Celia Laighton Thaxter (1835-1894)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celia Thaxter and the Isles of Shoals Deborah B

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 12-2003 Constructing identity in place : Celia Thaxter and the Isles of Shoals Deborah B. Derrick University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Derrick, Deborah B., "Constructing identity in place : Celia Thaxter and the Isles of Shoals" (2003). Student Work. 58. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/58 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY IN PLACE: CELIA THAXTER AND THE ISLES OF SHOALS A Thesis Presented to the Department of Communication and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by Deborah B. Derrick December 2003 UMI Number: EP72697 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disssrtafioft Publishing UMI EP72697 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest ProQuest LLC. -

Willa Cather and American Arts Communities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2004 At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jewell, Andrew W., "At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES by Andrew W. Jewel1 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Susan J. Rosowski Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2004 DISSERTATION TITLE 1ather and Ameri.can Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewel 1 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Approved Date Susan J. Rosowski Typed Name f7 Signature Kenneth M. Price Typed Name Signature Susan Be1 asco Typed Name Typed Nnme -- Signature Typed Nnme Signature Typed Name GRADUATE COLLEGE AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES Andrew Wade Jewell, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2004 Adviser: Susan J. -

Celia Thaxter Collection, 1874-1996

Celia Thaxter collection, 1874-1996 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2019. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Maine Women Writers Collection Abplanalp Library University of New England 716 Stevens Avenue Portland, Maine 04103 [email protected] URL: http://www.une.edu/mwwc Celia Thaxter collection, 1874-1996 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical/Historical Note ......................................................................................................................... 3 Collection Scope and Content ....................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

Finding Aid to the Collection of Celia Thaxter Materials

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Finding Aids Special Collections & Archives 2018 Finding Aid to the Collection of Celia Thaxter Materials Celia Thaxter Colby College Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/findingaids Part of the Horticulture Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Painting Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Collection of Celia Thaxter Materials, Colby College Special Collections, Waterville, Maine. This Finding Aids is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections & Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Finding Aid to the Collection of Celia Thaxter Materials THAXTER.1 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on October 30, 2018. Finding aid is written in: English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Colby College Special Collections Finding Aid to the Collection of Celia Thaxter Materials THAXTER.1 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents note ............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note -

Archaeology, Antiquarianism, and the Landscape in American Women's Writing, 1820--1890 Christina Healey University of New Hampshire, Durham

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2009 Excavating the landscapes of American literature: Archaeology, antiquarianism, and the landscape in American women's writing, 1820--1890 Christina Healey University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Healey, Christina, "Excavating the landscapes of American literature: Archaeology, antiquarianism, and the landscape in American women's writing, 1820--1890" (2009). Doctoral Dissertations. 475. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/475 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXCAVATING THE LANDSCAPES OF AMERICAN LITERATURE- ARCHAEOLOGY, ANTIQUARIAN ISM, AND THE LANDSCAPE IN AMERICAN WOMEN'S WRITING, 1820-1890 BY CHRISTINA HEALEY B.A., Providence College, 1999 M.A., Boston College, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy , in English May, 2009 UMI Number: 3363719 Copyright 2009 by Healey, Christina INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Celia Thaxter: Seeker of the Unattainable

Colby Quarterly Volume 6 Issue 12 December Article 3 December 1964 Celia Thaxter: Seeker of the Unattainable Perry D. Westbrook Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 6, no.12, December 1964, p.497-512 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Westbrook: Celia Thaxter: Seeker of the Unattainable A Cf]aUand for 1835-1894 On the 70th Anniversary * Fitting the tinze, in plenitude of power, A t close of summer, that her life should cease. Not as a stranded wreck, Sea-swept froln deck to deck. But fading swiftly into that great Peace, A t night and silently, like sOlne sweet flower. A. w. E. Published by Digital Commons @ Colby, 1964 1 Colby Quarterly, Vol. 6, Iss. 12 [1964], Art. 3 MRS. THAXTER IN 1880 https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq/vol6/iss12/3 2 Westbrook: Celia Thaxter: Seeker of the Unattainable Colby Library Quarterly Series VI December 1964 No. 12 CELIA THAXTER: SEEKER OF THE UNATTAINABLE By PERRY D. WESTBROOK CELIA THAXTER once said: "I longed to speak [those] things which made, life so sweet, - to speak the wind, the cloud, the bird's flight, the sea's murmur, - and the wish grew." Had her wish been granted, she would have been merely another of the writers of the "genteel tradition" that flourish·ed in the latter part of the nineteenth century - a composer of ditties about flowers and babies, of essays concocted from one part Emerson diluted with two parts of Henry Ward Beecher. -

