Miscellaneous Christian Objections and Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

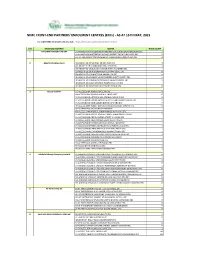

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Minority Report and Draft Constitution for the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1976

Minority Report and Draft Constitution for the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1976 By Olusegun Osoba and Yusufu Bala Usman With a New Introduction by Olusegun Osoba All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. © Olusegun Osoba and Yusufu Bala Usman ISBN e-book edition 978-574-69-1-4 First printed January 2019 i Dedication In memory of Yusufu Bala Usman and other fallen heroes of the struggle for a better Nigeria. ii Acknowledgements The publication of this book had its genesis in 2017, even before the creation of the Yusufu Bala Usman Institute, while some of us were associated with Ceddert. The initial idea came from Attahiru Bala Usman, who mentioned that people had been asking him where they could get copies of this rare but well known manuscript which was virtually impossible to obtain. It lay on shelves of activists and scholars since its initial launching as a mimeographed document in 1976 but had never been published. Thus we began the journey of reviving the document and getting it into print. First of all, we were not sure of the whereabouts of Dr. Segun Osoba, particularly since General Olusegun Obasanjo had pronounced him dead in his memoirs, My Watch, where he mentioned that both of the authors of the Minority Report were no longer alive. Fortunately we found that Dr. Osoba was very much alive and living in Ijebu Ode. -

Zuma-Nhis Health Care Providers

ZUMA-NHIS HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS HCP SN STATE State HCP NAME ADDRESS OF HCP 1 ABIA AB/0004 Abia State University Teaching Hospital ABA 2 ABIA AB/0005 Life Care Clinics Ltd 8, EZINKWU STREET, ABA AB/0007 JOHN OKARIE MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 12-14 AKABUOGU STREET OFF P.H. ROAD, ABA 3 ABIA 4 ABIA AB/0008 ST.ANTHONY'S HOSPITAL 62/80 ETCHE ROAD, ABA 5 ABIA AB/0013 DELTA HOSPITAL LTD. 78, FAULKS ROAD 6 ABIA AB/0014 Federal Medical Centre Umuahia UMUAHIA 7 ABIA AB/0015 OBIOMA HOSPITAL & MATERNITY 21, SCHOOL ROAD, UMUAHIA 8 ABIA AB/0016 Priscillia Memorial Hospital 32, BUNNY STREET 9 ABIA AB/0024 Living Word Hospital 5/7 UMUOCHAM STREET, ABA KILOMETRE 2 BENDE ROAD, UMUAHIA, ABIA 10 ABIA AB/0107 Healing Cross Hospital STATE 11 ADAMAWA AD/0021 Galbose Clinic MUBI ROAD, YOLA 12 ADAMAWA AD/0023 Dawau Clinic Ltd. JIMETA YOLA 13 ADAMAWA AD/0024 Peace Hospital YOLA 14 ADAMAWA AD/0048 Federal Medical Centre YOLA 15 ADAMAWA AD/0052 General Hospital Mubi MUBI 16 ADAMAWA AD/0084 Federal Polytechnic Clinic, Mubi MUBI The New Boshang Clinic and maternity KAREWA GRA, JIMETA-YOLA 17 ADAMAWA AD/0118 Ltd 18 ADAMAWA AD/0125 Da'ama Specialist Hospital 70/72 Atiku Abubakar Rd, Yola UYO, AKWA IBOM 19 AKWA IBOMAK/0012 University Of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo 20 AKWA IBOMAK/0045 University of Uyo Health Centre, Uyo UYO, AKWA IBOM 21 ANAMBRA AN/0002 General Hospital, Awka AWKA, ANAMBRA STATE 12. UMUDORA STREET, AWKA, ANAMBRA 22 ANAMBRA AN/0004 Beacon Hospital STATE. 9 KEN OKOLI STREET, OFF WORKS ROAD, 23 ANAMBRA AN/0005 Divine Hospital & Maternity AWKA, ANAMBRA STATE. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu -

AFR 44/05/94 Distr: UA/SC UA 219/94

EXTERNAL (for general distribution) AI Index: AFR 44/05/94 Distr: UA/SC UA 219/94 Prisoners of conscience / Death penalty 8 June 1994 NIGERIAAmeh Ebute, lawyer, former President of the Senate, leading member of the newly-formed National Democratic Coalition (NADECO) Chief Olusegun Osoba, former Governor of Ogun State Polycarp Nwite, former Senator O.A. Okoroafor, former Senator and several other pro-democracy activists The military government in Nigeria has arrested and charged with treason prominent critics who have urged it to step down in favour of a civilian government. Former members of the Senate and House of Representatives, which were dissolved after a military coup in November 1993, have called for the reinstatement of democratic institutions. The security police are currently seeking other pro-democracy activists, and Amnesty International fears that more prisoners of conscience will be imprisoned. Treason is an offence punishable by death in Nigeria. On 1 June 1994 former members of the Senate issued a statement urging General Sani Abacha, the head of the military government, to stand down as head of state. This followed a secret meeting on 30 May of about two-thirds of the disbanded 91-member senate. On 2 June the security police arrested Ameh Ebute, former President of the Senate, for having convened the meeting. On 3 June Chief Olusegun Osoba, former Governor of Ogun State, was arrested. On the same day former members of the House of Representatives met and also called on the military government to resign by 11 June; former civilian state governors were also reported to have held a meeting. -

Egba Indigenes in the Politics and Political Development of Nigeria

Greener Journal of Social Sciences ISSN: 2276-7800 Vol. 2 (1), pp. 009-018, February 2012. Research Article Egba Indigenes in the Politics and Political Development of Nigeria. *K. A. Aderogba, B. A Ogunyemi and Dapo Odukoya Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Tai Solarin University of Education, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author’s Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Egba indigenes have been very prominent in political history of Nigeria. The objective of the paper is to examine the political development of Nigeria and the roles played by Egba indigenes. Abeokuta founded in 1830 has been a notable settlement in Nigeria. The Egbas have been significant members of ruling political parties. They have contributed significantly to the political development of Nigeria. The likes of Adetokunbo Ademola, the Ransome Kuti family, Madam Tinubu, George Sodeinde Sowemimo, Wole Soyinka, Moshood Kashimawo Abiola, Olusegun Aremu Obasanjo, Olusegun Osoba, Dimeji Bankole and others cannot be forgotten in the political history and political development of Nigerian. The researchers listened to a number of radio and television documentary programmes. News paper cuttings, magazines and journals were read. The paper used oral interview conducted with some retired and active political party chieftains, the monarchs, and notable members of Nigerian public. Providence has bestowed it upon them to play active parts in the political affairs of Nigeria. Not even a single ethnic group has ever had it so good and in the political history and development of the country. However, whoever is in power needs to be supported and encouraged to move the nation ahead . Key Words: Egba indigenes, politics, political development, Nigeria. -

Asiwaju Bolanle Ahmed Adekunle Tinubu

This is the biography of Asiwaju Bolanle Ahmed Adekunle Tinubu. ASIWAJU: THE BIOGRAPHY OF BOLANLE AHMED ADEKUNLE TINUBU by Moshood Ademola Fayemiwo, PhD and Margie Neal-Fayemiwo, Ed.D Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/9183.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. ASIWAJU THE BIOGRAPHY OF BOLANLE AHMED ADEKUNLE TINUBU Moshood Ademola Fayemiwo and Margie Neal-Fayemiwo Copyright © 2017 by Moshood Ademola Fayemiwo & Margie Neal- Fayemiwo Paperback ISBN: 978-1-63492-251-7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, photocopying, recording or otherwise without written permission from the authors, except for brief excerpts in newspaper reviews. The editing format of this book used The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage revised and expanded edition by Alan Siegal and William Connolly 1999 with thanks. A Publication of The Jesus Christ Solution Center, DBA, USA in collaboration with Booklocker Publishing Company Inc. St Petersburg, Florida USA Printed on acid-free paper. Cover Design Concept: Muhammad Bashir, Abuja Nigeria Cover Design by: Todd Engel Photos: - Olanre Francis, Washington DC Photos and Inner Page Layout: Brenda van Niekerk, South Africa First Edition: 2017 The Jesus Christ Newspaper Publishing Company Nigeria Limited (RC: 1310616) Tel: 0812-198- 5505; Email: [email protected] The Jesus Christ Solution Center, DBA USA (FEIN: 81-5078881) and its subsidiaries are registered trademarks licensed to conduct legitimate business activities in the United States of America. -

