Of Greeks and Arabs and of Feudal Knights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGATHÓNAGATHÓN RFCA Phd Journal Recupero E Fruizione Dei Contesti Antichi

Università degli Studi di Palermo Dipartimento di Progetto e Costruzione Edilizia AGATHÓNAGATHÓN RFCA PhD Journal Recupero e Fruizione dei Contesti Antichi 2010/1 Continues in this edition of Agathón the enlargement of the Scientific Committee with A G A T H Ó N the Researchers from other countries, in order to compare different international expe- RFCA PhD Journal riences: Tarek Brik, architect and professor at l’ENAU of Tunis, and Josep Burch ar- Recupero e Fruizione dei Contesti Antichi chaeologist and professor at Girona University. The first Section, Agorà, as the main and collective space in Greek polis, hosts the contributions of Gillo Dorfles, Chiara Visentin, Josep Burch, David Palterer, and mine. In the Section, Stoà, as the porch where the philosopher Zeno taught his disciples, are gi- ven the contributions presentated by teachers of Doctoral College: Maria Clara Ruggie- ri, Renzo Lecardane and Cesare Sposito. In the third Section, Gymnasion as a place where young Greeks practiced gymnastics and where educated in arts and philosophy, are the contributions of Angela Katiuscia Sferrazza, Maria Désirée Vacirca, Santina Di Salvo, Alessandro Tricoli and Golnaz Ighani. The fourth Section, Sekós, as a room of Greek house for youn people mentioned by Plato (Rep. 460/c), has two young graduates, Federica Morella and Giorgio Faraci. We indicate, on back cover of the review, the ca- lendar of seminars of the years 2009/2010. 2010/1 Finally, we must remember that the editorial activity has been possible thanks to the Doctoral College, we specially thank, for their extraordinary work, Ph.D. Students San- dipartimento di tina Di Salvo and Maria Désirée Vacirca. -

Introduction – Grand Harbour Marina

introduction – grand harbour marina Grand Harbour Marina offers a stunning base in historic Vittoriosa, Today, the harbour is just as sought-after by some of the finest yachts Malta, at the very heart of the Mediterranean. The marina lies on in the world. Superbly serviced, well sheltered and with spectacular the east coast of Malta within one of the largest natural harbours in views of the historic three cities and the capital, Grand Harbour is the world. It is favourably sheltered with deep water and immediate a perfect location in the middle of the Mediterranean. access to the waterfront, restaurants, bars and casino. With berths for yachts up to 100m (325ft) in length, the marina offers The site of the marina has an illustrious past. It was originally used all the world-class facilities you would expect from a company with by the Knights of St John, who arrived in Malta in 1530 after being the maritime heritage of Camper & Nicholsons. exiled by the Ottomans from their home in Rhodes. The Galley’s The waters around the island are perfect for a wide range of activities, Creek, as it was then known, was used by the Knights as a safe including yacht cruising and racing, water-skiing, scuba diving and haven for their fleet of galleons. sports-fishing. Ashore, amid an environment of outstanding natural In the 1800s this same harbour was re-named Dockyard Creek by the beauty, Malta offers a cosmopolitan selection of first-class hotels, British Colonial Government and was subsequently used as the home restaurants, bars and spas, as well as sports pursuits such as port of the British Mediterranean Fleet. -

