RT& Essays on ART from a Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

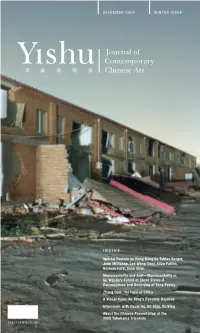

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

Annual Report 2015 Annual Report 2015

C h i na Air c ra f t L ea si n g G r o u p Ho l d i n gs Li mite d FULL VALUE-CHAIN AIRCRAFT SOLUTION PROVIDER www.calc.com.hk ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 REPORT ANNUAL (Incorporated under the laws of the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock code : 01848 ck.ng 04832_E01_IFC+Content_4C Time/date: 08-04-2016_06:18:53 China Aircraft Leasing Group Holdings Limited CALC AT A GLANCE 65 107 172 Aircraft fleet Aircraft on order with Aircraft in 2022 (as at 22 Mar 2016) Airbus (as at 22 Mar 2016) 3.5yrs 10yrs Over 20% Average fleet age Average remaining Market share of Airbus (as at 31 Dec 2015) lease term A320 series aircraft deliveries in China market in 2015 A constituent stock of the HK$23.9b 1st MSCI Listed aircraft lessor China Small Cap Total assets in Asia (as at 31 Dec 2015) Index A constituent stock of the Hang Seng Over 110 Global Composite Index Staff with 9 offices and the Hang Seng worldwide Composite Index 2 ck.ng 04832_E01_IFC+Content_4C Time/date: 08-04-2016_06:18:53 Annual Report 2015 CONTENTS 13 Company Profile 14 Financial Highlights and Five-Year Financial Summary 16 Major Achievements 18 Chairman Statement 21 Management Discussion and Analysis 29 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 49 Corporate Governance Report 59 Report of the Directors 74 Profile of the Directors and Senior Management 81 Independent Auditor's Report 83 Consolidated Balance Sheet 84 Consolidated Statement of Income 85 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 86 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 88 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 89 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 163 Corporate Information 1 ck.ng 04832_E02_All Divider+company profile_4C Time/date: 08-04-2016_06:18:53 China Aircraft Leasing Group Holdings Limited LEADING THE WAY CALC is a pioneer and a market leader in China’s aircraft leasing industry. -

Item for Finance Committee

For discussion FCR(2013-14)23 on 21 June 2013 ITEM FOR FINANCE COMMITTEE HEAD 95 – LEISURE AND CULTURAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT New Subhead “Acquiring and Commissioning Artworks by Local Artists” New Item “Acquiring and Commissioning Artworks by Local Artists” Members are invited to approve a new commitment of $50 million under a new subhead to be created under Head 95 Leisure and Cultural Services Department for acquiring and commissioning artworks by local artists. PROBLEM To foster the development of visual arts and nurture local artistic talent in the field, we need to provide additional funding for acquiring and commissioning more artworks by local artists. PROPOSAL 2. The Director of Leisure and Cultural Services (DLCS), with the support of the Secretary for Home Affairs (SHA), proposes to create a new commitment of $50 million for the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) to acquire and commission artworks by local artists. JUSTIFICATION 3. It is the Government’s cultural policy to develop Hong Kong into an international cultural metropolis. To achieve this policy objective, LCSD has been making continued efforts in nurturing artistic talent. To strengthen the development of visual arts and groom local artists in the area of visual arts, we consider it important to provide artists with opportunities to showcase their artworks on a frequent and continual basis. One of the most effective means is to acquire their /artworks ….. FCR(2013-14)23 Page 2 artworks and display them in our public museums, and commission their artworks for public arts projects. This could help promote their profile and build their audience, which provides a solid basis for their development in the arts sector. -

