Development of Bacterial Communities in Biological Soil Crusts Along

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci

Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) 32: 123-166. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21775/cimb.032.123 Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci Miao Lu#, Tao Gong#, