Enrollment Preferences Task Force Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November/December 2008, Vol 17

SPECIAL EDITION Fall Conference • Top Urban Educator, p.2 • Immigration Issues, p. 3 • Conference Pictorial, p.9 • Ballot Results, p.10 The Nation’s Voice for Urban Education November/December 2008 Vol. 17, No. 8 www.cgcs.org New President Focus of Town Hall Meeting HOUSTON—Urban school leaders hosting the Council conference, called voiced their thoughts on “An Urban Edu- for national standards to measure school cation Agenda for the New President,” performance. “We can’t have a federal ac- the topic of a national town hall meeting countability system without national stan- held in conjunction with the Council of dards,” he stressed. the Great City Schools’ 52nd Annual Fall Lisa Graham Keegan, senior education Conference, Oct. 22-26, in Texas’ largest adviser to Sen. John McCain’s campaign, Letter to New President city. (View Town Hall Meeting) said that McCain does not believe in im- A packed ballroom of educators heard plementing mandatory national standards. HOUSTON—The Council of the from a panel that included education advis- Jonathan Schnur, who represented then- Great City Schools issued an Open Let- ers of the two presidential candidates, who Senator and now President-elect Barack ter to the Next President of the United faced off in a lively 90-minute discussion Obama, noted that Obama wants more States at its Fall Conference here. The moderated by noted journalist Dan Rather, consistency around high standards, and letter, featured in its entirety on page 6, global correspondent and managing editor wants to work with states and the federal reaches out to President-elect Barack of Dan Rather Reports on HDNet. -

151St General Assembly Legislative Guide 151St General Assembly Legislative Guide

151st General Assembly Legislative Guide 151st General Assembly Legislative Guide Senate – Table of Contents …………………………….…………………………...…….. i House of Representatives – Table of Contents ..….……………………..…….…...… ii General Assembly Email and Phone Directory ……………………………………..... iv Senate – Legislative Profiles ………………………………………………...………….... 1 House of Representatives – Legislative Profiles …..……………..……………….... 23 Delaware Cannabis Advocacy Network P.O. Box 1625 Dover, DE 19903 (302) 404-4208 [email protected] 151st General Assembly – Delaware State Senate DISTRICT AREA SENATOR PAGE District 1 Wilmington North Sarah McBride (D) 2 District 2 Wilmington East Darius Brown (D) 3 District 3 Wilmington West Elizabeth Lockman (D) 4 District 4 Greenville, Hockessin Laura Sturgeon (D) 5 Heatherbrooke, District 5 Kyle Evans Gay (D) 6 Talleyville District 6 Lewes Ernesto B. Lopez (R) 7 District 7 Elsmere Spiros Mantzavinos (D) 8 District 8 Newark David P. Sokola (D) 9 District 9 Stanton John Walsh (D) 10 District 10 Middletown Stephanie Hansen (D) 11 District 11 Newark Bryan Townsend (D) 12 District 12 New Castle Nicole Poore (D) 13 District 13 Wilmington Manor Marie Pinkney (D) 14 District 14 Smyrna Bruce C. Ennis (D) 15 District 15 Marydel David G. Lawson (D) 16 District 16 Dover South Colin R.J. Bonini (R) 17 District 17 Dover, Central Kent Trey Paradee (D) 18 District 18 Milford David L. Wilson (R) 19 District 19 Georgetown Brian Pettyjohn (R) 20 District 20 Ocean View Gerald W. Hocker (R) 21 District 21 Laurel Bryant L. Richardson (R) 22 151st General Assembly – Delaware House of Representatives DISTRICT AREA REPRESENTATIVE PAGE District 1 Wilmington North Nnamdi Chukquocha (D) 24 District 2 Wilmington East Stephanie T. Bolden (D) 25 District 3 Wilmington South Sherry Dorsey Walker (D) 26 District 4 Wilmington West Gerald L. -

Education Finance Fellows Class of 2018

Education Finance Fellows Class of 2018 Bios Colorado Edward Penner Senator Kevin Priola John Hess Representative Jeff Bridges Michigan Brita Darling Senator Martin Knollenberg Connecticut Representative Aaron Miller Representative John Hampton Mary Guerriero Delaware Mississippi Senator David Sokola Representative Richard Bennett Representative Debra Heffernan David Pray Alexa Scoglietti Montana Taylor Hawk Senator Mark Blasdel Idaho Representative Don Jones Senator Chuck Windor Pad McCracken Representative Wendy Horman New Jersey Illinois Liz Mahn Senator Kimberly Lightford Ohio Representative Will Davis Marcus Benjamin Kansas Utah Representative Brenda Dietrich Senator Howard Stephenson Colorado and fishing as well, and he and his family are avid skiers and snowboarders. Senator Kevin Priola Kevin attended the University of Colorado at Boulder Kevin Priola was born and raised in Adams County, where he graduated with a Business degree. While at Colorado. He attended Brighton public schools grow- CU, he joined in the Ralphie Handlers Program – the ing up, including both Regis Jesuit and Horizon High group of college students who train and tend to one of Schools. Since he was young, he has enjoyed baseball, America’s most well-loved mascots, Ralphie. Kevin was football and running. Kevin is now a big fan of hunting also active in politics at CU as a member of the College 2017 – 2018 1 Republicans. He spent much of his time hosting cau- because I was student there. But I’ve also worked with cuses and bringing awareness of political issues to his people from across the entire state, from the San Luis fellow students. Valley, the Western Slope, the Eastern Plains, and all along the Front Range. -

Education Finance Fellows Class of 2018

Education Finance Fellows Class of 2018 Bios Colorado John Hess Senator Kevin Priola Michigan Representative Jeff Bridges Senator Martin Knollenberg Brita Darling Representative Aaron Miller Connecticut Mary Guerriero Representative John Hampton Mississippi Delaware Representative Richard Bennett Senator David Sokola David Pray Representative Debra Heffernan Montana Meredith Seitz Senator Mark Blasdel Carling Ryan Representative Don Jones Idaho Pad McCracken Senator Chuck Windor New Jersey Representative Wendy Horman Liz Mahn Illinois Ohio Senator Kimberly Lightford Marcus Benjamin Representative Will Davis Utah Kansas Senator Howard Stephenson Representative Brenda Dietrich Edward Penner Colorado and fishing as well, and he and his family are avid skiers and snowboarders. Senator Kevin Priola Kevin attended the University of Colorado at Boulder Kevin Priola was born and raised in Adams County, where he graduated with a Business degree. While at Colorado. He attended Brighton public schools grow- CU, he joined in the Ralphie Handlers Program – the ing up, including both Regis Jesuit and Horizon High group of college students who train and tend to one of Schools. Since he was young, he has enjoyed baseball, America’s most well-loved mascots, Ralphie. Kevin was football and running. Kevin is now a big fan of hunting also active in politics at CU as a member of the College 2017 – 2018 1 Republicans. He spent much of his time hosting cau- OLLS acts as general counsel for the General Assem- cuses and bringing awareness of political issues to his bly, reviews all executive branch rulemaking, and annu- fellow students. ally publishes the Colorado Revised Statutes. In her 11 sessions with the General Assembly, Brita has drafted Kevin’s business background includes 15 years of busi- bills in her drafting team's subject-matter areas, includ- ness experience at Priola Greenhouses and CAP Prop- ing criminal justice, family law, human services, educa- erty Management. -

Insider's Guidetoazpolitics

olitics e to AZ P Insider’s Guid Political lists ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE ARIZONA CAPITOL TIMES • Arizona Capitol Reports FEATURING PROFILES of Arizona’s legislative & congressional districts, consultants & public policy advocates Statistical Trends The chicken Or the egg? WE’RE EXPERTS AT GETTING POLICY MAKERS TO SEE YOUR SIDE OF THE ISSUE. R&R Partners has a proven track record of using the combined power of lobbying, public relations and advertising experience to change both minds and policy. The political environment is dynamic and it takes a comprehensive approach to reach the right audience at the right time. With more than 50 years of combined experience, we’ve been helping our clients win, regardless of the political landscape. Find out what we can do for you. Call Jim Norton at 602-263-0086 or visit us at www.rrpartners.com. JIM NORTON JEFF GRAY KELSEY LUNDY STUART LUTHER 101 N. FIRST AVE., STE. 2900 Government & Deputy Director Deputy Director Government & Phoenix, AZ 85003 Public Affairs of Client Services of Client Public Affairs Director Development Associate CONTENTS Politics e to AZ ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE Insider’s Guid Political lists STAFF CONTACTS 04 ARIZONA NEWS SERVICE BEATING THE POLITICAL LEGISLATIVE Administration ODDS CONSULTANTS, DISTRICT Vice President & Publisher: ARIZONA CAPITOL TIMES • Arizona Capitol Reports Ginger L. Lamb Arizonans show PUBLIC POLICY PROFILES Business Manager: FEATURING PROFILES of Arizona’s legislative & congressional districts, consultants & public policy advocates they have ‘the juice’ ADVOCATES, -

