Climate Change and Gender Equality in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAINSTREAMING GENDER INTO CLIMATE MITIGATION ACTIVITIES Guidelines for Policy Makers and Proposal Developers

MAINSTREAMING GENDER INTO CLIMATE MITIGATION ACTIVITIES Guidelines for Policy Makers and Proposal Developers ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK MAINSTREAMING GENDER INTO CLIMATE MITIGATION ACTIVITIES Guidelines for Policy Makers and Proposal Developers By Eric Zusman, So-Young Lee, Ana Rojas, and Linda Adams Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2016 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2016. Printed in the Philippines. ISBN 978-92-9257-645-5 (Print), 978-92-9257-646-2 (e-ISBN) Publication Stock No. TIM168337 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Asian Development Bank. Mainstreaming gender into climate mitigation activities—Guidelines for policy makers and proposal developers Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2016. 1. Gender and Climate Change. 2. Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions and Nationally Determined Contributions. 3. Climate Finance. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Role of Women in Combating Climate Change”

i ii Compendium of invited talks and presentations National Seminar on “Role of Women in combating climate change” 7- 8 January 2010 Kerala State Council for Science, Technology and Environment Sasthra Bhavan Pattom Thiruvananthapuram & Co-sponsored by Department of Science & Technology, Government of India iii ROLE OF WOMEN IN COMBATING CLIMATE CHANGE Compendium of invited talks and presentations Editor in Chief Dr. C. T. S. Nair Executive Vice President, KSCSTE Compiled and Edited Dr. K. R. Lekha Scientist-E2 & Head ,Women Scientists’ Cell KSCSTE Secretarial assistance Ms. R. Asha Devi Ms. Meenu. V.S Published by: Kerala State Council for Science, Technology & Environment Sasthra Bhavan, Pattom (P.O), Thiruvananthapuram - 695 004 NOT FOR SALE 2010, KSCSTE, Govt. of Kerala No. of copies 150 NOTE: The views expressed in this Compendium is purely that of the authors and KSCSTE undertakes no responsibility on any of the points or views expressed by the authors in this Compendium. iv CONTENTSi Page No. Preface……………………………………………………………………………………..i Foreword…… Dr. C T S Nair, Executive Vice President, KSCSTE…………………….ii Acknowledgement……………………………………………………………………...iii Inaugural Address Smt. P.K. Sreemathy Teacher……….…………………………..…………………………………1 Presidential Address Dr. E.P. Yesodharan…………………………………….………………………………..………..3 About KSCSTE and background of the Seminar Dr. K.R. Lekha ………………………………………………………..………………….……….6 Women in the management of water resources Prof. J. Letha…………………………………….…………………………………………………8 The Science of Climate Change – Key Note Address Prof. J. Srinivasan……………………………………………………………………….………10 Climate change in relation to community health Dr. K Vijayakumar……………………………………………………………….…….……….17 Climate change and health – why gender matters? Dr. Manju R Nair……………………………………………………………….……… Waste management, Global warming and Climate change Shri. Jayaprasad S D ……………………………………………………………….……….….21 Interventions in Built Environment for reducing the Carbon Emissions Dr. -

Invest in Girls and Women to Tackle Climate Change and Conserve The

POLICY BRIEF Invest in Girls and Women to Tackle Climate Change and Conserve the Environment Facts, Solutions, Case Studies, and Calls to Action Empowering women to respond to the challenges posed by climate change is linked to the OVERVIEW achievement of the Sustainable Gender equality and climate change are inextricably linked. Girls and women are critical to the Development Goals (SDGs) and mitigation of and adaptation to climate change, despite usually being the first to face its adverse targets, including: consequences. As environmental degradation leads to increased poverty and hampers sustainable development, it is evident that dealing with and responding to climate change are critical to SDG 1: End poverty in all its achieving gender equality. forms everywhere Today, girls and women are on the frontlines of the fight against climate change and are often the first to respond to protect their families and communities. They are the innovators and changemakers, • 1.5 By 2030, build the resilience the ones who most often decide on the daily consumption of resources; play a key role in agricultural of the poor and those in production and land conservation; procure and consume water, cooking fuel, and other household vulnerable situations and reduce resources; and constitute the majority of climate migrants. As such, girls and women are not only their exposure and vulnerability well suited to find solutions to prevent environmental degradation and adapt to a changing climate, to climate-related extreme they have a vested interest in doing so. events and other economic, The first steps toward sustainably tackling the climate crisis are to ensure that girls and women are social, and environmental recognized for their progressive and forward-looking solutions for both people and the planet and shocks and disasters have a seat at the decision-making table. -

