Sampling for Microplastics in Beach Sand (Maia Mcguire, Phd, UF/IFAS Extension Sea Grant Agent)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extraction of Water Samples by Separatory Funnel 1. Scope And

Alpha Analytical, Inc. ID No.:2165 Facility: Mansfield Revision 8 Department: Organic Extractions Published Date:8/9/2013 10:58:53 AM Title: Extraction of Water Samples by Separatory Funnel 3510 Page 1 of 11 Extraction of Water Samples by Separatory Funnel References: EPA 3510C, SW-846, Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste: Physical/Chemical Methods, EPA SW-846, Update III, 1997. Method 8081B , Reference: SW-846, Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste: Physical/Chemical Methods, EPA SW-846, Update IV, February 2007. Method 8082A , Reference: SW-846, Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste: Physical/Chemical Methods, EPA SW-846, Update IV, February 2007. Method 8270D , Reference: SW-846, Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste: Physical/Chemical Methods, EPA SW-846, Update IV, February 2007 1. Scope and Application Matrices: This method is applicable to aqueous samples. Definitions: Refer to Alpha Analytical Quality Manual. This method describes the procedure for extracting water-insoluble and lightly water-soluble organic compounds from aqueous samples. The method also describes concentration techniques suitable for preparing the extract for the various determinative methods listed in Table 1. The data report packages present the documentation of any method modification related to the samples tested. Depending upon the nature of the modification and the extent of intended use, the laboratory may be required to demonstrate that the modifications will produce equivalent results for the matrix. Approval of all method modifications is by one or more of the following laboratory personnel before performing the modification: Area Supervisor, Department Supervisor, Laboratory Director, or Quality Assurance Officer. This method is restricted to use by or under the supervision of trained analysts. -

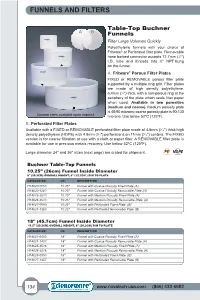

Funnels and Filters

51 FUNNELS AND FILTERS Buchner Funnels 260MM (10.25") INSIDE DIAMETER, 203MM (8") OVERALL HEIGHT, 127MM (5") RIM TO PLATE CATALOG NO. DESCRIPTION PRICE/EACH H14620-0000 Funnel with Coarse Porosity Fixed Plate $216.00 H14620-1260 Funnel with Coarse Porosity Removable Plate 216.00 H14625-3510 Funnel with Medium Porosity Fixed Plate 216.00 H14626-3510 Funnel with Medium Porosity Removable Plate 216.00 H14627-0000 Funnel with Perforated Fixed Plate 216.00 Table-Top H14627-1260 Funnel with Perforated Removable Plate 216.00 Buchner 457MM (18") INSIDE DIAMETER, 292MM (11.5") OVERALL HEIGHT, 203MM (8") RIM TO PLATE Funnels CATALOG NO. DESCRIPTION PRICE/EACH With Fritware® Porous H14621-0000 Funnel with Coarse Porosity Fixed Plate $540.00 Filter or HDPE H14621-1457 Funnel with Coarse Porosity Removable Plate 540.00 H14625-3518 Funnel with Medium Porosity Fixed Plate 540.00 Perforated Plate H14626-3518 Funnel with Medium Porosity Removable Plate 540.00 Polyethylene funnels are H14628-0000 Funnel with Perforated Fixed Plate 465.00 one piece design with a H14627-1457 Funnel with Perforated Removable Plate 465.00 FIXED or REMOVABLE Custom sizes available upon request. 610MM (24") INSIDE DIAMETER, 330MM (13") OVERALL HEIGHT, 267MM (10.25") RIM TO PLATE porous filter plate CATALOG NO. DESCRIPTION PRICE/EACH supported by a multiple ring grid. Filter plates are made of high density H14622-0000 Funnel with Coarse Porosity Fixed Plate $1125.00 1 polyethylene 6.4mm ( ⁄4") thick with a non-porous ring at the periphery of the plate H14622-1610 Funnel with Coarse Porosity Removable Plate 1125.00 1 H14625-3524 Funnel with Medium Porosity Fixed Plate 1125.00 which seals filter paper when used. -