March 4, 2021 Jeff Bezos Chief Executive Officer Amazon.Com, Inc

DELAWARE GENERAL ASSEMBLY LEGISLATIVE HALL DOVER, DELAWARE 19901 March 4, 2021 Jeff Bezos Chief Executive Officer Amazon.com, Inc. 410 Terry Ave. N Seattle, WA 98109 Andy Jassy Chief Executive Officer Amazon Web Services 410 Terry Ave. N Seattle, WA 98109 RE: Encouraging a free and fair National Labor Relations Board election Dear Mr. Bezos and Mr. Jassy: Last week President Biden delivered a clear and unequivocal message to Amazon, its many thousands of employees, and the American people: Workers in the United States have the right and the freedom to organize and to advocate for their best interests in the workplace, and no company has the right to silence their voices, period. We write to echo the President’s sentiments and strongly urge Amazon to respect a free and fair National Labor Relations Board election in Bessemer, Alabama that will have implications for workers all across the nation, including several thousand of our constituents in Delaware. Amazon has realized enormous success through the pandemic, reaping record profits while continuing to grow and expand its services to an ever greater number of customers. While technology and innovation play key roles in Amazon’s unprecedented achievements in the world of commerce, your company is built on its workers. Your professional accomplishments and your personal fortunes are directly attributable to the productivity of Amazon’s workforce. Please remember this as you direct your company strategy related to organized labor and the fair treatment of your employees. Reports of the tactics employed by Amazon to oppose the organization effort in Alabama are troubling to say the least. -

State Small Dollar Rule Comments

State Small Dollar Rule Comments All State Commenters State Associations Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Dakota, Oklahoma, • AL // Alabama Consumer Finance Association South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, • GA // Georgia Financial Services Association Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin • ID // Idaho Financial Services Association • IL // Illinois Financial Services Association State Legislators • IN // Indiana Financial Services Association • MN // Minnesota Financial Services Association • MO // Missouri Installment Lenders Association; • AZ // Democratic House group letter: Rep. Stand Up Missouri Debbie McCune Davis, Rep. Jonathan Larkin, • NC // Resident Lenders of North Carolina Rep. Eric Meyer, Rep. Rebecca Rios, Rep. Richard • OK // Independent Finance Institute of Andrade, Rep. Reginald Bolding Jr., Rep. Ceci Oklahoma Velasquez, Rep. Juan Mendez, Rep. Celeste • OR // Oregon Financial Services Association Plumlee, Rep. Lela Alston, Rep. Ken Clark, Rep. • SC // South Carolina Financial Services Mark Cardenas, Rep. Diego Espinoza, Rep. Association Stefanie Mach, Rep. Bruce Wheeler, Rep. Randall • TN // Tennessee Consumer Finance Association Friese, Rep. Matt Kopec, Rep. Albert Hale, Rep. • TX // Texas Consumer Finance Association Jennifer Benally, Rep. Charlene Fernandez, Rep. • VA // Virginia Financial Services Association Lisa Otondo, Rep. Macario Saldate, Rep. Sally Ann • WA // Washington Financial Services Association Gonzales, Rep. Rosanna Gabaldon State Financial Services Regulators -

