The Burial Custom of Cremation and the Warrior Order Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Imxpd 2Mxpd IIS

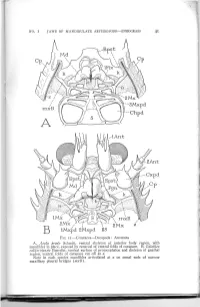

NO. I JAWS OF MANDIBULATE ARTHROPODS SNODGRASS 41 2Mx 2 IMxpd 2Mxpd IIS FIG. II.—Crustacea—Decapoda: Anomura A, Aegla prado Schmitt, ventral skeleton of anterior body region, with mandibles in place, exposed by removal of ventral folds of carapace. B, Galathea calijorniensis Benedict, ventral surface of protocephalon and skeleton of gnathal region, ventral folds of carapace cut off at s. Note in each species mandibles articulated at a on mesal ends of narrow maxillary pleural bridges {mxB). 42 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. Il6 FIG. 12.—Crustacea—Decapoda: Anomura. A, Petrolisthes criomerus Stimpson, epistomal region and mandibles, dorsal (interior) view, showing mandibles articulated at a on remnants of maxillary bridges (mxb). B, same, right mandible, ventral. C, Galathea calif orniensis Benedict, muscles of mandibular apodeme arising on carapace. D, same, right mandible, dorsal. E, Pagunts pollicaris Say, left mandible in position of adduc tion, ventral. F, same, same mandible in position of abduction. G, same, distal part of left mandible, showing articulation on epistome. H, Galathea calif orni ensis Benedict, right mandible and its skeletal supports, ventral. ••MMM NO. I JAWS OF MANDIBULATE ARTHROPODS—-SNODGEASS 43 of the mouth folds (fig. i6 E, t), each of which at its distal end divides into a mesal branch that goes into the paragnath (Pgn), and a lateral branch that supports the mandible by means of a small inter vening sclerite (E, H, e). The connection on the mandible is with a process behind the base of the gnathal lobe (figs. 12 D; 15 C, D, F, G; 16 A, B, G, H, d), a feature characteristic of anomuran and brachyuran mandibles; in most cases the metastomal arm makes a direct contact with the mandibular process. -

Education • Ph.D. Candidate in History of Art, University of Crete Supervisor

Afroditi Kouki Research Team Member CV Date of birth: 29 August 1981 Telephone number:+30-6972398607 E-mail: [email protected] Education • Ph.D. Candidate in History of Art, University of Crete Supervisor: Professor Evgenios Matthiopoulos Ph.D. Dissertation (in progress): “The Creation and Organisation of the Production of Folk Art Works: From ‘The Feast in the Zappeion Exhibition Hall’ by the Lyceum Club of Greek Women (1911) to the Professional School of Housekeeping and Handicraft ‘The Greek House’ (1938)” • M.A. in History of Art, University of Crete, 2003-2008 Supervisor: Professor Evgenios Matthiopoulos Grade: “Excellent” (9/10) M.A. Thesis: “The Organisation of the Production of Folk Art Works during the Interwar Period: from the ‘Lyceum Club of Greek Women’ to the ‘Association of Arts and Crafts Workshops’” • B.A. in Archaeology and Art History, University of Crete, 1999-2003 Grade: “Very Good” (Lian Kalos, 7.79/10) Grant • Foundation for Research and Technology-Hellas (FORTH) – Institute for Mediterranean Studies: Participation in the research project “Art criticism in interwar Greece”, 2007-2009 (principal researcher: Professor Evgenios Matthiopoulos) Publication • ‘Folk’ art in the ‘service’ of bourgeois modernization: the proposals of the German architect Hugo Eberhardt for the development of Greek craft industry (1914)”, in Research questions in art history, from the late Middle Ages to the present day, Aris Sarafianos & Panagiotis Ioannou (eds), Athens: Asini Publishing, 2016, p. 329-342 Conference papers • “Proposals -

