Xay Temíxw Land Use Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuesday, June 20,2000 the Chief W Squamish, BC

Tuesday, June 20,2000 The Chief W Squamish, B.C. Bits & Pieces Weather Watch ! i Upcoming issues for the June 20 meeting of council at 7 p.m. in council chambers at Municipal Hall: Council will consider authorizing the transfer of the Baldwin Steam Locomotive 2-6-2, known as the Pacific GRa lhesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Eastern’s WoSpot, to the West Coast Railway Association for $1, ending a lease to the WCRA begun in 1991. BS roa Sunny wit ti Chance of Sunny with A mixture of Council will consider issuing a two-year industrial use permit to Canadian Occidental Petroleum for 35001 Galbrait1 Br cloudy periods. sun and cloud- cloudy periods. showers. Ave. for temporary waste storage cells to store and treat contaminate soils. Schl Low 10. Low 12. Low 11. Low 11. to 1 High 26. High 23. High 22. High 19. Council will consider approval of the new ice allocation policy and user group dispute resolution policy for the rec~ awa ation services department. Di The Moon !akil jc hc ias No discussion by council on -oad 3.w AV itart retusina service to enviro aro.uas Ned New Moon First Quarter Full Moon Last Quarter U 0000 For the record, The Chief Ujjal Dosanjh and various gal protests. an audience member th July 1 July 8 July 16 June 24 :hu would like to clarify motions ministries. Council also voted to inves- some northern communitil passed at the June 8 special Council also passed a tigate taking over the con- have created a Greenpea0 ;pel Rc: council meeting mentioned in motion condemning the ille- struction of the Elaho to free zone, which includt The Tides last week’s story “Protesters gal actions of protesters and Meagher Creek trail fiom the refusing gas, hotel, servia t ten not welcome in Squamish.” demanding the province force Western Canada Wilderness etc. -

Section 12.0: Aborigin Al Consultation

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT CERTIFICATE APPLICATION WesPac Tilbury Marine Jetty Project ABORIGINAL ABORIGINAL : 0 . 12 CONSULTATION SECTION SECTION WesPac Tilbury Marine Jetty Project Environmental Assessment Certificate Application Part C – Aboriginal Consultation Section 12.0: Aboriginal Consultation 12.0 ABORIGINAL CONSULTATION Aboriginal Interests are defined in the Section 11 Order (BCEAO, 2015b) as asserted or determined Aboriginal rights, including title, and treaty rights. An overview of planned consultation activities for the Project, activities completed to date, and a description of Aboriginal Interests is provided in Section 12.1 Aboriginal Interests. The assessment of Project-related effects on those Aboriginal Interests is presented in Section 12.1.4 Potential Effects of the Project on Aboriginal Interests. Issues raised by Aboriginal groups that do not directly relate to Aboriginal Interests, such as those pertaining to potential adverse social, economic, heritage, or health effects, and proposed measures to address those effects, are described in Section 12.2 Other Matters of Concern to Aboriginal groups. The assessment of effects on Other Matters of Concern to Aboriginal groups is also found in Section 12.2 Other Matters of Concern to Aboriginal groups. Section 12.3 provides the Issue Summary Table that summarizes Aboriginal Interests or other matters of concern to Aboriginal groups that may be affected by the Project, and the measures to avoid, mitigate or otherwise manage those effects. Information presented in this Application -

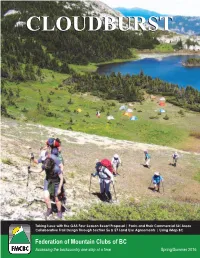

Cloudburstcloudburst

CLOUDBURSTCLOUDBURST Taking Issue with the GAS Four Season Resort Proposal | Parks and their Commercial Ski Areas Collaborative Trail Design Through Section 56 & 57 Land Use Agreements | Using iMap BC Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Accessing the backcountry one step at a time Spring/Summer 2016 CLOUDBURST Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Published by : Working on your behalf Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC PO Box 19673, Vancouver, BC, V5T 4E7 The Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC (FMCBC) is a democratic, grassroots organization In this Issue dedicated to protecting and maintaining access to quality non-motorized backcountry rec- reation in British Columbia’s mountains and wilderness areas. As our name indicates we are President’s Message………………….....……... 3 a federation of outdoor clubs with a membership of approximately 5000 people from 34 Recreation & Conservation.……………...…… 4 clubs across BC. Our membership is comprised of a diverse group of non-motorized back- Member Club Grant News …………...………. 11 country recreationists including hikers, rock climbers, mountaineers, trail runners, kayakers, Mountain Matters ………………………..…….. 12 mountain bikers, backcountry skiers and snowshoers. As an organization, we believe that Club Trips and Activities ………………..…….. 15 the enjoyment of these pursuits in an unspoiled environment is a vital component to the Club Ramblings………….………………..……..20 quality of life for British Columbians and by acting under the policy of “talk, understand and Some Good Reads ……………….…………... 22 persuade” we advocate for these interests. Garibaldi 2020…... ……………….…………... 27 Membership in the FMCBC is open to any club or individual who supports our vision, mission Executive President: Bob St. John and purpose as outlined below and includes benefits such as a subscription to our semi- Vice President: Dave Wharton annual newsletter Cloudburst, monthly updates through our FMCBC E-News, and access to Secretary: Mack Skinner Third-Party Liability insurance. -

