Order Responding to Request That the Administrator Object to the Issuance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Round-The-Clock Shopping Returns As Macy's Brings

December 18, 2013 Round-the-Clock Shopping Returns as Macy’s Brings Back Its Overnight Hours at Select Stores Extended Store Hours and 24-Hour Shopping Starts Friday, Dec. 20 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Last minute holiday shoppers receive their Christmas presents early this year with the gift of extra time as Macy’s brings back its seasonal tradition, 24-hour shopping. Beginning Friday, Dec. 20 at 7 a.m., 37 Macy’s stores in select cities across the country including Macy’s Herald Square in New York City; Union Square in San Francisco; and State Street in Chicago will stay open overnight for four days in a row of non-stop shopping until Christmas Eve on Tuesday, Dec. 24 at 6 p.m. With a shorter shopping season, Macy’s customers will be able to enjoy 107 hours of ‘round- the-clock shopping to ensure that everyone on the list receives the very best gift. A customer service initiative since 2006, Macy’s 24-hour shopping is a holiday tradition that makes the season less hectic with stores remaining open all-night during the homestretch of the Christmas season. Less holiday crowds and shorter lines are an added bonus as Macy’s makes sure that time is on everyone’s side. In addition to the 24-hour stores, mostly all stores nationwide, except furniture galleries and select locations, will offer extended hours each night until 2 a.m. thru Dec. 23, making Macy’s the go-to store for gifting. “Overnight shopping at Macy’s has become a holiday tradition that last minute gift-givers count on to get them through the time crunch of the season,” said Peter Sachse, chief stores officer, Macy’s, Inc. -

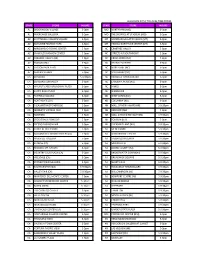

State Store Hours State Store Hours Al Brookwood

ALL HOURS APPLY TO LOCAL TIME ZONES STATE STORE HOURS STATE STORE HOURS AL BROOKWOOD VILLAGE 5-9pm MO NORTHPARK (MO) 5-9pm AL RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 5-9pm MO THE SHOPPES AT STADIUM (MO) 5-9pm AZ SCOTTSDALE FASHION SQUARE 5-9pm MT BOZEMAN GALLATIN VALLEY (MT) 5-9pm AZ BILTMORE FASHION PARK 5-9pm MT HELENA NORTHSIDE CENTER (MT) 5-9pm AZ ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 5-9pm NC CRABTREE VALLEY 5-9pm AZ CHANDLER FASHION CENTER 5-9pm NC STREETS AT SOUTHPOINT 5-9pm AZ PARADISE VALLEY (AZ) 5-9pm NC CROSS CREEK (NC) 5-9pm AZ TUCSON MALL 5-9pm NC FRIENDLY CENTER 5-9pm AZ TUCSON PARK PLACE 5-9pm NC NORTHLAKE (NC) 5-9pm AZ SANTAN VILLAGE 5-9pm NC SOUTHPARK (NC) 5-9pm CA CONCORD 5-9:30pm NC TRIANGLE TOWN CENTER 5-9pm CA CONCORD SUNVALLEY 5-9pm NC CAROLINA PLACE (NC) 5-9pm CA WALNUT CREEK BROADWAY PLAZA 5-9pm NC HANES 5-9pm CA SANTA ROSA PLAZA 5-9pm NC WENDOVER 5-9pm CA FAIRFIELD SOLANO 5-9pm ND WEST ACRES (ND) 5-9pm CA NORTHGATE (CA) 5-9pm ND COLUMBIA (ND) 5-9pm CA PLEASANTON STONERIDGE 5-9pm NH MALL OF NEW HAMPSHIRE 5-9:30pm CA MODESTO VINTAGE FAIR 5-9pm NH BEDFORD (NH) 5-9pm CA NEWPARK 5-9pm NH MALL AT ROCKINGHAM PARK 5-9:30pm CA STOCKTON SHERWOOD 5-9pm NH FOX RUN (NH) 5-9pm CA FRESNO FASHION FAIR 5-9pm NH PHEASANT LANE (NH) 5-9:30pm CA SHOPS AT RIVER PARK 5-9pm NJ MENLO PARK 5-9:30pm CA SACRAMENTO DOWNTOWN PLAZA 5-9pm NJ WOODBRIDGE CENTER 5-9:30pm CA ROSEVILLE GALLERIA 5-9pm NJ FREEHOLD RACEWAY 5-9:30pm CA SUNRISE (CA) 5-9pm NJ MONMOUTH 5-9:30pm CA REDDING MT. -