History of Abeokuta

HISTORY OF ABEOKUTA The Abeokutas Verse 1 Verse 2 Lori Oke ati petele Abeokuta Ilu Egba Nibe l’agbe bi mi si O Ngo ni gbagbe re Nibe l’agbe to mi dagba O Ngo gbe o leke okan mi Ile Ominira B’ilu Odo Oya Emi o f’Abeokuta s’ogo Emi o maa yo l’ori Olumo Ngo duro, l’ori Olumo Emi o s’ogo yi l’okan mi Maa yo l’oruko Egba O Wipe Ilu olokiki O Emi Omo Lisabi L’awa omo Egba ngbe Chorus Chorus Ma yo, ma yo, ma yo o, Ma yo, ma yo, ma yo o, L’ori Olumo L’ori Olumo Ma yo, ma yo, ma yo o, Ma yo, ma yo, ma yo o, L’ori Olumo L’ori Olumo ABEOKUTA WAS FOUNDED in 1830 after the intertribal wars ravaged refugees in Egba forest from their original homes between 1817 and 1830. The name of the town "ABEOKUTA" was derived from the protection which the fleeing settlers sought under the Olumo Rock, now a tourist center in the town. Abeokuta means 'the refugees under a rock', signifying the protection which the Olumo Rock offered the refugees from possible attacks. The first and major of these series of internecine wars was the one which broke out as a result of an incident at Apomu Market, now in the Irewolede Local Government area of Osun State. In 1821, an Owu man who sold alligator peppers was at Apomu Market selling his wares. He laid them out in piles containing 200 peppers each. -

Feb 3, 2021.Cdr

High expectations in MOUAU as Iwe now new VC Pg 12, 13 @newsechonigeria @newsechonigeria @newsechonigeria ...Strong voice echoes the truth ISSN: 2736-0512 WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 3, 2021 VOL. 2 NO. 14 N150 Police seal Only payment off Ebonyi PDP can stop our strike Pg 10 Pg 3 Secretariat - Abia teachers Iwe Insecurity: At last IPOB, S'East governors agree Pg 8 on open grazing ban Umahi Kanu Orji Kalu’s arraignment Pg 7 Ugwuanyi laments poor Pg 2 adjourned, EFCC seeks transfer turn out to COVID-19 test Court throws out suit seeking Seplat, NGC raise Ugwu’s sack as Imo PDP $260m to complete Imo chairman Pg 7 gas project Pg 6 News Echo Wednesday, February 3, 2021 P a g e 2 NEWS From Uchenna Ezeadigwe, Awka Anambra Govt set to build ultra-modern nambra State Govern- Ament has concluded plans with a Private firm to international market build an Ultra-Modern In- site, adding that with the 10,000 shops on an expanse internet connectivity, access and faster under conducive state government to assist ternational Market at Isiagu presence of a financier, the of land of about 20.8 hec- roads, hospitals, schools, atmosphere. by providing an access road in Awka South Local Gov- Market will be completed tares will be under the Pri- commercial banks, Flyover Amuzie disclosed that to the site to ease movement ernment Area. on schedule. vate Public Partnership ar- Bridge and basement. the Market structure will of machines and equipment. Speaking to Newsmen The Secretary to the State rangement. The Chairman of the be completed in phases, Spokesperson of the part- in Awka, Governor Willie Government, Professor Obiano said on comple- firm, Chief Jude Amuzie, explaining that seventeen nering commercial bank, Mr. -

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS at JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS AT JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat. 22 Constitutition Crescent Aba 2 AB/0003 Janet Memorial Hospital 245 Aba-Owerri Road, Aba 3 AB/0004 Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba 4 AB/0005 Life Care Clinics Ltd 8, Ezinkwu Street, Aba 5 AB/0006 New Era Specialist Hospital 213/215 Ezikiwe Road, Aba 12-14 Akabuogu Street Off P.H. Road, 6 AB/0007 John Okorie Memorial Hospital Aba 7 AB/0013 Delta Hospital Ltd. 78, Faulks Road 8 AB/0014 Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia Umuahia, Abia State 9 AB/0015 Obioma Hospital & Maternity 21, School Road, Umuahia 10 AB/0016 Priscillia Memorial Hospital 32, Bunny Street 11 AB/0018 General Hospital, Ama-Achara Ama-Achara, Umuahia 12 AB/0019 Mendel Hospital & Diagnostic Centre Limited 20 Tenant Road, Abia 13 AB/0020 Clehansan Hospital & Maternity 17 Osusu Rd, Aba. 14 AB/0022 Alpha Inland Hospital 36 Glass Industry Road, Aba 15 AB/0023 Todac Clinic Ltd. 59/61 Okigwe Road,Aba 16 AB/0024 Living Word Hospital 5/7 Umuocham Street, Aba 17 AB/0025 Living Word Hospital 117 Ikot Ekpene Road, Aba 3rd Avenue, Ubani Estate Ogbor Hill, 18 AB/0027 Ebemma Hospital Aba 19 AB/0028 Horstman Hospital 32, Okigwe Road, Aba 45, New Umuahia Road Ogbor Hill, 20 AB/0030 Princess Mary Specialist Hospital Aba 21 AB/0031 Austin Grace Hospital 16, Okigwe Road, Aba 22 AB/0034 St. Paul Hospital 6-12 St. Paul's Road, Umunggasi, Aba 23 AB/0035 Seven Days Adventist Hospital Umuoba Road, Aba 10, Oblagu Ave/By 160 Faulks Road, 24 AB/0036 New Lead Hospital & Mat. -