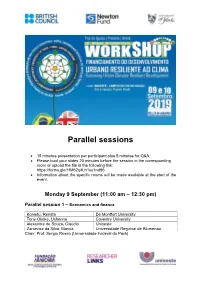

Parallel Sessions

Parallel sessions 15 minutes presentation per participant plus 5 minutes for Q&A. Please load your slides 20 minutes before the session in the corresponding room or upload the file in the following link: https://forms.gle/1fM62q4Lh1su1nd96 Information about the specific rooms will be made available at the start of the event. Monday 9 September (11:00 am – 12:30 pm) Parallel session 1 – Economics and finance Konadu, Renata De Montfort University Tony-Okeke, Uchenna Coventry University Alexandre de Souza, Claudio Unioeste Zanievicz da Silva, Marcia Universidade Regional de Blumenau Chair: Prof. Sergio Rivero (Universidade Federal do Pará) Parallel session 2 – Energy Buchmann, Kat Anglia Ruskin University Hartmann, Ricardo UNILA Ikpehai, Augustine Sheffield Hallam University Thakore, Renuka University College of Estate Management Chair: Dr. Stavros Afionis (University of Leeds) Monday 9 September (14:00 am – 15:30 pm) Parallel session 3 – Governance and policy Pinto da Silva, Maurício Universidade Federal de Pelotas Beling Loose, Eloisa Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Cesar Garcia, Julio UNIOESTE Amaral de Andrade, Bruno Federal University of Paraíba Chair: Prof. Carlos Eduardo Young (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro) Parallel session 4 – Environmental behaviour Ajala, Olayinka University of York Botti Capellari, Marta UNIOESTE Chrystianne Lucio Barros, Hellen Universidade Potiguar De Ita Velez, Cecilia University of Leeds Chair: Dr. Marco Sakai (University of York) Tuesday 10 September (11:00 am – 12:30 pm) Parallel session 5 – Water and resources Thorn, Jessica University of York Emerich Faria, Luciano Centro Universitário Newton Paiva Silva Santos, Claudiomir IFSULDEMINAS - Campus Muzambinho Jorge de Vasconcellos, Thaís Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Rio de Janeiro Chair: Dr. -

ASEAN Regional Guidelines for Promoting Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) Practices

ASEAN Regional Guidelines for Promoting Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) Practices Endorsed by the 37th AMAF 10 September 2015, Makati City, Philippines 1 Table of Contents 1. THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE ASEAN CLIMATE RESILIENCE NETWORK 1.1 Rationale and Background 1.2 ASEAN Frameworks and Structures relevant to Climate Change in Agriculture 1.3 Objectives of the ASEAN-CRN 1.4 Objectives of the Guidelines for Regional Cooperation on Climate Smart Agriculture Practices 1.5 Methodology and Process of developing the Guidelines 1.6 Selection of Crops and CSA Good Practices 2. GUIDELINES ON REGIONAL COOPERATION 1.7 Regional Cooperation on Scaling-up Climate Smart Agriculture Practices 3. TECHNICAL GUIDELINES ON GOOD PRACTICES 1.8 Stress Tolerant Maize Varieties 1.8.1 Synthesis of Technical Issues 1.8.2 Institutional and Technical Challenges 1.8.3 Regional Cooperation 1.8.4 Mechanism to Address Implementation 1.9 Stress Tolerant Rice Varieties 1.9.1 Synthesis of Technical Issues 1.9.2 Institutional and Technical Challenges 1.9.3 Regional Cooperation 1.9.4 Mechanism to Address Implementation 1.10 Agro Insurance Using Weather Indices 1.10.1 Synthesis of Technical and Institutional Issues 1.10.2 Institutional and Technical Challenges 1.10.3 Regional Cooperation 1.10.4 Mechanism to Address Implementation 3.5 Alternate Wetting and Drying 3.5.1 Synthesis of Technical Issues 3.5.2 Institutional and Technical Challenges 3.5.3 Regional Cooperation 3.5.4 Mechanisms to Address Implementation 3.6 Cropping Calendar for Rice and Maize 3.6.1 Synthesis of Technical -

Mexico Energy Efficiency Assessment for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Mitigation Final Report