Honeymoon & Gastronomy2

Explore Kapsaliana Village Learn More Kapsaliana Village Hotel HISTORY: Welcome at Kapsaliana Village Hotel, a picturesque village in The story begins at the time of the Venetian Occupation. Kapsaliana Rethymno, Crete that rewrites its history. Set amidst the largest olive Village was then a ‘metochi’ - part of the Arkadi Monastery estate, the grove in the heart of the island known for its tradition, authenticity and island’s most emblematic cenobium. natural landscape. Around 1600, a little chapel dedicated to Archangel Michael is Located 8km away from the seaside and 4km from the historic Arkadi constructed and a hamlet began to develop. More than a century monastery. Kapsaliana Village Hotel is a unique place of natural beauty, later, in 1763, Filaretos, the Abbot of Arkadi Monastery decides to peace and tranquility, where accommodation facilities are build an olive oil mill in the area. harmonised with the enchanting landscape. The olive seed is at the time key to the daily life: it is a staple of Surrounded by lush vegetation, unpaved gorges and rare local herbs nutricion, it is used in religious ceremonies and it functions as a source and plants. Kapsaliana Village Hotel overlooks the Cretan sea together of light and heat. with breathtaking views of Mount Ida and the White Mountains. More and more people come to work at the mill and build their The restoration of Kapsaliana Village hotel was a lengthy process which houses around it. The settlement flourishes. At its peak Kapsaliana took around four decades. When the architect Myron Toupoyannis, Village Hotel boasts 13 families and 50 inhabitants with the monk- discovered the ruined tiny village, embarked on a journey with a vision steward of the Arkadi monastery in charge. -

Nsc Notizie Degli Scavi Di Antichità OJA Oxford Journal of Archaeology

ABBREVIATIONS xiii NSc Notizie degli scavi di antichità OJA Oxford Journal of Archaeology PastPres Past and Present PBSR Papers of the British School at Rome PCPS Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society PP La parola del passato QSAP Quaderni della Soprintendenza di Archeologia nella Piemonte RE Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft REA Revue des études anciennes RÉg Revue d’égyptologie RIG II.1 M. Lejeune 1985. Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloise, vol. II.1. Textes gallo-grecs (Paris). RIG IV J.-B. Colbert de Beaulieu and B. Fischer 1998. Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises, vol. IV. Les légendes monétaires (Paris). RMD I M. M. Roxan, Roman military diplomas 1954-1977 (London) RSL Rivista di Studi Liguri. ScAnt Scienze dell’Antichità: Storia, archeologia, antropologia SCO Studi Classici e Orientali SEG Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum SHAJ Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan SIG3 W. Dittenberger, Sylloge inscriptionum graecarum (Leipzig 1883– ) ST H. Rix, Sabellische Texte: die Texte des Oskischen, Umbrischen und Südpikenischen (Heidelberg, 2002). StEtr Studi Etruschi TAPA Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philosophical Association WorldArch World Archaeology TMArchives Papyrus archives in Graeco-Roman Egypt (Leuven Homepage of Papyrus Archives), online at: http://www.trismegistos.org/arch/index/php ZDPV Zeitschrift des deutschen Palästina-Vereins ZPE Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik The standard abbreviations of papyri are listed in J. D. Sosin et al. (edd.), Checklist -

A New Cavernicolous Species of the Pseudoscorpion Genus Roncus L

Int. J. Speleol. 5 (1973), pp. 127-134. A New Cavernicolous Species of the Pseudoscorpion Genus Roncus L. Koch, 1873 (Neobisiidae, Pseudoscorpiones) from the Balkan Peninsula by Bozidar P.M. CURtlC * The range of the pseudoscorpion subgenus Parablothrlls Beier 1928 (from the genus Roncus L. Koch 1873) extends over the northern Mediterranean, covering a vast zone from Catalonia on the west as far as Thrace on the east. The northern limit of distribution of these false scorpions is situated within the Dolomites and the Alps of Carinthia; the most southern locations of the subgenus were registered on the island of Crete. Eight species of Parablothrus are known to inhabit the Balkan Peninsula which represents an impo;:tant distribution centre of the subgenus (Beier 1963, Helversen 1969); of them, six were found in the Dinaric Karst. The caves of Carniola are thus populated by R. (F:) stussineri (Simon) 1881, and R. (P) anophthalmus (Ellingsen) 1910, R. (P.) cavernicola Beier 1928 and R. (P) vulcanius Beier 1939 are known from Herzegovina. The last species was also collected on some Dalmatian islands. Both Adriatic and Ionian islands are inhabited by two other members of Parablo- thrus, namely R. (P.) insularis Beier 1939 (which was found on the isle of Brae) and R. (P) corcyraeus Beier 1963, the latter living on Corfu. Except for the Dinaric elements of Parablothrus, the Balkan representatives of the subgenus have not been sufficiently studied. In spite of this, one may assume that the differentiation of cave living species of Roncus took place both east and north of the peninsula. -

