Devolving Climate Change Governance in Kwale County, Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pollution of Groundwater in the Coastal Kwale District, Kenya

Sustainability of Water Resources under Increasing Uncertainty (Proceedings of the Rabat Symposium S1, April 1997). IAHS Publ. no. 240, 1997. 287 Pollution of groundwater in the coastal Kwale District, Kenya MWAKIO P. TOLE School of Environmental Studies, Moi University, PO Box 3900, Eldoret, Kenya Abstract Groundwater is a "last-resort" source of domestic water supply at the Kenyan coast because of the scarcity of surface water sources. NGOs, the Kenya Government, and international aid organizations have promoted the drilling of shallow boreholes from which water can be pumped using hand- operated pumps that are easy to maintain and repair. The shallow nature and the location of the boreholes in the midst of dense population settlements have made these boreholes susceptible to contamination from septic tanks and pit latrines. Thirteen percent of boreholes studied were contaminated with E. coli, compared to 30% of natural springs and 69% of open wells. Areas underlain by coral limestones show contamination from greater distances (up to 150 m away) compared to areas underlain by sandstones (up to 120 m). Overpumping of the groundwater has also resulted in encroachment of sea water into the coastal aquifers. The 200 ppm CI iso-line appears to be moving increasingly landwards. Sea level rise is expected to compound this problem. There is therefore an urgent need to formulate strategies to protect coastal aquifers from human and sea water contamination. INTRODUCTION The Government of Kenya and several nongovernmental organizations have long recog nized the need to make water more easily accessible to the people in order to improve sanitary conditions, as well as to reduce the time people spend searching for water, so that time can be freed for other productive economic and leisure activities. -

Registered Voters Per Constituency for 2017 General Elections

REGISTERED VOTERS PER CONSTITUENCY FOR 2017 GENERAL ELECTIONS COUNTY_ CONST_ NO. OF POLLING COUNTY_NAME CONSTITUENCY_NAME VOTERS CODE CODE STATIONS 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 86,331 136 001 MOMBASA 002 JOMVU 69,307 109 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 126,151 198 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 104,017 165 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 87,326 140 001 MOMBASA 006 MVITA 107,091 186 002 KWALE 007 MSAMBWENI 68,621 129 002 KWALE 008 LUNGALUNGA 56,948 118 002 KWALE 009 MATUGA 70,366 153 002 KWALE 010 KINANGO 85,106 212 003 KILIFI 011 KILIFI NORTH 101,978 182 003 KILIFI 012 KILIFI SOUTH 84,865 147 003 KILIFI 013 KALOLENI 60,470 123 003 KILIFI 014 RABAI 50,332 93 003 KILIFI 015 GANZE 54,760 132 003 KILIFI 016 MALINDI 87,210 154 003 KILIFI 017 MAGARINI 68,453 157 004 TANA RIVER 018 GARSEN 46,819 113 004 TANA RIVER 019 GALOLE 33,356 93 004 TANA RIVER 020 BURA 38,152 101 005 LAMU 021 LAMU EAST 18,234 45 005 LAMU 022 LAMU WEST 51,542 122 006 TAITA TAVETA 023 TAVETA 34,302 79 006 TAITA TAVETA 024 WUNDANYI 29,911 69 006 TAITA TAVETA 025 MWATATE 39,031 96 006 TAITA TAVETA 026 VOI 52,472 110 007 GARISSA 027 GARISSA TOWNSHIP 54,291 97 007 GARISSA 028 BALAMBALA 20,145 53 007 GARISSA 029 LAGDERA 20,547 46 007 GARISSA 030 DADAAB 25,762 56 007 GARISSA 031 FAFI 19,883 61 007 GARISSA 032 IJARA 22,722 68 008 WAJIR 033 WAJIR NORTH 24,550 76 008 WAJIR 034 WAJIR EAST 26,964 65 008 WAJIR 035 TARBAJ 19,699 50 008 WAJIR 036 WAJIR WEST 27,544 75 008 WAJIR 037 ELDAS 18,676 49 008 WAJIR 038 WAJIR SOUTH 45,469 119 009 MANDERA 039 MANDERA WEST 26,816 58 009 MANDERA 040 BANISSA 18,476 53 009 MANDERA -