Kings Plaza Shopping Center 5100 Kings Plaza, Brooklyn, NY 11234

Kings Plaza Shopping Center 5100 Kings Plaza, Brooklyn, NY 11234 Tenant Design Criteria Section a Architectural Design Criteria Updated: July 2015 Kings Plaza Shopping Center 5100 Kings Plaza, Brooklyn, NY 11234 ADDENDUM LOG December, 2012 Updated to current layout January, 2013 Inserted front cover photo June, 2013 Replaced old drawings with new (a5-a8) January, 2014 Revised Walls/Partitions content (a19) December, 2014 Addition of LED lighting in public Tenant area shall be recessed (a19) February, 2015 Revised waterproof membrane beneath the finish floor surface up to 4”. (a20) April, 2015 All storefront metal panels must meet LL requirements (this note must appear on final drawing set). (a15) July 2015 Above normal sound levels must provide sound isolation (a18) Tenant Design Criteria Section a Architectural Design Criteria a2 Updated: July 2015 Addendum Log Kings Plaza Shopping Center 5100 Kings Plaza, Brooklyn, NY 11234 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN CRITERIA General Storefront Requirements a4 Neutral Pier Details a5-a8 Storefront Design Criteria a9-a14 Windows & Glazing a9 Rolling Grille Design Guidelines a10-a12 Awning Type, Awning Signage, Awning Logos a13 Overhangs, Umbrellas a14 Materials a15-a17 General Material Requirements, Metals, Stone, Wood a15 PLEASE VISIT WWW.MACERICH.COM TO VIEW PLAN SUBMITTAL & APPROVAL PROCEDURES and Tile, Pre-cast Stone and Concrete, CONTRACTOR’S RULES & REGULATIONS Plaster, Faux Finishes, Painted Surfaces a16 Prohibited Materials a17 Interiors a18-a21 DCA, Ceilings a18 Lighting, Walls/Partitions a19-a20 Floor and Wall Base a20 Toilet Room Requirements a21 Tenant Design Criteria Section a Architectural Design Criteria a3 Updated: July 2015 Table of Contents Kings Plaza Shopping Center 5100 Kings Plaza, Brooklyn, NY 11234 GENERAL STOREFRONT REQUIREMENTS All storefront designs and plans are subject to Landlord approval. -