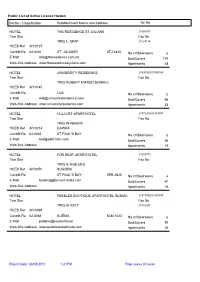

Public List of Active Licence Holders Tel No Sector / Classification

Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL THE RESIDENCE ST JULIANS 21360031 Two Star Fax No TRIQ L. APAP 21374114 HCEB Ref AH/0137 Contrib Ref 02-0044 ST. JULIAN'S STJ 3325 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 124 Web-Site Address www.theresidencestjulians.com Apartments 48 HOTEL UNIVERSITY RESIDENCE 21430360/21436168 Two Star Fax No TRIQ ROBERT MIFSUD BONNICI HCEB Ref AH/0145 Contrib Ref LIJA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 66 Web-Site Address www.universityresidence.com Apartments 33 HOTEL HULI CRT APARTHOTEL 21572200/21583741 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IN-NAKKRI HCEB Ref AH/0214 QAWRA Contrib Ref 02-0069 ST.PAUL'S BAY No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 56 Web-Site Address Apartments 19 HOTEL FOR REST APARTHOTEL 21575773 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IL-HGEJJEG HCEB Ref AH/0370 BUGIBBA Contrib Ref ST.PAUL'S BAY SPB 2825 No Of Bedrooms 4 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 40 Web-Site Address Apartments 16 HOTEL PEBBLES BOUTIQUE APARTHOTEL SLIEMA 21311889/21335975 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IX-XATT 21316907 HCEB Ref AH/0395 Contrib Ref 02-0068 SLIEMA SLM 1022 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 92 Web-Site Address www.pebbleshotelmalta.com Apartments 26 Report Date: 30/08/2019 1-21PM Page xxxxx of xxxxx Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL ALBORADA APARTHOTEL (BED & BREAKFAST) 21334619/21334563 Two Star 28 Fax No TRIQ IL-KBIRA -

Proposal for the Nomination of Lower Globigerina Limestone of the Maltese Islands As a “Global Heritage Stone Resource”

Article 221 by JoAnn Cassar1*, Alex Torpiano2, Tano Zammit1, and Aaron Micallef 3 Proposal for the nomination of Lower Globigerina Limestone of the Maltese Islands as a “Global Heritage Stone Resource” 1 Department of Conservation and Built Heritage, Faculty for the Built Environment, University of Malta, Msida MSD 2080, Malta; *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Architecture and Urban Design, Faculty for the Built Environment, University of Malta, Msida MSD 2080, Malta 3 Department of Geosciences, Faculty of Science, University of Malta, Msida MSD 2080, Malta (Received: June 21, 2016; Revised accepted: November 29, 2016) http://dx.doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2017/v40i3/017025 The Lower Globigerina Limestone of the Maltese Islands These will cover the nomination criteria that have been established by is here being proposed for nomination as a “Global Her- the Board of Management of the Heritage Stone Task Group (HSTG), itage Stone Resource”. This stone, continuously used for as specified in the Task Group’s checklist for “Global Heritage Stone building and sculpture for 6000 years, is well suited to fit Resource” designation (revised October 2014), and as reported on the this global designation as it is not only of great local cul- Global Heritage Stone website www.globalheritagestone.com. tural, historic and economic importance, but it is also the building stone used in construction of the UNESCO, and Criteria for GHSR Recognition hence internationally recognized, World Heritage city of Valletta, as well as the UNESCO-listed Prehistoric Mega- Criteria for designating a Global Heritage Stone Resource (GHSR) lithic Temples of the Maltese Islands. -

PDF Download Malta, 1565

MALTA, 1565: LAST BATTLE OF THE CRUSADES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Pickles,Christa Hook,David Chandler | 96 pages | 15 Jan 1998 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781855326033 | English | Osprey, United Kingdom Malta, 1565: Last Battle of the Crusades PDF Book Yet the defenders held out, all the while waiting for news of the arrival of a relief force promised by Philip II of Spain. After arriving in May, Dragut set up new batteries to imperil the ferry lifeline. Qwestbooks Philadelphia, PA, U. Both were advised by the yearold Dragut, the most famous pirate of his age and a highly skilled commander. Elmo, allowing Piyale to anchor his fleet in Marsamxett, the siege of Fort St. From the Publisher : Highly visual guides to history's greatest conflicts, detailing the command strategies, tactics, and experiences of the opposing forces throughout each campaign, and concluding with a guide to the battlefields today. Meanwhile, the Spaniards continued to prey on Turkish shipping. Tim Pickles describes how despite constant pounding by the massive Turkish guns and heavy casualties, the Knights managed to hold out. Michael across a floating bridge, with the result that Malta was saved for the day. Michael, first with the help of a manta similar to a Testudo formation , a small siege engine covered with shields, then by use of a full-blown siege tower. To cart. In a nutshell: The siege of Malta The four-month Siege of Malta was one of the bitterest conflicts of the 16th century. Customer service is our top priority!. Byzantium at War. Tim Pickles' account of the siege is extremely interesting and readable - an excellent book. -

