and-straw” model). Recent ple bodies of molten rock, which are emplaced data suggest, however, that magma chambers beneath volcanoes are formed incrementally rapidly and slowly crystallize to form plutons through amalgamation of smaller intrusions. Here we present the first high-resolution three- (Glazner et al., 2004; Annen et al., 2015; Jerram dimensional reconstruction of an ancient volcanic plumbing system as a large laccolithic and Bryan, 2018; Sparks et al., 2019). -

Igneous Activity and Volcanism Homework

DATE DUE: Name: Ms. Terry J. Boroughs Geology 300 Section: IGNEOUS ROCKS AND IGNEOUS ACTIVITY Instructions: Read each question carefully before selecting the BEST answer. Use GEOLOGIC vocabulary where applicable! Provide concise, but detailed answers to essay and fill-in questions. TURN IN YOUR 882 –ES SCANTRON AND ANSWER SHEET ONLY! MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS: 1. Gabbro and Granite a. Have a similar mineral composition b. Have a similar texture c. Answers A. and B. d. Are in no way similar 2. Which of the factors listed below affects the melting point of rock and sediment? a. Composition of the material d. Water content b. The confining pressure e. All of the these c. Only composition of the material and the confining pressure 3. Select the fine grained (aphanitic) rock, which is composed mainly of sodium-rich plagioclase feldspar, amphibole, and biotite mica from the list below: a. Basalt b. Andesite c. Granite d. Diorite e. Gabbro 4. __________ is characterized by extremely coarse mineral grains (larger than 1-inch)? a. Pumice b. Obsidian c. Granite d. Pegmatite 5. Basalt exhibits this texture. a. Aphanitic b. Glassy c. Porphyritic d. Phaneritic e. Pyroclastic 6. Rocks that contain crystals that are roughly equal in size and can be identified with the naked eye and don’t require the aid of a microscope, exhibits this texture: a. Aphanitic b. Glassy c. Porphyritic d. Phaneritic e. Pyroclastic 7. The texture of an igneous rock a. Is controlled by the composition of magma. b. Is the shape of the rock body c. Determines the color of the rock d. -

3D Seismic Imaging of the Shallow Plumbing System Beneath the Ben Nevis 2 Monogenetic Volcanic Field: Faroe-Shetland Basin 3 Charlotte E

ArticleView metadata, text citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Click here to download Article text Ben Nevis Paperbrought to you by CORE MASTER.docx provided by Aberdeen University Research Archive Plumbing systems of monogenetic edifices 1 3D seismic imaging of the shallow plumbing system beneath the Ben Nevis 2 Monogenetic Volcanic Field: Faroe-Shetland Basin 3 Charlotte E. McLean1*; Nick Schofield2; David J. Brown1, David W. Jolley2, Alexander Reid3 4 1School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, Gregory Building, University of Glasgow, G12 8QQ, UK 5 2Department of Geology and Petroleum Geology, University of Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK 6 3Statoil (U.K.) Limited, One Kingdom Street, London, W2 6BD, UK 7 *Correspondence ([email protected]) 8 Abstract 9 Reflective seismic data allows for the 3D imaging of monogenetic edifices and their 10 corresponding plumbing systems. This is a powerful tool in understanding how monogenetic 11 volcanoes are fed and how pre-existing crustal structures can act as the primary influence 12 on their spatial and temporal distribution. This study examines the structure and lithology of 13 host-rock as an influence on edifice alignment and provides insight into the structure of 14 shallow, sub-volcanic monogenetic plumbing systems. The anticlinal Ben Nevis Structure 15 (BNS), located in the northerly extent of the Faroe-Shetland Basin, NE Atlantic Margin, was 16 uplifted during the Late Cretaceous and Early Palaeocene by the emplacement of a laccolith 17 and a series of branching sills fed by a central conduit. Seismic data reveals multiple 18 intrusions migrated up the flanks of the BNS after its formation, approximately 58.4 Ma 19 (Kettla-equivalent), and fed a series of scoria cones and submarine volcanic cones. -

