“Raymond F. Collins' Study of the Practice of Celibacy in Latin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

LES ENLUMINURES,LTD Les Enluminures

LES ENLUMINURES,LTD Les Enluminures 2970 North Lake Shore Drive 11B Le Louvre des Antiquaires Chicago, Illinois 60657 2 place du Palais-Royal 75001 Paris tel. 1-773-929-5986 fax. 1-773-528-3976 tél : 33 1 42 60 15 58 [email protected] fax : 33 1 40 15 00 25 [email protected] BONIFACE VIII (1294-1303), Liber Sextus, with the Glossa Ordinaria of Johannes Andreae and the Regulae Iuris In Latin, illuminated manuscript, on parchment [France, likely Avignon, c. 1350] 228 folios, parchment, complete (1-910, 10 8, 1112, 12 8, 13-1412, 15-1910, 2011, 199 is a folio detached, 21-2210, 234, 225 and 227 are detached folios), quires 21 to 23 bear an old foliation that goes from 1 to 22 and are distinctive both by their mise-en-page and their texts, horizontal catchwords for quires 1-9 and 21-22, vertical for quires 10-20, ruling in pen: for the Liber Sextus 2 columns of variable length with surrounding glosses (57-60 lines of gloss; justification 295/325 x 195/200 mm); in quires 21-23, 2 columns (52-54 lines, justification 310 x 185), written in littera bononiensis by several hands, smaller and more compressed for the gloss, of middle size, more regular and larger for the Regulae iuris, decoration of numerous initals in red and blue, that of quires 1 and 5 is a little more finished, the initials there are delicately calligraphed with penwork in red with violet and blue with red, large 4 ILLUMINATED INITIALS on ff. 2r and 4r, a little deteriorated in blue, pale green, pink, orange, and gold and silver on black ground with white foliage, containing rinceaux and animals, the first surmounted by a rabbit; at the beginning of the text a large initial with penwork and foliage, ending in a floral frame separating the text from the gloss, with an erased shield in the lower margin. -

The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St

NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome About NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome Title: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.html Author(s): Jerome, St. Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) (Editor) Freemantle, M.A., The Hon. W.H. (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Print Basis: New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892 Source: Logos Inc. Rights: Public Domain Status: This volume has been carefully proofread and corrected. CCEL Subjects: All; Proofed; Early Church; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. Fathers of the Church, etc. NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome St. Jerome Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page.. p. 1 Title Page.. p. 2 Translator©s Preface.. p. 3 Prolegomena to Jerome.. p. 4 Introductory.. p. 4 Contemporary History.. p. 4 Life of Jerome.. p. 10 The Writings of Jerome.. p. 22 Estimate of the Scope and Value of Jerome©s Writings.. p. 26 Character and Influence of Jerome.. p. 32 Chronological Tables of the Life and Times of St. Jerome A.D. 345-420.. p. 33 The Letters of St. Jerome.. p. 40 To Innocent.. p. 40 To Theodosius and the Rest of the Anchorites.. p. 44 To Rufinus the Monk.. p. 44 To Florentius.. p. 48 To Florentius.. p. 49 To Julian, a Deacon of Antioch.. p. 50 To Chromatius, Jovinus, and Eusebius.. p. 51 To Niceas, Sub-Deacon of Aquileia. -

Collectio Avellana and Its Revivals

The Collectio Avellana and Its Revivals The Collectio Avellana and Its Revivals Edited by Rita Lizzi Testa and Giulia Marconi The Collectio Avellana and Its Revivals Edited by Rita Lizzi Testa and Giulia Marconi This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Rita Lizzi Testa, Giulia Marconi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2150-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2150-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. viii Rita Lizzi Testa I. The Collectio Avellana and Its Materials Chapter One ............................................................................................................... 2 The Power and the Doctrine from Gelasius to Vigile Guido Clemente Chapter Two............................................................................................................. 13 The Collectio Avellana—Collecting Letters with a Reason? Alexander W.H. Evers Chapter Three ......................................................................................................... -

Addressing Conflict in the Fifth Century: Rome and the Wider Church

_full_journalsubtitle: Journal of Patrology and Critical Hagiography _full_abbrevjournaltitle: SCRI _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 1817-7530 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1817-7565 (online version) _full_issue: 1 _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (change var. to _alt_author_rh): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (change var. to _alt_arttitle_rh): Addressing Conflict in the Fifth Century _full_alt_articletitle_toc: 0 _full_is_advance_article: 0 92 Scrinium 14 (2018) 92-114 Neil www.brill.com/scri Addressing Conflict in the Fifth Century: Rome and the Wider Church Bronwen Neil Macquarie University and University of South Africa [email protected] Abstract In seeking to trace the escalation, avoidance or resolution of conflicts, contemporary social conflict theorists look for incompatible goals, differentials in power, access to social resources, the exercise of control, the expression of dissent, and the strategies employed in responding to disagreements. It is argued here that these concepts are just as applicable to the analysis of historical doctrinal conflicts in Late Antiquity as they are to understanding modern conflicts. In the following, I apply social conflict theory to three conflicts involving the late antique papacy to see what new insights it can proffer. The first is Zosimus's involvement in the dispute over the hierarchy of Gallic bishops at the beginning of the fifth century. The second and longest case-study is Leo I's interven- tion in the Chalcedonian conflict over the natures of Christ. The final brief study is the disputed election of Symmachus at the end of the fifth century. Keywords Christology – Council of Chalcedon – Late antique papacy – Leo I, pope – papal letters – social conflict theory – Symmachus, pope – Zosimus, pope The term “conflict” is usually read as a negative, especially when used in the same phrase as “religious”. -