Storename Address City State Zip Phone LAKEFOREST MALL 701

StoreName Address City State Zip Phone LAKEFOREST MALL 701 Russell Ave F-229 GAITHERSBURG MD 20877 301-987-2257 COLUMBIA MALL 10300 Little Patuxent Parkway 1067 COLUMBIA MD 21044 410-730-0030 REISTERSTOWN RD 9914 Reisterstown RD OWINGS MILLS MD 21117 410-581-2300 RT 81 & COLE RD 17221 COLE ROAD HAGERSTOWN MD 21740 301-582-3561 BALTIMORE NATIONAL PK & GEIPE RD 6425 BALTIMORE NATIONAL PIKE CATONSVILLE MD 21228 410-788-8258 RT 100 & I-40 9251 BALTIMORE NATIONAL PIKE ELLICOTT CITY MD 21042 410-465-3958 COLUMBIA MALL 3 10300 LITTLE PATUXENT PKWY 1310 COLUMBIA MD 21044 443-805-3499 REISTERSTOWN RD & LABYRINTH RD 6864 REISTERSTOWN ROAD BALTIMORE MD 21215 410-318-8971 Dobbin Rd & Dobbin Center Way 6365 Dobbin Rd Columbia MD 21045 443-218-2516 228 86TH & 2ND 228 East 86th Street NEW YORK NY 10028 212-535-6604 106TH & 3RD NYC 1910 3RD AVE NEW YORK NY 10029 212-423-9115 LEXINGTON & 89TH ST 1338 LEXINGTON AVE NEW YORK NY 10128 212-722-0712 3RD AVE & 72ND ST 1245 3RD AVENUE NEW YORK NY 10021 212-861-1984 3RD AVE & 55TH ST 914 3RD AVENUE NEW YORK NY 10022 212-421-2404 LEXINGTON AVE & 45TH ST 469 LEXINGTON AVENUE NEW YORK NY 10017 212-867-0781 1ST AVENUE & 14TH STREET 400 E. 14TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10009 646-329-4888 485 MADISON 485 Madison Ave NEW YORK NY 10022 646-735-3300 125TH & 5TH 55 West 125th Street NEW YORK NY 10027 212-996-9477 HOLYOKE MALL 3 50 HOLYOKE Ste D-263 HOLYOKE MA 01040 413-539-6031 RIVERDALE CENTER 935 Riverdale Street W. -

Kings Highway Plaza Anchored by Brooklyn, Nyc 2 Introducing Kings Highway Plaza with 80,000 Sf of New Construction Positioned at a Traffic

KINGS HIGHWAY PLAZA ANCHORED BY BROOKLYN, NYC 2 INTRODUCING KINGS HIGHWAY PLAZA WITH 80,000 SF OF NEW CONSTRUCTION POSITIONED AT A TRAFFIC LIGHT, EQUIPPED WITH ROOFTOP PARKING FOR 200+ CARS... IT’S CALLED KINGS FOR A REASON. READY FOR OCCUPANCY Q4 2019 SITE INFO 5200 KINGS HIGHWAY EAST FLATBUSH, BROOKLYN Size Demographics Retail 1 49,323 SF - Lower Level (Target) 5 Min 10 Min 15 Min Drivetime Drivetime Drivetime Retail 2 23,000 SF - Lower Level (Divisible) Retail 4 3,898 SF - Ground Floor Population 45,773 167,767 989,208 Retail 5 2,194 SF - Ground Floor Households 38,813 193,265 401,210 Average $91,112 $81,567 $77,331 Asking Rent Household Income Upon Request Total 2,586 14,222 30,283 Businesses Possession Q4/2019 Comments Currently Over 30,000 SF adjacent to new Target New Construction 200+ parking spaces at a traffic light intersection Frontage Located at the convergence of Kings Highway, Foster Ave, Utica Ave, and Glenwood Rd 270’ on Kings Highway Neighbors Over 128,000 total VPD on nearby major roads Kings Plaza Mall, BJ’s, Canarsie Plaza, CVS, Dollar Excellent visibility from all directions Tree Parking Free rooftop parking – 275 cars 4 TIMELINE TARGET SITE FOUNDATION UNDER RETAIL GRAND SIGNED BUILDING ANCHOR EXCAVATION COMPLETE CONSTRUCTION TOPPED OUT DELIVERY OPENING EXECUTED Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 2018 2018 2018 2019 2019 2019 2019 2020 2020 FLOOR PLANS MULTIPLE LEVELS OF DIVISIBLE RETAIL SPACES... ANCHORED BY TARGET. FLOOR PLANS PLAN A – LOWER LEVEL PLAN UTICA AVE. 16104NYKH No copies, transmissions, reproductions, or electro part be made without the express written permission drawings are property of Zyscovich Architects. -