Medieval Mdina 2014.Pdf

I Fanciulli e la Corte di Olnano This group was formed in 2002 in the Republic of San Marino. The original name was I Fanciulli di Olnano meaning the young children of Olnano, as the aim of the group was to explain history visually to children. Since then the group has developed Dolceria Appettitosa into a historical re-enactment group with adults Main Street and children, including various thematic sections Rabat within its ranks specializing in Dance, Singing, Tel: (00356) 21 451042 Embroidery, Medieval kitchen and other artisan skills. Detailed armour of some of the members of the group highlights the military aspects of Medieval times. Anakron Living History This group of enthusiasts dedicate their time to the re-enactment of the Medieval way of life by authentically emulating the daily aspects of the period such as socialising, combat practice and playing of Medieval instruments. The Medieval Tavern was the main centre of recreational, entertainment, gambling and where hearty home cooked meal was always to be found. Fabio Zaganelli The show is called “Lost in the Middle Ages”. Here Fabio acts as Fabius the Court Jester and beloved fool of the people. A playful saltimbanco and histrionic character, he creates fun and involves onlookers of all ages, Fabio never fails to amaze his audiences with high level circus skills and comedy acts, improvised dialogue plays and rhymes, poetry and rigmaroles. Fabio is an able juggler, acrobat, fakir and the way he plays with fi re makes him a real showman. BIBITA Bibita the Maltese minstrel band made their public Cafe’ Bistro Wine Bar debut at last year’s Medieval Festival. -

Vicino Oriente

VICINO ORIENTE SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA DIPARTIMENTO SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀ SEZIONE DI ORIENTALISTICA _________________________________________________________________________ VICINO ORIENTE XVII - 2013 ROMA 2013 VICINO ORIENTE SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA DIPARTIMENTO SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀ SEZIONE DI ORIENTALISTICA _________________________________________________________________________ Comitato Scientifico: Carlo Giovanni Cereti, Maria Vittoria Fontana, Lorenzo Nigro, Marco Ramazzotti, Arcangela Santoro Direttore Scientifico: Lorenzo Nigro Redazione: Daria Montanari, Chiara Fiaccavento Tipografia: SK7 - Roma ISSN 0393-0300 Rivista con comitato di referee Journal with international referee system www.lasapienzatojericho.it/SitoRivista/Journal/Rivista.php In copertina: mappa illustrata del mondo di H. Bünting, pubblicata in Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae, 1581. VICINO ORIENTE SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA DIPARTIMENTO SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀ SEZIONE DI ORIENTALISTICA _________________________________________________________________________ SOMMARIO ARTICOLI P. Gignoux - Souvenirs d’un grand savant: Gherardo Gnoli (1937-2012) 1 N.N.Z. Chegini - M.V. Fontana - A. Asadi - M. Rugiadi - A.M. Jaia - A. Blanco - L. Ebanista - V. Cipollari Estakhr Project - second preliminary report of the joint Mission of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research, the Parsa-Pasargadae Research Foundation and the Sapienza University of Rome, Italy 7 A. Asadi - S.M. Mousavi Kouhpar - J. Neyestani - A. Hojabri-Nobari - Sasanian and Early Islamic settlement patterns north of the Persian Gulf 21 L. Nigro - Before the Greeks: the earliest Phoenician settlement in Motya - recent discoveries by Rome «La Sapienza» Expedition 39 C. Fiaccavento - Potters’ wheels from Khirbet al-Batrawy: a reconsideration of social contexts 75 D. Montanari - A copper javelin head in the UCL Palestinian Collection 105 A. Massafra - A group of metal weapons from Tell el-‘Ajjul in the Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow 115 A. -

St-Paul-Faith-Iconography.Pdf

An exhibition organized by the Sacred Art Commission in collaboration with the Ministry for Gozo on the occasion of the year dedicated to St. Paul Exhibition Hall Ministry for Gozo Victoria 24th January - 14th February 2009 St Paul in Art in Gozo c.1300-1950: a critical study Exhibition Curator Fr. Joseph Calleja MARK SAGONA Introduction Artistic Consultant Mark Sagona For many centuries, at least since the Late Middle Ages, when Malta was re- Christianised, the Maltese have staunchly believed that the Apostle of the Gentiles Acknowledgements was delivered to their islands through divine intervention and converted the H.E. Dr. Edward Fenech Adami, H.E. Tommaso Caputo, inhabitants to Christianity, thus initiating an uninterrupted community of 1 Christians. St Paul, therefore, became the patron saint of Malta and the Maltese H.E. Bishop Mario Grech, Hon. Giovanna Debono, called him their 'father'. However, it has been amply and clearly pointed out that the present state of our knowledge does not permit an authentication of these alleged Mgr. Giovanni B. Gauci, Arch. Carmelo Mercieca, Arch. Tarcisio Camilleri, Arch. Salv Muscat, events. In fact, there is no historic, archaeological or documentary evidence to attest Arch. Carmelo Gauci, Arch. Frankie Bajada, Arch. Pawlu Cardona, Arch. Carmelo Refalo, to the presence of a Christian community in Malta before the late fourth century1, Arch. {u\epp Attard, Kapp. Tonio Galea, Kapp. Brian Mejlaq, Mgr. John Azzopardi, Can. John Sultana, while the narrative, in the Acts of the Apostles, of the shipwreck of the saint in 60 AD and its association with Malta has been immersed in controversy for many Fr. -

SEPTEMBER 2019 Priories

The BULLETIN The Order of St John of Jerusalem Knights Hospitaller THE GRAND PRIORY OF AUSTRALASIA Under the Royal Charter of HM King Peter II of Yugoslavia THE PRIORY OF QUEENSLAND AND COMMANDERIES: BRISBANE, GOLD COAST, SUNSHINE COAST AND WESTERN AUSTRALIA A centuries- old ceremony THE PRIORY OF THE DARLING DOWNS performed with grace and dignity, THE PRIORY OF VICTORIA welcoming 10 investees from three Queensland SEPTEMBER 2019 priories. Overseas Visitors 3 Pages 4-11 A Three-Priory Investiture 4 -11 Vancouver Meeting 2020 7 Elevations 2019 11 Victoria Investiture 12-14 Simulator for Life Flight 15 Brisbane Priory News 16 Footsteps of the Knights Tour 17 News and Events from WA 20 A Year of Celebration 22 Sunshine Coast News 24 THE BULLETIN EDITORIAL CHEVALIER CHARLES CLARK GCSJ MMSJ weekend a cocktail party celebrated 50 years of the Order of Saint John in Australia and a commemorative From the Editor’s desk medal was issued. A week later the Priory of Victoria held their Investiture Ceremony attended The three months be together. also by the Sovereign Order May to July this year have been In May the Commandery of representatives. All these unite an extra-ordinary time for the Western Australia was elevated to further our work for Christian Grand Priory of Australasia. It to Priory status, and so was the Charity. If it were not so, the writing has seen changes; changes in the Commandery of the Sunshine Coast. about them would be futile. way things are done, changes in New Members’ Night, an event Planning continues for fund- attitudes. -

