2017 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original US

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUSKERS in MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL 35 Huskers Have Played in a Major League Baseball Game 9 World Series Rings - 9 All-Star Selections - 7 Gold Glove Awards

HUSKERS IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL 35 Huskers have Played in a Major League Baseball Game 9 World Series Rings - 9 All-Star Selections - 7 Gold Glove Awards BOB CERV (PLAYED AT NEBRASKA: 1947-50) STAN BAHNSEN (PLAYED AT NEBRASKA: 1965) MLB Career: 1951-62 MLB Career: 1968-83 Kansas City Athletics, New York Yankees, Los Angeles Angels, Houston Astros New York Yankees, Chicago White Sox, Oakland Athletics, Montreal Expos, California Angels, Philadelphia Phillies Honors World Series Champion (1956) Honors All Star (1958) American League Rookie of the Year (1968) Year Team G AVG AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO SB Year Team W-L SV ERA G GS CG SH IP H R ER BB SO 1951 NY-AL 12 .214 28 4 8 1 0 0 2 4 6 0 1966 NY-AL 1-1 1 3.52 4 3 1 0 23 15 9 9 7 16 1952 NY-AL 36 .241 87 11 21 3 2 1 8 9 22 0 1968 NY-AL 17-12 0 2.05 37 34 10 1 267.1 216 72 61 68 162 1953 NY-AL 8 .000 6 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1969 NY-AL 9-16 1 3.83 40 33 5 2 220.2 222 102 94 90 130 1954 NY-AL 56 .260 100 14 26 6 0 5 13 11 17 0 1970 NY-AL 14-11 0 3.33 36 35 6 2 232.2 227 100 86 75 116 1955 NY-AL 55 .341 85 17 29 4 2 3 22 7 16 4 1971 NY-AL 14-12 0 3.35 36 34 14 3 242 221 99 90 72 110 1956 NY-AL 54 .304 115 16 35 5 6 3 25 18 13 0 1972 Chi-AL 21-16 0 3.60 43 41 5 1 252.1 263 107 101 73 157 1957 KC-AL 124 .272 345 35 94 14 2 11 44 20 57 1 1973 Chi-AL 18-21 0 3.57 42 42 14 4 282.1 290 128 112 117 120 1958 KC-AL 141 .305 515 93 157 20 7 38 104 50 82 3 1974 Chi-AL 12-15 0 4.70 38 35 10 1 216.1 230 128 113 110 102 1959 KC-AL 125 .285 463 61 132 22 4 20 87 35 87 3 1975 Chi-AL 4-6 0 6.01 12 12 2 0 67.1 -

North Atlantic Regional Business Law Association

Published by Husson University Bangor, Maine For the NORTH ATLANTIC REGIONAL BUSINESS LAW ASSOCIATION EDITORS IN CHIEF William B. Read Husson University Marie E. Hansen Husson University BOARD OF EDITORS Robert C. Bird Gerald A. Madek University of Connecticut Bentley University Gerald R. Ferrera Carter H. Manny Bentley University University of Southern Maine Stephanie M. Greene Christine N. O’Brien Boston College Boston College William E. Greenspan Lucille M. Ponte University of Bridgeport Florida Coastal School of Law Anne-Marie G. Hakstian Margo E.K. Reder Salem State College Boston College Chet Hickox Patricia Q. Robertson University of Rhode Island Arkansas State University Stephen D. Lichtenstein David Silverstein Bentley University Suffolk University David P. Twomey Boston College i GUIDELINES FOR 2011 Papers presented at the 2011 Annual Meeting and Conference will be considered for publication in the Business Law Review. In order to permit blind refereeing of manuscripts, papers must not identify the author or the author’s institutional affiliation. A removable cover page should contain the title, the author’s name, affiliation, and address. If you are presenting a paper and would like to have it considered for publication, you must submit two clean copies, no later than March 29, 2011 to: Professor William B. Read Husson University 1 College Circle Bangor, Maine 04401 The Board of Editors of the Business Law Review will judge each paper on its scholarly contribution, research quality, topic interest (related to business law or the legal environment of business) writing quality, and readiness for publication. Please note that, although you are welcome to present papers relating to teaching business law, those papers will not be eligible for publication in the Business Law Review. -