Macerich to Add Primark Stores to Retail Lineups at Tysons Corner Center and Green Acres Mall

Macerich To Add Primark Stores To Retail Lineups At Tysons Corner Center And Green Acres Mall May 10, 2021 -New Deals Further Solidify Macerich's Relationship with Primark- SANTA MONICA, Calif., May 10, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- Macerich (NYSE: MAC), one of the nation's leading owners, operators and developers of one-of-a-kind retail and mixed-use properties in top markets, today announced new deals to bring Primark stores to two additional centers, Tysons Corner Center and Green Acres Mall. These new leases further solidify Macerich's relationship with Primark, as landlord to six of the brand's U.S. stores. The four other Primark stores in Macerich's portfolio include Danbury Fair Mall (open), Freehold Raceway Mall (open), Kings Plaza (open), and Fashion District Philadelphia (a two-level flagship store on Market Street now under construction and expected to open later this year). Leasing demand across the Macerich portfolio is on pace with pre-COVID 2019 levels, in large part due to the strength of the Company's high-quality town centers. In 2021, shopper traffic and sales are continuing to steadily rise with the loosening of restrictions within Macerich's major markets. The two new, two-level Primark stores are set for Tysons Corner Center, Macerich's powerhouse mixed-use property in Northern Virginia just outside Washington, D.C., and Green Acres Mall, the Company's well-positioned property located where New York City meets upmarket Long Island suburbs, replacing the recently closed JCPenney. Primark is a highly regarded international retailer known for its "Amazing Fashion at Amazing Prices," featuring clothing and accessories for women, men and kids, as well as beauty and homewares. -

Brooklyn Night Bus

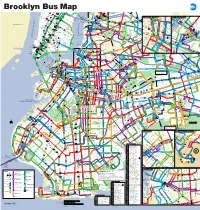

BBrrookkllyynn BBuuss Night Night M Mapap 1:00 AM to 5:00 AM Q 23 St ae E Northern Blvd nq 46 100 Queensboro Plaza CHELSEA 12 28 St 33 St Q n7 23 St Q 66 f MADISON AV Court Sq 39 E Queens Plaza HIGH LINE W 14 ST 23 St 46 7 23 St 65 St EIGHTH AV E E 37 AV 12 28 St HUNTERS 39 AV FEDERAL 36 AV ELEVATED 62 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn Court Sq 7 Q Downtown Brooklyn BUILDING LIC / Queens Plaza New Jersey PARK ae L 8 Av 18 St POINT 32 Roosevelt Av 14 St nq G 70 X Q70 SBS E 38 AV 23 St E 34 St / 21 St G Court Sq Q to LaGuardia SBS CADMAN PLAZA WEST 14 St 28 LEXINGTON AV THOMSO 46 ST Midtown 60 Q Q F ED KOCH 12 f Vernon Blvd - WOODSIDE TILLARY ST 14 St SUNNYSIDE 35 ST ROTUNDA East River Ferry Jackson Av N AV LIRR 53 70 Q 46 JACKSON AV YARD 39 ST 6 Av L Hunters Point South / 7 WOODSIDE SBS SBS GALLERY 26 62 66 23 St 42 ST QUEENSBORO BRIDGE UNION Long Island City 52 41 23 ST ST 7 33 St- 7 74 St- SQUARE LIRR Q 7 7 PIERREPONT ST Q BROADWAY E 23 ST WATERSIDE Rawson St 7 Bway East River Ferry HUNTERSPOINT AV 32 69 St Q LONG PARK LIRR 30 PL 100 PLAZA 7 7 40 St 7 52 St 61 St - 38 26 LONG Lowery St Woodside 32 ISLAND ISLAND Hunters SUNNYSIDE 7 Q IRVING PL 3 AV McGUINNESS BLVD Point Av 58 ST BROOKLYN 14 St- 11 ST Q CHRISTOPHER ST SEVENTH AV nql CITY 46 St QUEENS BLVD Q 60 Q 21 ST CITY Union Sq 30 ST HISTORICAL FAMILY QUEENS PLAZA S PETER 39 Bliss St 63 ST 1 2 AV 25 102 ROOSEVELT 101 21 St VAN DAM SOCIETY NY STATE JOHNSON ST F CRESCENT ST Christopher St 12 l 3 Av COOPER Q MONTAGUE ST COURT Queensbridge Sheridan Sq 48 AV 44 AV SUPREME 25 ISLAND VILLAGE -