The Otranto-Valona Cable and the Origins of Submarine Telegraphy in Italy

Advances in Historical Studies, 2017, 6, 18-39 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs ISSN Online: 2327-0446 ISSN Print: 2327-0438 The Otranto-Valona Cable and the Origins of Submarine Telegraphy in Italy Roberto Mantovani Department of Pure and Applied Sciences (DiSPeA), Physics Laboratory: Urbino Museum of Science and Technology, University of Urbino Carlo Bo, Urbino, Italy How to cite this paper: Mantovani, R. Abstract (2017). The Otranto-Valona Cable and the Origins of Submarine Telegraphy in Italy. This work is born out of the accidental finding, in a repository of the ancient Advances in Historical Studies, 6, 18-39. “Oliveriana Library” in the city of Pesaro (Italy), of a small mahogany box https://doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2017.61002 containing three specimens of a submarine telegraph cable built for the Italian Received: December 22, 2016 government by the Henley Company of London. This cable was used to con- Accepted: March 18, 2017 nect, by means of the telegraph, in 1864, the Ports of Otranto and Avlona (to- Published: March 21, 2017 day Valona, Albania). As a scientific relic, the Oliveriana memento perfectly fits in the scene of that rich chapter of the history of long distance electrical Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. communications known as submarine telegraphy. It is known that, thanks to This work is licensed under the Creative the English, the issue of submarine electric communication had an impressive Commons Attribution International development in Europe from the second half of the nineteenth century on. License (CC BY 4.0). Less known is the fact that, in this emerging technology field, Italy before uni- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ fication was able to carve out a non-negligible role for itself, although primar- Open Access ily political. -

Module 1 Gozo Today

Unit 1 - Gozo Today Josianne Vella Preamble: This first unit brings a brief overview of the Island’s physical and human geography, including a brief historic overview of the economic activities in Gozo. Various means of access to, and across the island as well as some of the major places of interest have been interspersed with information on the Island’s customs and unique language. ‘For over 5,000 years people have lived here, and have changed and shaped the land, the wild plants and animals, the crops and the constructions and buildings on it. All that speaks of the past and the traditions of the Islands, of the natural world too, is heritage.’ Haslam, S. M. & Borg, J., 2002. ‘Let’s Go and Look After our Nature, our Heritage!’. Ministry of Agriculture & Fisheries - Socjeta Agraria, Malta. The Island of Gozo Location: Gozo (Għawdex) is the second largest island of the Maltese Archipelago. The archipelago consists of the Islands of Malta, Gozo and Comino as well as a few other uninhabited islets. It is roughly situated in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about 93km south of Sicily, 350 kilometres due north of Tripoli and about 290 km from the nearest point on the North African mainland. Size: The total surface area of the Islands amounts to 315.6 square kilometres and are among the smallest inhabited islands in the Mediterranean. With a coastline of 47 km, Gozo occupies an area of 66 square kilometres and is 14 km at its longest and 7 km at its widest. IRMCo, Malta e-Module Gozo Unit 1 Page 1/8 Climate: The prevailing climate in the Maltese Islands is typically Mediterranean, with a mild, wet winter and a long, dry summer. -

Winter Escapes

Winter Escapes 22 unmissable travel adventures departing November 2020 – January 2021 10 superb new winter destinations, including St Petersburg, Mexico & Egypt Secure your place with a low deposit of $149 T&C’s apply BETTER WEATHER? QUIETER SITES? AVOIDING THE CHRISTMAS CHORES? There are many reasons to choose a winter escape, but Andante Travels’ collection of Christmas and New Year tours stand out from the crowd. Embark upon an ancient world adventure to a renowned archaeological site at a time of year when tourists tend not to visit. Soak up the culture and history of a destination with many stories to tell, while markets and lights add an extra dimension to its charm. Leave grey skies behind with a far-flung exploration that takes in multiple countries from the comfort Contents of a cruise ship. Make your winter travels count and choose something different this year – the world NEW Israel, Egypt & Jordan - Cruise & Stay...pg 6 Sri Lanka. .......................................................... pg 18 is waiting and this is the perfect season to get out Israel & Palestine. ..............................................pg 7 North India ....................................................... pg 18 there and explore it. Lebanon ................................................................pg 7 Oman .................................................................. pg 19 Jackie Willis Algeria - Roman Mauretania ............................ pg 8 Chile & Easter Island. ...................................... pg 19 CEO Tunisia - The Punic