Standard Operating Procedure SEA05 Laboratory Analysis-Version

Gulf Coast Network National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Division Standard Operating Procedure SEA05 Laboratory Analysis—Version 1.0 Please cite this as: Meiman, J. 2019. Laboratory Analysis—Version 1.0. Gulf Coast Network Standard Operating Procedure NPS/GULN/SOP—SEA05. Gulf Coast Network, Lafayette, Louisiana. Summary This standard operating procedure (SOP) for laboratory analysis of total suspended solids (TSS) is adopted verbatim from USEPA Method 160.2. Revision Log Revision Date Author Changes Made Reason for Change New Version # METHOD #: 160.2 Approved for NPDES (Issued 1971) TITLE: Residue, Non-Filterable (Gravimetric, Dried at 103–105°C) ANALYTE: Residue, Non-Filterable INSTRUMENTATION: Drying Oven STORET No. 00530 1. Scope and Application a. This method is applicable to drinking, surface, and saline waters, domestic and industrial wastes. b. The practical range of the determination is 4 mg / L to 20,000 mg / L. 2. Summary of Method a. A well-mixed sample is filtered through a glass fiber filter, and the residue retained on the filter is dried to constant weight at 103-105°C. b. The filtrate from this method may be used for Residue, Filterable. 3. Definitions a. Residue, non-filterable, is defined as those solids which are retained by a glass fiber filter and dried to constant weight at 103-105°C. 4. Sample Handling and Preservation a. Non-representative particulates such as leaves, sticks, fish, and lumps of fecal matter should be excluded from the sample if it is determined that their inclusion is not desired in the final result. b. Preservation of the sample is not practical; analysis should begin as soon as possible. -

Laboratory Equipment Reference Sheet

Laboratory Equipment Stirring Rod: Reference Sheet: Iron Ring: Description: Glass rod. Uses: To stir combinations; To use in pouring liquids. Evaporating Dish: Description: Iron ring with a screw fastener; Several Sizes Uses: To fasten to the ring stand as a support for an apparatus Description: Porcelain dish. Buret Clamp/Test Tube Clamp: Uses: As a container for small amounts of liquids being evaporated. Glass Plate: Description: Metal clamp with a screw fastener, swivel and lock nut, adjusting screw, and a curved clamp. Uses: To hold an apparatus; May be fastened to a ring stand. Mortar and Pestle: Description: Thick glass. Uses: Many uses; Should not be heated Description: Heavy porcelain dish with a grinder. Watch Glass: Uses: To grind chemicals to a powder. Spatula: Description: Curved glass. Uses: May be used as a beaker cover; May be used in evaporating very small amounts of Description: Made of metal or porcelain. liquid. Uses: To transfer solid chemicals in weighing. Funnel: Triangular File: Description: Metal file with three cutting edges. Uses: To scratch glass or file. Rubber Connector: Description: Glass or plastic. Uses: To hold filter paper; May be used in pouring Description: Short length of tubing. Medicine Dropper: Uses: To connect parts of an apparatus. Pinch Clamp: Description: Glass tip with a rubber bulb. Uses: To transfer small amounts of liquid. Forceps: Description: Metal clamp with finger grips. Uses: To clamp a rubber connector. Test Tube Rack: Description: Metal Uses: To pick up or hold small objects. Beaker: Description: Rack; May be wood, metal, or plastic. Uses: To hold test tubes in an upright position. -

Teacher Training Workshop for Educators of Students Who Are Blind Or Low Vision

Supalo et al.: Teacher Training Workshop for Educators of Students Who Are Blind or Low Vision Vol. 13, No. 1- Spring, 2009 Journal of Science Education for Students with Disabilities Teacher Training Workshop for Educators of Students Who Are ● , Danielle Dwyer, Heather, L. Eberhart, Blind or Low Vision Natasha Bunnag, Thomas E. Mallouk Cary A. Supalo, Danielle Dwyer, Heather L. Eberhart, Natasha Bunnag, and Thomas E. Mallouk Abstract: The Independent Laboratory Access for the Blind (ILAB) project has developed a suite of speech accessible tools for students who are blind or low vision to use in secondary and post- secondary science laboratory classes. The following are illustrations of experiments designed to be used by educators to introduce them to the ILAB tools, and to demonstrate how these tools can be incorporated into standard laboratory experiments. Information about the Lawrence Hall of Science’s SAVI/SELPH curriculum is also discussed. INTRODUCTION A 1993 study found that over 2/3 of graduates from the schools for the blind were unem- Residential schools for the blind have pro- ployed and a significant percentage received vided educational services to students who uncompetitive wages (6). In addition, only are blind or low vision (BLV) for well over 2.7% of the workforce in the science, technol- 100 years (1). In 1975, the passage of public ogy, engineering, and mathematics professions law 94-142 (Education of All Handicapped are physically disabled, and, of this percent- Children Act, later renamed the Individuals age, only a small number are blind (2). Provid- with Disabilities Education Act) started the ing blind and visually impaired students with trend for students who are blind to enter the the opportunity to work in a science labora- mainstream classroom (2). -