Marine Science Country Profiles Kenya

INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION & WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN MARINE SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Marine Science Country Profiles Kenya MIKA ODIDO TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE........................................................ 3 1. GENERAL BACKGROUND INFORMATION.......................... 4 1.1 Physical Environment............................................4 1.2 DEMOGRAPHY..............................................10 1.3 ECONOMY ..................................................11 1.4 COASTAL RESOURCES UTILIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT .......17 1.4.1 Tourism/Marine National Parks and Reserves..................... 18 1.4.2 Ports and Harbours......................................... 19 1.4.3 Manufacturing Industries .................................... 19 1.4.4 Mineral Extraction ......................................... 20 1.4.5 Agriculture and Forestry..................................... 20 1.4.6 Fisheries and Aquaculture.................................... 21 2. POLICIES AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK .................... 22 2.1 POLICY AND LEGISLATION ..................................22 2.2 NATIONAL AUTHORITIES IN MARINE AFFAIRS..................23 2.3 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN MARINE AFFAIRS..............26 2.3.1 International Organisation Located in Kenya with interest .........................27 in Marine Activities 3. CAPABILITY AND NEEDS....................................... 27 3.1 ORGANISATIONS INVOLVED IN MARINE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 27 3.1.1 Higher Education Institutions................................. 27 3.1.2 Research Institutions....................................... -

A Study of the Plant Ecology of the Coast Region of Kenya Colony

^•ooooo0Oooooeo0Oooooooeocooo«oeooooooo«oeGso0O«oeoeoeO0oeooGoo0Ooo0OO€ A STUDY OF THE PLANT ECOLOGY OF THE * * * * COAST REGION ¥ ¥ * OF KENYA COLONY M » BRITISH EAST AFRICA * * by JAMES C. MOOMAW * Fulbiißht Research Scholar KENYA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE and EAST AFRICAN AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY RESEARCH ORGANIZATION co-operating with the UNITED STATES EDUCATIONAL COMMISSION in the United Kingdom 7K I960 BRBfFED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER, NAIROBI * Price: Sh. 10 ¥ ISRIC LIBRARY KE - 1960.04 OOOOOOOeOtOtOOGOOOOtOaOtOOOOGtOOOOOtOOOBOOOOOOOK Wageningen The Netherlands Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued ku=. information available for consultation, following Fair Use jdo.oH Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the Wageningen, The Netherlands materials within the archives where the identification of the Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the originators. For questions please contact soil.isricgiwur.nl indicating the item reference number concerned. A STUDY OF THE PLANT ECOLOGY OF THE COAST REGION OF KENYA COLONY BRITISH EAST AFRICA by JAMES C. MOOMAW Fulbright Research Scholar 15 f.o& The following is the first approximation to what will be a more detailed study when more time is avail able. Your comments, corrections, criticisms, and additions are solicited. JAMES C. MOOMAW, Department of Agronomy and Soil Science, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, -

Insecticide Treated Bednets Ownership, Use and Maintenance

INSECTICIDE TREATED BEDNETS OWNERSHIP, USE AND MAINTENANCE BEHAVIOUR IN KWALE, MSAMBWENI AND KINANGO DISTRICTS IN KENYA. MAUREEN KHAMBIRA REG NO: P57/10881/08 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH IN THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY. MARCH 2013 INSECTICIDE TREATED BEDNETS OWNERSHIP, USE AND MAINTENANCE BEHAVIOUR IN KWALE, MSAMBWENI AND KINANGO DISTRICTS IN KENYA. MAUREEN KHAMBIRA REG NO: P57/10881/08 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH IN THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY. MARCH 2013 DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for award of degree in any other university. SIGNATURE: ………………………………….. Date: …………………………….. MAUREEN KHAMBIRA Department of Community Health SUPERVISORS: This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as supervisors. 1. SIGNATURE…………………………………DATE:…………………………… DR. ISAAC MWANZO Department of Community Health Kenyatta University 2. SIGNATURE: …………………………………DATE: …………………… DR. FRANCIS MUTUKU Department of Environmental Health Emory University DEDICATION To my husband Samuel for his compassionate love and patience, my son Duanne Paul for being my enduring delight, my mom Sabina and my sister Darlene for their adamant support, and all those who encouraged me during this study. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with gratitude Emory University for funding my research work. Special thanks goes to Prof. Uriel Kitron for ensuring that the research was uninterrupted. My deepest appreciation goes to my other supervisors, Dr. Isaac Mwanzo and Dr. Francis Mutuku for offering unlimited support, research coordination and facilitation, and for the commitment towards this work. -

