Guide to Surveying Fungi in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

<I>Hydropus Mediterraneus</I>

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2012. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/121.393 Volume 121, pp. 393–403 July–September 2012 Laccariopsis, a new genus for Hydropus mediterraneus (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) Alfredo Vizzini*, Enrico Ercole & Samuele Voyron Dipartimento di Scienze della Vita e Biologia dei Sistemi - Università degli Studi di Torino, Viale Mattioli 25, I-10125, Torino, Italy *Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract — Laccariopsis (Agaricales) is a new monotypic genus established for Hydropus mediterraneus, an arenicolous species earlier often placed in Flammulina, Oudemansiella, or Xerula. Laccariopsis is morphologically close to these genera but distinguished by a unique combination of features: a Laccaria-like habit (distant, thick, subdecurrent lamellae), viscid pileus and upper stipe, glabrous stipe with a long pseudorhiza connecting with Ammophila and Juniperus roots and incorporating plant debris and sand particles, pileipellis consisting of a loose ixohymeniderm with slender pileocystidia, large and thin- to thick-walled spores and basidia, thin- to slightly thick-walled hymenial cystidia and caulocystidia, and monomitic stipe tissue. Phylogenetic analyses based on a combined ITS-LSU sequence dataset place Laccariopsis close to Gloiocephala and Rhizomarasmius. Key words — Agaricomycetes, Physalacriaceae, /gloiocephala clade, phylogeny, taxonomy Introduction Hydropus mediterraneus was originally described by Pacioni & Lalli (1985) based on collections from Mediterranean dune ecosystems in Central Italy, Sardinia, and Tunisia. Previous collections were misidentified as Laccaria maritima (Theodor.) Singer ex Huhtinen (Dal Savio 1984) due to their laccarioid habit. The generic attribution to Hydropus Kühner ex Singer by Pacioni & Lalli (1985) was due mainly to the presence of reddish watery droplets on young lamellae and sarcodimitic tissue in the stipe (Corner 1966, Singer 1982). -

Checklist of Argentine Agaricales 4

Checklist of the Argentine Agaricales 4. Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae 1 2* N. NIVEIRO & E. ALBERTÓ 1Instituto de Botánica del Nordeste (UNNE-CONICET). Sargento Cabral 2131, CC 209 Corrientes Capital, CP 3400, Argentina 2Instituto de Investigaciones Biotecnológicas (UNSAM-CONICET) Intendente Marino Km 8.200, Chascomús, Buenos Aires, CP 7130, Argentina CORRESPONDENCE TO *: [email protected] ABSTRACT— A species checklist of 86 genera and 709 species belonging to the families Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae occurring in Argentina, and including all the species previously published up to year 2011 is presented. KEY WORDS—Agaricomycetes, Marasmius, Mycena, Collybia, Clitocybe Introduction The aim of the Checklist of the Argentinean Agaricales is to establish a baseline of knowledge on the diversity of mushrooms species described in the literature from Argentina up to 2011. The families Amanitaceae, Pluteaceae, Hygrophoraceae, Coprinaceae, Strophariaceae, Bolbitaceae and Crepidotaceae were previoulsy compiled (Niveiro & Albertó 2012a-c). In this contribution, the families Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae are presented. Materials & Methods Nomenclature and classification systems This checklist compiled data from the available literature on Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae recorded for Argentina up to the year 2011. Nomenclature and classification systems followed Singer (1986) for families. The genera Pleurotus, Panus, Lentinus, and Schyzophyllum are included in the family Polyporaceae. The Tribe Polyporae (including the genera Polyporus, Pseudofavolus, and Mycobonia) is excluded. There were important rearrangements in the families Tricholomataceae and Polyporaceae according to Singer (1986) over time to present. Tricholomataceae was distributed in six families: Tricholomataceae, Marasmiaceae, Physalacriaceae, Lyophyllaceae, Mycenaceae, and Hydnaginaceae. Some genera belonging to this family were transferred to other orders, i.e. Rickenella (Rickenellaceae, Hymenochaetales), and Lentinellus (Auriscalpiaceae, Russulales). -

