Political Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Wild Capitalism'

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Anthropology Department Faculty Publication Anthropology Series January 2005 'Wild Capitalism’ and ‘Ecocolonialism’: A Tale of Two Rivers Krista Harper University of Massachusetts - Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/anthro_faculty_pubs Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Eastern European Studies Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Public Affairs Commons, Public Policy Commons, Science and Technology Policy Commons, Science and Technology Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Krista, "'Wild Capitalism’ and ‘Ecocolonialism’: A Tale of Two Rivers" (2005). American Anthropologist. 72. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/anthro_faculty_pubs/72 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KRISTA HARPER “Wild Capitalism” and “Ecocolonialism”: A Tale of Two Rivers ABSTRACT The development and pollution of two rivers, the Danube and Tisza, have been the site and subject of environmental protests and projects in Hungary since the late 1980s. Protests against the damming of the Danube rallied opposition to the state socialist government, drawing on discourses of national sovereignty and international environmentalism. The Tisza suffered a major environmental disaster in 2000, when a globally financed gold mine in Romania spilled thousands of tons of cyanide and other heavy metals into the river, sending a plume of pollution downriver into neighboring countries. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

(1 of 432) Case:Case 18-15845,1:19-cv-01071-LY 01/27/2020, Document ID: 11574519, 41-1 FiledDktEntry: 01/29/20 123-1, Page Page 1 1 of of 432 239 FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT THE DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL No. 18-15845 COMMITTEE; DSCC, AKA Democratic Senatorial Campaign D.C. No. Committee; THE ARIZONA 2:16-cv-01065- DEMOCRATIC PARTY, DLR Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. OPINION KATIE HOBBS, in her official capacity as Secretary of State of Arizona; MARK BRNOVICH, Attorney General, in his official capacity as Arizona Attorney General, Defendants-Appellees, THE ARIZONA REPUBLICAN PARTY; BILL GATES, Councilman; SUZANNE KLAPP, Councilwoman; DEBBIE LESKO, Sen.; TONY RIVERO, Rep., Intervenor-Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Arizona Douglas L. Rayes, District Judge, Presiding (2 of 432) Case:Case 18-15845,1:19-cv-01071-LY 01/27/2020, Document ID: 11574519, 41-1 FiledDktEntry: 01/29/20 123-1, Page Page 2 2 of of 432 239 2 DNC V. HOBBS Argued and Submitted En Banc March 27, 2019 San Francisco, California Filed January 27, 2020 Before: Sidney R. Thomas, Chief Judge, and Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain, William A. Fletcher, Marsha S. Berzon*, Johnnie B. Rawlinson, Richard R. Clifton, Jay S. Bybee, Consuelo M. Callahan, Mary H. Murguia, Paul J. Watford, and John B. Owens, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge W. Fletcher; Concurrence by Judge Watford; Dissent by Judge O’Scannlain; Dissent by Judge Bybee * Judge Berzon was drawn to replace Judge Graber. Judge Berzon has read the briefs, reviewed the record, and watched the recording of oral argument held on March 27, 2019. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: for the END IS a LIMIT

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FOR THE END IS A LIMIT: THE QUESTION CONCERNING THE ENVIRONMENT Ozguc Orhan, Doctor of Philosophy, 2007 Dissertation Directed By: Professor Charles E. Butterworth Department of Government and Politics Professor Ken Conca Department of Government and Politics This dissertation argues that Aristotle’s philosophy of praxis (i.e., ethics and politics) can contribute to our understanding of the contemporary question concerning the environment. Thinking seriously about the environment today calls for resisting the temptation to jump to conclusions about Aristotle’s irrelevance to the environment on historicist grounds of incommensurability or the fact that Aristotle did not write specifically on environmental issues as we know them. It is true that environmental problems are basically twentieth-century phenomena, but the larger normative discourses in which the terms “environmental” and “ecological” and their cognates are situated should be approached philosophically, namely, as cross-cultural and trans-historical phenomena that touch human experience at a deeper level. The philosophical perspective exploring the discursive meaning behind contemporary environmental praxis can reveal to us that certain aspects of Aristotle’s thought are relevant, or can be adapted, to the ends of environmentalists concerned with developmental problems. I argue that Aristotle’s views are already accepted and adopted in political theory and the praxis of the environment in many respects. In the first half of the dissertation, I -