James Thomas Fields Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2z09n5tc No online items James Thomas Fields Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Huntington Library staff and updated by Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2000 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. James Thomas Fields Papers: mssFI 1 Finding Aid Descriptive Summary Title: James Thomas Fields Papers Dates: 1767-1914 Bulk dates: 1850-1914 Collection Number: mssFI Creator: Fields, James Thomas Extent: 5,438 items in 74 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collections consist primarily of letters, as well as poems and manuscripts, from various American and British authors to American editor, publisher, and poet James Thomas Fields (1817-1881), mostly relating to publication of their manuscripts by his firm Ticknor and Fields and in The Atlantic Monthly. The collection also includes letters to Fields's wife Annie Fields (1834-1915) concerning literary matters. Language of Material: The records are in English. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, please visit the Huntington's website: www.huntington.org. Processing Information The collection was processed and a summary report first created in 1976, and revised in 1983. -

The Role of Celia Thaxter in American Literary History: an Overview

Colby Quarterly Volume 17 Issue 4 December Article 6 December 1981 The Role of Celia Thaxter in American Literary History: An Overview Jane Vallier Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 17, no.4, December 1981, p.238-255 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Vallier: The Role of Celia Thaxter in American Literary History: An Overvi The Role of Celia Thaxter in American Literary History: An Overview by JANE VALLIER HERE are two stories to tell about the lives of many women writers T in nineteenth-century America. The first story, whether it be told about Margaret Fuller, Emily Dickinson or Celia Thaxter, is a rather conventional melodrama about a talented woman who stole time from her domestic duties to write an amazing quantity of literature, some of it a recognizable variation on the "standard" literature written by Emer son, Longfellow and Whittier. The superficial "first story" has been chronicled in American literary history by generations of critics and his torians who concluded that women in nineteenth-century America with the exception of Emily Dickinson, perhaps-wrote an enormous pile of second-rate literature, the imputed inferiority of which was based in the erroneous but widespread belief that female experience was in itself an inferior fornl of human experience. Typical of the muddled judgment women's writing has received is this statement made by Robert Spiller in The Cycle ofAmerican Literature, 1955: "There is something about the way women lived in the nineteenth century that encouraged repression."· Spiller, like most of the literary historians of his and earlier generations, was content to leave that "something" a vague and unsolvable mystery; "something" was not worth investigating. -

ISHRA NEWSLETIER Islesof Shoals Historical and Researchassociation Volume 7 Number 1 February 1998

, f ISHRA NEWSLETIER Islesof Shoals Historical and ResearchAssociation Volume 7 Number 1 February 1998 FAll MEETING (from Secretary Don Bassett's minutes) he meeting was held at Tthe Seacoast Science Center at 7pm on Tuesday, November 11, 1997. President Bob Hochstetler opened the meeti ng. The minutes of the last meet- ing, a copy of which were ava i Iable for perusa I before the meeti ng, were accepted without correc- tion. Bob asked members willing to serve as officers or directors to contact Wendy Lull (Seacoast Science Center: 603-436- Committee Reports 8043), chairperson of the Nominations Committee. Several positions will be open, including all the offi- Collections cers. Bob recommended that the treasurer, to be Maryellen Burke reported that many manuscripts elected, have access to a computer and a Quicken from the Vaughn Collection on Star Island have program. He also distributed a printout of courses been sent to the Portsmouth Athenaeum to provide a that will be available at the Shoals Marine Lab next safe environment and constant temperature for summer and announced that Ernestine Firth would preservation as well as making the material more have copies of her booklet of poems, Star Songs, for accessible for research. Maryellen asked for help in sale after the meeting. finding a primary source record of Celia Thaxter's Treasurer Bob Tuttle reported that ISHRA started birthplace on Daniel Street in Portsmouth. She the year on January 1, 1997, with a balance of $3, wants to verify this before suggesting that ISHRA 362.00. Transactions during the year resulted in an consider putting a plaque at the site. -

