Primates As Pets: Is There a Case for Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

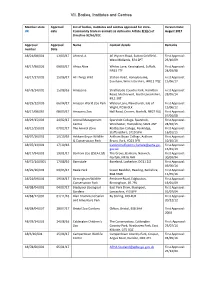

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 Presents the Findings of the Survey of Visits to Visitor Attractions Undertaken in England by Visitbritain

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VisitBritain would like to thank all representatives and operators in the attraction sector who provided information for the national survey on which this report is based. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purp oses without previous written consent of VisitBritain. Extracts may be quoted if the source is acknowledged. Statistics in this report are given in good faith on the basis of information provided by proprietors of attractions. VisitBritain regrets it can not guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in this report nor accept responsibility for error or misrepresentation. Published by VisitBritain (incorporated under the 1969 Development of Tourism Act as the British Tourist Authority) © 2004 Bri tish Tourist Authority (trading as VisitBritain) Cover images © www.britainonview.com From left to right: Alnwick Castle, Legoland Windsor, Kent and East Sussex Railway, Royal Academy of Arts, Penshurst Place VisitBritain is grateful to English Heritage and the MLA for their financial support for the 2003 survey. ISBN 0 7095 8022 3 September 2004 VISITOR ATTR ACTION TRENDS ENGLAND 2003 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS A KEY FINDINGS 4 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Research objectives 12 1.2 Survey method 13 1.3 Population, sample and response rate 13 1.4 Guide to the tables 15 2 ENGLAND VISIT TRENDS 2002 -2003 17 2.1 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by attraction category 17 2.2 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by admission type 18 2.3 England visit trends -

APE RESCUE CENTRE Risk Assessment for School & Group

MONKEY WORLD – APE RESCUE CENTRE Risk Assessment for School & Group Educational Visits 2020/21 Please note: We are a primate rescue and rehabilitation centre and not a zoo, as such the majority of our primates have been abused, neglected and exploited. We would be grateful if you could remind your students of this fact prior to entering our park. We have offered our rescued monkeys and apes sanctuary, free from abuse of any kind and we will not tolerate any behaviour from visitors that causes distress to our primates in anyway e.g. shouting, screaming, banging on the viewing windows, running up and down outside enclosures, throwing items into the enclosures, feeding our primates etc. Visitors that do not abide by the rules of entry to the park will be asked to leave and no refund will be given. Risk Assessment Guidance Monkey World operates under the auspices of the Zoo Licensing Act. We are subject to annual inspections from Enforcement Officers who look at the way we take care of our Primates and the safety of Staff and Visitors. The licence has to be renewed every six years. We strongly recommend that group organisers make a pre-visit to Monkey World and carry out their own risk assessment. We allow one free entry per class/group which is available on request when booking your visit. In the event that a pre-visit is impossible, this document provides a general outline of the risks and controls identified. It is essential that all children are supervised throughout their visit to us and that all attending the visit understand the following: the aims and objectives of the visit how to avoid specific dangers and why they must follow rules why safety precautions are in place and standard of behaviour is expected who is responsible for the Group what to do if approached by anyone outside the Group what to do if separated from the Group the time and place of departure of the Group that in an emergency situation e.g. -

Ape Rescue Chronicle Three Adults Planet Ape Hoodies Adults Planet Ape T-Shirts All Donations Go Into the 100% Ape Rescue Different Goods Times Per Year

Buy a Twister Buy a travel mug Only Beaker £2.99 each and get your first cold drink FREE Charity No. 1126939 + 20%off refills! Only Redeemable at any café or £7.99 each kiosk in the park. and get your first A PE R ESCUE C HRONICLE Recently, the law has changed regarding Issue: 69 SPRING/SUMMER 2018 hot drink FREE data protection regulation (GDPR) which 20%off refills! aims to improve the way companies + handle customer’s personal data. To see how this affects Monkey World adoptive Redeemable at parents, and the way we use and store customer data, please see our data protection compliance statement any café or kiosk online at www.monkeyworld.org/files/monkeyworldgdpr.pdf. If you have any other questions or concerns about data protection, in the park. please contact us at [email protected] ACCOMMODATION NEAR MONKEY WORLD With a portfolio of over 300 personally selected properties, over 100 of which are pet friendly, Dream Cottages are Dorset’s leading holiday cottage agency. Camping or Glamping Call: 01305 789000 Click: www.dream-cottages.co.uk An award winning site, Longthorns is a small farm nestled White Horse Farm Breachfield B&B next to Monkey World. Join us for camping & glamping in a 01963 210222 07776 043140 relaxed atmosphere. We don’t offer regimented pitches, just camp-fires, stargazing and quiet evenings. Enjoy our wonderful woodland walk, alpacas, chickens, horses and cows. Self-catering accommodation 4 cottages, farmhouse annex Friendly B&B located in the heart of Wool, and lodge in rural Dorset. just 2 mins from Monkey World. -

