May-June 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May-June 2010

NON-PROFITNON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION U.S.U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE paipaiD D TheThe e emilymily Dickinson Dickinson i ninTTernaernaTTionalional s socieocieTTyy CHICAGO,CHICAGO, IL IL PERMITPERMIT NO. NO. 2422 2422 The emily Dickinson inTernaTional socieTy EDISEDIS Bulletin Bulletin c/oc/oc/o akaaka aka associates,associates, associates, inc.inc. inc. 645645 N. N.Michigan Michigan Avenue Avenue SuiteSuite 800 800 Chicago,Chicago, IL IL 60611 60611 eeeeeDDDDDisisisisis 20092009 200920092009 aa aaannualnnualnnualnnualnnual mm mmmeeeeeeeeeeTTTTTinginginginging eeDDisiseee ee2010D DD2010DDisisisisis 2010 2010 20102010i 2010ninTTernaerna aa aaannualnnualnnualnnualnnualTTionalional mm mm mcee eeeeceeeeonferenceonferenceTTTTTinginginginging VolumeVolume 21, 21, Number Number 2 2 November/DecemberNovember/December 2009 2009 Volume 22, Number 1 May/June 2010 “The“The“The Only Only Only News News News I knowI knowI know / Is/ / Is BulletinsIs BulletinsBulletins all allall Day DayDay / / From /From From Immortality.” Immortality.” august 6-8, 2010 EmilyEmilyEmilyEmilyEmilyEmily withwith withwith with with BeefeaterBeefeater BeefeaterBeefeater Beefeater Beefeater GuardsGuards GuardsGuards Guards Guards EllieEllieEllieEllieEllieEllie HeginbothamHeginbotham HeginbothamHeginbotham Heginbotham Heginbotham withwith withwith with with BeefeaterBeefeater BeefeaterBeefeater Beefeater Beefeater GuardsGuards GuardsGuards Guards Guards SuzanneSuzanneSuzanneSuzanneSuzanneSuzanne Juhasz,Juhasz, Juhasz,Juhasz, Juhasz, Juhasz, JonnieJonnie JonnieJonnie Jonnie -

March 2021 ACADEMIC BIOGRAPHY Lynn Keller E-Mail: Rlkeller@Wisc

March 2021 ACADEMIC BIOGRAPHY Lynn Keller E-mail: [email protected] Education: Ph.D., University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, 1981 Dissertation: Heirs of the Modernists: John Ashbery, Elizabeth Bishop, and Robert Creeley, directed by Robert von Hallberg M.A., University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, 1976 B.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, 1973 Academic Awards and Honors: Bradshaw Knight Professor of Environmental Humanities (while director of CHE, 2016-2019) Fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, 2015-2016 Martha Meier Renk Bascom Professor of Poetry, January 2003 to August 2019; emerita to present UW Institute for Research in the Humanities, Senior Fellow, Fall 1999-Spring 2004 American Association of University Women Fellowship, July 1994-June 1995 Vilas Associate, 1993-1995 (summer salary 1993, 1994) Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 1989 University nominee for NEH Summer Stipend, 1986 Fellow, University of Wisconsin Institute for Research in the Humanities, Fall semester 1983 NEH Summer Stipend, 1982 Doctoral Dissertation awarded Departmental Honors, English Department, University of Chicago, 1981 Whiting Dissertation Fellowship, 1979-80 Honorary Fellowship, University of Chicago, 1976-77 B.A. awarded “With Distinction,” Stanford University, 1973 Employment: 2016-2019 Director, Center for Culture, History and Environment, Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, UW-Madison 2014 Visiting Professor, Stockholm University, Stockholm Sweden, Spring semester 2009-2019 Faculty Associate, Center for Culture, History, and Environment, UW-Madison 1994-2019 Full Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison [Emerita after August 2019] 1987-1994 Associate Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1981-1987 Assistant Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1981 Instructor, University of Chicago Extension (course on T.S. -