Squamish Community: Our People and Places Teacher’S Package

North Vancouver MUSEUM & ARCHIVES SCHOOL PROGRAMS 2018/19 Squamish Community: Our People and Places Teacher’s Package Grade 3 - 5 [SQUAMISH COMMUNITY: OUR PEOPLE AND PLACES KIT] Introduction SQUAMISH COMMUNITY: OUR PEOPLE AND PLACES KIT features 12 archival photographs selected from the Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw: The Squamish Community: Our People and Places exhibit presented at the North Vancouver Museum & Archives in 2010. This exhibit was a collaborative project undertaken by the North Vancouver Museum & Archives and the Squamish Nation. These archival images were selected by the Squamish Elders and Language Authority to represent local landscapes, the community and the individual people within the Squamish Nation. The Squamish Elders and Language Authority also contributed to the exhibit labels which are included on the reverse of each picture. This Kit has been designed to complement BC’s Social Studies curriculum for grades 3 - 5, giving students the opportunity to explore themes related to First Nations cultures in the past and cultural First Nations activities today. Included within this Kit is a detailed teacher’s package that provides instructors with lesson plan activities that guide students in the analysis of archival photographs. The recommended activities encourage skills such as critical thinking and cooperative learning. Altogether, the lesson plan activities are estimated to take 1 hour and 45 minutes and can easily be stretched across several instructional days. Through photo analysis worksheets and activities, students will be introduced to the Squamish Nation and historical photographs. Teachers are encouraged to read through the program and adapt it to meet the learning abilities and individual needs of their students. -

Aboriginal Knowledge and Ecosystem Reconstruction

Back to the Future in the Strait of Georgia, page 21 PART 2: CULTURAL INPUTS TO THE STRAIT OF GEORGIA ECOSYSTEM RECONSTRUCTION BTF project was based on archival research and Aboriginal Knowledge and interviews with Elders from Aboriginal Ecosystem Reconstruction communities. The main purpose of the interviews was to frame a picture of how the ecosystem might have been in the past, based on traditional Silvia Salas, Jo-Ann Archibald* knowledge of resource use by aboriginal people. & Nigel Haggan This information was expected to validate and complement archival information was also Fisheries Centre, UBC describing the state of past natural system. *First Nations House of Learning, UBC Methods The BTF project involved the reconstruction of Abstract present and past ecosystems in the Strait of Georgia (SoG), based on a model constructed at a The ‘Back To The Future’ (BTF) project uses workshop held in November 1995 at the Fisheries ecosystem modelling and other information Centre, the University of British Columbia, sources to visualize how the Strait of Georgia Canada (Pauly and Christensen, 1996). Different ecosystem might have been in the past. This sources of information (see Wallace, this vol.) paper explores the potential of integrating were used to tune and update that model. traditional environmental knowledge (TEK) of Reconstruction of the system as it might have aboriginal people in ecosystem modeling. been 100 ago was based on archival records, Methods include archival research and interviews historic documents and written testimonies, as with First Nation Elders from different regions of well as interviews carried out in three First the Strait of Georgia. -

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver J EAN BARMAN1 anada has become increasingly urban. More and more people choose to live in cities and towns. Under a fifth did so in 1871, according to the first census to be held after Canada C 1867 1901 was formed in . The proportion surpassed a third by , was over half by 1951, and reached 80 percent by 2001.2 Urbanization has not benefited Canadians in equal measure. The most adversely affected have been indigenous peoples. Two reasons intersect: first, the reserves confining those deemed to be status Indians are scattered across the country, meaning lives are increasingly isolated from a fairly concentrated urban mainstream; and second, the handful of reserves in more densely populated areas early on became coveted by newcomers, who sought to wrest them away by licit or illicit means. The pressure became so great that in 1911 the federal government passed legislation making it possible to do so. This article focuses on the second of these two reasons. The city we know as Vancouver is a relatively late creation, originating in 1886 as the western terminus of the transcontinental rail line. Until then, Burrard Inlet, on whose south shore Vancouver sits, was home to a handful of newcomers alongside Squamish and Musqueam peoples who used the area’s resources for sustenance. A hundred and twenty years later, apart from the hidden-away Musqueam Reserve, that indigenous presence has disappeared. 1 This article originated as a paper presented to the Canadian Historical Association, May 2007. I am grateful to all those who commented on it and to Robert A.J. -

Council/School Board Liaison Committee

City of Richmond Minutes Council/School Board Liaison Committee Date: Wednesday, October 15,2014 Place: Anderson Room Richmond City Hall Present: Councillor Linda Barnes, Chair Councillor Linda McPhail Trustee Donna Sargent Trustee Norm Goldstein Also Present: Trustee Grace Tsang Call to Order: The Chair called the meeting to order at 9: 00 a.m. AGENDA It was moved and seconded That the Council/School Board Liaison Committee agenda for the meeting of Wednesday, October 15,2014, be adopted as circulated, with Item No.5 to be considered after Item No.2. CARRIED MINUTES It was moved and seconded That the minutes of the meeting of the Council/School Board Liaison Committee held on Tuesday, June 10,2014, be adopted as circulated. CARRIED CNCL - 68 1. Council/School Board Liaison Committee Wednesday, October 15, 2014 BUSINESS ARISING 1. GENERAL LOCAL ELECTION SOCIAL MEDIA PLAN (COR - David Weber, Ted Townsend, Justinne Ramirez) (Verbal Update) David Weber, Chief Elections Officer, provided an overview of the 2014 Election social media plan, which included the Richmond Election App, Twitter, Facebook, "Be a Voter Campaign" and the Candidate Voters Guide. Mr. Weber advised that the Richmond Election App is available to iPhone and Android users, and it displays key information such as who can vote, candidate profiles, and election results. Also, he stated that the "Be a Voter Campaign" is a series of advertisements targeted at encouraging citizens to vote on Election Day - November 15, 2014. Mr. Weber distributed copies of the advertisements (copy on file in the City Clerk's Office). Ted Townsend, Senior Manager, Corporate Communications, spoke on the Richmond Election App's significant media coverage, highlighting that it is one of a few in the province. -

Squamish Nation Direct Evidence

Hearing Order MH-052-2018 Board File: OF-Fac-Oil-T260-2013-03 59 NATIONAL ENERGY BOARD IN THE MATTER OF the National Energy Board Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. N-7, as amended (“NEB Act”) and the Regulations made thereunder; AND IN THE MATTER OF an application by Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC as General Partner of Trans Mountain Pipeline L.P. (collectively “Trans Mountain”) for a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity and other related approvals pursuant to Part III of the NEB Act for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project (“Project”); AND IN THE MATTER OF the National Energy Board’s reconsideration of aspects of its Recommendation Report (“Report”) as directed by the Governor in Council through Order in Council P.C. 2018-1177 (the “Reconsideration”). SQUAMISH NATION DIRECT EVIDENCE December 5, 2018 Introduction 1. The Squamish Nation (“Squamish” or the “Nation”) relies on and adopts the evidence that it provided to the National Energy Board (the “Board” or the “NEB”) in the OH-001- 2014 proceeding. The Nation references some of the information on the record in the OH-001-2014 proceeding below to highlight relevant aspects and to provide context for the evidence to be considered in the Reconsideration hearing. Squamish Nation 2. The Squamish Nation (“Squamish” or the “Nation”) is a Coast Salish Nation. Squamish is a self-identifying Aboriginal Nation and an Aboriginal people. We currently have over 4,053 registered members. 3. Since a time before contact with Europeans, Squamish have used and occupied lands and waters on the southwest coast of what is now British Columbia extending from the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, and including Burrard Inlet, English Bay, Howe Sound, the Squamish Valley and north to Whistler (the “Territory”). -

COAST SALISH SENSES of PLACE: Dwelling, Meaning, Power, Property and Territory in the Coast Salish World

COAST SALISH SENSES OF PLACE: Dwelling, Meaning, Power, Property and Territory in the Coast Salish World by BRIAN DAVID THOM Department of Anthropology, McGill University, Montréal March, 2005 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Brian Thom, 2005 Abstract This study addresses the question of the nature of indigenous people's connection to the land, and the implications of this for articulating these connections in legal arenas where questions of Aboriginal title and land claims are at issue. The idea of 'place' is developed, based in a phenomenology of dwelling which takes profound attachments to home places as shaping and being shaped by ontological orientation and social organization. In this theory of the 'senses of place', the author emphasizes the relationships between meaning and power experienced and embodied in place, and the social systems of property and territory that forms indigenous land tenure systems. To explore this theoretical notion of senses of place, the study develops a detailed ethnography of a Coast Salish Aboriginal community on southeast Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Through this ethnography of dwelling, the ways in which places become richly imbued with meanings and how they shape social organization and generate social action are examined. Narratives with Coast Salish community members, set in a broad context of discussing land claims, provide context for understanding senses of place imbued with ancestors, myth, spirit, power, language, history, property, territory and boundaries. The author concludes in arguing that by attending to a theorized understanding of highly local senses of place, nuanced conceptions of indigenous relationships to land which appreciate indigenous relations to land in their own terms can be articulated. -