Explosive Eruptions

Explosive Eruptions -What are considered explosive eruptions? Fire Fountains, Splatter, Eruption Columns, Pyroclastic Flows. Tephra – Any fragment of volcanic rock emitted during an eruption. Ash/Dust (Small) – Small particles of volcanic glass. Lapilli/Cinders (Medium) – Medium sized rocks formed from solidified lava. – Basaltic Cinders (Reticulite(rare) + Scoria) – Volcanic Glass that solidified around gas bubbles. – Accretionary Lapilli – Balls of ash – Intermediate/Felsic Cinders (Pumice) – Low density solidified ‘froth’, floats on water. Blocks (large) – Pre-existing rock blown apart by eruption. Bombs (large) – Solidified in air, before hitting ground Fire Fountaining – Gas-rich lava splatters, and then flows down slope. – Produces Cinder Cones + Splatter Cones – Cinder Cone – Often composed of scoria, and horseshoe shaped. – Splatter Cone – Lava less gassy, shape reflects that formed by splatter. Hydrovolcanic – Erupting underwater (Ocean or Ground) near the surface, causes violent eruption. Marr – Depression caused by steam eruption with little magma material. Tuff Ring – Type of Marr with tephra around depression. Intermediate Magmas/Lavas Stratovolcanoes/Composite Cone – 1-3 eruption types (A single eruption may include any or all 3) 1. Eruption Column – Ash cloud rises into the atmosphere. 2. Pyroclastic Flows Direct Blast + Landsides Ash Cloud – Once it reaches neutral buoyancy level, characteristic ‘umbrella cap’ forms, & debris fall. Larger ash is deposited closer to the volcano, fine particles are carried further. Pyroclastic Flow – Mixture of hot gas and ash to dense to rise (moves very quickly). – Dense flows restricted to valley bottoms, less dense flows may rise over ridges. Steam Eruptions – Small (relative) steam eruptions may occur up to a year before major eruption event. . -

Origin of Gabbroic Xenoliths Within the Lone Mountain Dacite Intrusion, Big Sky, Montana: a Field and Petrographic Analysis Emily Clement

Undergraduate Review Volume 2 Article 28 2006 Origin of Gabbroic Xenoliths within the Lone Mountain Dacite Intrusion, Big Sky, Montana: A Field and Petrographic Analysis Emily Clement Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the Geochemistry Commons, and the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Clement, Emily (2006). Origin of Gabbroic Xenoliths within the Lone Mountain Dacite Intrusion, Big Sky, Montana: A Field and Petrographic Analysis. Undergraduate Review, 2, 214-222. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol2/iss1/28 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2006 Emily Clement ,>4 Origin ofGabbroic Xenoliths within the Lone Mountain Dacite Intrusion, Big Sky, Montana: A Field and Petrographic Analysis BY EMILY CLEMENT Emily is an Earth Science major graduating Abstract in 2006. Her project, funded with an AlP one Mountain represents a dacite laccolith that intruded in Late gran, allowed her to conduct research in Cretaceous time -68 Ma. This intrusion resulted in contact meta· the lab at Big Sky, Montana. She and her morphism of the sedimentary country rock resulting in formation mentor, Dr. Michael Krol, are continuing L ofa thin zone of black hornfels. Field work reveals the presence of to research both geochemical and micro abundant, 1~9 em sized gabbro xenoliths and lesser amounts of siltstone inclu structural analysis. sions within the dacite intrusion. Compositionally, the Lone Mountain dacite consists of hornblende + plagioclase + biotite + quartz + opaques. Whereas the gabbroic xenoliths consist of pyroxene + hornblende + plagioclase + minor chlorite. This study is concerned with the origin of the gabbroic xenoliths and their relation to the dacite intrusion. -

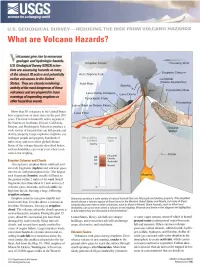

What Are Volcano Hazards?