Jamur Polyporales Di Twa Suranadi Lombok Barat

Biopendix, Volume 7, Nomor 1, Desember 2020, hlm. 49-53 JAMUR POLYPORALES DI TWA SURANADI LOMBOK BARAT Meilinda Pahriana Sulastri*1, Hasan Basri2 Program Studi Biologi, Universitas Islam Al-Azhar, Mataram, NTB Coresponding author: Meilinda Pahriana Sulastri; Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Mushrooms are a member of the kingdom of fungi, which has a high level of diversity in Indonesia. In general, fungi will grow in humid environmental conditions, especially during the rainy season on weathered wood, litter and trees. Macro fungi are fungi that form fruiting bodies and can be observed without using a microscope. Macro fungi generally consist of members of the Ascomycota and Basidomycota groups. This study aims to determine which mushrooms are included in the Polyporales order that grows in TWA Suranadi Methods: This research is descriptive exploratory by exploring and describing the macrophages found in TWA Suranadi. Sampling was carried out by the cruise method (Cruise Method). Identification is done by matching observational data in the form of morphological characteristics and environmental conditions using reference books and various scientific journals on macrofungal species. Results: The results showed that there were 7 species from 2 fungal families of the Polyporales order, namely: Trametes sp., Microporus sp. 1, Microporus sp. 2, Polyporus sp. 1, Polyporus sp. 2, Datronia sp. and Ganoderma sp. Conclusion: Based on the identification results, 2 families and 8 species were found belonging to the Polyporales order in TWA Suranadi, namely Trametes sp., Microporus sp. 1, Microporus sp. 2, Polyporus sp. 1, Polyporus sp. 2, Datronia sp., and Ganoderma sp. Keywords: fungi, Polyporales, TWA Suranadi Abstrak Latar Belakang: Jamur termasuk dalam anggota kingdom fungi yang memiliki tingkat keanekaragaman tinggi di Indonesia. -

Phylogenetic Classification of Trametes

TAXON 60 (6) • December 2011: 1567–1583 Justo & Hibbett • Phylogenetic classification of Trametes SYSTEMATICS AND PHYLOGENY Phylogenetic classification of Trametes (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) based on a five-marker dataset Alfredo Justo & David S. Hibbett Clark University, Biology Department, 950 Main St., Worcester, Massachusetts 01610, U.S.A. Author for correspondence: Alfredo Justo, [email protected] Abstract: The phylogeny of Trametes and related genera was studied using molecular data from ribosomal markers (nLSU, ITS) and protein-coding genes (RPB1, RPB2, TEF1-alpha) and consequences for the taxonomy and nomenclature of this group were considered. Separate datasets with rDNA data only, single datasets for each of the protein-coding genes, and a combined five-marker dataset were analyzed. Molecular analyses recover a strongly supported trametoid clade that includes most of Trametes species (including the type T. suaveolens, the T. versicolor group, and mainly tropical species such as T. maxima and T. cubensis) together with species of Lenzites and Pycnoporus and Coriolopsis polyzona. Our data confirm the positions of Trametes cervina (= Trametopsis cervina) in the phlebioid clade and of Trametes trogii (= Coriolopsis trogii) outside the trametoid clade, closely related to Coriolopsis gallica. The genus Coriolopsis, as currently defined, is polyphyletic, with the type species as part of the trametoid clade and at least two additional lineages occurring in the core polyporoid clade. In view of these results the use of a single generic name (Trametes) for the trametoid clade is considered to be the best taxonomic and nomenclatural option as the morphological concept of Trametes would remain almost unchanged, few new nomenclatural combinations would be necessary, and the classification of additional species (i.e., not yet described and/or sampled for mo- lecular data) in Trametes based on morphological characters alone will still be possible. -

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella Species

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Printed in Eko-trykk A/S, Førde, Norway Printing date: 1. August 1995 ISBN 82-90724-14-4 ISSN 0802-4966 A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway 6 Authors address: Center for Forest Mycology Research Forest Products Laboratory United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service One Gifford Pinchot Dr. Madison, WI 53705 USA ABSTRACT Once a taxonomic refugium for nearly any white-spored agaric with an annulus and attached gills, the concept of the genus Armillaria has been clarified with the neotypification of Armillaria mellea (Vahl:Fr.) Kummer and its acceptance as type species of Armillaria (Fr.:Fr.) Staude. Due to recognition of different type species over the years and an extremely variable generic concept, at least 274 species and varieties have been placed in Armillaria (or in Armillariella Karst., its obligate synonym). Only about forty species belong in the genus Armillaria sensu stricto, while the rest can be placed in forty-three other modem genera. This study is based on original descriptions in the literature, as well as studies of type specimens and generic and species concepts by other authors. This publication consists of an alphabetical listing of all epithets used in Armillaria or Armillariella, with their basionyms, currently accepted names, and other obligate and facultative synonyms. -