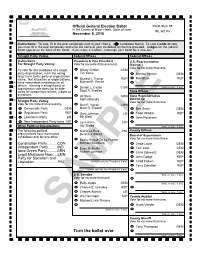

Turn the Ballot Over General Election Des Moines County, Iowa Tuesday

OFFICIAL BALLOT General Election Precinct Official's Initials Des Moines County, Iowa Des Moines County Auditor & Tuesday, November 8, 2016 Commissioner of Elections Pct 9 00900 INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTERS Using blue or black ink, completely fill in the target next to the candidate or response of your choice like this: Write-in To vote for a write-in candidate, write the person's name on the line provided and darken the target. Do not cross out. If you change your mind, exchange your ballot for a new one. The Judicial Ballot is located on the back of the ballot. Federal Offices State Offices For President and Vice President Partisan Offices For State Senator Vote for no more than ONE Team District 44 DEM Hillary Clinton Vote for no more than One Straight Party Political Organizations Tim Kaine Thomas Courtney DEM Democratic Party (DEM) Donald J. Trump REP Thomas A. Greene REP Republican Party (REP) Michael R. Pence Libertarian Party (LIB) New Independent Party Iowa (NIP) Darrell L. Castle CON Scott N. Bradley (Write-in vote, if any) Other Political Organizations For State Representative The following organizations have nominated Jill Stein GRN District 087 candidates for only one office: Ajamu Baraka Constitution Party (CON) Vote for no more than One Iowa Green Party (GRN) Dan R. Vacek LMN Dennis M. Cohoon DEM Legal Marijuana Now (LMN) Mark G. Elworth Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) Gary Johnson LIB Bill Weld (Write-in vote, if any) Straight Party Voting County Offices To vote for all candidates from a single Lynn Kahn NIP party, fill in the target in front of the party Jay Stolba name. -

ID COMMITTEE 6056 Bankers Unite in Legislative Decisions AKA: BUILD 6237 ABATEPAC (A Brotherhood Aimed Towards Education) 9738 Actblue Iowa

ID COMMITTEE 6056 Bankers Unite in Legislative Decisions AKA: BUILD 6237 ABATEPAC (A Brotherhood Aimed Towards Education) 9738 ActBlue Iowa 9733 Advocates for Addiction Prevention & Treatment PAC (AAPT PAC) 9693 African American Leadership Committee 6113 AFSCME/Iowa Council 61 P.E.O.P.L.E. 9742 All Children Matter-Iowa 6433 Alliant Energy Iowa/Minnesota Governmental Action Committee 6248 American Federation of State County Municipal Employees 1868 Polk Co. 9768 Ameristar PAC 9703 Ankeny Area Democrats 6008 Associated Builders and Contractors of Iowa PAC 6004 Associated General Contractors of Iowa PAC 6159 Aviva USA PAC (formerly AmerUs Group PAC) 9811 CA 4 Iowa 6271 Carpenters Local 106 Legislative Improvement Comm. 9512 Carroll County Council of Republican Women 6475 Casey's PAC 9694 Cedar Rapids Physician-Hospital Organization Political Action Committee (PHO-PAC) 9680 Cedar Rapids Trades Council CR/IC Building Trades PAC 6017 Central Iowa Building and Construction Trades Council PAC 9663 Citizens for Preservation of Racing 6375 Civil Servants Political Education League 9810 Clarke County Republican Women 9521 Clinton County Republican Women's Club 6244 Clinton Labor Congress Comm. On Political Education 9763 College and Young Democrats of Iowa PAC 6347 Committee for Pension Reform (CPR) 9798 Common Sense 6019 Communications Workers of America Local 7102 POL 9710 Communications Workers of America Local 7110 COPE Fund 6160 Community Bankers of Iowa Political Action Committee 9522 Crawford County Republican Women 6021 Credit Union PAC 6439 CWA Council of the State of IA COPE Fund 6369 DAWN'S LIST 6027 Deere & Company PAC - Iowa 9764 Delta Dental of Iowa PAC 9597 Democratic Women of Buchanan County 9709 Des Moines County Job Opportunity and Business PAC 6028 District Union #431 UFCW Political Action Account 9757 Dow AgroSciences Iowa PAC 6366 Dubuque Federation of Labor COPE Committee 9805 Educational Opportunities PAC 6406 EMILY's List -- Iowa 6033 Employers Mutual Casualty Co. -