Portable Fluid Analysis Kit Manual

Donaldson Delivers Portable Fluid Analysis Kit Patch Test Kit Manual Kit Part Number X009329 Carrying Case Membrane Holder & Funnel Assembly P567863 Filter for Solvent Dispensing Bottle P567860 (Qty. 3) 500 ml Solvent Sampling Dispensing Bottle Pump P176431 Microscope 120 ml P567864 Sample Bottles (Qty. 6) Plastic Tubing P567861 (5 ft.) 1.2 micron Patch Covers Membrane P567912 (Qty. 150) Filters P567869 Zip Drive of (Qty. 100) Reference Information Membrane Filter Forceps Sharpie Analysis Cards (3”x5”) P567865 (Qty. 50) 5 micron Membrane Filters Marker P567868 (Qty. 50) Case Size: Height: 14.5”/368.3mm | Width: 19.25”/489mm | Depth: 7.75”/197mm | Case Weight: 9.95 lbs./4.51 kg 1 2 3 Assemble waste bottle, funnel- Install solvent* dispensing tube and Rinse the funnel-patch assembly patch assembly, and vacuum pump install solvent filter on end of the with the filtered solvent to remove to form the sample processing dispensing tube. background contamination. The assembly. Tighten the vacuum patch should not be in place for pump o-ring on the funnel-patch * Mineral spirits are the most this process. assembly tube by turning the commonly used solvent aluminum locking device. 2 • www.donaldson.com Patch Test Kit Manual 4 5 6 Separate the funnel from the patch Reattach the funnel to the filter Agitate the sample fluid bottle and supporter and install a filter patch patch base with filter patch. Twist pour 25ml into the funnel. 25ml with ink grid up. (If the patch has an lock the funnel to the base. is denoted by the first line on the ink grid) funnel (closest to the patch). -

Marsh Funnel

Marsh Funnel Summary: The Marsh Funnel was developed to provide a field measurement of the apparent viscosity of clay-thickened drilling mud. Provided that a conversion table has been developed, a modified Marsh Funnel can be used to provide a measure of apparent viscosities for gum-thickened and polymer- thickened products used in wildland fire operations. Without a conversion table, the flow-through times can be used to determine batch to batch consistency of a single product, and in limited circumstances to compare similar products. The directions for use of a Marsh Funnel are given below. The procedures for modifying the Marsh Funnel for use in determining the viscosity of long-term retardants (Forest Service modification) and the consistency of water enhancers (California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, CDF modification) are provided in the following pages. Materials: Marsh Funnel (Use small tip, 3/16” diameter, for low-viscosity products such as Phos-Chek 259 or Phos-Chek LC-95A. Use the large tip, 17/64” diameter, for high- viscosity products such as Phos-Chek D75.) Container marked to 1 quart, a tall straight-sided container is best Stopwatch or timer with a “time up” function Thermometer Method: 1. Allow the test sample to stand until it reaches room temperature (70°F) and all air bubbles are dissipated since both of these factors have an influence on viscosity. 2. Ensure that the properly modified funnel is clean and dry and secured in an upright position (a ring stand works fine). 3. Cover the funnel orifice with a finger while pouring the test sample through the screen until the sample exactly reaches the bottom of the screen. -