Preliminary Classification of Leotiomycetes

Mycosphere 10(1): 310–489 (2019) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/7 Preliminary classification of Leotiomycetes Ekanayaka AH1,2, Hyde KD1,2, Gentekaki E2,3, McKenzie EHC4, Zhao Q1,*, Bulgakov TS5, Camporesi E6,7 1Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650201, Yunnan, China 2Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand 3School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand 4Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand 5Russian Research Institute of Floriculture and Subtropical Crops, 2/28 Yana Fabritsiusa Street, Sochi 354002, Krasnodar region, Russia 6A.M.B. Gruppo Micologico Forlivese “Antonio Cicognani”, Via Roma 18, Forlì, Italy. 7A.M.B. Circolo Micologico “Giovanni Carini”, C.P. 314 Brescia, Italy. Ekanayaka AH, Hyde KD, Gentekaki E, McKenzie EHC, Zhao Q, Bulgakov TS, Camporesi E 2019 – Preliminary classification of Leotiomycetes. Mycosphere 10(1), 310–489, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/7 Abstract Leotiomycetes is regarded as the inoperculate class of discomycetes within the phylum Ascomycota. Taxa are mainly characterized by asci with a simple pore blueing in Melzer’s reagent, although some taxa have lost this character. The monophyly of this class has been verified in several recent molecular studies. However, circumscription of the orders, families and generic level delimitation are still unsettled. This paper provides a modified backbone tree for the class Leotiomycetes based on phylogenetic analysis of combined ITS, LSU, SSU, TEF, and RPB2 loci. In the phylogenetic analysis, Leotiomycetes separates into 19 clades, which can be recognized as orders and order-level clades. -

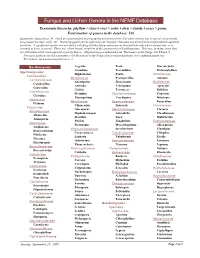

9B Taxonomy to Genus

Fungus and Lichen Genera in the NEMF Database Taxonomic hierarchy: phyllum > class (-etes) > order (-ales) > family (-ceae) > genus. Total number of genera in the database: 526 Anamorphic fungi (see p. 4), which are disseminated by propagules not formed from cells where meiosis has occurred, are presently not grouped by class, order, etc. Most propagules can be referred to as "conidia," but some are derived from unspecialized vegetative mycelium. A significant number are correlated with fungal states that produce spores derived from cells where meiosis has, or is assumed to have, occurred. These are, where known, members of the ascomycetes or basidiomycetes. However, in many cases, they are still undescribed, unrecognized or poorly known. (Explanation paraphrased from "Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edition.") Principal authority for this taxonomy is the Dictionary of the Fungi and its online database, www.indexfungorum.org. For lichens, see Lecanoromycetes on p. 3. Basidiomycota Aegerita Poria Macrolepiota Grandinia Poronidulus Melanophyllum Agaricomycetes Hyphoderma Postia Amanitaceae Cantharellales Meripilaceae Pycnoporellus Amanita Cantharellaceae Abortiporus Skeletocutis Bolbitiaceae Cantharellus Antrodia Trichaptum Agrocybe Craterellus Grifola Tyromyces Bolbitius Clavulinaceae Meripilus Sistotremataceae Conocybe Clavulina Physisporinus Trechispora Hebeloma Hydnaceae Meruliaceae Sparassidaceae Panaeolina Hydnum Climacodon Sparassis Clavariaceae Polyporales Gloeoporus Steccherinaceae Clavaria Albatrellaceae Hyphodermopsis Antrodiella -