Exhibition Object List

OBJECT LIST Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections April 9–August 25, 2014 At the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Villa 1. Bowl (for Kandela) 5. Earring Greek, modern Greek, A.D. 400-500 From Greece From Egypt, Antinoë Glass Gold, emerald, amethyst, Diam.: 4 7/8 in. sapphire, and pearl Tositsa Baron Museum H: 3 7/16 in. T.2014.1 Benaki Museum VEX.2014.2.3.2 2. Ivory relief with Dioskouros, A.D. 400s 6. Earring From Greece, Athens Greek, A.D. 400-600 Ivory and gold From Greece H: 7 1/2 x 3 7/16 x 13/16 in. Gold, sapphire, pearl and glass Acropolis Museum paste VEX.2014.2.1 H: 3 13/16 in. Benaki Museum 3. Necklace VEX.2014.2.4.1 Greek, A.D. 400-500 From Egypt, Antinoë 7. Earring Gold, emerald, amethyst, Greek, A.D. 400-600 sapphire, and pearl From Greece L: 16 7/8 in. Gold, sapphire, pearl and glass Benaki Museum paste VEX.2014.2.2 H: 3 13/16 in. Benaki Museum 4. Earring VEX.2014.2.4.2 Greek, A.D. 400-500 From Egypt, Antinoë Gold, emerald, amethyst, sapphire, and pearl H: 3 7/16 in. Benaki Museum VEX.2014.2.3.1 Page 2 8. Bracelet 13. Unknown maker, Greek Greek, A.D. 500s The Hospitality of Abraham, From Greece, Cyprus About A.D. 1375-1400 Gold Tempera and gold on wood Benaki Museum 14 3/16 x 24 1/2 x 1 in. VEX.2014.2.5 Benaki Museum VEX.2014.2.10 9. -

Morphometric Characteristics of Crayfish Cherax Quadricarinatus from Atokan River, West Sumatera, Indonesia

Eco. Env. & Cons. 26 (4) : 2020; pp. (1787-1792) Copyright@ EM International ISSN 0971–765X Morphometric characteristics of Crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus from Atokan River, West Sumatera, Indonesia Abizar1, Lora Purnamasari1, Widyawati1, Moch Affandi2 and Trisnadi Widyaleksono Catur Putranto2* 1 Study Program of Biology Education, STKIP PGRI Sumatera Barat (College of Teacher Training and Education), Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia (Received 5 April, 2020; Accepted 20 June, 2020) ABSTRACT The objectives of this study were to determine the length–weight relationships (LWRs), sexual dimorphism and condition factors (K) of Cherax quadricarinatus from Atokan River, West Sumatera Indonesia. The sex ratio of C. quadricarinatus was: 1.3:1 (Males:females). Males and females’ crayfish exhibited negative allometric growth (b<3). The length–weight regression was not significantly different between males and females. The condition factor (K) for males and females were 2.85 and 2.32 respectively. There was no significant difference between weight of males and females, however the total length of females was longer than male. There was no significant difference between length and weight of males and females. Carapace width of males and females were not significantly different, meanwhile carapace length of female was longer than the male. The chelae length and chelae width of males and females were not significantly different. This study provides baseline information on morphometric characteristic of C. quadricarinatus in Atokan River, which will be useful for further reference such as management and conservation of the crayfish. Key words : Redclaw, Growth, Sexual dimorphism, Atokan river, West Sumatera. -

Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials

MORTUARY VARIABILITY IN EARLY IRON AGE CRETAN BURIALS Melissa Suzanne Eaby A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Donald C. Haggis Carla M. Antonaccio Jodi Magness G. Kenneth Sams Nicola Terrenato UMI Number: 3262626 Copyright 2007 by Eaby, Melissa Suzanne All rights reserved. UMI Microform 3262626 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © 2007 Melissa Suzanne Eaby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MELISSA SUZANNE EABY: Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials (Under the direction of Donald C. Haggis) The Early Iron Age (c. 1200-700 B.C.) on Crete is a period of transition, comprising the years after the final collapse of the palatial system in Late Minoan IIIB up to the development of the polis, or city-state, by or during the Archaic period. Over the course of this period, significant changes occurred in settlement patterns, settlement forms, ritual contexts, and most strikingly, in burial practices. Early Iron Age burial practices varied extensively throughout the island, not only from region to region, but also often at a single site; for example, at least 12 distinct tomb types existed on Crete during this time, and both inhumation and cremation were used, as well as single and multiple burial. -

Museum of Ancient Eleutherna Homer in Crete

HOMER IN CRETE Model of the Museum of Ancient Eleutherna he project with the title “Building For information please contact: TComplex of the Museum of the Archaeological Site of Eleutherna – Itinerary”, Museum of the Archaeological Site ANCIENT ELEUTHERNA MUSEUM OF was implemented through the European of Eleutherna Operational Programme “Competitiveness Address: Eleutherna Rethymno 74052 Crete and Entrepreneurship 2007-2013” (NSRF) by Tel. and FAX: +03028340-92501 its operators the University of Crete and the Ministry of Culture and Sports. Mediterranean Archaeological Society (M.A.S.) his effort was also supported by private Address: Β. Hali 8, Rethymno 74100 Crete Tinitiative (Members of Excellency of Chatzichristou 14 Athens 11742 the Mediterranean Archaeological Society, Tel. +030-2130358884 Organisms, Foundations and private e-mail: [email protected] individuals). [email protected] http://mae.com.gr MUSEUM OF ANCIENT ELEUTHERNA Ancient Eleutherna secrets, which date from approximately in the Louvre in Paris. grave gifts of weapons, jewellery, films and audiovisual presenta- 3000 BC to the fourteenth century AD. Room C is dedicated to Eleuth- and tools. This tomb contained tions enhance the museum’s t approximately 380m above sea level, Excavations at the Orthi Petra necropolis erna’s cemeteries. The display the bronze shield now on dis- evocative exhibits. Aon the slopes of Mount Ida (Psiloritis), show that the Early Iron Age, particularly focuses on finds from the Orthi play as an emblem in the muse- Eleutherna stands on a prominence that re- the period from 900 BC to the end of the Petra necropolis, since these il- um’s entrance. Contacts and exchange be- sembles a vast stone ship moored in ineffa- 6th or beginning of the 5th century BC, lustrate the Homeric narrative, The display ends with a recon- tween East and West in antiq- ble green with its prow pointing northwest. -

Communications

Volume 39 Issue 8 November 2012 Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati Editor: Carol Hershenson P.O. Box 0226, Cincinnati, Ohio, 45221-0226, U.S.A. Assistant Editors: P. Tyler Haas and http://classics.uc.edu/nestor Charlotte Lakeotes [email protected] COMMUNICATIONS Calls for Papers On 30 November 2012 abstracts (250 words maximum) are due for a conference entitled Island, mainland, coastland & hinterland: ceramic perspectives on connectivity in the ancient Mediterranean, to be held at the University of Amsterdam on 1-2 February 2013. Abstracts should be sent to [email protected]. Further information and reGistration forms are available at http://npap.nl. Theoretically informed papers embracinG (but not restricted to) the followinG themes are invited: The relationship between Geographical setting, ceramic assemblaGes and deGree of connectivity between different communities The role Geographical and/or socio-political entities such as ‘hinterland’ or ‘colony’ play in interpreting ceramic assemblaGes How can we interpret stylistic or technological ceramic ‘hybrids’ with respect to the movement of people, artefacts and ideas? Can we identify in the ceramic record deliberate participation within or rejection/resistance to wider socio-cultural phenomena? On 15 December 2012 member-organized session proposals are due for the American Schools of Oriental Research Annual Meetings (ASOR 2013), to be held in Baltimore, MD on 20-23 November 2013. On 15 February 2013, or 1 March with an administrative fee, abstract submissions are due. On 15 August 2013 messages of intention are due for participation in the Projects on Parade poster session. Further information and all forms are available at http://www.asor.org. -