Paper Applying Human Dimensions Theory Into Practice

GWS2013 abstracts as of January 2, 2013 • Listed alphabetically by lead author / organizer (Invited Papers Sessions grouped at end of file) Applying Human Dimensions Theory Into Practice: A Story of The 556th National Wildlife Refuge 5399 The recent establishment of the Everglades Headwaters National Wildlife Refuge and Conservation Area demonstrates how human dimensions, climate change, and ecological resilience strongly influenced the Paper biological planning process. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service engaged a disparate group of stakeholders, partners, and technical experts to inform the refuge’s conservation design. Human dimensions tools were used to understand the cultural ecosystem services that informed the outdoor recreational compatibility determinations. Partnership engagement was integral in developing the resource management plan. Stakeholder engagement was critical because two-thirds of the refuge will be conservation easements, providing wildlife benefits on lands that will continue to be owned and managed by willing landowners for agricultural production. The final planning document was informed by the biological and social drivers of Central Florida. In the end, the Everglades Headwaters will serve as a wildlife and ecological greenway between existing conservation lands from central Florida to Everglades National Park. Value The Everglades Headwaters NWR is a fusion of theoretical and applied human dimensions in the context of proposition: establishing a federal protected place. Keywords: Human Dimensions, NWR Lead author -

The Capilano Review Do Not Cause Damage to the Walls, Doors, Or Windows

The Capilano Review Do not cause damage to the walls, doors, or windows. — Chelene Knight Editor Fenn Stewart Managing Editor Matea Kulić Editorial Assistant Dylan Godwin Designer Anahita Jamali Rad Contributing Editors Clint Burnham, Roger Farr, Aisha Sasha John, Andrew Klobucar, Natalie Knight, Erín Moure, Lisa Robertson, Christine Stewart, Liz Howard Founding Editor Pierre Coupey Interns Tanis Gibbons and Crystal Henderson The Capilano Review is published by the Capilano Review Contemporary Arts Society. Canadian subscription rates for one year are $25, $20 for students, $60 for institutions. Rates plus S&H. Address correspondence to The Capilano Review, 102-281 Industrial Avenue, Vancouver, BC V6A 2P2. Subscribe online at www.thecapilanoreview.com/subscribe. For submission guidelines, visit www.thecapilanoreview.com/submit. The Capilano Review does not accept hard-copy submissions or submissions sent by email. Copyright remains the property of the author or artist. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the author or artist. The Capilano Review gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Canada Council for the Arts. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Periodical Fund of the Department of Canadian Heritage. The Capilano Review is a member of Magazines Canada, the Magazine Association of BC, and the BC Alliance for Arts and Culture (Vancouver). Publications mail agreement -

St. Paul's Indian Residential School and the Connection to Squamish Nation

BACKGROUNDER Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh Nations Announce Investigation at Former St. Paul’s Indian Residential School Site On August 10, 2021, the Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation) announced it had embarked on an Indigenous-led initiative, on behalf of its people and in partnership with its relatives the xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm (Musqueam) and səl̓ilw̓ ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, to find answers about the children who attended the former St. Paul’s Indian Residential School but never made it home. Catholic church officials with Indigenous children outside St. Paul's Indian Residential School in North Vancouver. Source: INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL HISTORY AND DIALOGUE CENTRE THE HISTORY OF ST. PAUL’S INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL Also known as the Squamish Indian Residential School, St. Paul’s Indian Residential School in present-day North Vancouver was the only residential school in Metro Vancouver. It was located next to the Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh Úxwumixw community of Eslhá7an. In 1899, the federal government’s Department of Indian Affairs established it as a residential school and was responsible for its funding. The school was managed and operated by the Roman Catholic Religious Teaching Order, the Sisters of Child Jesus. Children in the school were segregated by age group and gender, and were often not permitted to visit other family members in the school. They were stripped of their culture and punished for speaking their native languages or taking part in their cultural traditions. Approximately 75 Indigenous children lived at the three-storey wood-frame residential school at any given time, and there was documentation of overcrowding. In 1931, the local Indian Agent reported after an inspection that he suspected the children were not being fed properly.