Rosh Hashanah- Yom Kippur 5778

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rabbi Eliezer Levin, ?"YT: Mussar Personified RABBI YOSEF C

il1lj:' .N1'lN1N1' invites you to join us in paying tribute to the memory of ,,,.. SAMUEL AND RENEE REICHMANN n·y Through their renowned benevolence and generosity they have nobly benefited the Torah community at large and have strengthened and sustained Yeshiva Yesodei Hatorah here in Toronto. Their legendary accomplishments have earned the respect and gratitude of all those whose lives they have touched. Special Honorees Rabbi Menachem Adler Mr. & Mrs. Menachem Wagner AVODASHAKODfSHAWARD MESORES A VOS AW ARD RESERVE YOUR AD IN OUR TRIBUTE DINNER JOURNAL Tribute Dinner to be held June 3, 1992 Diamond Page $50,000 Platinum Page $36, 000 Gold Page $25,000 Silver Page $18,000 Bronze Page $10,000 Parchment $ 5,000 Tribute Page $3,600 Half Page $500 Memoriam Page '$2,500 Quarter Page $250 Chai Page $1,800 Greeting $180 Full Page $1,000 Advertising Deadline is May 1. 1992 Mall or fax ad copy to: REICHMANN ENDOWMENT FUND FOR YYH 77 Glen Rush Boulevard, Toronto, Ontario M5N 2T8 (416) 787-1101 or Fax (416) 787-9044 GRATITUDE TO THE PAST + CONFIDENCE IN THE FUTURE THEIEWISH ()BSERVER THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021 -6615 is published monthly except July and August by theAgudath Israel of America, 84 William Street, New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage paid in New York, N.Y. LESSONS IN AN ERA OF RAPID CHANGE Subscription $22.00 per year; two years, $36.00; three years, $48.00. Outside of the United States (US funds drawn on a US bank only) $1 O.00 6 surcharge per year. -

Korach 5776 July 8, 2016

Korach 5776 July 8, 2016 A Taste of Torah Stories For The Soul It’s All About Me By Rabbi Mordechai Fleisher A Friendly Argument In today’s world, it’s very important for You know the rest of the story. 250 Jews During the late 1800’s, there a politician to convince everyone that he bring pans with incense, and a Divine was a sharp debate between or she is working for the benefit of the fire consumes them. Korach and his people. More often than not, that claim is two sidekicks, Dasan and Aviram, are several prominent Torah leaders laughable. To that end, our Sages (Pirkei swallowed, along with their families and regarding a particular issue. The Avos 2:3) tell us to be wary of goverment possessions, by the earth. disagreement was quite heated, officials, for they may seem very friendly Why were two different punishments each side strongly advocating its when they stand to gain from the necessary? To make this question even position as the correct approach. relationship, but they will abandon you more perplexing, the Talmud (Sanhedrin when you are no longer useful. Two of the leading Torah 110a) records an opinion that Korach authorities of the time, Rabbi About fifteen years ago, when I was himself suffered both forms of retribution: studying in yeshiva in Eretz Yisrael, I was Not only was he swallowed, he was also Chaim Soloveitchik (1853-1918) a guest at a Shabbos meal along with a burned by the Divine fire. What is the and Rabbi Meir Simcha of Dvinsk British chap who was looking to convert significance of his being subjected to both (1843-1926) were at the forefront to Judaism. -

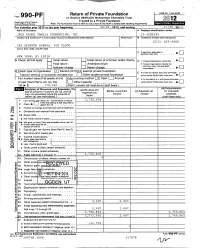

Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545 -0052 Fonn 990 -PFI or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Sennce Note The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning 12/01 , 2012 , and endii 11/30. 2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMT FAMILY FOUNDATION. INC. 13-3202295 Number and street ( or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) (212) 629-9600 463 SEVENTH AVENUE, 4TH FLOOR City or town, state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is , q pending , check here . NEW YORK, NY 10018 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organ izations . check here El Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address change Name chang e computation . • • • • • • . H Check type of organization X Section 501 ( cJ 3 exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation under section 507(bxlXA ), check here . Ill. El I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accountin g method X Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col. (c), line 0 Other ( specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ under section 507(b )( 1)(B), check here 16) 10- $ 17 0 , 2 4 0 . -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