USGS science for a changing world U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS What are Volcano Hazards? \7olcanoes give rise to numerous T geologic and hydrologic hazards. Eruption Cloud Prevailing Wind U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scien tists are assessing hazards at many Eruption Column of the almost 70 active and potentially Ash (Tephra) Fall active volcanoes in the United Landslide (Debris Avalanche) States. They are closely monitoring Acid Rain Bombs activity at the most dangerous of these Pyroclastic Flow volcanoes and are prepared to issue Lava Dome Collapse x Lava Dome warnings of impending eruptions or Pyroclastic Flow other hazardous events. Lahar (Mud or Debris Flow)jX More than 50 volcanoes in the United States Lava Flow have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years. The most volcanically active regions of the Nation are in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Washington. Volcanoes produce a wide variety of hazards that can kill people and destroy property. Large explosive eruptions can endanger people and property hundreds of miles away and even affect global climate. Some of the volcano hazards described below, such as landslides, can occur even when a vol cano is not erupting. Eruption Columns and Clouds An explosive eruption blasts solid and mol ten rock fragments (tephra) and volcanic gases into the air with tremendous force. The largest rock fragments (bombs) usually fall back to the ground within 2 miles of the vent. Small fragments (less than about 0.1 inch across) of volcanic glass, minerals, and rock (ash) rise high into the air, forming a huge, billowing eruption column. -

Explosive Caldera-Forming Eruptions and Debris-Filled Vents: Gargle Dynamics Greg A

https://doi.org/10.1130/G48995.1 Manuscript received 26 February 2021 Revised manuscript received 15 April 2021 Manuscript accepted 20 April 2021 © 2021 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Explosive caldera-forming eruptions and debris-filled vents: Gargle dynamics Greg A. Valentine* and Meredith A. Cole Department of Geology, University at Buffalo, 126 Cooke Hall, Buffalo, New York 14260, USA ABSTRACT conservation equations solved for both gas and Large explosive volcanic eruptions are commonly associated with caldera subsidence and particles, which are coupled through momentum ignimbrites deposited by pyroclastic currents. Volumes and thicknesses of intracaldera and (drag) and heat exchange (as in Sweeney and outflow ignimbrites at 76 explosive calderas around the world indicate that subsidence is com- Valentine, 2017; Valentine and Sweeney, 2018). monly simultaneous with eruption, such that large proportions of the pyroclastic currents The same approach was used to study discrete are trapped within the developing basins. As a result, much of an eruption must penetrate phreatomagmatic explosions in debris-filled its own deposits, a process that also occurs in large, debris-filled vent structures even in the vents (Sweeney and Valentine, 2015; Sweeney absence of caldera formation and that has been termed “gargling eruption.” Numerical et al., 2018), but here we focus on sustained dis- modeling of the resulting dynamics shows that the interaction of preexisting deposits (fill) charges. The simplified two-dimensional (2-D), with an erupting (juvenile) mixture causes a dense sheath of fill material to be lifted along axisymmetric model domain extends to an alti- the margins of the erupting jet. -

Basaltic Explosive Volcanism: Constraints from Deposits and Models B.F

ARTICLE IN PRESS Chemie der Erde 68 (2008) 117–140 www.elsevier.de/chemer INVITED REVIEW Basaltic explosive volcanism: Constraints from deposits and models B.F. HoughtonÃ, H.M. Gonnermann Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA Received 13 March 2008; accepted 10 April 2008 Abstract Basaltic pyroclastic volcanism takes place over a range of scales and styles, from weak discrete Strombolian 2 3 1 7 8 1 explosions ( 10 –10 kg sÀ ) to Plinian eruptions of moderate intensity (10 –10 kg sÀ ). Recent well-documented historical eruptions from Etna, Kı¯lauea and Stromboli typify this diversity. Etna is Europe’s largest and most voluminously productive volcano with an extraordinary level and diversity of Strombolian to subplinian activity since 1990. Kı¯lauea, the reference volcano for Hawaiian fountaining, has four recent eruptions with high fountaining (4400 m) activity in 1959, 1960, 1969 (–1974) and 1983–1986 (–2008); other summit (1971, 1974, 1982) and flank eruptions have been characterized by low fountaining activity. Stromboli is the type location for mildly explosive Strombolian eruptions, and from 1999 to 2008 these persisted at a rate of ca. 9 per hour, briefly interrupted in 2003 and 2007 by vigorous paroxysmal eruptions. Several properties of basaltic pyroclastic deposits described here, such as bed geometry, grain size, clast morphology and vesicularity, and crystal content are keys to understand the dynamics of the parent eruptions. The lack of clear correlations between eruption rate and style, as well as observed rapid fluctuations in eruptive behavior, point to the likelihood of eruption style being moderated by differences in the fluid dynamics of magma and gas ascent and the mechanism by which the erupting magma fragments.