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2005

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VisitBritain would like to thank all representatives and operators in the attraction sector who provided information for the national survey on which this report is based. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purposes without previous written consent of VisitBritain. Extracts may be quoted if the source is acknowledged. Statistics in this report are given in good faith on the basis of information provided by proprietors of attractions. VisitBritain regrets it cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in this report nor accept responsibility for error or misrepresentation. Published by VisitBritain (incorporated under the 1969 Development of Tourism Act as the British Tourist Authority) © 2006 British Tourist Authority (trading as VisitBritain) VisitBritain is grateful to English Heritage and the MLA for their financial support for the 2005 survey. ISBN 0 7095 8276 5 August 2006 VISITOR ATTRACTION TRENDS ENGLAND 2005 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS A KEY FINDINGS 4 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Research objectives 12 1.2 Survey method 14 1.3 Population, sample and response rate 14 1.4 Guide to the tables 16 2 ENGLAND VISIT TRENDS 2004-2005 18 2.1 England visit trends 2004-2005 by attraction category 18 2.2 England visit trends 2004-2005 by admission type 19 2.3 England visit trends 2004-2005 by volume of visits to attractions 21 2.4 England visit trends 2004-2005 by geographic location 21 2.5 England visit trends 2004-2005 by proportion of overseas -

Appendix 1 Licensed Zoos Zoo 1 Licensing Authority Macduff Marine

Appendix 1 Licensed zoos Zoo 1 Licensing Authority Macduff Marine Aquarium Aberdeenshire Council Lake District Coast Aquarium Allerdale Borough Council Lake District Wildlife Park (Formally Trotters) Allerdale Borough Council Scottish Sea Life Sanctuary Argyll & Bute Council Arundel Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust Arun Distict Council Wildlife Heritage Foundation Ashford Borough Council Canterbury Oast Trust, Rare Breeds Centre Ashford Borough Council (South of England Rare Breeds Centre) Waddesdon Manor Aviary Aylesbury Vale District Council Tiggywinkles Visitor Centre Aylesbury Vale District Council Suffolk Owl Sanctuary Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Council Safari Zoo (Formally South Lakes Wild Animal Barrow Borough Council Park) Barleylands Farm Centre Basildon District Council Wetlands Animal Park Bassetlaw District Council Chew Valley Country Farms Bath & North East Somerset District Council Avon Valley Country Park Bath & North East Somerset District Council Birmingham Wildlife Conservation Park Birmingham City Council National Sea Life Centre Birmingham City Council Blackpool Zoo Blackpool Borough Council Sea Life Centre Blackpool Borough Council Festival Park Owl Sanctuary Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Smithills Open Farm Bolton Council Bolton Museum Aquarium Bolton Council Animal World Bolton Council Oceanarium Bournemouth Borough Council Banham Zoo Ltd Breckland District Council Old MacDonalds Educational & Leisure Park Brentwood Borough Council Sea Life Centre Brighton & Hove City Council Blue Reef Aquarium Bristol City -

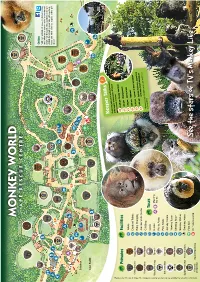

The Monkey World Leaflet &

5 1 6 A 3 2 4 B 1 2 3 4 Chimpanzees Capuchins 5 6 Orang-utans Marmosets Woolly Monkeys Tamarin A B Saki Monkeys Guenons Lemurs Macaques Spider Monkeys Patas Monkey Gibbons Squirrel Monkeys (5 Species) or visit monkeyworld.org visit or centre at the park, call 01929 401012 01929 call park, the at centre adoption adoption the visit information more For rehabilitation of primates. of rehabilitation used solely for the rescue and and rescue the for solely used are adoptions from funds of 100% year. a magazines three and primate certificate & photo of your chosen chosen your of photo & certificate to the park, park, the to pass annual an Includes for yourself! yourself! for dramas at the park. Visit the park to see the stars of the show show the of stars the see to park the Visit park. the at dramas able to immerse themselves in the rescues and day to day day to day and rescues the in themselves immerse to able park’s inhabitants for two decades, and viewers have been been have viewers and decades, two for inhabitants park’s the followed have Life Monkey and Business Monkey TV’s kind in a safe environment. environment. safe a in kind as possible, where they can enjoy the company of their own own their of company the enjoy can they where possible, as Monkey World provides these refugees with as natural a life life a natural as with refugees these provides World Monkey have been neglected or experienced unbelievable cruelty. cruelty. unbelievable experienced or neglected been have 22 different species in our 65 acre park. -