Standard Version

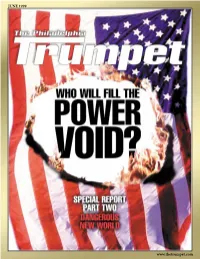

JUNE 1999 www.thetrumpet.com VOL. 10, NO. 5 — JUNE 1999 CIRC. 135,000 o COVER STORY PUBLISHER and EDITOR IN CHIEF Gerald Flurry SENIOR EDITORS Dennis Leap J. Tim Thompson Vyron Wilkins SPECIAL REPORT SECOND OF TWO PARTS : MANAGING EDITOR Stephen Flurry ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joel Hilliker CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Ryan Malone Donna Grieves Dangerous New World Deborah Leap Paula Powell Melody Thompson Magda Wilkins 2 Who Will Fill the Power Void? CONTRIBUTORS Eric Anderson Gareth Fraser Ron Fraser Shane Granger Andrew Locher United States and Britain Wilbur Malone 5 Gary Rethford Divided We Fall PHOTOGRAPHERS David Jardine Never have these two nations been so Stephen Flurry internally divided as over Kosovo. PREPRESS PRODUCTION Mark Carroll ON THE COVER: CIRCULATION Shane Granger 7 Flower-Power War NATO attacks have sparked anti-U.S. INTERNATIONAL EDITIONS EDITOR Wik Heerma 9 Disunited Kingdom sentiment worldwide. Here, an French Antonin Chiasson American flag burns. German Wik Heerma (Digital illustration by Joel Hilliker) Italian Daniel Frendo Spanish Jorge Esparza Germany and the Vatican OFFICE DIRECTORS Australasia Alex Harrison 14 The Fourth Reich in Disguise Canada Wayne Turgeon 16 Provocative Memoirs Caribbean J. Tim Thompson Central and South America Ron Fraser Britain, Europe, Middle East, Africa John Durrad China 21 THE PHILADELPHIA TRUMPET Feeding the Dragon (ISSN 10706348) is published monthly (except How America has catapulted China bimonthly March/April and September/October issues) by the Philadelphia Church of God, 1019 to center stage. And why. Waterwood Parkway, Suite F, Edmond, OK 73034. Periodicals postage paid at Edmond, OK, 26 China on the March 5 and additional mailing offices. -

Latin Derivatives Dictionary

Dedication: 3/15/05 I dedicate this collection to my friends Orville and Evelyn Brynelson and my parents George and Marion Greenwald. I especially thank James Steckel, Barbara Zbikowski, Gustavo Betancourt, and Joshua Ellis, colleagues and computer experts extraordinaire, for their invaluable assistance. Kathy Hart, MUHS librarian, was most helpful in suggesting sources. I further thank Gaylan DuBose, Ed Long, Hugh Himwich, Susan Schearer, Gardy Warren, and Kaye Warren for their encouragement and advice. My former students and now Classics professors Daniel Curley and Anthony Hollingsworth also deserve mention for their advice, assistance, and friendship. My student Michael Kocorowski encouraged and provoked me into beginning this dictionary. Certamen players Michael Fleisch, James Ruel, Jeff Tudor, and Ryan Thom were inspirations. Sue Smith provided advice. James Radtke, James Beaudoin, Richard Hallberg, Sylvester Kreilein, and James Wilkinson assisted with words from modern foreign languages. Without the advice of these and many others this dictionary could not have been compiled. Lastly I thank all my colleagues and students at Marquette University High School who have made my teaching career a joy. Basic sources: American College Dictionary (ACD) American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (AHD) Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE) Oxford English Dictionary (OCD) Webster’s International Dictionary (eds. 2, 3) (W2, W3) Liddell and Scott (LS) Lewis and Short (LS) Oxford Latin Dictionary (OLD) Schaffer: Greek Derivative Dictionary, Latin Derivative Dictionary In addition many other sources were consulted; numerous etymology texts and readers were helpful. Zeno’s Word Frequency guide assisted in determining the relative importance of words. However, all judgments (and errors) are finally mine. -

