Copyright by Yoon Soo Cho 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Researcher on Food Technology

SENIOR RESEARCHER ON FOOD TECHNOLOGY About IRTA IRTA is a research institute owned by the Government of Catalonia ascribed to the Department of Agriculture and Livestock. It is regulated by Law 04/2009, passed by the Catalan Parliament on 15 April 2009, and it is ruled by private regulations. IRTA is one of the CERCA centers of excellence of the Catalan Research System. IRTA’s purpose is to contribute to the modernization, competitiveness and sustainable development of agriculture, food and aquaculture sectors, the supply of healthy and quality foods for consumers and, generally, improving the welfare and prosperity of the society. THE PROGRAM OF FOOD TECHNOLOGY This Program is focused on answering the technological and research requirements of the agro-food industry. It has three main research lines: Food Engineering, Processes in the food industry, New process technologies. The Food Engineering research line works on: modelling transformation processes of food; transport operations (mass, heat and quantity of movement); process simulation and control; process engineering. Their scopes are: Drying Engineering studies the optimization of the traditional processes and the development of new drying systems. Optimization of traditional processes works in the modelling of mass transfer processes and transformation kinetics of foods in order to enhance their quality and energetic efficiency. New Technologies Engineering studies food packaging, transformation and preservation. Control systems are applied to raw material, processes and products The Processes in the Food Industry research line focuses on the improvement of traditional technologies in order to enhance quality, safety and sensorial characteristics of the product or the efficiency of the process. -

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment

Introduction To Flamenco: Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment by "Flamenco Chuck" Keyser P.O. Box 1292 Santa Barbara, CA 93102 [email protected] http://users.aol.com/BuleriaChk/private/flamenco.html © Charles H. Keyser, Jr. 1993 (Painting by Rowan Hughes) Flamenco Philosophy IA My own view of Flamenco is that it is an artistic expression of an intense awareness of the existential human condition. It is an effort to come to terms with the concept that we are all "strangers and afraid, in a world we never made"; that there is probably no higher being, and that even if there is he/she (or it) is irrelevant to the human condition in the final analysis. The truth in Flamenco is that life must be lived and death must be faced on an individual basis; that it is the fundamental responsibility of each man and woman to come to terms with their own alienation with courage, dignity and humor, and to support others in their efforts. It is an excruciatingly honest art form. For flamencos it is this ever-present consciousness of death that gives life itself its meaning; not only as in the tragedy of a child's death from hunger in a far-off land or a senseless drive-by shooting in a big city, but even more fundamentally in death as a consequence of life itself, and the value that must be placed on life at each moment and on each human being at each point in their journey through it. And it is the intensity of this awareness that gave the Gypsy artists their power of expression. -

A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz's Spanish Suite Op

A COMPARISON OF THE PIANO AND GUITAR VERSIONS OF ISAAC ALBÉNIZ'S SPANISH SUITE OP. 47 by YI-YIN CHIEN A LECTURE-DOCUMENT Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts November 2016 2 “A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz’s Spanish Suite, Op. 47’’ a document prepared by Yi-Yin Chien in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This document has been approved and accepted by: Jack Boss, Chair of the Examining Committee Date: November 20th, 2016 Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Boss, Chair Dr. Juan Eduardo Wolf Dr. Dean Kramer Accepted by: Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance © 2016 Yi-Yin Chien 3 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Yi-Yin Chien PLACE OF BIRTH: Taiwan DATE OF BIRTH: November 02, 1986 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Tainan National University of Arts DEGREES AWARDED: Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016, University of Oregon Master of Music, 2011, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Bachelor of Music, 2009, Tainan National University of Arts AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: Piano Pedagogy Music Theory PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: College Piano Teaching, University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance, 09/2014 - 06/2015 Taught piano lessons for music major and non-major college students Graduate Teaching -