Climate Risk Profile Kwale County Highlights

Kenya County Climate Risk Profile Series Climate Risk Profile Kwale County Highlights The agriculture sector plays a crucial role in guaranteeing food and nutrition security, reducing poverty, and creating employment in Kwale County where subsistence farming accounts for about 80% of the average household income. The key agricultural value chain commodities produced by the overwhelming majority of farmers are maize, cowpea, poultry and goat, which contribute to household food and livelihood security. In spite of the importance of agriculture, food insecurity is a critical issue in the. Roughly 70% of the households are considered food poor and 14% report not having enough food to meet their needs, leading to a high incidence of childhood stunting, general undernourishment and general acute malnutrition. Food insecurity peaks between the months of April and June, when the harvested stock is generally depleted. Food insecurity is tied to a combination of factors that include extreme weather and climate conditions, resource management, and access to appropriate inputs. Water is a constraining factor that limits productivity for crop and livestock production. About 30% of the households use machinery and equipment on their farms, but only 2.5% use irrigation water. High prices associated with these inputs have been identified as main barriers to adoption. Reliance on rain fed agriculture makes farmers in Kwale especially vulnerable to climate shocks and changes. Historical records indicate that average temperatures have increased significantly in the past twenty years and the number of heat and drought-stressed days are projected to continue increasing during the First Season (March to May), leading to shorter crop cycles. -

Sub-County Zone Schools LDD TDD PROJECTOR KWALE TSIMBATIWI ZONE Chitsanzepri 19 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE St

SUMMARY OF INSTALLATION OF DEVICES IN PUBLIC PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN KWALE COUNTY Sub-County Zone Schools LDD TDD PROJECTOR KWALE TSIMBATIWI ZONE ChitsanzePri 19 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE St. Josephs 87 2 1 MSAMBWENI MSAMBWENI ZONE Jomo Kenyatta 111 2 1 KINANGO GANDINI ZONE BOFU 100 2 1 KINANGO GANDINI ZONE GANDINI CENTRAL 70 2 1 KINANGO GANDINI ZONE LUTSANGANI 99 2 1 KINANGO GANDINI ZONE YAPHA 63 2 1 KINANGO GANDINI ZONE GONA 62 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE MBULUNI 103 2 1 KINANGO MAZERAS ZONE GWASHENI 143 2 1 KINANGO MAZERAS ZONE MIGUNENI 95 2 1 KINANGO MAZERAS ZONE MAZERAS 98 2 1 KINANGO MAZERAS ZONE MWABILA 72 2 1 KINANGO MAZERAS ZONE MWACHE 76 2 1 KINANGO MAZERAS ZONE MAWEU 74 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE KASAGENI 75 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE KINANGO 68 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE NG'ONZINI 66 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE MAZOLA 90 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE BANG'A 57 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE AMANI 68 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE BISHOP KALU 68 2 1 KINANGO KINANGO ZONE MALUNGONI 42 2 1 KINANGO MAZERAS MAVIRIVIRINI 53 2 1 KINANGO NDAVAYA MWACHANDA 118 2 1 KINANGO NDAVAYA MWALUKOMBE 130 2 1 KINANGO NDAVAYA GULANZE 90 2 1 KINANGO NDAVAYA NDAVAYA 80 2 1 KINANGO NDAVAYA VYOGATO 45 2 1 KINANGO NDAVAYA MBITA 62 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU TARU 119 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU KWAKADOGO 114 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU MWANGEA 128 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU EGU 67 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU MAJI YA CHUMVI 58 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU VINYUNDUNI 74 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU SILALONI 68 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU CHENGONI 128 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU MULUNGUNI 95 2 1 KINANGO SAMBURU JAFFREY 51 2 1 KINANGO MKONGANI MKOMBA 79 2 1 KINANGO MKONGANI MAPONDA 95 2 1 KINANGO MKONGANI NZORA 78 2 1 KINANGO MKONGANI SIMANYA 50 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI MWANGUDA 136 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI GUGU 79 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI VWIVWINI 125 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI MSHIU 75 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI SHIMONI 80 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI KIKONENI 80 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI MABAFWENI 51 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI MARENJE 53 2 1 MSAMBWENI KIKONENI MKWIRO 44 2 1 MSAMBWENI LUNGA LUNGA KIWEGU 110 2 1 MSAMBWENI LUNGA LUNGA JEGO 109 2 1 MSAMBWENI LUNGA LUNGA KIDOMAYA 87 2 1 MSAMBWENI LUNGA LUNGA ST. -