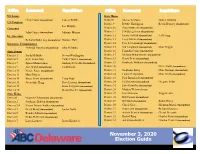

Informational Brochure

US Senate State House Chris Coons (incumbent) Lauren Witzke District8 Sherae’A Moore Daniel Zitofsky US Congress District 9 Debbie Harrington Kevin Hensley (incumbent) Lee Murphy Governor District 10 Sean Matthews (incumbent) John Carney (incumbent) Julianne Murray District 11 Jeff Spiegelman (incumbent) Lt. Governor District 12 Krista Griffith (incumbent) Jeff Cragg Bethany Hall-Long (incumbent) Donyale Hall District 13 Larry Mitchell (incumbent) Insurance Commissioner District 14 Pete Schwartzkopf (incumbent) Trinidad Navarro (incumbent) Julia Pillsbury District 15 Val Longhurst (incumbent) Mike Higgin State Senate District 16 Franklin Cooke (incumbent) District 1 Sarah McBride Steven Washington District 17 Melissa Minor-Brown (incumbent) District 5 Kyle Evans Gay Cathy Cloutier (incumbent) District 18 David Benz (incumbent) District 7 Spiros Mantzavinos Anthony Delcollo (incumbent) District 19 Kimberly Williams (incumbent) District 9 Jack Walsh (incumbent) Todd Ruckle District 20 Steve Smyk (incumbent) District 12 Nicole Poore (incumbent) District 21 Stephanie Barry Mike Ramone (incumbent) District 13 Mary Pinkey District 22 Luann D’Agostino Mike Smith (incumbent) District 14 Bruce Ennis (incumbent) Craig Pugh District 23 Paul Baumbach (incumbent) District 15 Jacqueline Hugg Dave Lawson (incumbent) District 24 Ed Osienski (incumbent) Gregory Wilps District 19 Brian Pettyjohn (incumbent) District 25 John Kowalko (incumbent) District 20 Gerald Hocker (incumbent) District 26 Madina Wilson-Anton State House District 27 Eric Morrison Tripp -

Nation's Largest-Ever School Choice Celebration to Kick Off In

Contact: Andrew Campanella President, National School Choice Week [email protected] or 850-837-0240 Nation’s Largest-Ever School Choice Celebration to Kick Off in Jacksonville Next Week School choice supporters to ring in National School Choice Week 2015 with Official Kickoff at Florida Theatre, January 23, 2015. US Sen. John McCain, Joe Trippi, Rev. HK Matthews, Superstar Athlete Desmond Howard to headline first of 11,000+ events nationwide JACKSONVILLE – The largest celebration of school choice in US history will officially start on Friday, January 23, 2015 at a special event in Jacksonville, Florida. National School Choice Week 2015 will kick off at the Florida Theatre at 12:30 pm on January 23. The event is the first event of an unprecedented 11,082 independently planned and independently funded special events taking place across all 50 states during the Week, which runs until January 31, 2015. The goal of the Week is to shine a positive spotlight on effective education options for children, and to raise awareness of the importance of, and benefits of, school choice in a variety of forms. More than 1,900 students, parents, and teachers will attend the Official Kickoff celebration, which will be nationally televised – on tape delay – on two cable television networks. The event’s speakers include: • US Senator John McCain (R-AZ), a longtime school choice supporter, who will be touring the NFL-YET Academy, a public charter school in Phoenix, and addressing a National School Choice Week event at the school. • Rev. HK Matthews, a noted civil rights pioneer who marched with Dr. -

Delaware Senate Journal

PRESENT: Senator(s) Adams, Amick, Blevins, Bonini, Bunting, Cloutier, Connor, Cook, Copeland, DeLuca, Henry, Marshall, McBride, McDowell, Peterson, Simpson, Sokola, Sorenson, Still, Vaughn, Venables - 21. The journal of the previous day was approved as read on motion of Senator McDowell. No objections. Senator McDowell welcomed former Presidents Pro Tempore, Richard S. Cordrey and Thomas B. Sharp visiting the chamber. Senator Amick was marked present. Senator McDowell also welcomed former Senator Robert B. Still, to the chamber. Senator McDowell extended best wishes to Senators Copeland, Blevins and DeLuca who celebrated birthdays recently. Senator Henry commented. Senator McDowell moved to recess for Party Caucus at 3:43 PM. The Senate reconvened at 5:30 PM with Lt. Governor Carney presiding. The Secretary announced a message from the House informing the Senate that it had passed HB 282; HB 276; SB 239; SB 248; SB 162 w/SA 1 & SA 2; SB 32. A communication from the Office of Senator Karen Peterson was read requesting Representative Ulbrich name be added as a co-sponsor of SB 253. A note from Senator Karen Peterson was read thanking her Senate colleagues for the expressions of sympathy upon the death of her mother. A communication from the Office of the Bishop of Wilmington, Most Reverend Michael A. Saltarelli, DD, thanking the Senate for Senate Resolution No. 16, was read to the record. LEGISLATIVE ADVISORY #15, dated January 31, 2006, the Governor signed the following legislation on the dates indicated: SB #249 (1/24/06) - AN ACT TO AMEND TITLE 5 OF THE DELAWARE CODE RELATING TO THE BANK FRANCHISE TAX. -