The Official Magazine of Angels Baseball

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF ANGELS BASEBALL JESSE MAGAZINE CHAVEZ VOL. 14 / ISSUE 2 / 2017 $3.00 CAMERON DANNY MAYBIN ESPINOSA MARTIN MALDONADO FRESH FACES WELCOME TO THE ANGELS TABLE OF CONTENTS BRIGHT IDEA The new LED lighting system at Angel Stadium improves visibility while reducing glare and shadows on the field. THETHE OFFICIALOFFICCIAL GAMEGA PUBLICATION OF ANGELS BASEBALL VOLUME 14 | ISSUE 2 WHAT TO LOOK FORWARD TO IN THIS ISSUE 5 STAFF DIRECTORY 43 MLB NETWORK PRESENTS 71 NUMBERS GAME 109 ARTE AND CAROLE MORENO 6 ANGELS SCHEDULE 44 FACETIME 75 THE WRIGHT STUFF 111 EXECUTIVES 9 MEET CAMERON MAYBIN 46 ANGELS ROSTER 79 EN ESPANOL 119 MANAGER 17 ELEVATION 48 SCORECARD 81 FIVE QUESTIONS 121 COACHING STAFF 21 MLB ALL-TIME 51 OPPONENT ROSTERS 82 ON THE MARK 127 WINNINGEST MANAGERS 23 CHASING 3,000 54 ANGELS TICKET INFORMATION 84 ON THE MAP 128 ANGELS MANAGERS ALL-TIME 25 THE COLLEGE YEARS 57 THE BIG A 88 ON THE SPOT 131 THE JUNIOR REPORTER 31 HEANEY’S HEADLINES 61 ANGELS 57 93 THROUGH THE YEARS 133 THE KID IN ME 34 ANGELS IN BUSINESS COMMUNITY 65 ANGELS 1,000 96 FAST FACT 136 PHOTO FAVORITES 37 ANGELS IN THE COMMUNITY 67 WORLD SERIES WIN 103 INTRODUCING... 142 ANGELS PROMOTIONS 41 COVER BOY 68 ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT 105 MAKING THE (INITIAL) CUT 144 FAN SUPPORT PUBLISHED BY PROFESSIONAL SPORTS PUBLICATIONS ANGELS BASEBALL 519 8th Ave., 25th Floor | New York, NY 10018 2000 Gene Autry Way | Anaheim, CA 92806 Tel: 212.697.1460 | Fax: 646.753.9480 Tel: 714.940.2000 facebook.com/pspsports twitter.com/psp_sports facebook.com/Angels @Angels ©2017 Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. -

2018 Media Guide.Indd

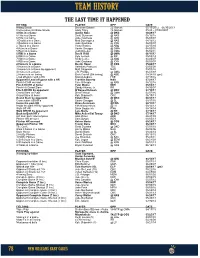

team history the last time it happened HITTING PLAYER OPP DATE Hitting Streak Donovan Solano 22 Games 05/13/2012 – 06/30/2013 Consecutive On Base Streak Andy Tracy 43 Games 05/23 – 07/08/2007 4 Hits in a Game Austin Nola @ OKC 08/29/17 5 Hits in a Game Scott Sizemore @ NAS 05/16/15 6 Hits in a Game Jake Gautreau @ IOW 06/09/07 3 Doubles in a Game Matt Dominguez @ NAS 04/16/12 4 Doubles in a Game Jake Gautreau @ IOW 06/09/07 2 Triples in a Game Vinny Rottino @ ABQ 04/15/10 4 Runs in a Game Xavier Scruggs @ OMA 04/09/16 5 Runs in a Game Josh Kroeger @ OMA 06/02/11 5 RBI in a Game David Vidal @ OMA 06/11/17 6 RBI in a Game Kyle Jensen @ RR 05/05/14 7 RBI in a Game Ricky Ledee @ ABQ 04/24/07 8 RBI in a Game Jake Gautreau @ IOW 06/09/07 2 Homers in a Game Destin Hood @ COS 05/24/17 3 Homers in a Game Valentino Pascucci TUC 08/02/08 3 Homers in a Game by opponent Matt Chapman NAS 09/03/16 4 Homers in a Game J.R. Phillips @ OMA 05/21/97 2 Homers in an Inning Brett Carroll (5th inning) @ ABQ 08/24/10 gm2 Lead off game with a HR Robert Andino FRE 07/15/16 Opponent Lead off game with a HR Franklin Barreto NAS 07/21/17 Pinch Hit HR on road Cole Gillespie @ IOW 04/12/16 Pinch Hit HR at home Tyler Moore IOW 05/02/17 Pinch Hit Grand Slam Sandy Alomar, Jr. -