GENERAL ELECTION November 6, 2012 Candidate List

GENERAL ELECTION November 6, 2012 Candidate List PRESIDENT/VICE PRESIDENT DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTION PARTY REPUBLICAN Barack Obama/Joe Biden* Virgil Goode/James Clymer Mitt Romney/Paul Ryan 5046 South Greenwood Avenue 90 East Church Street 3 South Cottage Road Chicago, IL 60615 Rocky Mount, VA 24151 Belmont, MA 02478 312-985-1700 540-483-9030 857-288-3500 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] PARTY FOR SOCIALISM AND IOWA GREEN PARTY LIBERTARIAN PARTY LIBERATION Jill Stein/Cheri Honkala Gary Johnson/James P. Gray Gloria LaRiva/Stefanie Beacham 17 Trotting Horse Drive 850 C. Camino Chamisa 3207 Mission Street, #9 Lexington, MA 02421 Santa Fe, NM 87501 San Francisco, CA 94110 781-674-1377 505-270-0307 202-234-2828 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SOCIALIST WORKERS PARTY NOMINATED BY PETITION (NBP) James Harris/Alyson Kennedy Jerry Litzel/Jim Litzel 3024 S. Kenwood Avenue, #3 3408 Tripp Street Los Angeles, CA 90007 Ames, IA 50014 323-804-4955 515-292-8123 [email protected] [email protected] '*incumbent NOTE: Due to redistricting, all Congressional and legislative district numbers and boundaries have changed. Candidates are listed as incumbents if they are currently serving in the same office to which they seek election. GENERAL ELECTION November 6, 2012 Candidate List UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE DISTRICT 4 DEMOCRATIC NOMINATED BY PETITION (NBP) REPUBLICAN Christie Vilsack Martin James Monroe Steve King* 2202 Pinehurst Dr 602 Walnut St #3 3897 Esther Ave Ames, IA 50010-4560 Battle Creek, IA 51006 Kiron, IA 51448 515-233-5858 817-897-5593 712-273-5097 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] '*incumbent NOTE: Due to redistricting, all Congressional and legislative district numbers and boundaries have changed. -

Environmentalism and the Public Sphere in Postsocialist Hungary Krista Harper University of Massachusetts - Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Anthropology Department Faculty Publication Anthropology Series January 1999 Citizens or Consumers?: Environmentalism and the Public Sphere in Postsocialist Hungary Krista Harper University of Massachusetts - Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/anthro_faculty_pubs Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Krista, "Citizens or Consumers?: Environmentalism and the Public Sphere in Postsocialist Hungary" (1999). Radical History Review. 74. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/anthro_faculty_pubs/74 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Citizens or Consumers?: Environmentalism and the Public Sphere in Postsocialist Hungary Krista Harper INTRODUCTION Much of the most vital activism of the post-1989 environmental move- ment in Hungary addresses the development of consumer culture and the expansion of transnational corporations in East-Central Europe. In actions against McDonald's conquest of the urban landscape and the ubiquitous presence of advertisements for transnational corporations, activists contrast cherished notions of decentralization and local control with the emergence of an imperialistic, global consumer culture. These issues came to the forefront of environmental debates while I was living in Hungary from 1995 to 1997, conducting ethnographic research on environmental groups. This paper will present several cases of Hungar- ian activism against well-known transnationals, examining how issues of the public sphere-public space, public access to information and debate, and public participation-are redefined as "environmental" struggles. -