Art Market Trends Tendances Du Marché De L'art

Art market trends Tendances du marché de l'art THE WORLD LEADER IN ART MARKET INFORMATION Art market trends Tendances du marché de l'art 2005 $ 4.15 billion (€ 3.38 billion) 3.38 (€ billion 4.15 $ worldwide: auctions Art Fine at Turnover offer. on lots 320,000 of volume stable practically billion, vs. 3.6 $ billion the previous year, In despite 2005 the a turnover for record-breaking! Fine are gures Art sales fi The exceeded 4 $ well. so performed never has market art international The a million dollars, compared with compared in only 393 2004 dollars, a and million than more for hammer the under went lots 477 than less into of a rise sales 1 multiplication $ exceeding No million 19% the from translated ation on in recorded infl 2004. price This following already year, last 10.4%* of increase came on the of back a progression price incredible This Tendances du marché de l'art de marché du Tendances Art market trends trends market Art Artprice Global Index: Paris - New York - London (1994 - 2005) Base January 1994 = 100 - Quarterly data Artprice Indices are calculated with the Repeated Sales method (Econometric calculations on sales/resales of similar works) 10 000 $, 10 et 56% en deçà de 000 $.2 Ce segment est en 2005 en publiques ventes ont adjugés été moins de cette cette année, faisant suite aux d’affaires 19% mondial, de une hausse élévation déjà des A prix l’origine de de cette 10,4% incroyable progression du chiffre (3,38 d’euro) dollars de milliards milliards 4,15 : mondiales enchères Artaux Fine de ventes des Produit présentés. -

Convergence of the Practices of Documentary and Contemporary Art in Hong Kong: Autoethnographic Works of Tang Kwok Hin and Law Yuk Mui

REPORT CONVERGENCE OF THE PRACTICES OF DOCUMENTARY AND CONTEMPORARY ART IN HONG KONG: AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC WORKS OF TANG KWOK HIN AND LAW YUK MUI Hoi Shan Anson Mak, Hong Kong Baptist University ABSTRACT This article is part of a research project funded by the University Grants Committee, Hong Kong. The project title is ‘Convergence of Documentary Practices in Contemporary Arts in Hong Kong’. We collected 230 artworks from 31 artists/artist groups for textual analysis. Twelve artists were selected for a focus study and interviews. Eleven short edited interviews with English subtitles, together with information on the artworks and artists, are freely available online to anyone, especially researchers and teachers, interested in using the materials for their own projects. There are also artworks (with artists’ permission) that go with artists interview, hence audience can better comprehend when artists referring to their artworks. URL: https://docuarthk.wixsite.com/research/artists-n-z Among many findings, autoethnography is shown to anchor an interesting point of intersection across disciplines. This article explores autoethnography, originally applied as a qualitative research method, echoes with the practices in reflexive documentary and the ways being used by contemporary visual artists in Hong Kong. This writing examines autoethnographic artworks by Tang Kwok Hin and Law Yuk Mui regarding notion of homes and relational autoethnographic subjectivities. KEYWORDS Autoethnography, Home, Hong Kong Contemporary Arts, Experimental Ethnography BIO Anson Mak is a researcher-artists, specialized in moving image and sound. She currently works as Associate Professor in Academy of Visual Arts in Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong. She is especially interested in experimental ethnography and manipulation of super 8 film in the digital era. -

Issue 5 • Winter 2021 5 Winter 2021

Issue 5 • Winter 2021 5 winter 2021 Journal of the school of arts and humanities and the edith o'donnell institute of art history at the university of texas at dallas Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 185 11/6/20 1:24 PM 2 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 2 11/6/20 1:23 PM 1 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 1 11/6/20 1:23 PM This issue of Athenaeum Review is made possible by a generous gift from Karen and Howard Weiner in memory of Richard R. Brettell. 2 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 2 11/6/20 1:23 PM Athenaeum Review Athenaeum Review publishes essays, reviews, Issue 5 and interviews by leading scholars in the arts and Winter 2021 humanities. Devoting serious critical attention to the arts in Dallas and Fort Worth, we also consider books and ideas of national and international significance. Editorial Board Nils Roemer, Interim Dean of the School of Athenaeum Review is a publication of the School of Arts Arts and Humanities, Director of the Ackerman and Humanities and the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Center for Holocaust Studies and Stan and Art History at the University of Texas at Dallas. Barbara Rabin Professor in Holocaust Studies School of Arts and Humanities Dennis M. Kratz, Senior Associate Provost, Founding The University of Texas at Dallas Director of the Center for Asian Studies, and Ignacy 800 West Campbell Rd. JO 31 and Celia Rockover Professor of the Humanities Richardson, TX 75080-3021 Michael Thomas, Director of the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History and Edith O’Donnell [email protected] Distinguished University Chair in Art History athenaeumreview.org Richard R. -

Creative Arts Space in Hong Kong: Three Tales Through the Lens of Cultural Capital

c Creative Arts Space in Hong Kong: Three Tales through the lens of Cultural Capital Hoi Ling Anne CHAN (0000-0002-8356-8069) A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning University of Melbourne February 2019 [Intended to leave blank] i Abstract The fact that culture and creativity are often instrumentalised in urban regeneration and/or development points to a pragmatic relationship between culture and the city. Hong Kong, like many post-colonial and post-industrial cities, faced challenges in economic restructuring and in the search of a new identity. Thus, culture came to the centre of the stage in the formulation of development strategies and started to accumulate cultural assets. The accumulation of cultural assets led to the emergence of various forms of cultural assets such as cultural district, infrastructure, projects in order to achieve various aims. However, most of the existing research focused on large-scale flagship projects from an economic or strategic perspective. A holistic understanding of those cultural projects is limited in the literature especially for the small-scale cultural projects. This research examines how the creative arts spaces interact with the host city, Hong Kong through the lens of cultural capital. Three creative arts spaces with different management models are chosen as case studies. Data were collected through field investigation and key informant interviews as well as from secondary sources such as archives and media. The data collected are analysed by executing thematic analysis procedures. The findings reveal that creative arts spaces are different from large-scale flagship projects in their relations to cities. -

Reflections on Anonymity and Contemporaneity in Chinese Art Beatrice Leanza

PLACE UNDER THE LINE PLACE UNDER THE LINE : july / august 1 vol.9 no. 4 J U L Y / A U G U S T 2 0 1 0 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4 INSIDE New Art in Guangzhou Reviews from London, Beijing, and San Artist Features: Gu Francisco Wenda, Lin Fengmian, Zhang Huan The Contemporary Art Academy of China Identity Politics and Cultural Capital in Contemporary Chinese Art US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4, JULY/AUGUST 2010 CONTENTS 2 Editor’s Note 33 4 Contributors 6 The Guangzhou Art Scene: Today and Tomorrow Biljana Ciric 15 On Observation Society Anthony Yung Tsz Kin 20 A Conversation with Hu Xiangqian 46 Biljana Ciric, Li Mu, and Tang Dixin 33 An interview with Gu Wenda Claire Huot 43 China Park Gu Wenda 46 Cubism Revisited: The Late Work of Lin Fengmian Tianyue Jiang 63 63 The Cult of Origin: Identity Politics and Cultural Capital in Contemporary Chinese Art J. P. Park 73 Zhang Huan: Paradise Regained Benjamin Genocchio 84 Contemporary Art Academy of China: An Introduction Christina Yu 87 87 Of Jungle—In Praise of Distance: Reflections on Anonymity and Contemporaneity in Chinese Art Beatrice Leanza 97 Shanghai: Art of the City Micki McCoy 104 Zhang Enli Natasha Degan 97 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Zhang Huan, Hehe Xiexie (detail), 2010, mirror-finished stainless steel, 600 x 420 x 390 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Vol.9 No.4 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art president Katy Hsiu-chih Chien legal counsel Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C.C. -