The Region of Rethymno

EU Community Initiative Programme Intereeg III B ARCHIMED DI.MA “Discovering Magna Grecia” The Greek-Byzantine Mediterranean itineraries – The Region of Rethymno General Information The town of Rethymnon, capital of the homonym prefecture, is located between the towns of Chania and Herakleion. It lies along the north coast, having to the east one of the largest sand beaches of Crete (length: 12 km) and to the west a rocky coastline that ends up to another large sand beach. To the North is the Cretan and to the South the Libyan Sea. In the east rises the mount of Psiloritis (Ida) and in the south - west the mountain range of Kedros. Between the two massifs is the valley of Amari. On the north - easterly border of the prefecture rises the mount of Kouloukonas (Talaia Mountain). South of the town is the mount of Vrisinas and in a south westerly direction lies the mount of Kryoneritis. Access Airports: Rethymnon is served by the airports of Chania and Heraklion. Port: There is direct connection all year round from the port of Rethymnon to Piraeus. Buses: Public buses can be used daily for travelling to Chania, Heraklion, Siteia and to the most of the townships and villages of the prefecture of Rethymnon. Highways: The main transport routes in the province are a) the new national highway which runs parallel with the north coast, b) the old national highway, which is situated slightly south of the new road, and c) Rethymnon - Spili - Agia Galini - Sfakia road which runs north –south. Natural Geography Rethymnon stretches from the White Mountains until Mount Psiloritis, bordered by the provinces of Hania and Iraklion. -

Map 53 Bosphorus Compiled by C

Map 53 Bosphorus Compiled by C. Foss, 1995 Introduction (See Map 52) Directory All place names are in Turkey Abbreviation DionByz R. Güngerich (ed.), Dionysii Byzantii Anaplus Bospori, 1927 (reprint, Berlin, 1958) Names Grid Name Period Modern Name / Location Reference Aianteion See Lettered Place Names B2 Aietou Rhynkos Pr. R Yalıköy RE Bosporos 1, col. 753 B2 Akoimeton Mon. L at Eirenaion Janin 1964, 486-87 C3 Akritas Pr. RL Tuzla burnu FOA VIII, 2 A3 Ammoi L E Bakırköy Janin 1964, 443 B2 Amykos HR Beykoz RE Bosporos 1, col. 753 B2 Anaplous?/ L/ Arnavutköy Janin 1964, 468, 477-78 Promotou? L B2 Ancyreum Pr. R Yum burnu RE Bosporos 1, col. 752 B3 [Antigoneia] Ins. Burgaz ada RE Panormos 7 B2 Aphrodysium R Çalı Burnu RE Bosporos 1, col. 751 B2 Archeion R Ortaköy RE Bosporos 1, col. 747 B2 Argyronion RL Macar tabya RE Bosporos 1, col. 752-53 Argyropolis/ See Lettered Place Names Bytharion? Auleon? Sinus See Lettered Water Names Auletes See Lettered Place Names B2 ‘Bacca’ Collis R N Kuruçesme RE Bosporos 1, col. 747 B2 Bacchiae/ C/ Koybaşı RE Bosporos 1, col. 748 Thermemeria HR A2 Barbyses fl. RL Kâgithane deresi RE Bathykolpos See Lettered Water Names B2 *Bathys fl. R Büyükdere DionByz 71; GGM II, 54 B2 Bithynia See Map 52 A2 Blachernai RL Ayvansaray RE; Janin 1964, 57-58 Bolos See Lettered Place Names B2 Boradion L above Kanlıca Janin 1964, 484 B2 Bosphorus RL Bogaziçi RE Bosporos 1; NPauly Bosporos 1 §Bosporos CHRL Bosporion = Phosphorion A2 Bosporios Pr. R Saray burnu RE Βοσπόριος ἄκρα A2 Boukolos Collis R DionByz 25; C.