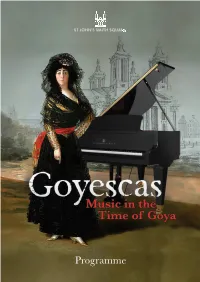

Music in the Time of Goya

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

Coastal Iberia

distinctive travel for more than 35 years TRADE ROUTES OF COASTAL IBERIA UNESCO Bay of Biscay World Heritage Site Cruise Itinerary Air Routing Land Routing Barcelona Palma de Sintra Mallorca SPAIN s d n a sl Lisbon c I leari Cartagena Ba Atlantic PORTUGALSeville Ocean Granada Mediterranean Málaga Sea Portimão Gibraltar Seville Plaza Itinerary* This unique and exclusive nine-day itinerary and small ship u u voyage showcases the coastal jewels of the Iberian Peninsula Lisbon Portimão Gibraltar between Lisbon, Portugal, and Barcelona, Spain, during Granada u Cartagena u Barcelona the best time of year. Cruise ancient trade routes from the October 3 to 11, 2020 Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea aboard the Day exclusively chartered, Five-Star LE Jacques Cartier, featuring 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada the extraordinary Blue Eye, the world’s first multisensory, underwater Observation Lounge. This state-of-the-art small 2 Lisbon, Portugal/Embark Le Jacques Cartier ship, launching in 2020, features only 92 ocean-view Suites 3 Portimão, the Algarve, for Lagos and Staterooms and complimentary alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages and Wi-Fi throughout the ship. Sail up Spain’s 4 Cruise the Guadalquivir River into legendary Guadalquivir River, “the great river,” into the heart Seville, Andalusia, Spain of beautiful Seville, an exclusive opportunity only available 5 Gibraltar, British Overseas Territory on this itinerary and by small ship. Visit Portugal’s Algarve region and Granada, Spain. Stand on the “Top of the Rock” 6 Málaga for Granada, Andalusia, Spain to see the Pillars of Hercules spanning the Strait of Gibraltar 7 Cartagena and call on the Balearic Island of Mallorca. -

United States Consulate General Consular Section

United States Consulate General Consular Section Paseo Reina Elisenda, 23 - 08034 Barcelona, Spain Tel: (34) 93-280-22-27 - Fax: (34) 93-280-61-75 Email: [email protected] Web: Lawyers Engine Seach LIST OF ATTORNEYS ALL PRACTICES In the Consular District of Barcelona (As of February 2017) The Barcelona Consular District covers the provinces of Barcelona, Girona, Huesca, Lleida, Tarragona, Teruel, Zaragoza, and the Principality of Andorra. This list has been divided into sections, grouped by countries, autonomous communities, provinces and cities. The U.S. Consulate General in Barcelona, Spain assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability or reputation of, or the quality of services provided by, the following persons or firms. Inclusion on this list is in no way an endorsement by the Department of State or the U.S. Consulate in Barcelona. Names are listed alphabetically, and the order in which they appear has no other significance. The information in the list on professional credentials, areas of expertise and language ability is provided directly by the lawyers; the U.S. Consulate General in Barcelona is not in a position to vouch for such information. You may receive additional information about the individuals on the list by contacting the local bar association (or its equivalent) or the local licensing authorities. The Department of State (CA/OCS) has prepared an information sheet on retaining a foreign attorney that is available at this web site: Retaining a Foreign Attorney. Complaints should initially be addressed to the COLEGIO DE ABOGADOS (Bar Association) in the city involved; if you wish you may send a copy of the complaint to the U.S. -

Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2016 Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/306 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 29-77 (2016) Flamenco Jazz: An Analytical Study Peter Manuel Since the 1990s, the hybrid genre of flamenco jazz has emerged as a dynamic and original entity in the realm of jazz, Spanish music, and the world music scene as a whole. Building on inherent compatibilities between jazz and flamenco, a generation of versatile Spanish musicians has synthesized the two genres in a wide variety of forms, creating in the process a coherent new idiom that can be regarded as a sort of mainstream flamenco jazz style. A few of these performers, such as pianist Chano Domínguez and wind player Jorge Pardo, have achieved international acclaim and become luminaries on the Euro-jazz scene. Indeed, flamenco jazz has become something of a minor bandwagon in some circles, with that label often being adopted, with or without rigor, as a commercial rubric to promote various sorts of productions (while conversely, some of the genre’s top performers are indifferent to the label 1). Meanwhile, however, as increasing numbers of gifted performers enter the field and cultivate genuine and substantial syntheses of flamenco and jazz, the new genre has come to merit scholarly attention for its inherent vitality, richness, and significance in the broader jazz world. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL CHARACTER AS EXPRESSED IN PIANO LITERATURE Yong Sook Park, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Bradford Gowen, Professor of Music In the middle of the 19th century, many composers living outside of mainstream musical countries such as Germany and France attempted to establish their own musical identity. A typical way of distinguishing themselves from German, French, and Italian composers was to employ the use of folk elements from their native lands. This resulted in a vast amount of piano literature that was rich in national idioms derived from folk traditions. The repertoire reflected many different national styles and trends. Due to the many beautiful, brilliant, virtuosic, and profound ideas that composers infused into these nationalistic works, they took their rightful place in the standard piano repertoire. Depending on the compositional background or style of the individual composers, folk elements were presented in a wide variety of ways. For example, Bartók recorded many short examples collected from the Hungarian countryside and used these melodies to influence his compositional style. Many composers enhanced and expanded piano technique. Liszt, in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, emphasized rhythmic vitality and virtuosic technique in extracting the essence of Hungarian folk themes. Chopin and Szymanowski also made use of rhythmic figurations in their polonaises and mazurkas, often making use of double-dotted rhythms. Obviously, composers made use of nationalistic elements to add to the piano literature and to expand the technique of the piano. This dissertation comprises three piano recitals presenting works of: Isaac Albeniz, Bela Bartók, Frédéric Chopin, Enrique Granados, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Frederic Rzewski, Alexander Scriabin, Karol Szymanowski, and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. -

Section I - Overview

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Street Art Subject: Los Cazadores del Sur Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE STORY SYNOPSIS INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE SECTION III – RESOURCES .................................................................................................................6 TEXTS DISCOGRAPHY WEB SITES VIDEOS BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................9 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ...................................................................................... 11 Los Cazadores del Sur preparing for a work day. Still image from SPARK story, February 2005. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES Street Art Individual and group research Individual and group exercises SUBJECT Written research materials Los Cazadores del Sur Group oral discussion, review and analysis GRADE RANGES K-12, Post-Secondary EQUIPMENT NEEDED TV & VCR with SPARK story “Street Art,” about CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS duo Los Cazadores del Sur Music, Social Studies Computer with Internet access, navigation software, -

Towards an Ethnomusicology of Contemporary Flamenco Guitar

Rethinking Tradition: Towards an Ethnomusicology of Contemporary Flamenco Guitar NAME: Francisco Javier Bethencourt Llobet FULL TITLE AND SUBJECT Doctor of Philosophy. Doctorate in Music. OF DEGREE PROGRAMME: School of Arts and Cultures. SCHOOL: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Newcastle University. SUPERVISOR: Dr. Nanette De Jong / Dr. Ian Biddle WORD COUNT: 82.794 FIRST SUBMISSION (VIVA): March 2011 FINAL SUBMISSION (TWO HARD COPIES): November 2011 Abstract: This thesis consists of four chapters, an introduction and a conclusion. It asks the question as to how contemporary guitarists have negotiated the relationship between tradition and modernity. In particular, the thesis uses primary fieldwork materials to question some of the assumptions made in more ‘literary’ approaches to flamenco of so-called flamencología . In particular, the thesis critiques attitudes to so-called flamenco authenticity in that tradition by bringing the voices of contemporary guitarists to bear on questions of belonging, home, and displacement. The conclusion, drawing on the author’s own experiences of playing and teaching flamenco in the North East of England, examines some of the ways in which flamenco can generate new and lasting communities of affiliation to the flamenco tradition and aesthetic. Declaration: I hereby certify that the attached research paper is wholly my own work, and that all quotations from primary and secondary sources have been acknowledged. Signed: Francisco Javier Bethencourt LLobet Date: 23 th November 2011 i Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank all of my supervisors, even those who advised me when my second supervisor became head of the ICMuS: thank you Nanette de Jong, Ian Biddle, and Vic Gammon.