The Jewish Observer

··~1 .··· ."SH El ROT LEUMI''-/ · .·_ . .. · / ..· .:..· 'fo "ABSORPTION" •. · . > . .· .. ·· . NATIONALSERVICE ~ ~. · OF SOVIET. · ••.· . ))%, .. .. .. · . FOR WOMEN . < ::_:··_---~ ...... · :~ ;,·:···~ i/:.)\\.·:: .· SECOND LOOKS: · · THE BATil.E · . >) .·: UNAUTHORIZED · ·· ·~·· "- .. OVER CONTROL AUTOPSIES · · · OF THE RABBlNATE . THE JEWISH OBSERVER in this issue ... DISPLACED GLORY, Nissan Wo/pin ............................................................ 3 "'rELL ME, RABBI BUTRASHVILLI .. ,"Dov Goldstein, trans lation by Mirian1 Margoshes 5 So~rn THOUGHTS FROM THE ROSHEI YESHIVA 8 THE RABBINATE AT BAY, David Meyers................................................ 10 VOLUNTARY SERVICE FOR WOMEN: COMPROMISE OF A NATION'S PURITY, Ezriel Toshavi ..... 19 SECOND LOOKS RESIGNATION REQUESTED ............................................................... 25 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and August, by the Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, New York 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription: $5.00 per year; Two years, $8.50; Three years, $12.00; outside of the United States, $6.00 per year. Single copy, fifty cents. SPECIAL OFFER! Printed in the U.S.A. RABBI N ISSON W OLPJN THE JEWISH OBSERVER Editor 5 Beekman Street 7 New York, N. Y. 10038 Editorial Board D NEW SUBSCRIPTION: $5 - 1 year of J.O. DR. ERNEST L. BODENHEIMER Plus $3 • GaHery of Portraits of Gedolei Yisroel: FREE! Chairman RABBI NATHAN BULMAN D RENEWAL: $12 for 3 years of J.0. RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Plus $3 - Gallery of Portraits of Gedo lei Yisroel: FREE! JOSEPH FRIEDENSON D GIFT: $5 - 1 year; $8.50, 2 yrs.; $12, 3 yrs. of ].0. RABBI YAACOV JACOBS Plus $3 ·Gallery of Portraits of Gedolei Yisroel: FREE! RABBI MOSHE SHERER Send '/Jf agazine to: Send Portraits to: THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not iVarne .... -

Motzoei Shabbos at the Agudath Israel Convention 2015

Motzoei Shabbos at the Agudath Israel Convention 2015 November 15, 2015 Following a beautiful, uplifting Shabbos, Motzoei Shabbos at the 93rd annual Agudath Israel of America convention combined inspiration and the tackling of difficult communal issues, under the banner of the convention’s theme of “Leadership.” Keynote Session At 8:30 pm, the main hotel ballroom was once again full, for the Motzoei Shabbos Keynote Session. In addition to the overflow crowd in the Convention Hotel itself, many additional thousands followed the session electronically.The dais featured leading gedolim of our generation, including two special guests from Eretz Yisroel, HaRav Dov Yaffe, Mashgiach in Yeshiva Knesses Chizkiyahu; and the Sadigura Rebbe. Convention Chairman Binyomin Berger spoke about Agudath Israel of America’s leadership on behalf of the needs of every individual in klal Yisroel, from cradle to grave. He praised the strong representation of young individuals at the convention, who are willing to roll up their sleeves on behalf of our community. “None of us are smarter than all us,” he exclaimed. The Novominsker Rebbe, Rosh Agudas Yisroel and member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of America, was in Eretz Yisroel for a family simcha. The Rebbe delivered a special video message to the convention, highlighting both the physical and spiritual dangers our community faces, and once again stressed the dangers of the burgeoning “Open Orthodoxy” movement. “These are the chevlai moshiach,” the Rebbe exclaimed. “We must think and breathe emunah; think and breathe ahavas Torah and yiras shamayim; and think and breathe tzedaka v’chessed.” Shabbos was the yartzeit of HaRav Aharon Kotler zt”l, legendary Rosh Yeshiva of Bais Medrash Govoha of Lakewood. -

JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX

NISSAN 5768 / APRIL 2008, VOL. 13 Green and Clean JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX NISSAN 5768 / APRIL 2008, VOL. 13 Green and Clean JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX COMMENTARY JERUSALEM COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY PRESIDENT Shalom! opportunity to receive an excellent education Prof. Joseph S. Bodenheimer allowing them to become highly-skilled, ROSH HAYESHIVA Rabbi Z. N. Goldberg Of the many things sought after professionals. More important ROSH BEIT HAMIDRASH we are proud at JCT, for our students is the opportunity available Rabbi Natan Bar Chaim nothing is more RECTOR at the College to receive an education Prof. Joseph M. Steiner prized than our focusing on Jewish values. It is this DIRECTOR-GENERAL students. In every education towards values that has always Dr. Shimon Weiss VICE PRESIDENT FOR DEVELOPMENT issue of “Perspective” been the hallmark of JCT and it is this AND EXTERNAL AFFAIRS we profile one of our students as a way of commitment to Jewish ethical values that Reuven Surkis showing who they are and of sharing their forms the foundation from which Israeli accomplishments with you. society will grow and flourish - and our EDITORS Our student body of 2,500 is a students and graduates take pride in being Rosalind Elbaum, Debbie Ross, Penina Pfeuffer microcosm of Israeli society: 21% are Olim committed to this process. DESIGN & PRODUCTION (immigrants) from the former Soviet Union, As we approach the Pesach holiday, the Studio Fisher Ethiopia, South America, North America, 60th anniversary of the State of Israel and JCT Perspective invites the submission of arti- Europe, Australia and South Africa, whilst the 40th anniversary of JCT, let us reaffirm cles and press releases from the public. -

The Rabbi Naftali Riff Yeshiva

AHHlVERSARtJ TOGtTHtR! All new orden will receive a Z0°/o Discount! Minimum Order of $10,000 required. 35% deposit required. (Ofter ends February 28, 2003) >;! - . ~S~i .. I I" o i )• ' Shevat 5763 •January 2003 U.S.A.$3.50/Foreign $4.50 ·VOL XXXVI/NO. I THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021-6615 is published monthly except July and August by the Agudath Israel of America, 42 Broadway, New York, NY10004. Periodicals postage paid in New York, NY. Subscription $24.00 per year; two years, $44.00; three years, $60.00. Outside ol the United States (US funds drawn on a US bank only) $12.00 surcharge per year. Single copy $3.50; foreign $4.50. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to; The Jewish Observer, 42 a.roadway, NY. NY.10004. Tel:212-797-9000, Fax: 646-254-1600. Printed in the U.S.A. KIRUV TODAY IN THE USA RABBI NISSON WOLPIN, EDITOR EDITORIAL BOARD 4 Kiruv Today: Now or Never, Rabbi Yitzchok Lowenbraun RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Chairman RABBI ABBA BRUONY 10 The Mashgiach Comes To Dallas, Kenneth Chaim Broodo JOSEPH FRIEOENSON RABBI YISROEL MEIR KIRZNER RABBI NOSSON SCHERMAN 16 How Many Orthodox Jews Can There Be? PROF. AARON TWEASKI Chanan (Anthony) Gordon and Richard M. Horowitz OR. ERNST L BODENHEIMER Z"l RABBI MOSHE SHERER Z"L Founders 30 The Lonely Man of Kiruv, by Chaim Wolfson MANAGEMENT BOARD AVI FISHOF, NAFTOLI HIRSCH ISAAC KIRZNER, RABBI SHLOMO LESIN NACHUM STEIN ERETZ YISROEL: SHARING THE PAIN RABBI YOSEF C. GOLDING Managing Editor Published by 18 Breaking Down the Walls, Mrs. -

2015 Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS I As Filed Data - I DLN: 93491315003346 OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2015 Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service ► ► Information about Form 990- PF and its instructions is at www. irs.gov /form99Opf . • • ' For calendar year 2015 , or tax year beginning 01-01 - 2015 , and ending 12-31-2015 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE EDDIE AND RACHELLE BETESH FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 13-3981963 EDDIE BETESH Number and street ( or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) BTelephone number (see instructions) C/O SARAMAX-1372 BROADWAY-FL 7 (212) 481-8550 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ► NEW YORK, NY 10018 P G Check all that apply [Initial return [Initial return former public charity of a D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► F-Final return F-A mended return P F-Address change F-Name change 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach computation ► E If private foundation status was terminated H Check type of organization [Section 501( c)(3) exempt private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► F Section 4947( a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation IFair market value of all assets at end ] Accounting method [Cash F-Accrual F If the foundation -