Kwale County Capacity Assessment Report – July 2017

KWALE COUNTY NUTRITION CAPACITY ASSESSMENT PILOT REPORT JULY 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of tables .................................................................................................................................... 3 List of figures ................................................................................................................................... 4 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION OF KWALE COUNTY .............................................................................................. 8 THE KENYA NUTRITION CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK ................................................. 9 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................ 11 CHAPTER 3: RESULTS..................................................................................................................... 16 CHALLENGES, RECCOMENDATIONS AND ACTION PLAN .............................................................. 45 ANNEXES ....................................................................................................................................... 51 2 Kwale -

Figure1: the Map of Kenya Showing 47 Counties (Colored) and 295 Sub-Counties (Numbered)

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health Additional file 1: The county and sub counties of Kenya Figure1: The map of Kenya showing 47 counties (colored) and 295 sub-counties (numbered). The extents of major lakes and the Indian Ocean are shown in light blue. The names of the counties and sub- counties corresponding to the shown numbers below the maps. List of Counties (bold) and their respective sub county (numbered) as presented in Figure 1 1. Baringo county: Baringo Central [1], Baringo North [2], Baringo South [3], Eldama Ravine [4], Mogotio [5], Tiaty [6] 2. Bomet county: Bomet Central [7], Bomet East [8], Chepalungu [9], Konoin [10], Sotik [11] 3. Bungoma county: Bumula [12], Kabuchai [13], Kanduyi [14], Kimilili [15], Mt Elgon [16], Sirisia [17], Tongaren [18], Webuye East [19], Webuye West [20] 4. Busia county: Budalangi [21], Butula [22], Funyula [23], Matayos [24], Nambale [25], Teso North [26], Teso South [27] 5. Elgeyo Marakwet county: Keiyo North [28], Keiyo South [29], Marakwet East [30], Marakwet West [31] 6. Embu county: Manyatta [32], Mbeere North [33], Mbeere South [34], Runyenjes [35] Macharia PM, et al. BMJ Global Health 2020; 5:e003014. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003014 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health 7. Garissa: Balambala [36], Dadaab [37], Dujis [38], Fafi [39], Ijara [40], Lagdera [41] 8. -

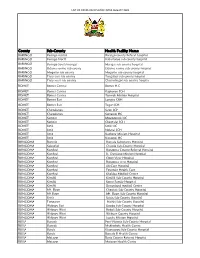

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

Kwale County Strategic Plan 2016/2019

KWALE COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016/2019 ‘Destination Kwale’ Kwale County HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 2016-2019 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................iv Abbreviations and Acronyms ...................................................................................................................v Foreword .................................................................................................................................................vii Preface ...................................................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgement ....................................................................................................................................x Comments from NACC Director ...............................................................................................................xi Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................xii Chapter 1: Background information on Kwale County ........................................................................ 1 Chapter 2: Situation Analysis ................................................................................................................ 3 2.1 HIV Trends in Kwale County ..................................................................................................................... -

Kenya HIV County Profiles

KENYA HIV COUNTY PROFILES ELIMINA TE NEW HIV INFECTION AMONG CHILDREN PREVENT HIV AMONG ACCESSING DRUG USERS TRE ATMENT CLOSING THE REOURCE GAP 2014 Contents Preface ............................................................................1 Makueni County ....................................................76 Background .....................................................................6 Mandera County ...................................................79 National Overview of the Epidemic ...............................8 Marsabit County ....................................................82 HIv and AIdS County Profiles ........................................9 Meru County .........................................................85 Baringo County .....................................................10 Migori County .......................................................88 Bomet County .......................................................13 Mombasa County ..................................................91 Bungoma County ..................................................16 Murang’a County ..................................................94 Busia County .........................................................19 Nairobi County ......................................................97 Elgeyo Marakwet County ......................................22 Nakuru County ....................................................100 Embu County ........................................................25 Nandi County ......................................................103