Kings Park and Botanic Garden Fungi

_________________________________________________________________________ KINGS PARK FUNGI [Version 1.1] A VISUAL GUIDE TO SPECIES RECORDED IN SURVEYS 2009 – 2012 Neale L. Bougher Department of Parks and Wildlife, Western Australian Herbarium [email protected] This Visual Guide is a work-in-progress. It may be printed for own use but is not to be distributed or copied (except to your personal computer devices) without consent from the author, nor scientifically referenced. _________________________________________________________________________ © N.L. Bougher (2015) Kings Park Fungi [Version 1.1] Page 1 of 88 KINGS PARK FUNGI [Version 1.1] A VISUAL GUIDE TO SPECIES RECORDED IN SURVEYS 2009 – 2012 Note from the Author - Neale L. Bougher, June 2015 I would welcome any comments, corrections, images etc… as this Visual Guide is a Acknowledgements work-in-progress primarily compiled to assist and encourage (a) myself and other To all of the 35 people (mainly volunteers) participants of ongoing fungi surveys at Kings Park, (b) preparation of my intended who have participated in survey days at book - Fungi of Kings Park and Bold Park, and (c) expansion of the 2009 edition of my Kings Park since 2009 and have helped to book - Fungi of the Perth Region and Beyond (available at www.fungiperth.org.au). describe and identify the fungi. Many of the 261 fungi in this Visual Guide are poorly studied and therefore tentatively identified or unidentified. In subsequent versions I expect that some names will change, To the Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority merge with other names, or become redundant as more collections are studied. and Staff for logistically and financially I have not yet included any fungi or vouchers recorded from Kings Park before 2009. -

Fungi of the Fortuna Forest Reserve: Taxonomy and Ecology with Emphasis on Ectomycorrhizal Communities

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.16.045724; this version posted April 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Fungi of the Fortuna Forest Reserve: Taxonomy and ecology with emphasis on ectomycorrhizal communities Adriana Corrales1 and Clark L. Ovrebo2 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Universidad del Rosario. Bogota, 111221, Colombia. 2 Department of Biology, University of Central Oklahoma. Edmond, OK. USA. ABSTRACT Panamanian montane forests harbor a high diversity of fungi, particularly of ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi, however their taxonomy and diversity patterns remain for the most part unexplored. Here we present state of the art fungal taxonomy and diversity patterns at Fortuna Forest Reserve based on morphological and molecular identification of over 1,000 fruiting body collections of macromycetes made over a period of five years. We compare these new results with previously published work based on environmental sampling of Oreomunnea mexicana root tips. We compiled a preliminary list of species and report 22 new genera and 29 new fungal species for Panama. Based on fruiting body collection data we compare the species composition of ECM fungal communities associated with Oreomunnea stands across sites differing in soil fertility and amount of rainfall. We also examine the effect of a long-term nitrogen addition treatment on the fruiting body production of ECM fungi. Finally, we discuss the biogeographic importance of Panama collections which fill in the knowledge gap of ECM fungal records between Costa Rica and Colombia. -

Anti-Staphylococcal and Antioxidant Properties of Crude Ethanolic Extracts of Macrofungi Collected from the Philippines

Pharmacogn J. 2018; 10(1):106-109 A Multifaceted Journal in the field of Natural Products and Pharmacognosy Original Article www.phcogj.com | www.journalonweb.com/pj | www.phcog.net Anti-Staphylococcal and Antioxidant Properties of Crude Ethanolic Extracts of Macrofungi Collected from the Philippines Christine May Gaylan1, John Carlo Estebal1, Ourlad Alzeus G. Tantengco2, Elena M. Ragragio1 ABSTRACT Introduction: Macrofungi have been used in the Philippines as source of food and traditional medicines. However, these macrofungi in the Philippines have not yet been studied for different biological activities. Thus, this research determined the potential antibacterial and antioxidant activities of crude ethanolic extracts of seven macrofungi collected in Bataan, Philippines. Methods: Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion assay and broth microdilution method were used to screen for the antibacterial activity and DPPH scavenging assay for the determination of antioxidant activity. Results: F. rosea, G. applanatum, G. lucidum and P. pinisitus exhibited zones of inhibition ranging from 6.55 ± 0.23 mm to 7.43 ± 0.29 mm against S. aureus, D. confragosa, F. rosea, G. lucidum, M. xanthopus and P. pinisitus showed antimicrobial activities against S. aureus with an MIC50 ranging from 1250 μg/mL to 10000 μg/mL. F. rosea, G. applanatum, G. lucidum, M. xanthopus exhibited excellent antioxidant activity with F. rosea having the highest antioxidant activity among all the extracts tested (3.0 μg/mL). Conclusion: Based on the results, these Philippine macrofungi showed antistaphylococcal activity independent of 1 Christine May Gaylan , the antioxidant activity. These can be further studied as potential sources of antibacterial and John Carlo Estebal1, antioxidant compounds. -