Cristanne Miller SUNY Distinguished Professor of English and Edward H

Cristanne Miller SUNY Distinguished Professor of English and Edward H. Butler Professor of Literature, SUNY at Buffalo Fulbright-Tocqueville Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Université de Paris Diderot Fall 2013 Cristanne Miller is SUNY Distinguished Professor of English and Edward H. Butler Professor of Literature at the University at Buffalo. Since 2006 she has also served as the chair of the English Department at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Her research interests include comparative modernist poetry, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American poetry and the effects of the Civil War on U.S. poetry as a genre as well as gender and language issues. Professor Miller focuses mainly on Emily Dickinson, Mina Loy, Else Lasker-Schüler, Marianne Moore, Civil War poetry, and the cities of New York and Berlin between 1900 and 1930. Among her publications are Cultures of Modernism: Marianne Moore, Mina Loy, Else Lasker-Schüler. Gender and Literary Community in New York and Berlin (2005), and Marianne Moore: Questions of Authority (1995). In 1993, she co-authored, with Suzanne Juhasz and Martha Nell Smith, Comic Power in Emily Dickinson. Her book Emily Dickinson: A Poet´s Grammar (1987) received outstanding reviews. Professor Miller also co-edited, amongst others, The Emily Dickinson Handbook (1998), with Roland Hagenbüchle and Gudrun Grabher, and “Words for the Hour”: A New Anthology of American Civil War Poetry (2005) with Faith Barrett. She is currently working on Emily Dickinson’s Poems and Poetry After Gettysburg. Since 2005, Professor Miller has edited The Emily Dickinson Journal. In addition, she is a member of The Emily Dickinson International Society, The Modern Language Association, and The American Literature Association, among others. -

Emily Dickinson - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Emily Dickinson - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Emily Dickinson(10 December 1830 – 15 May 1886) Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was an American poet. Born in Amherst, Massachusetts, to a successful family with strong community ties, she lived a mostly introverted and reclusive life. After she studied at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she spent a short time at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family's house in Amherst. Thought of as an eccentric by the locals, she became known for her penchant for white clothing and her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, even leave her room. Most of her friendships were therefore carried out by correspondence. Although Dickinson was a prolific private poet, fewer than a dozen of her nearly eighteen hundred poems were published during her lifetime. The work that was published during her lifetime was usually altered significantly by the publishers to fit the conventional poetic rules of the time. Dickinson's poems are unique for the era in which she wrote; they contain short lines, typically lack titles, and often use slant rhyme as well as unconventional capitalization and punctuation. Many of her poems deal with themes of death and immortality, two recurring topics in letters to her friends. Although most of her acquaintances were probably aware of Dickinson's writing, it was not until after her death in 1886—when Lavinia, Emily's younger sister, discovered her cache of poems—that the breadth of Dickinson's work became apparent. -

Autobiographic Self-Construction in the Letters of Emily Dickinson

University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Year Autobiographic self-construction in the letters of Emily Dickinson Lori Karen Lebow University of Wollongong Lebow, Lori K, Autobiographic self-construction in the letters of Emily Dickinson, PhD thesis, Department of English, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2 NOTE This online version of the thesis may have different page formatting and pagination from the paper copy held in the University of Wollongong Library. UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG COPYRIGHT WARNING You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Autobiographic Self-Construction in the Letters of Emily Dickinson A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY From The University of Wollongong by Lori Karen Lebow, MA, Hons English Studies Program, 1999. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... A Remembrance of the Belle: Emily Dickinson on Stage A Thesis Presented by Caitlin Lee to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Dramaturgy Stony Brook University May 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Caitlin Lee We, the thesis committee for the above candidate for the Master of Fine Arts degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this thesis. Steve Marsh – Thesis Advisor Lecturer and Literary Manager, Department of Theatre Arts Maxine Kern – Second Reader Lecturer, Department of Theatre Arts This thesis is accepted by the Graduate School. Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Thesis A Remembrance of the Belle: Emily Dickinson on Stage by Caitlin Lee Master of Fine Arts in Dramaturgy Stony Brook University 2010 In September 2009, I served as the Production Dramaturg for the New York premiere production of Emily: An Amethyst Remembrance. During my research process, I learned that the true persona Emily Dickinson does fit into one particular stereotype. In this thesis I provide, I examine three different theatrical interpretations of the character of Emily Dickinson: Allison’s House by Susan Glaspell, The Belle of Amherst by William Luce, and Emily: An Amethyst Remembrance by Chris Cragin. Though each of these texts are quite different in structure, they each depict woman who is strong and loving; she is not afraid of the world, but rather it is her choice to exclude herself from it. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

The Belle of Amherst by William Luce

THE BELLE OF AMHERST BY WILLIAM LUCE DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. THE BELLE OF AMHERST Copyright © 2015, William Luce and Don Gregory All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of THE BELLE OF AMHERST is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for THE BELLE OF AMHERST are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

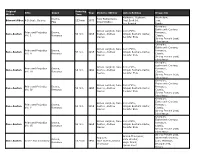

Original Writer Title Genre Running Time Year Director/Writer Actor

Original Running Title Genre Year Director/Writer Actor/Actress Keywords Writer Time Katharine Hepburn, Alcoholism, Drama, Tony Richardson; Edward Albee A Delicate Balance 133 min 1973 Paul Scofield, Loss, Play Edward Albee Lee Remick Family Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. I Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 54 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. II Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. III Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. IV Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 50 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. V Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 52 min 1995 Austen, -