Laboratory Supplies and Equipment

Laboratory Supplies and Equipment Beakers: 9 - 12 • Beakers with Handles • Printed Square Ratio Beakers • Griffin Style Molded Beakers • Tapered PP, PMP & PTFE Beakers • Heatable PTFE Beakers Bottles: 17 - 32 • Plastic Laboratory Bottles • Rectangular & Square Bottles Heatable PTFE Beakers Page 12 • Tamper Evident Plastic Bottles • Concertina Collapsible Bottle • Plastic Dispensing Bottles NEW Straight-Side Containers • Plastic Wash Bottles PETE with White PP Closures • PTFE Bottle Pourers Page 39 Containers: 38 - 42 • Screw Cap Plastic Jars & Containers • Snap Cap Plastic Jars & Containers • Hinged Lid Plastic Containers • Dispensing Plastic Containers • Graduated Plastic Containers • Disposable Plastic Containers Cylinders: 45 - 48 • Clear Plastic Cylinder, PMP • Translucent Plastic Cylinder, PP • Short Form Plastic Cylinder, PP • Four Liter Plastic Cylinder, PP NEW Polycarbonate Graduated Bottles with PP Closures Page 21 • Certified Plastic Cylinder, PMP • Hydrometer Jar, PP • Conical Shape Plastic Cylinder, PP Disposal Boxes: 54 - 55 • Bio-bin Waste Disposal Containers • Glass Disposal Boxes • Burn-upTM Bins • Plastic Recycling Boxes • Non-Hazardous Disposal Boxes Printed Cylinders Page 47 Drying Racks: 55 - 56 • Kartell Plastic Drying Rack, High Impact PS • Dynalon Mega-Peg Plastic Drying Rack • Azlon Epoxy Coated Drying Rack • Plastic Draining Baskets • Custom Size Drying Racks Available Burn-upTM Bins Page 54 Dynalon® Labware Table of Contents and Introduction ® Dynalon Labware, a leading wholesaler of plastic lab supplies throughout -

Ultraviolet – Visible Spectroscopy for Determination of Α- and Β- Acids in Beer Hops

Isabella Pinque Chem219 Page 1 UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Analysis of Beer Hops date: 3/14/2018 Ultraviolet – Visible Spectroscopy For Determination of α- and β- acids in beer hops Isabella Pinque Lab Partner: Lucas Paquin TA: Kevin Fischer Date lab performed: 02/06/2018 Date report submitted: 03/14/2018 Isabella Pinque Chem 219 page 1 UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Analysis of Beer Hops date: 3/14/2018 ABSTRACT A spectrophotometric analysis at three wavelengths was used to determine the concentration of α-acids, β-acids, and a third component that is associated with the degradation of hops. Two different samples of a simple extraction of hops were analyzed using a Shimadzu UV2450 to determine the concentration of each component. While doing a three component analysis, the third break down component had the highest concentration within the hops sample (0.05391 g/L ± 0.00493) , followed by the α-acids (0.01507 g/L ± 0.001291) and finally β-acids (0.005062 ± 0.0004816). When doing a two component analysis, the α-acid had a higher concentration than the β-acids, 0.01783 ± 0.001539 and 0.004354 ± 0.0004520, respectively. When taking the percentage of all three components, the overall percent did not add up to 1 due to the fact that there are more than just three components in the samples. In conclusion, the α-acids are more prevalent in a sample of hops which can be taken into consideration when home brewing to achieve the bitterness and the flavor desired. INTRODUCTION Hops are an essential aspect of the brewing process that provide flavor and aromas due to the oils and resins that reside in the lupulin glands of a hops cone (1). -

Extraction Read 5.1 & 2.18 & 2.21 in Your Lab Text. Extraction Is A

Extraction Read 5.1 & 2.18 & 2.21 in your lab text. Extraction is a separation technique based on differences in solubilities of substances in two immiscible solvents (usually water and a water insoluble organic solvent). solubility in solvent 1 Kc = partition coefficient = ------------------------ solubility in solvent 2 example: Given compound A, K (ether:water) = 4.0, how much of A can be extracted from a solution of 10.0 g of A in 100 mL of water with a single portion of 100 mL of ether? X / 100 mL ether Kc = 4.0 = ------------------------------- (10.0 - X) / 100 mL water X = 8.0 grams of A extracted into the ether -same as above, but extract two times with 50 mL of ether each time. X / 50 mL ether first extraction: Kc = 4.0 = ------------------------- (10.0 - X) / 100 mL water X = 6.67 grams of A extracted Y / 50 mL ether second extraction: Kc = 4 0 = ----------------------------- (3.33 - Y) / 100 mL water Y = 2.22 grams of A extracted total extracted = X + Y = 6.67 + 2.22 = 8.89 grams ==> multiple extractions with smaller amounts of solvent are more efficient than a single extraction with the same total amount of solvent. DRYING: an organic liquid that has been in contact with water is "wet" (contains some water). To "dry" it, use an inorganic drying agent. See Table 2.1 in your lab text. EXTRACTION AND WASHING The processes of extraction and washing are mechanically the same. Extraction refers to the recovery of a desired substance from a complex mixture, while washing denotes the removal of unwanted material. -