General Information ...1-11

GENERAL INFORMATION .............................................. 1-11 Table of Contents........................................................................................1 2021 Quick Facts........................................................................................2 2021 Schedule............................................................................................3 Roster and Pronunciation Guide .............................................................4-5 Media and Fan Information......................................................................6-7 Hawks Field at Haymarket Park ............................................................8-11 2021 HUSKERS ................................................................12-47 Returners .............................................................................................12-43 Newcomers..........................................................................................44-47 COACHES AND STAFF ...............................................48-57 Head Coach Will Bolt...........................................................................48-49 Assistant Coach Lance Harvell.................................................................50 Assistant Coach Jeff Christy .....................................................................51 Volunteer Assistant Coach Danny Marcuzzo............................................52 Director of Operations Curtis Ledbetter ....................................................53 Director of Player Development -

Baseball) Rule R

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Health, Exercise, and Sports Sciences ETDs Education ETDs 9-5-2013 PLAYING HARDBALL: AN ANALYSIS OF COURT DECISIONS INVOLVING THE LIMITED DUTY (BASEBALL) RULE R. Douglas Manning Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/educ_hess_etds Recommended Citation Manning, R. Douglas. "PLAYING HARDBALL: AN ANALYSIS OF COURT DECISIONS INVOLVING THE LIMITED DUTY (BASEBALL) RULE." (2013). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/educ_hess_etds/30 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Education ETDs at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Health, Exercise, and Sports Sciences ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. R. Douglas Manning Candidate Department of Health, Exercise and Sport Sciences Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Annie Clement, J.D. , Chairperson Dr. Todd Seidler Dr. John Barnes Gil Fried, Esq. Dr. Glenn Hushman i PLAYING HARDBALL: AN ANALYSIS OF COURT DECISIONS INVOLVING THE LIMITED DUTY (BASEBALL) RULE by R. DOUGLAS MANNING B.S. Social Science Education, Florida State University, 2002 M.S. Sport Administration, Florida State University, 2003 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Physical Education, Sports, & Exercise Science The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2013 ii DEDICATION Mi Amor . 私の妻 My best friend and the mother of our daughter. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dr. Clement, J.D., my mentor, friend, professor, and committee chair. From our days together at Florida State University to the University of New Mexico, thank you for the immense impact you have had on my educational pursuits. -

The Official Magazine of Angels Baseball Magazine

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF ANGELS BASEBALL MAGAZINE VOL. 14 / ISSUE 5 / 2017 $3.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS COWBOY UP THE OFFICIALAL GAMEGAME PUBLICATIONPUBLICATION OFOF ANGELSANNGGEEL BASEBALL VOLUME 14 | ISSUE 5 WHAT TO LOOK FORWARD TO IN THIS ISSUE 5 IN MEMORY, DON BAYLOR 47 FACETIME 90 LOOKING TOWARDS THE FUTURE 133 ON THE MARK 8 STAFF DIRECTORY 51 ANGELS ROSTER 93 COLLEGE BALL 135 EN ESPAÑOL 10 ANGELS SCHEDULE 54 SCORECARD 97 ARTE AND CAROLE MORENO 136 FIVE QUESTIONS 13 PATH TO COOPERSTOWN 57 OPPONENT ROSTERS 99 EXECUTIVES 139 FAST FACT 21 ANGELS IN THE COMMUNITY 60 ANGELS TICKET INFORMATION 107 MANAGER 145 ON THE SPOT 24 PUJOLS GOLF 63 THE BIG A 109 ALL-TIME MANAGERS WINS 147 HEART AND HUSTLE 27 FOX FOCUS 67 THE WRIGHT STUFF 111 THE SIMPSONS/MIKE SCIOSCIA 149 THE KID IN ME 32 FATHER AND SON 73 WORLD SERIES WIN 115 COACHING STAFF 150 THE JUNIOR REPORTER 34 THROUGH THE YEARS 77 A LOOK BACK 119 PITCHING IN 152 ‘GET YOUR ANGEL MAGAZINE!’ 37 PATH TO THE BIG LEAGUES 81 THE FLYING DUTCHMAN 122 POMONA AND THE PROS 155 GIVEAWAYS/EVENTS 41 2017 MILESTONES 85 POPULAR NUMBER 125 ANGELS BATTING PRACTICE 156 THANK YOU 44 ANGELS IN THE BUSINESS 86 ONE AND DONE 129 HONORED ALUM COMMUNITY 89 FISH OUT OF WATER 131 ON THE MAP PUBLISHED BY PROFESSIONAL SPORTS PUBLICATIONS ANGELS BASEBALL 519 8th Ave., 25th Floor | New York, NY 10018 2000 Gene Autry Way | Anaheim, CA 92806 Tel: 212.697.1460 | Fax: 646.753.9480 Tel: 714.940.2000 facebook.com/pspsports twitter.com/psp_sports facebook.com/Angels @Angels ©2017 Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. -