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map To E 5757 StSt 7 7 Q M R C E BM Queensboro N W Northern Blvd Q Q 100 Plaza 23 St 23 St R W 5 5 AV 1 28 St 6 E 34 ST 103 69 Q WEST ST 66 33 St Court Sq 7 7 Q 37 AV Q18 to 444 DR 9 M CHELSEA F M 4 D 3 E E M Queens Astoria R Plaza Q104 to BROADWAY 23 St QUEENS MIDTOWN7 Court Sq - Q 65 St HIGH LINE W 14 S 23 ST 23 St R 7 46 AV 39 AV Astoria 18 M R 37 AV 1 X 6 Q FEDERAL 36 ELEVATED T 32 62 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza AV 47 AV D Q Downtown Brooklyn BUILDING 67 LIC / Queens Plaza 27 1 T Q PARK 18 St MADISON28 AVSt 32 ST Roosevelt Av 14 St A C E TUNNEL G Court Sq 58 ST 70 R W 67 212 ST 102 E ST 44 Q70 SBS L 8 Av X 28 S Q 6 S E F 38 T 4 TILLARY ST E 34 St / HUNTERSHUNTER BLV21 StSt G SKILLMAN AV SBS 103 AV 28 23 St VERNON to LaGuardia BACABAC F 14 St LEXINGTON AV T THOMSO 0 48 T O 6 Q Q M R ED KOCH Midtown 9 ST Q CADMAN PLAZA F M VernonVe Blvdlvd - 5 ST T 37 S WOODSIDE 1 2 3 14 St 3 LIRRRR 53 70 POINT JaJ cksonckson AvAv SUNNYSIDE S 104 ROTUNDA Q East River Ferry N AV 40 ST Q 2 ST EIGHTH AV 6 JACKSONAV QUEENS BLVD 43 AV NRY S 40 AV Q 3 23 St 4 WOODSIDEOD E TILLARY ST L 7 7 LIRR YARD SBS SBS 32 GALLERY 26 H N 66 23 Hunters Point South / 46 St T AV HE 52 41 QUEENSBORO 9 UNION E 23 ST M 7 L R 6 BROADWAY BRIDGEB U 6 Av HUNTERSPOINT AV 7 33 St- Bliss St E 7 Q32 E Long Island City A 7 7 69 St to 7 PIERREPONT ST W Q SQUARE Rawson St WOOD 69 ST 62 57 D WATERSIDE 49 AV T ROOSEV 61 St - Jackson G Q Q T 74 St- LONG East River Ferry T LIRR 100 PARK S ST 7 T Woodside Bway PARK AV S S 7 40 St S Heights 103 1 38 26 PLAZA -

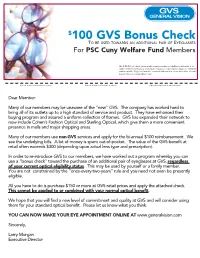

100 GVS Bonus Check to B E U S E D T O W a R D S a N a D D I T I O N a L P a I R O F Ey E G L a S S E S for PSC Cuny Welfare Fund Members