NOMINATION FORM York for NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Continuation Sheet) •AY 1 Fi 1974 (Number All Entries)

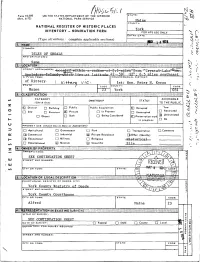

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE „ . Xl COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORI C PLACES York INVENTORY - NOMINATION F UKM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicabh 3sec"°"iv MAY 16W4 COMMON: ISLES OF SHOALS AND/OR HISTORIC: Same !iS|:;S:£*:!;|i-::j;^ STREET AND NUMBER: -tiO-CErCeuT_-. ^-rip J..T.J, WTtTttli,.,4_i.t.,J . — fct, — L<£Q. , , 1 iiis-of— 2r5"-mrl-erg~f rom -" Crys tai—Lake-^-on^ M 'Ap pied&re—T'si'antiT—^tiip.?! ~ -1 iV « • -a t 1 at itiid«>v..42-59J" '-12",* 6.5 miles southeast CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: of Kittery. (_ &++&+* i/ic. 1st: Hon. Peter N. Kvros STATE / CODE COUNTY: CODE Maine ^J York: 031 |$i|(Vf?:£&i? ¥ii'i't*'jF'&'i/\ti y '• ]- : '''"' ^ ''-'• ''' '•''••••••'•'••''•''• : - V &¥&••''• V:'Xf ••'••&•'•': •?•:• ':':: : : : •:•:••>: 'f •:•••.'•:'••: ••:• ':•; lllillllil;llllllllllllllilllili::il!lllliPlll^lt:'||i|l!ll||l 1/1 CATEGORY OWNER SHIP < STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC E District Q Building CD Public Public Acquisition: |T] Occupied Yes: n Site Q Structure S Private C 1 In Process r-, Unoccupied D R^tricted D Object D Both C3 Being Considered ^ p reservatjon work 3 Unrestricted in progress ' — ' u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) FT! Agricultural | | Government Q Park I 1 Transportation D Comments OH (3 Commercial CD Industrial gj] Priva te Residence (jjj: Other (Specify) S Educational l~1 Mi itary Q Relig ious His t or i p alr 1 | Entertainment Ixl Museum (^) Scien tific Sit*3 } OWNER'S -

Finding Aid to the Collection of Celia Thaxter Materials THAX.1 Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared By

Finding Aid to the Collection of Celia Thaxter Materials THAX.1 Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Colby College Special Collections, Waterville, Maine This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit August 22, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Colby College Special Collections 2011 5150 Mayflower HIll Waterville, ME, 04941 (207) 859-5150 [email protected] Finding Aid to the Collection of Celia Thaxter Materials THAX.1 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................4 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Series -

Celia Thaxter: a Memorable Murder

The Library of America • Story of the Week Reprinted from True Crime: An American Anthology (The Library of America, 2008), pages 131–155. ©2008 Literary Classics of the U.S., Inc. Originally published in the May 1875 issue of Atlantic Monthly. CELIA THAXTER Until Lizzie Borden’s father and step m other received their famous whacks on the sweltering afternoon of August 4, 1892, the most notori- ous axe-murder case in the annals of New En gland crime was the atroc- ity committed in 1873 on Smutty Nose, one of the small, barren Isles of Shoals, a rugged archipelago of small islands ten miles off the coast of New Hampshire. Sensational as it was at the time, however, the crime would have fallen into obscurity had it not been for the New En gland writer Celia Laighton Thaxter (1835– 1894). Thaxter grew up on the Isles of Shoals, where her family eventually opened a summer hotel that became a popular resort for New En gland writers and artists, among them Nathaniel Hawthorne, Childe Hassam, James Russell Lowell, and Richard Henry Dana. Married at 16 to her father’s business partner, Levi Thaxter, Celia accompanied him to Newtonville, Mas sa- chusetts, where she found herself trapped in what she described as a “household jail.” Longing for the stark beauties of her childhood home, she wrote a poem called “Land-locked” that was published by Lowell in the March 1861 Atlantic Monthly, launching a literary career that would include such books as Among the Isles of Shoals (1873) and An Island Garden (1894).