Ethnic and Communal Clashes in Nigeria: the Case of the Sagamu 1999 Hausa-Yoruba Conflict (Pp

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 6 (3), Serial No. 26, July, 2012 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v6i3.10 Ethnic and Communal Clashes in Nigeria: The Case of the Sagamu 1999 Hausa-Yoruba Conflict (Pp. 135-149) Olubomehin, O. Oladipo - Department of History and Diplomatic Studies, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye, Ogun State, Nigeria Phone no: +234 803 406 9943 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Yoruba and the Hausas are among the largest, politically active and commercially inclined ethnic groups in Nigeria. While the Hausas live in the north of the country, the Yoruba dwell in the south western part. The trade in cattle and kola nut brought many Hausas to settle in the Remo-Yoruba town of Sagamu. Over the years, this trade became an avenue for both ethnic groups to develop a cordial and an harmonious relationship until the conflict of July 1999 which brought about far reaching impact not only on the town of Sagamu but also on the hitherto existing peaceful relationship between the two ethnic groups. Indeed, some of the effects of the conflict have remained till today. This paper attempts a historical analysis of the Hausa/Yoruba conflict. It examines the causes of the conflict and discusses its character and nature. Unlike previous studies on the subject of conflict and ethnicity, this paper brings out the central importance of culture in the inter-relationship between two ethnic groups in Nigeria. It shows that the failure to respect the culture of one ethnic group by the other was the root cause of the Yoruba/Hausa conflict. -

LIST of NATIONAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEES and ITS MEMBERS Committee on Devolution of Powers

LIST OF NATIONAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEES AND ITS MEMBERS Committee on Devolution of Powers S/N Name 1. Chief Ayo Adebanjo 2 Chief Barrister Gbadegesin Adedeji 3 Senator Anthony Adefuye 4 Chief Adeniyi Akintola 5 Dr Amadu A. Ali 6 Prof Jibril Aminu 7 His Royal Highness Asara A.Asara 8 Attah Obong Victor 9 Dr Tunji Braithwaite 10 Briggs Annkio 11 Alhaji Bashir M.Dalhatu 12 Danbatta Magaji 13 Prof Godini G.Darah 14 Alhaji Usman Faruk 15 Engr Abubakar Buba Galadinma 16 Dr Chief Dozie Ifedike 17 Sen. Ibrahim Nasiru Mantu 18 Dr Junaid Muhammad 19 Sen Ken Nnamani 20 Prof A.B.C.Nwosu 21 Prof Mrs Rose Onah 22 Mr Anthony Sani 23 Dr Haruna Usman Sanusi 24 Sen. Gbemi Saraki 25 Sen Jack Tilley Gyado 27 Mallam Tanko Yakassai 28 Hon Dr Haruna Yerima COMMITTEE ON POLITICAL RESTRUCTURING AND FORMS OF GOVERNMENT S/N Name 1 Prof Anya O.Anya 2 Arogbofa Basorun Seinde 3 Senator Ahmed Mohammed Aruwa 4 Dr Olatokunbo Awolowo-Dosumu 5 Pastor Tunde Bakare 6 Senator Nimi Barigha-Amanage 7 Senator Sa’aidu Mohammed Dansadau 8 Dr Sam Egwu 9 Chief Benjamin S.C. Elue 10 Chief Gary Enwo Igariwey 11 Chief Olu Falae 12 Hon Binta Masi Garba 13 Mallam Sule Yahya Hamma 14 Hon Mohammed Umara Kumalia 15 Senator Sa’aidu Umar Kumo 16 His Excellency Engr Abdulkadir A.Kure 17 Mohammed AVM Moukhtar 18 Dr Abubakar Sadiqque Mohammed 19 Prof Isa Baba Mohammed 20 Air Cdre Idongesit Nkanga 21 Gen Ike (rtd)Nwachukwu 22 Mr Nduka Obaigbena 23 Mr Peter Odili 24 Mr Yemi Odumakin 25 Dr Phillips O.Salawu 26 Amb.