36 Huskers Have Played in a Major League Baseball Game 9 World Series Rings • 9 All-Star Selections • 10 Gold Glove Awards

HUSKERS IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL 36 Huskers have played in a Major League Baseball Game 9 World Series Rings • 9 All-Star Selections • 10 Gold Glove Awards BOB CERV (PLAYED AT NEBRASKA: 1947-50) STAN BAHNSEN (PLAYED AT NEBRASKA: 1965) MLB Career: 1951-62 MLB Career: 1966-82 Kansas City Athletics, New York Yankees, Los Angeles Angels, Houston Astros New York Yankees, Chicago White Sox, Oakland Athletics, Montreal Expos, California Angels, Philadelphia Phillies Honors World Series Champion (1956) Honors All-Star (1958) American League Rookie of the Year (1968) Year Team G AVG AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO SB Year Team W-L SV ERA G GS CG SH IP H R ER BB SO 1951 NY-AL 12 .214 28 4 8 1 0 0 2 4 6 0 1966 NY-AL 1-1 1 3.52 4 3 1 0 23 15 9 9 7 16 1952 NY-AL 36 .241 87 11 21 3 2 1 8 9 22 0 1968 NY-AL 17-12 0 2.05 37 34 10 1 267.1 216 72 61 68 162 1953 NY-AL 8 .000 6 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1969 NY-AL 9-16 1 3.83 40 33 5 2 220.2 222 102 94 90 130 1954 NY-AL 56 .260 100 14 26 6 0 5 13 11 17 0 1970 NY-AL 14-11 0 3.33 36 35 6 2 232.2 227 100 86 75 116 1955 NY-AL 55 .341 85 17 29 4 2 3 22 7 16 4 1971 NY-AL 14-12 0 3.35 36 34 14 3 242 221 99 90 72 110 1956 NY-AL 54 .304 115 16 35 5 6 3 25 18 13 0 1972 Chi-AL 21-16 0 3.60 43 41 5 1 252.1 263 107 101 73 157 1957 KC-AL 124 .272 345 35 94 14 2 11 44 20 57 1 1973 Chi-AL 18-21 0 3.57 42 42 14 4 282.1 290 128 112 117 120 1958 KC-AL 141 .305 515 93 157 20 7 38 104 50 82 3 1974 Chi-AL 12-15 0 4.70 38 35 10 1 216.1 230 128 113 110 102 1959 KC-AL 125 .285 463 61 132 22 4 20 87 35 87 3 1975 Chi-AL 4-6 0 6.01 12 12 2 0 67.1 -

Edward C. V. City of Albuquerque: the New Mexico Supreme Court Balks on the Baseball Rule

Volume 41 Issue 2 Fall Fall 2011 Edward C. v. City of Albuquerque: The New Mexico Supreme Court Balks on the Baseball Rule Christopher McNair Recommended Citation Christopher McNair, Edward C. v. City of Albuquerque: The New Mexico Supreme Court Balks on the Baseball Rule, 41 N.M. L. Rev. 539 (2011). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol41/iss2/9 This Student Note is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr \\jciprod01\productn\N\NMX\41-2\NMX205.txt unknown Seq: 1 24-JAN-12 10:46 EDWARD C. V. CITY OF ALBUQUERQUE: THE NEW MEXICO SUPREME COURT BALKS ON THE BASEBALL RULE Christopher McNair* INTRODUCTION Baseball and litigation—arguably two of America’s greatest pas- times. Throughout baseball’s history, injuries to both players and specta- tors have been as common and accepted as home runs and the seventh inning stretch. Foul balls routinely enter the stands traveling nearly 100 miles an hour.1 Some estimate that in the course of an average profes- sional baseball game, thirty-five to forty baseballs are hit into spectator areas.2 While it is true that where injury exists, litigation may soon follow, baseball stadium owners/occupiers (Stadium Operators) have tradition- ally been granted a generous immunity from liability for spectator inju- ries resulting from projectiles leaving the field of play.3 In recent decades, however, courts have retreated from this traditional stance albeit without completely abandoning limitations on stadium operator liability.