MEXICO ENERGY EFFICIENCY ASSESSMENT FOR GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS MITIGATION FINAL REPORT Contract No.: AID-OAA-I-12-00038, Task Order: AID-OAA-TO-14-00007 8 January 2016 This report was produced for the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Crown Agents USA, Ltd. with Abt Associates, for the CEADIR project. CEADIR Mexico Energy Efficiency Assessment – Final Report Crown Agents USA, Ltd. 1 1129 20th Street NW 1 Suite 500 1 Washington DC 20036 1 T: (202) 822-8052 1 www.crownagentsusa.com With: Abt Associates Inc. CEADIR Mexico Energy Efficiency Assessment – Final Report MEXICO ENERGY EFFICIENCY ASSESSMENT FOR GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS MITIGATION FINAL REPORT Contract No.: AID-OAA-I-12-00038 Task Order AID-OAA-TO-14-00007 Prepared by: Crown Agents USA Ltd with Abt Associates Inc., Washington, DC. Santiago Enriquez, Abt Associates Eric Hyman, USAID Matthew Ogonowski, USAID José Luis Castro, Abt Associates Enrique Rebolledo, Abt Associates Carlos Muñoz, Abt Associates Gwendolyn Andersen, Abt Associates Itzá Castañeda, Crown Agents USA Submitted to: Offices of Economic Policy and Global Climate Change Bureau for Economic Growth, Education, and Environment US Agency for International Development 8 January 2016 DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this document reflect the personal opinions of the author and are entirely the authors’ own. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. USAID is not responsible for the accuracy of -

Compendium on Climate-Smart Irrigation

COMPENDIUM Climate-Smart Irrigation Compendium on Climate-Smart Irrigation Concepts, evidence and options for a climate- smart approach to improving the performance of irrigated cropping systems Compendium on Climate-Smart Irrigation Concepts, evidence and options for a climate- smart approach to improving the performance of irrigated cropping systems Charles Batchelor, Julian Schnetzer Global Alliance for Climate-Smart Agriculture Rome, 2018 CONTENTS CONTENTS .......................................................................................................... II FIGURES ............................................................................................................. VI PHOTOS ........................................................................................................... VIII TABLES ............................................................................................................... IX BOXES .................................................................................................................. X FOREWORD ......................................................................................................... XI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................... XII PREFACE .......................................................................................................... XIII LIST OF ACRONYMS ........................................................................................... XV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... -

Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change

UN WomenWatch: www.un.org/womenwatch The UN Internet Gateway on Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women Fact Sheet Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change Detrimental effects of climate change can be felt in the short-term through natural hazards, such as landslides, floods and hurricanes; and in the long-term, through more gradual deg- radation of the environment. The adverse ef- fects of these events are already felt in many areas, including in relation to, inter alia, ag- riculture and food security; biodiversity and ecosystems; water resources; human health; human settlements and migration patterns; and energy, transport and industry. In many of these contexts, women are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than men—primarily as they constitute the majority of the world’s poor and are more dependent for their livelihood on natural re- sources that are threatened by climate change. Photo Credit: UN Photo / Tim McKulka Furthermore, they face social, economic and political barriers that limit their coping ca- pacity. Women and men in rural areas in developing countries are especially vulnerable when they are highly dependent on local natural resources for their livelihood. Those charged with the responsibility to secure water, food and fuel for cooking and heating face the greatest challenges. Secondly, when coupled with unequal access to resources and to decision-making processes, limited mobility places women in rural areas in a position where they are disproportionately affected by climate change. It is thus important to identify gender-sensitive strategies to respond to the environmental and humanitarian crises caused by climate change.1 It is important to remember, however, that women are not only vulnerable to climate change but they are also effective actors or agents of change in relation to both mitigation and adaptation. -

Annotated Bibliography Climate Change, Migration, and Health 2018

Annotated Bibliography Climate Change, Migration, and Health 2018 This bibliography is a selective sampling of educational resources that introduce students to issues surrounding climate change, migration, and health. The multidisciplinary materials may be suitable for students at the undergraduate college and graduate school levels. Learning objectives and supporting materials will vary depending on how the material is used in a course. Brief annotations provide a cursory summary, and indicate where certain materials may be particularly relevant. Within each section, dated publications are listed in chronological order. This bibliography accompanies the teaching pack Climate Change, Migration, and Health. The materials listed here represent a diversity of viewpoints and opinions and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoints and opinions of the Incubator. The Global Health Education and Learning Incubator (GHELI) at Harvard University curates resource collections and teaching packs to equip students and educators with high-quality, accessible materials on priority topics, drawn from a range of sources and media. An expansive resource collection on climate, migration, and health is available at the GHELI online repository. This annotated bibliography includes: • Reports • Articles and Briefs • Data Publications, Portals, and Interactives • Country Profiles and Fact Sheets • Teaching Materials • Resource Packs This annotated bibliography was originally developed by the Global Health Education and Learning Incubator at Harvard University. It is used and distributed with permission by the Global Health Education and Learning Incubator at Harvard University. The Incubator’s educational materials are not intended to serve as endorsements or sources of primary data, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Harvard University. This resource is licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-NoDerivs3.0Unported [email protected] 617-495-8222 Climate Change, Migration, and Health: Annotated Bibliography Selected Resources – At a Glance REPORTS * Report. -