Jovinian: a Monastic Heretic in Late-Fourth Century Rome

JOVINIAN: A MONASTIC HERETIC IN LATE-FOURTH CENTURY ROME by NEIL BURNETT B. A. The University of Victoria, 1993. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Religious Studies) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1996 ©Neil Burnett, 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives, It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date il rffHiU mL DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT In 393 the monk Jovinian was condemned by a Roman synod under Pope Siricius. The monk had argued from Scriptural evidence that married women were equal in merit with widows and virgins; that they who had been baptised in fullness of faith could not be overthrown by the devil; that eating meats and drinking wine with thanksgiving was no less meritorious than abstention from these things; and that there was one reward in the kingdom of heaven for all those who had kept their baptismal vow. This paper is a reconstruction of Jovinian's arguments and motives from the evidence of Jerome's Against Jovinian. -

Theological Studies

The Journal of Theological Studies APRIL, 1813 Downloaded from THE DECRETAL OF DAMASUS.1 I HAVE recently had occasion to examine with closer attention the evidence for the genuineness of some documents the value of http://jts.oxfordjournals.org/ which as authorities I had hitherto been constrained to accept with more confidence than I can now. This has led me to modify some previously expressed views. Inasmuch as more learned men than myself have been my guides in this matter and it is one of considerable importance and interest, I may be allowed to begin this paper with a discussion of it. In the first volume of the Journal of Theological Studies at Columbia University Libraries on February 16, 2015 Mr C. H. Turner published the well-known text of the Decretal attributed to Damasus, who was Pope from 366 to 384, which, if a genuine document, is of prime value in the history of the Latin Canon of the Bible, since it contains a list of the books of the Bible professedly issued by that pope and consequently of very early date. In support of the genuineness and authority of the document he quotes the excellent recent names of A. Thiel, F. Maassen, and T. Zahn. Notwithstanding the gravity of the names I venture to ask for a reconsideration of this judgement. 1 The following pages were in type and corrected for press in October 1911, as the first part of Sir Henry Howorth's third article on ' The influence of St Jerome on the Canon of the Western Church' published in this JOURNAL in that month. -

Preface Celibacy and Tradition

". C)v.(U~-r~ 2D (h Iqif'tJ Joseph A. Komonchak Preface Celibacy and Tradition Well into the jourth century, the majority oj Bishops. priests and deacons were married. The author In 1978 the Natipnal Conference of Catholic Bishops' Committee traces the beginnings oj the discipline on Priestly Life and Ministry decided to undertake a study of Human of Celibacy and its development to Sexuality and the Ordained Priesthood. This decision was reached in our own day. response to concerns expressed to the Committee and as a service to the bishops and priests of the United States. As an initial step the Committee commissioned six papers to provide the necessary back- ground material for its work. These papers were to consider the posi- There are a few major disagreements among scholars as to the his- tions, analyses and respected opinions on various aspects of the ques- tory of the legislation on clerical celibacy. Well into the fourth cen- tion. Prepared by competent professionals, they proved helpful to the tury, the majority of the clergy (bishops, presbyters, and deacons) Committee and seemed likely to be of interest to a wider audience as were married and exercised their marriages even after ordination. well. The Committee therefore suggested that the authors submit them From early in the fourth century, marriages after ordination were reg- for publication. This was done, with the result that Chicago Studies is ulated and eventually forbidden, and rules were enacted forbidding now making them available in one issue. As presented herein, the pa- the ordination of digamists and of those who had married women pers represent the opinions of the various authors and not necessarily whose virginity could not be presumed. -

Sons of Don Bosco Successors of The

SONS OF DON BOSCO SUCCESSORS OF THE APOSTLES SALESIAN BISHOPS 1884 to 2001 by Charles N. Bransom, Jr. INTRODUCTION he study of apostolic succession and episcopal lineages has long fascinated students of church history. It was not until the middle T of the twentieth century, however, that a systematic attempt was made to trace and catalogue the consecrations of bishops on a world-wide basis. A small group of researchers has catalogued the consecrations of tens of thou sands of bishops dating back many centuries. The fruits of their labors--labors that are on going-have resulted in a database, which can trace the episcopal lineage of any living bishop and the vast majority of deceased bishops. In 1984, I began a project on the episcopal ordinations of bishops of re ligious orders and congregations. One fruit of that work was a study of the ordi nations of Salesian bishops, Les Eveques Salesiens. The present work updates, corrects and expands the 1984 study. In 1984, the episcopal ordinations of 130 bishops were presented. This study contains the details of 196 bishops. The text has been expanded to include the episcopal lineages of the bishops. Of the 196 bishops in this study, 183 trace their orders to Scipione Re biba, who was appointed Auxiliary Bishop ofChieti in 1541. The Rebiban suc cession is the major episcopal line in the contemporary Catholic episcopate. More than 91 % of the more than 4,500 bishops alive today trace their orders 54 Journal of Salesian Studies back to Rebiba Why so many bishops should trace their lineages to this one bishop can be explained, in great part, by the intense sacramental activity of Pope Benedict XIII, who consecrated 139 bishops during his pontificate, many of them cardinals, nuncios and bishops of important sees who in tum conse crated many other bishops.