Official General Election Ballot

11 OFFICIAL GENERAL ELECTION BALLOT FEDERAL FEDERAL Pottawattamie County State of Iowa For United States Representative Official Ballot For President/Vice President District 3 General Election Vote for no more than ONE Vote for no more than ONE November 8, 2016 21 David Young Republican Party Donald J. Trump Republican Party Jim Mowrer Michael R. Pence Democratic Party Bryan Jack Holder Marilyn Jo Drake Libertarian Party Hillary Clinton Democratic Party County Auditor and Tim Kaine Claudia Addy Commissioner of Elections Joe Grandanette Gary Johnson Libertarian Party Bill Weld INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTER (Write-in vote, if any) 1. Voting Mark. To vote, fill in the Lynn Kahn oval next to your choice. New Independent STATE Candidate Name Jay Stolba Party Iowa Candidate Name 2. Write-in Votes. To vote for a For State Senator District 8 person whose name is not on the Darrell L. Castle 40 Constitution Party Vote for no more than ONE ballot, write the name on the write-in Scott N. Bradley line below the list of candidates and 41 fill in the oval next to it. Dan Dawson 3. Use only a black pen to mark Republican Party Jill Stein 42 your ballot, unless a marking Iowa Green Party Michael E. Gronstal device is provided by an election Ajamu Baraka Democratic Party official. 43 4. Do not cross out. If you change your mind, exchange your ballot for (Write-in vote, if any) Gloria La Riva Party for Socialism a new one. Dennis J. Banks 5. Where to find the Judges: On and Liberation the back of this ballot, in the middle For State Representative or right column. -

General Election Candidate List

Federal and State Certified Candidate List November 8, 2016 General Election For the Office Of… Party Ballot Name(s) Address Phone Email Filing Date President/Vice President Republican Donald J. Trump/Michael R. Pence 721 Fifth Avenue PH, New York, NY 10022/4750 N Meridian St, Indianapolis, IN, 46208 646-736-1779 [email protected] 7/27/2016 President/Vice President Democratic Hillary Clinton/Tim Kaine PO Box 5256 New York, NY 10185 646-854-1160 [email protected] 8/11/2016 President/Vice President Constitution Party Darrell L. Castle/Scott N. Bradley 2586 Hocksett Cove, Germantown, TN 38139/1496 E 2700 North, North Logan, Utah 84341 901-481-5441/435-753-8844 [email protected]/[email protected] 8/15/2016 President/Vice President Iowa Green Party Jill Stein/Ajamu Baraka 22 Kendall Rd, Lexington, MA 02421 781-382-5658 [email protected]/[email protected] 8/1/2016 & 8/19/2016 President/Vice President Legal Marijuana Now Dan R. Vacek/Mark G. Elworth 2864 Whitmore St NE, Omaha, NE 68112 402-812-1600 [email protected]/[email protected] 8/19/2016 President/Vice President Libertarian Gary Johnson/Bill Weld 10 W Broadway Ste 202, Salt Lake City, UT 84101 801-303-7922 [email protected] 8/19/2016 President/Vice President New Independent Party Iowa Lynn Kahn/Jay Stolba PO Box 497, Kensington, MD, 20895/350 Parkland Dr SE, Cedar Rapids, IA 52403 603-717-1012/319-533-5690 [email protected]/[email protected] 8/19/2016 President/Vice President Party for Socialism and Liberation Gloria La Riva/Dennis J. -