$100 GVS Bonus Check TO BE USED T OWARDS AN ADDI T IONAL PAIR OF EYEGLASSES For PSC Cuny Welfare Fund Members This $100 GVS gift check, can be used for family members not eligible for the benefit or for eligible members purchasing a second pair of eyeglasses or prescription sunglasses. Minimum purchase must be $150, and cannot be combined with vouchers or any other offers, sales and specials. This is not redeemable for cash. Cut out and present at time of service Cut out and present at time of service Cut out and present at time of service Dear Member: Many of our members may be unaware of the “new” GVS. The company has worked hard to bring all of its outlets up to a high standard of service and product. They have enhanced their buying program and assured a uniform collection of frames. GVS has expanded their network to now include Cohen’s Fashion Optical and Sterling Optical, which give them a more convenient presence in malls and major shopping areas. Many of our members use non-GVS services and apply for the bi-annual $100 reimbursement. We see the underlying bills. A lot of money is spent out-of-pocket. The value of the GVS benefit at retail often exceeds $300 (depending upon actual lens type and prescription). In order to re-introduce GVS to our members, we have worked out a program whereby you can use a “bonus check” toward the purchase of an additional pair of eyeglasses at GVS, regardless of your current optical eligibility status. -

NPD Participating Store List 2017

PRETZELMAKER National Pretzel Day Participating Store List ADDRESS I ADDRESS II CITY STATE ZIP PHONE NUMBER Village Mall Auburn 1627 Opelika Road,#10 Auburn AL 36830 (334) 821-8368 Brookwood Village 718 Brookwood Village Birmingham AL 35209 (205) 871-1333 Regency Mall 301 Cox Creek Parkway,Space #1302 Florence AL 35630 (256) 760-1980 Parkway Place Mall 2801 Memorial Parkway SW Huntsville AL 35801 (205) 539-3255 The Shoppes at EastChase 7048 EastChase Parkway Montgomery AL 36117 (334) 356-8111 Eastern Shore Centre 30500 State Hwy 181 Spc 810 Spanish Fort AL 36527 (251) 621-7977 Central Mall 5111 Rogers Avenue Fort Smith AR 72903 (479) 452-2525 Flagstaff Mall 4650 Northe Highway 89 Flagstaff AZ 86004 Desert Sky Mall 7611 West Thomas Rd. Phoenix AZ 85033 (623) 873-1540 Foothills Mall - Bakery Cafe 7401 N La Cholla Blvd #155 Tucson AZ 85741 (520) 531-8404 Tucson Mall 4500 N Oracle Rd Suite 212 Tucson AZ 85705 Park Place Mall 5870 East Broadway, #K-9 Tuscon AZ 85711 Sunrise Mall 6138 Sunrise Mall Citrus Heights CA 95610 (916) 723-7197 Solano Town Center 1350 Travis Blvd., Space B-13 Fairfield CA 94533 707-423-1942 Solano Town Center 1350 Travis Blvd, Space FC98 Fairfield CA 94533 Folsom Premium Outlet 13000 Folsom Blvd.,Suite 210 Folsom CA 95630-0002 (916) 351-1448 Del Monte Mall 520 Del Monte Center, U-526 Monterey CA 93940 (831) 646-0243 Moreno Valley Mall 22500 Town Cir Ste 1205 Moreno Valley CA 92553 (951) 653-2557 Galleria at Roseville 1151 Galleria Blvd.,#276 Roseville CA 95678 (916) 878-5418 Fashion Square at Sherman Oaks 14006 Riverside Drive,Space #86 Sherman Oaks CA 91423-6300 (818) 990-7161 Weberstown Mall 4950 Pacific Ave Stockton CA 95207 (209) 474-3466 The Oaks Mall 378 W. -

To Be Used Towards Your GVS Vision Benefits. to Enhance Your Benefit, GVS Is Offering an Additional $50 to Be Used by You Or a Family Member