Funnels and Filters

Funnels And Filters table-top Buchner A B Funnels Filter Large Volumes Quickly Polyethylene funnels with your choice of Fritware® or Perforated filter plate. Removable 1 hose barbed connector accepts 12.7mm ( ⁄2") 3 I.D. tube and threads into ⁄4" NPT bung on the funnel. A. Fritware® Porous Filter Plates FIXED or REMOVABLE porous filter plate supported by a multiple ring grid. Filter plates are made of high density polyethylene, 1 6.4mm ( ⁄4") thick, with a non-porous ring at the periphery of the plate which seals filter paper when used. Available in two porosities (medium and coarse). Medium porosity plate is 45-90 microns; coarse porosity plate is 90-130 Custom sizes available upon request. microns. Use below 52ºC (125ºF). B. Perforated Filter Plates 3 Available with a FIXED or REMOVABLE perforated filter plate made of 4.8mm ( ⁄16") thick high 3 7 density polyethylene (HDPE) with 4.8mm ( ⁄16") perforations on 11mm ( ⁄16") centers. The FIXED version is for coarse filtration or use with a cloth or paper filter. A REMOVABLE filter plate is available for use in precious metals recovery. Use below 52ºC (125ºF). Large diameter 24" and 36" sizes (next page) are crated for shipment. Buchner table-top Funnels 10.25” (26cm) Funnel Inside Diameter 8" (20.3Cm) Overall HeIgHt, 5” (12.7Cm ) rIm tO Plate CatalOg nO. I.D. DesCrIPtIOn H14620-0000 10.25" Funnel with Coarse Porosity Fixed Plate (A) H14620-1260 10.25" Funnel with Coarse Porosity Removable Plate (A) H14625-3510 10.25" Funnel with Medium Porosity Fixed Plate (A) H14626-3510 10.25" Funnel with Medium Porosity Removable Plate (A) H14627-0000 10.25" Funnel with Perforated Fixed Plate (B) H14627-1260 10.25" Funnel with Perforated Removable Plate (B) 18" (45.7cm) Funnel Inside Diameter 11.5" (29.2Cm) Overall HeIgHt, 8" (20.3Cm) rIm tO Plate CatalOg nO. -

William Collins & Kenny Miller

LABORATORY TECHNIQUES & EXPERIMENTS Organic Chemistry I William Collins & Kenny Miller The Lab Notebook and Grading A copy of Edison’s lab notebook. 1 SECTION 1 Chemistry 250-251 Lab Policies The lab is an integral and essential part of the Organic Chemistry c) Be aware of all safety precautions discussed in each experi- course. It must be completed satisfactorily in order for the student ment and in the prelab safety lecture. to receive credit for the course. Please note the following FLC d) Pay particular attention to proper ways of cleaning equip- policies. ment and disposing of chemical wastes. • The student must attend his/her scheduled lab section and e) Keep your drawer and equipment clean and organized for carry out the experiment in the week that it is scheduled. Un- efficient laboratory work. der extenuating circumstances, the student may attend a “make‑up” lab section at another time during the same week • All lab work should be written up and reported in a manner de- with the prior approval of the scheduled instructor and the scribed in this lab manual. Late lab books will receive lower make‑up instructor. Otherwise, credit will not be given for that grades. Please consult your laboratory instructor for further in- experiment. structions. • If the student fails to satisfactorily complete any experiment or fails to properly check out of lab at the end of the course, he/she may be assigned an incomplete (I) for the course or a failing grade (F). • In order to insure your safety in the laboratory, it is important to come well prepared to the lab each week: a) Please read all assigned material in this manual before each experiment.