VAYIGASH.Qxp Layout 1 17/12/2019 14:53 Page 1

Vol.32 No.15 VAYIGASH.qxp_Layout 1 17/12/2019 14:53 Page 1 4 January 2020 7 Tevet 5780 Shabbat ends London 4.59pm Jerusalem 5.28pm Volume 32 No. 15 Vayigash Artscroll p.250 | Haftarah p.1144 Hertz p.169 | Haftarah p.178 Soncino p.277 | Haftarah p.293 The Fast of 10 Tevet is on Tuesday, starting in London at 6.16am and ending at 4.56pm In loving memory of Devorah Bat Avraham "Now there was no bread in all the earth for the famine was very severe; the land of Egypt and the land of Canaan became weary from hunger" (Bereishit 47:13). 1 Vol.32 No.15 VAYIGASH.qxp_Layout 1 17/12/2019 14:53 Page 2 Sidrah Summary: Vayigash 1st Aliya (Kohen) – Bereishit 44:18-30 Question: What money and provisions did Yosef 22 years after Yosef was sold by his brothers, they give to Binyamin for the journey? (45:22) Answer now face the prospect of their father Yaakov on bottom of page 6. ‘losing’ another one of his sons, Binyamin. Yehuda does not yet know that the viceroy of Egypt 5th Aliya (Chamishi) – 45:28-46:27 standing in front of him is actually Yosef. He Yaakov travels to Egypt, stopping at Beersheva to approaches Yosef, recounting Yosef’s demand to bring an offering. God appears to Yaakov in a see Binyamin and Yaakov’s reluctance to let night vision, allaying his fears of leaving Cana’an Binyamin leave. Having already ‘lost’ Rachel’s to go to Egypt, and promising to make his other son (Yosef), Yaakov did not want disaster to progeny into a great nation. -

Holiness-A Human Endeavor

Isaac Selter Holiness: A Human Endeavor “The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the whole Israelite community and say to them: You shall be holy, for I, the Lord your God, am holy1.” Such a verse is subject to different interpretations. On the one hand, God is holy, and through His election of the People of Israel and their acceptance of the yoke of heaven at Mount Sinai, the nation attains holiness as well. As Menachem Kellner puts it, “the imposition of the commandments has made Israel intrinsically holy2.” Israel attains holiness because God is holy. On the other hand, the verse could be seen as introducing a challenge to the nation to achieve such a holiness. The verse is not ascribing an objective metaphysical quality inherent in the nation of Israel. Which of these options is real holiness? The notion that sanctity is an objective metaphysical quality inherent in an item or an act is one championed by many Rishonim, specifically with regard to to the sanctity of the Land of Israel. God promises the Children of Israel that sexual morality will cause the nation to be exiled from its land. Nachmanides explains that the Land of Israel is more sensitive than other lands with regard to sins due to its inherent, metaphysical qualities. He states, “The Honorable God created everything and placed the power over the ones below in the ones above and placed over each and every people in their lands according to their nations a star and a specific constellation . but upon the land of Israel - the center of the [world's] habitation, the inheritance of God [that is] unique to His name - He did not place a captain, officer or ruler from the angels, in His giving it as an 1 Leviticus 19:1-2 2 Maimonidies' Confrontation with Mysticism, Menachem Kellner, pg 90 inheritance to his nation that unifies His name - the seed of His beloved one3”. -

Vertientes Del Judaismo #3

CLASES DE JUDAISMO VERTIENTES DEL JUDAISMO #3 Por: Eliyahu BaYonah Director Shalom Haverim Org New York Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • La Ortodoxia moderna comprende un espectro bastante amplio de movimientos, cada extracción toma varias filosofías aunque relacionados distintamente, que en alguna combinación han proporcionado la base para todas las variaciones del movimiento de hoy en día. • En general, la ortodoxia moderna sostiene que la ley judía es normativa y vinculante, y concede al mismo tiempo un valor positivo para la interacción con la sociedad contemporánea. Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • En este punto de vista, el judaísmo ortodoxo puede "ser enriquecido" por su intersección con la modernidad. • Además, "la sociedad moderna crea oportunidades para ser ciudadanos productivos que participan en la obra divina de la transformación del mundo en beneficio de la humanidad". • Al mismo tiempo, con el fin de preservar la integridad de la Halajá, cualquier área de “fuerte inconsistencia y conflicto" entre la Torá y la cultura moderna debe ser evitada. La ortodoxia moderna, además, asigna un papel central al "Pueblo de Israel " Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • La ortodoxia moderna, como una corriente del judaísmo ortodoxo representado por instituciones como el Consejo Nacional para la Juventud Israel, en Estados Unidos, es pro-sionista y por lo tanto da un estatus nacional, así como religioso, de mucha importancia en el Estado de Israel, y sus afiliados que son, por lo general, sionistas en la orientación. • También practica la implicación con Judíos no ortodoxos que se extiende más allá de "extensión (kiruv)" a las relaciones institucionales y la cooperación continua, visto como Torá Umaddá.