$ FOR ALL ELIGIBLE MEMBERS 50 FOR YOU AND YOUR FAMILY To be used towards your GVS Vision Benefits. To enhance your benefit, GVS is offering an additional $50 to be used by you or a family member. If you have vision coverage, you can use this $50 bonus with your current benefit reducing any surcharges or upgrades for eyeglasses. Offer excludes contact lenses.SEE CARD FOR DETAILS. ONLY AT THESE SELECT GVS LOCATIONS NEW YORK Midtown West Cohen’s Fashion Optical Elmhurst Ridgewood General Vision @ MANHATTAN Cohen’s Fashion Optical 2933 Broadway Cohen’s Fashion Optical General Vision Express Court Street Chelsea 330 West 42nd St. (212) 662-0400 Queens Center Mall 57-52 Myrtle Ave. 66 Court Street General Vision @ (bet. 8th/9th Ave.) 90-15 Queens Blvd. (718) 497-2020 (btwn. Joralemon & Cohen’s Fashion Optical (212) 869-2020 Now Located At: (718) 592-5200 Livingston St.) 275 7th Ave. (25th Street) Cohen’s Fashion Optical Woodside (718) 923-2020 (212) 691-1709 Cohen’s Fashion Optical 2618 Broadway Flushing CN Vision Care 130 West 57th Street (Corner of 99th street) The Eye Shop 45-56 46th Street East New York East Side (212) 581-4967 (212) 666-2615 29-30 Union Street (718) 392-1244 Eyesite Vision II Cohen’s Fashion Optical (718) 359-7400 1125 Liberty Ave. 106 East 23rd Street Union Square Supreme Spectacle BROOKLYN (718) 235-7900 (Between Park and Cohen’s Fashion Optical 4250 Broadway Forest Hills Bay Parkway Lexington Ave.) 825 Broadway (212) 795-5640 General Vision @ Couture Optical NYC Flatbush (212) 677-3707 (b/w 12th & 13th Street) Cohen’s Fashion Optical 2313 65th Street General Vision @ (212) 475-0999 Lens Lab Express 116-53 Queens Blvd. -

Macy's Goes Round-The-Clock with 12 Specially Selected 24-Hour Stores for the Fourth Year in a Row

December 15, 2009 Macy's Goes Round-the-Clock with 12 Specially Selected 24-Hour Stores for the Fourth Year in a Row 83-Hour Shopping Marathon Begins at 7 a.m. on December 21 Through 6 p.m. on December 24 at Macy's Flagship in Herald Square; Seven New York City Metro, New Jersey, and DC Area Stores; Plus Four Midwest Stores in Chicago, Minneapolis and Detroit Area Four Additional NY and NJ Stores to Have Extended Hours until 2 a.m. NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- The homestretch of the holiday season will soon be upon countless shoppers still in need of finding the perfect gift. For the fourth year in a row, Macy's will give last minute shoppers some extra time with overnight and extended hours at select city and mall stores. Beginning on Monday, December 21 at 7 a.m., Macy's will open its doors at 12 select stores in the New York/New Jersey metro area, and the greater DC and Philadelphia metro areas for round-the-clock marathon shopping that goes the distance in delivering customer service and convenience. In addition to the twelve stores pulling all- nighters, four Macy's stores will extend their holiday hours until 2 a.m. from December 21 through December 23 for that much needed extra time to shop. 24-HOUR STORES -- Macy's Herald Square, New York, NY -- Macy's at Queens Center Mall, Rego Park, NY -- Macy's at Staten Island Mall, Staten Island, NY -- Macy's at Roosevelt Field Mall, Westbury, NY -- Macy's Cross County, Yonkers, NY -- Macy's at Willowbrook Mall, Wayne, NJ -- Macy's Tyson's Corner, McLean, VA -- Macy's Cherry Hill, Cherry Hill, NJ -- Macy's Woodfield, Schaumburg, IL -- Macy's Oakland, Troy, MI -- *Macy's Twelve Oaks, Novi, MI -- *Macy's Rosedale, Rosedale, MN (*) indicates stores that will remain open for 83-consecutive hours for the first time 2 a.m.