UCLA FESTIVAL of PRESERVATION MARCH 3 to MARCH 27, 2011

UCLA FESTIVAL of PRESERVATION MARCH 3 to MARCH 27, 2011 i UCLA FESTIVAL of PRESERVATION MARCH 3 to MARCH 27, 2011 FESTIVAL SPONSOR Additional programming support provided, in part, by The Hollywood Foreign Press Association ii 1 FROM THE DIRECTOR As director of UCLA Film & Television Archive, it is my great pleasure to Mysel has completed several projects, including Cry Danger (1951), a introduce the 2011 UCLA Festival of Preservation. As in past years, we have recently rediscovered little gem of a noir, starring Dick Powell as an unjustly worked to put together a program that reflects the broad and deep efforts convicted ex-con trying to clear his name, opposite femme fatale Rhonda of UCLA Film & Television Archive to preserve and restore our national mov- Fleming, and featuring some great Bunker Hill locations long lost to the Los ing image heritage. Angeles wrecking ball. An even darker film noir, Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950), stars James Cagney as a violent gangster (in fact, his last great This year’s UCLA Festival of Preservation again presents a wonderful cross- gangster role) whose id is more monstrous than almost anything since Little section of American film history and genres, silent masterpieces, fictional Caesar. Add crooked cops and a world in which no one can be trusted, and shorts, full-length documentaries and television works. Our Festival opens you have a perfect film noir tale. with Robert Altman’s Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982). This restoration is the first fruit of a new project to preserve Our newsreel preservationist, Jeff Bickel, presents his restoration of John and restore the artistic legacy of Mr. -

The Crash of the Boston Electra / Michael N

The Story of Man and Bird in Conflict BirdThe Crash of theStrike Boston Electra michael n. kalafatas Bird Strike The Crash of the Bird Boston Electra Strike michael n. kalafatas Brandeis University Press Waltham, Massachusetts published by university press of new england hanover and london Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England One Court Street, Lebanon NH 03766 www.upne.com © 2010 Brandeis University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Designed by Katherine B. Kimball Typeset in Scala by Integrated Publishing Solutions University Press of New England is a member of the Green Press Initiative. The paper used in this book meets their minimum requirement for recycled paper. For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kalafatas, Michael N. Bird strike : the crash of the Boston Electra / Michael N. Kalafatas. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-58465-897-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Aircraft bird strikes—Massachusetts— Boston. 2. Aircraft accidents —Massachusetts— Boston. 3. Electra (Turboprop transports) I. Title. TL553.525.M4K35 2010 363.12Ј465—dc22 2010013165 5 4 3 2 1 Across the veil of time, for the passengers and crew of Eastern Airlines Flight 375, and for my grandchildren: may they fl y in safe skies The bell- beat of their wings above my head. —w. b. yeats, “The Wild Swans at Coole” Contents Preface: A Clear and Present Danger xi 1. -

21St-Century Moore Scholarship, a Bibliography in Progress

21st-Century Publications on Marianne Moore A Bibliography in Progress Allen, Edward. “‘Spenser’s Ireland,’ December 1941: Scripting a Response.” Twentieth Century Literature 63:4 (December 2017): 451-474. Ambroży-Lis, Paulina. “When a Sycamore Becomes an Albino Giraffe: On the Tension between the Natural and the Artificial in Marianne Moore’s ‘The Sycamore.’” In Jadwiga Maszewska and Zbigniew Maszewski, eds.,Walking on a Trail of Words: Essays in Honor of Professor Agnieszka Salska. Łódź, Poland: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łodzkiego, 2007. Anderson, David. “Marianne Moore’s ‘Fertile Procedure’: Fusing Scientific Method and Organic Form through Syllabic Technique.” Paideuma 33:2-3 (Fall- Winter 2004): 83-108. Arckens, Elien. “’In This Told-Backward Biography’: Marianne Moore against Survival in Her Queer Archival Poetry.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 44: 1 & 2 (Spring /Summer 2016): 111-127. Austin, Marité Oubrier. “Marianne Moore’s Translation of the Term Galand in the Fables of LaFontaine.” Papers on French Seventeenth Century Literature 28: 54 (2001): 81-91. Bazin, Victoria. “Editorial Compression: Marianne Moore at The Dial Magazine.” In Twenty-First Century Marianne Moore (2017): 131-47. ——. “Hysterical Virgins and Little Magazines: Marianne Moore’s Editorship of The Dial.” Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 4:1 (2013): 55- 75. ——. “'Just looking’ at the Everyday: Marianne Moore’s Exotic Modernism.” Modernist Cultures, 2:1 (May 2006): 58-69. ——. “Marianne Moore, and the Arcadian Pleasures of Shopping.” Women: A Cultural Review, 12:2 (. 2001): 218-235. ——. Marianne Moore and the Cultures of Modernity. Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2010. ——. “Marianne Moore, Kenneth Burke, and the Poetics of Literary Labor.” Journal of American Studies, vol.