Women Farmers Adapting to Climate Change

09 Women Farmers I Climate Change DIALOGUE Women Farmers Adapting to Climate Change Four examples from three continents of women’s use of local knowledge in climate change adaptation Imprint Published by: Diakonisches Werk der EKD e.V. for “Brot für die Welt“ and Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe Stafflenbergstraße 76 D-70184 Stuttgart Germany Phone: ++49 711/2159-568 E-Mail: [email protected], info@diakonie-katastrophenhilfe www.brot-fuer-die-welt.de www.diakonie-katastrophenhilfe.de Authors: Seith Abeka, Saudia Anwer, Rocio Barrantes Huamaní, Vinod Bhatt, Stanley Bii, Betty Prissy Muasya, Amrita Rejina Rozario, Hugo Rojas Senisse, Gregorio Valverde Soría Editorial Staff: Ina Franke, Jörg Jenrich, Christine Lottje, Carsta Neuenroth Layout: Jörg Jenrich, Renate Zimmermann Responsible: Thomas Sandner Cover Photo: Christoph Püschner (Women farmers in Kenya) Art.Nr.: 129 601 320 Stuttgart, August 2012 Women Farmers Adapting to Climate Change Four examples from three continents of women’s use of local knowledge in climate change adaptation Contents Abbreviations 7 Introduction 8 1 Case Study India: Biodiversity-based organic farming with climate resilient crops 11 1.1 Introduction 11 1.2 Findings 12 1.2.1 The effects of climate change on women and men in the community 12 1.2.2 Existing coping strategies of women (and men) 13 1.2.3 Potential of women’s local knowledge for adaptation 17 1.2.4 Other aspects for successful adaptation 19 1.3 Contributing and hindering factors for the use of women’s local knowledge 19 1.3.1 Contributing factors -

Empowered Lives. Resilient Nations

From the Human Development Report Unit UNDP Asia-Pacific Regional Centre, Bangkok People in Asia-Pacific will be profoundly affected by climate change. Home to more than half of humanity, the region straddles some of the world's most geographically diverse and climate-exposed UNDP Asia-Pacic Human Development Fellowships areas. Despite having contributed little to the steady upward climb in the greenhouse gas emissions Academic that cause global warming, some of the region's most vulnerable communities — whether mountain Objective: To encourage and strengthen capacity among Ph.D. students from UNDP dwellers, island communities or the urban poor — face the severest consequences. Asia-Pacific programme countries to analyse issues from a human development perspective, contributing to cutting-edge research on theory, applications and policies. Poverty continues to decline in this dynamic region, but climate change may undercut hard-won gains. Growing first and cleaning up later is no longer an option, as it once was for the developed Media Empowered lives. countries. Developing nations need to grow and manage climate consequences at the same time. Objective: To develop capacity amongst media professionals from UNDP ResilientAsia-Pacific nations. They must both support resilience, especially among vulnerable populations, and shift to lower-carbon programme countries for enhanced reporting, dissemination and outreach campaigns to - pathways. Emerging threats, whether from melting glaciers or rising sea levels, cross borders and bring people’s issues to the centre of advocacy efforts. demand coordinated regional and global action. There may be some uncomfortable trade-offs, but the way forward is clear — it lies in sustaining Other Publications human development for the future we want. -

Invest in Women to Tackle Climate Change And

POLICY BRIEF Invest in Women to Tackle Climate Change and Conserve the Environment Facts, Solutions, Case Studies, and Policy Recommendations Empowering women to respond to the challenges OVERVIEW posed by climate change is linked to the achievement Climate change and environmental degradation represent a great threat to poverty reduction, gender of several SDGs and targets, equality and to achieving the SDGs. They impact health, food security, nutrition, production, migration, including: and people’s earnings. Given many women’s roles in agricultural production and as the procurers and consumers of water, cooking fuel, and other household resources, they are not only well suited to find SDG Goal 1: End poverty in all its solutions to prevent further degradation and adapt to the changing climate—they have a vested interest forms everywhere in doing so. The first step towards tackling the challenges of climate change is to create a backdrop • 1.5 By 2030, build the resilience of against which women are empowered to safeguard the environment. This policy brief examines some the poor and those in vulnerable useful strategies to promote the inclusion of women in climate change mitigation, adaptation, and situations and reduce their negotiations—and ensure their voices are heard. exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events SECTION 1: FRAMING THE ISSUE and other economic, social, and environmental shocks and disasters Climate change is increasing temperatures and affecting weather patterns, resulting in environmental degradation