19 ARC Winter 2001

Issue 19:: Winter 2001 Price £1.00 If you remember back to 1999, you may recall front. It was clear that Cookie’s days on the boat that Jim Cronin told the story of a young were numbered. At that time however, there was not chimpanzee named Cookie that had been a lot that could be done as a massive earthquake hit smuggled from the wild to be sold as a pet in Turkey on 17 August 1999. Thousands of people were either dead or injured and it would not have Bodrum, Turkey. The small female chimp been appropriate for the Monkey World team to spent her days tethered to a boat in Bodrum question the Turkish Government about the welfare Harbour and was sometimes taken out late at of a young chimpanzee. night on a “disco cruise” to entertain party goers. Sadly for Cookie, her short life had After two years, Jim and Alison decided that it was time to revisit Turkey and to see if they could find been one of trauma and misery. out what ever happened to Cookie. They called the At a very young age hunters will have killed her Bellerive Foundation in Switzerland, a mother and probably several others in her family conservation organization set up and run by group. The adult chimps will have been butchered Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan. The Prince was also and eaten while the small baby would be shoved concerned about what the illegal pet trade was into a basket and taken to a local African village. doing to the survival of wild chimpanzees and he From there the chimp would have been sold to agreed to help. -

ATIC0786 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 01932 341111 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0786 {By Email} 5 February 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos, which we received on 18 January 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “I've been trying to compile a complete list of the zoological collections of the British Isles. I was wondering whether you would be able to provide me with a list of all premises which currently hold a zoo licence, and all former zoo licence holders too.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on currently licensed zoos in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 18 January 2016 (date of request). See Appendix 2 for a list that APHA hold on closed zoos in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 18 January 2016 (date of request). This data is not complete as zoos typically get deleted from APHA’s database once it becomes inactive. Please note that Local Authorities’ Trading Standards departments are responsible for administering zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981, and APHA are only responsible for maintaining a list of zoo inspectors and nominating them for inspections. Therefore both Appendices have been produced from APHA’s list of inspectors nominated to inspect a zoo. The list in Appendix 1 does not include collections that may be considered a zoo but are exempt from the Act and therefore do not require a licence. -

Ape Rescue Chronicle Three Times Per Year

Letter From the editor It has been a very eventful year celebrating our 25th anniversary. We have had many new arrivals at the park, our building and maintenance team have worked non-stop rebuilding, expanding, and improving many monkey and ape houses and enclosures, we continue to campaign and collect signatures for our Pet Trade Petition, we held numerous events celebrating our 25 years, our rehabilitation and release work in Vietnam continues, and we have received 3 awards this year, the last inducting Jim into the Dorset Hall of Fame. He would have been so happy with all of these achievements. Charity No. 1126939 We now have more than 57,000 signatures - up from 31,000 at the time of the last ARC!! Our target is 100,000 so please help us UK Charity No. 1115350 to get people to sign for the sake of all the monkeys currently kept in the legal British pet trade. The legal trade in primates as pets in Britain continues to be a big problem for us and more tragically for the hundreds of monkeys that are kept in solitary confinement as pets in Britain today. Please help us with our campaign to give ALL monkeys the legal right to specialist care by getting a copy of our Pet Trade Petition and collecting signatures from family, friends, colleagues, or schoolmates. Over the past few months many people have helped with our rescue and rehabilitation work by donating goods such as fruit, vegetables, nuts, dried fruit, seeds, dog biscuits, garlic, peanut butter, honey, jam, vitamins, fleece blankets, sheets, towels, blankets, duvet covers, curtains, hessian sacks, heavy dog toys, tub trugs, baskets, “really useful” boxes, fire hose, rope, ladders, un-used stamps, A PE R ESCUE C HRONICLE medical supplies, biscuits for the team here at the park, and hand made cards to be sold in the shop.