A Higher-Level Phylogenetic Classification of the Fungi

mycological research 111 (2007) 509–547 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mycres A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi David S. HIBBETTa,*, Manfred BINDERa, Joseph F. BISCHOFFb, Meredith BLACKWELLc, Paul F. CANNONd, Ove E. ERIKSSONe, Sabine HUHNDORFf, Timothy JAMESg, Paul M. KIRKd, Robert LU¨ CKINGf, H. THORSTEN LUMBSCHf, Franc¸ois LUTZONIg, P. Brandon MATHENYa, David J. MCLAUGHLINh, Martha J. POWELLi, Scott REDHEAD j, Conrad L. SCHOCHk, Joseph W. SPATAFORAk, Joost A. STALPERSl, Rytas VILGALYSg, M. Catherine AIMEm, Andre´ APTROOTn, Robert BAUERo, Dominik BEGEROWp, Gerald L. BENNYq, Lisa A. CASTLEBURYm, Pedro W. CROUSl, Yu-Cheng DAIr, Walter GAMSl, David M. GEISERs, Gareth W. GRIFFITHt,Ce´cile GUEIDANg, David L. HAWKSWORTHu, Geir HESTMARKv, Kentaro HOSAKAw, Richard A. HUMBERx, Kevin D. HYDEy, Joseph E. IRONSIDEt, Urmas KO˜ LJALGz, Cletus P. KURTZMANaa, Karl-Henrik LARSSONab, Robert LICHTWARDTac, Joyce LONGCOREad, Jolanta MIA˛ DLIKOWSKAg, Andrew MILLERae, Jean-Marc MONCALVOaf, Sharon MOZLEY-STANDRIDGEag, Franz OBERWINKLERo, Erast PARMASTOah, Vale´rie REEBg, Jack D. ROGERSai, Claude ROUXaj, Leif RYVARDENak, Jose´ Paulo SAMPAIOal, Arthur SCHU¨ ßLERam, Junta SUGIYAMAan, R. Greg THORNao, Leif TIBELLap, Wendy A. UNTEREINERaq, Christopher WALKERar, Zheng WANGa, Alex WEIRas, Michael WEISSo, Merlin M. WHITEat, Katarina WINKAe, Yi-Jian YAOau, Ning ZHANGav aBiology Department, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610, USA bNational Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, -

2 the Numbers Behind Mushroom Biodiversity

15 2 The Numbers Behind Mushroom Biodiversity Anabela Martins Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, School of Agriculture (IPB-ESA), Portugal 2.1 Origin and Diversity of Fungi Fungi are difficult to preserve and fossilize and due to the poor preservation of most fungal structures, it has been difficult to interpret the fossil record of fungi. Hyphae, the vegetative bodies of fungi, bear few distinctive morphological characteristicss, and organisms as diverse as cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algal groups, and oomycetes can easily be mistaken for them (Taylor & Taylor 1993). Fossils provide minimum ages for divergences and genetic lineages can be much older than even the oldest fossil representative found. According to Berbee and Taylor (2010), molecular clocks (conversion of molecular changes into geological time) calibrated by fossils are the only available tools to estimate timing of evolutionary events in fossil‐poor groups, such as fungi. The arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiotic fungi from the division Glomeromycota, gen- erally accepted as the phylogenetic sister clade to the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, have left the most ancient fossils in the Rhynie Chert of Aberdeenshire in the north of Scotland (400 million years old). The Glomeromycota and several other fungi have been found associated with the preserved tissues of early vascular plants (Taylor et al. 2004a). Fossil spores from these shallow marine sediments from the Ordovician that closely resemble Glomeromycota spores and finely branched hyphae arbuscules within plant cells were clearly preserved in cells of stems of a 400 Ma primitive land plant, Aglaophyton, from Rhynie chert 455–460 Ma in age (Redecker et al. 2000; Remy et al. 1994) and from roots from the Triassic (250–199 Ma) (Berbee & Taylor 2010; Stubblefield et al.