Debating Education

debating education EASTERN EVIDENCE DEBATE HANDBOOK 1999-2000 NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL DEBATE TOPIC PAGE ARGUMENT SECTION GENERAL 2 DEFINITIONS OF POLICY TERMS (NOT TOPICALITY) 5 TOPIC BACKGROUND ON EDUCATION REFORM 7 NEGATIVE VS. CASE 8 NO HARMS OR SIGNIFICANCE 28 NO SOLVENCY 126 NO INHERENCY 129 NEG AGAINST TECH IN SCHOOLS 138 NEGATIVE CASE TURNS 139 FOCUS ON GRADING IS BAD 148 FOCUS ON GOING TO COLLEGE IS BAD 153 BUREAUCRACY BARRIERS TURN CASE 158 SCHOOL REFORM IS COUNTERPRODUCTIVE 163 PRESSURE ON STUDENTS CAUSES HARMFUL STRESS 166 NEGATIVE COUNTERPLANS 167 STATES CP & FEDERALISM DA 194 DESCHOOLING COUNTERPLAN 230 RECONSTITUTION COUNTERPLAN 236 DISADVANTAGES 237 POLICY CHURN 241 DISABLING PROFESSIONS 252 LABELING 262 CURRICULUM TRADE OFF 272 PROPS UP CAPITALISM 282 INFRINGES ON STUDENTS RIGHTS 297 CRITIQUES 298 CRITIQUE OF CREDENTIALISM 308 CRITIQUE OF WORK 325 AFFIRMATIVES 326 AFF HARMS & SIGNIFICANCE GENERAL 340 AFF SOLVENCY GENERAL 345 AFF INHERENCY GENERAL POLICY DEBATE 2000 - EASTERN EVIDENCE HANDBOOK - http://debate.uvm.edu/ee.html 347 CHOICE/VOUCHER AFF 372 SCHOOL UNIFORM AFF 382 FIRST AFFIRMATIVE SPEECHES The diskette version has over 150 pages of evidence not in this handbook. The CD-ROM has the extra evidence, plus a video of a mini-debate for novices, extensive instructional materials, tournament software, and Internet research links. EASTERN EVIDENCE is a non-profit educational program of the Lawrence Debate Union and the University of Vermont. Lawrence Debate Union, 475 Main Street, UVM, Burlington, VT 05405; [email protected], 802-656- 0097 POLICY DEBATE 2000 - EASTERN EVIDENCE HANDBOOK - http://debate.uvm.edu/ee.html DEFINITIONS OF POLICY TERMS DEFINITION OF BEACON SCHOOLS Kelly C. -

Norfolk Southern Corporation Contributions

NORFOLK SOUTHERN CORPORATION CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL COMMITTEES JANUARY 1 ‐ DECEMBER 31, 2018* STATE RECIPIENT OF CORPORATE POLITICAL FUNDS AMOUNT DATE ELECTION OFFICE OR COMMITTEE TYPE IN Eric Holcomb $1,000 01/18/2018 Primary 2018 Governor US National Governors Association $30,000 01/31/2018 N/A 2018 Association Conf. Acct. SC South Carolina House Republican Caucus $3,500 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Cmte SC South Carolina Republican Party (State Acct) $1,000 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Cmte SC Senate Republican Caucus Admin Fund $3,500 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Non‐Fed Admin Acct SC Alan Wilson $500 02/14/2018 Primary 2018 State Att. General SC Lawrence K. Grooms $1,000 03/19/2018 Primary 2020 State Senate US Democratic Governors Association (DGA) $10,000 03/19/2018 N/A 2018 Association US Republican Governors Association (RGA) $10,000 03/19/2018 N/A 2018 Association GA Kevin Tanner $1,000 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA David Ralston $1,000 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Ryan Hatfield $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Gregory Steuerwald $500 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Karen Tallian $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State Senate IN Blake Doriot $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2020 State Senate IN Dan Patrick Forestal $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Bill Werkheiser $400 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Deborah Silcox $400 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Frank Ginn $500 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State Senate GA John LaHood $500 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State