Unified Style

8 L a c k i n g a u n i fi e d s t y l e Note: you are reading an excerpt from: James Elkins, “Failure in Twentieth-Century Painting” (unpublished MS) Revised 9.2001 This page was originally posted on: www.jameselkins.com Send all comments to: [email protected] A painter who lacks all style, who is compelled to mimic others, is unoriginal: the subject of Chapter 3. It is a different matter to be unable to find a voice, a manner, or a consistent approach, so that it’s necessary work work by cobbling together different styles. Stylistic mixture was frequently a deliberate strategy in twentieth-century painting, for example in cubist collage, dada, surrealism, pop art, and some postmodernism: but in the majority of cases a lack of unity remains the inevitable sign of beginner’s painting. When a student painter hasn’t found a voice, she will try different things, sampling one and then another, until eventually (hopefully, in graduate school) something emerges that ties the work together, and a unified style emerges—it’s a mysterious accomplishment, one that is not prone to clear analysis.1 Outside the West, lack of unified style is a serious problem, not only because intentionally disunified styles such as surrealism tend to be less popular, but because each artist has to face the problem of bringing their own country’s art into some reapprochement with aspects of Western painting. In this chapter I consider disunified painting in several regions of Asia: China, India, Japan, and the Central Asian Republics. -

LC Paper No. CB(2)802/12-13(05)

LC Paper No. CB(2)802/12-13(05) For information on 22 March 2013 Legislative Council Panel on Home Affairs Measures to Enhance Public Museum Services Purpose This paper updates Members on the progress made to enhance the services of public museums under the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD). Progress Made on Enhancement of Public Museum Services 2. There are 14 public museums1 being managed by LCSD. Since 2010, LCSD has set eight new directions for museum development with the aim of delivering museum services with greater transparency, accountability, efficiency and creativity so as to meet the changing aspirations of the community. 3. With the expert advice given by museum advisors and the concerted efforts of museum staff, many of the programmes organised by the museums in the past few years have received overwhelming response, as evident from the record breaking attendance of 5.8 million visitors and 1.17 million people taking part in the education and extension programmes organised by the museums in 2012. The new directions set for the museums and the progress made in the past three years (2010-2012) are summarised in the ensuing paragraphs. (a) Enhancing Public Accountability and Transparency (i) Museum Advisory Panels 4. To enhance public accountability and involvement in the management of museums, three Museum Advisory Panels (MAPs) for the Art, History and Science 1 The 14 museums are Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong Museum of History, Hong Kong Heritage Museum, Hong Kong Science Museum, Hong Kong Space Museum, Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware, Dr Sun Yat-sen Museum, Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence, Fireboat Alexander Grantham Exhibition Gallery, Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb Museum, Law Uk Folk Museum, Sam Tung Uk Museum, Hong Kong Railway Museum and Sheung Yiu Folk Museum. -

Proposed Museum Expert Advisers for 2006/07

Museum Expert Advisers (1 April 2020 to 31 March 2022) Museum expert advisers are appointed by the Director of Leisure and Culture Services for a period of two years to provide professional advice to the museums of the Leisure and Cultural Services Department on matters pertaining to the promotion of art, history, science and film, in particular the acquisition of collection items. Advisers specialising in the field of art and history are as follows: (Names are listed in alphabetical order) Art Name Professional Background Hong Kong Art The late Mr Gaylord Co-founder and first Chairman, Hong Kong Visual Arts CHAN, MBE, BBS Society (1974) Co-founder, Culture Corner Art Academy (1989) Co-founder, Artmatch Group (1995) Prof CHAN Yuk Adjunct Professor, Department of Fine Arts, The Chinese Keung University of Hong Kong Prof CHANG Ping Architect Hung, Wallace Chairman, 1a space Associate Professor, Department of Architecture, The University of Hong Kong Prof David CLARKE Honorary Professor, Department of Fine Arts, The University of Hong Kong Dr Anissa FUNG Former Associate Professor, The Education University of Hong Kong Ceramic Artist Products Design and Development Consultant Mr FUNG Ho Yin Visiting Lecturer, School of Design, Hong Kong Polytechnic University Chairman, Hong Kong Open Printshop Mr FUNG Hon Kee, Programme Leader/ Lecturer, Postgraduate Diploma in Joseph Photography, HKU School of Professional and Continuing Education Honorary Advisor and Founding Member, Hong Kong Photographic Culture Association - Name Professional