The Austrian Imaginary of Wilderness: Landscape, History and Identity In

The Austrian Imaginary of Wilderness: Landscape, History and Identity in Contemporary Austrian Literature Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Magro Algarotti, M.A. Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures. The Ohio State University 2012 Committee: Gregor Hens, Advisor Bernd Fischer Bernhard Malkmus Copyright by Jennifer Magro Algarotti 2012 Abstract Contemporary Austrian authors, such as Christoph Ransmayr, Elfriede Jelinek, Raoul Schrott, and Robert Menasse, have incorporated wilderness as a physical place, as a space for transformative experiences, and as a figurative device into their work to provide insight into the process of nation building in Austria. At the same time, it provides a vehicle to explore the inability of the Austrian nation to come to terms with the past and face the challenges of a postmodern life. Many Austrian writers have reinvented, revised, and reaffirmed current conceptions of wilderness in order to critique varying aspects of social, cultural, and political life in Austria. I explore the way in which literary texts shape and are shaped by cultural understandings of wilderness. My dissertation will not only shed light on the importance of these texts in endorsing, perpetuating, and shaping cultural understandings of wilderness, but it also will analyze their role in critiquing and dismantling the predominant commonplace notions of it. While some of the works deal directly with the physical wilderness within Austrian borders, others employ it as an imagined entity that affects all aspects of Austrian life. ii Dedication To my family, without whose support this would not have been possible. -

Turn the Ballot Over Write-In Vote, If Any

11 Official General Election Ballot Ballot Style 66 in the County of Black Hawk, State of Iowa WL W3 P5 November 8, 2016 21 Instructions: To vote, fill in the oval completely next to your choice. ( Candidate Name) To cast a write-in vote, you must fill in the oval completely and write the name of your candidate on the line provided. Judges for the judicial ballot appear on the back of the ballot. If you make a mistake, exchange your ballot for a new one. Straight Party Voting Federal Offices Federal Offices Instructions President & Vice President U.S. Representative For Straight Party Voting: Vote for no more than one team. District 1 Vote for no more than one. To vote for all candidates of a single Hillary Clinton DEM party organization, mark the voting Tim Kaine Monica Vernon DEM target next to the party or organization name. Not all parties or organizations Donald J. Trump REP Rod Blum REP 40 have nominated candidates for all Michael R. Pence 41 offices. Marking a straight party or organization vote does not include Darrell L. Castle CON Write-in vote, if any. votes for nonpartisan offices, judges or Scott N. Bradley State Offices questions. Jill Stein GRN State Representative 44 Ajamu Baraka District 62 Straight Party Voting Vote for no more than one. Vote for no more than one party. Dan R. Vacek LMN Democratic Party DEM Mark G. Elworth Ras Smith DEM Republican Party REP Gary Johnson LIB Todd Obadal REP 48 Libertarian Party LIB Bill Weld John Patterson New Independent Party Iowa NIP Lynn Kahn NIP Other Political Organizations Jay Stolba Write-in vote, if any. -

LESS2 A.Indd

LESSA Journal of Degrowth in Scotland Issue 2 | Spring 2021 LESS : A Journal of Degrowth in Scotland 1 CONTENTS TAILOR MADE WELCOME DEGROWTH by Alis le May TO LESS p4 FIRST AS TRAGEDY, then as the natural sense of hope this instills farce. Fish in marine habitats off in the heart. Migratory birds and the coast of our corner of the North fish have left their winter haunts THE Atlantic are “British and happier for and arrived back at UK shores. Our ANTI-D’OH! it”1 after Brexit, according to Jacob annual reminder that freedom of Rees-Moog. Youth unrest ablaze movement is not just a perk that was by Pat Kane in Northern Ireland as lockdown temporarily bestowed upon us as p8 ennui meets marginalisation and a by-product of being a member predictable Brexit realpolitik. state of a single market. interview Mandatory, socially constructed Freedom of movement is with activist, CO-HOUSING royal mourning across the UK as the default mode of all life author and by Sarah Glynn hauntology meets hyperreal soft forms, us included – it’s academic p12 authoritarianism. how evolution itself unfolded. Andrea Vetter Meanwhile, the most symbolic Global freedom of movement on degrowth image from this period remains that is also a core demand of the principles by of a gigantic stuck container ship degrowth movement.2 Svenja Meyerricks. THE CARRYING blocking one of the world’s most In LESS’s first issue in We also have STREAM important trade arteries, laying bare 2021, we look at degrowth a collaborative essay the fragile imbalance of our global in the context of Brexit from the Highlands by Ainslie Roddick, Cáit O’Neill supply chains.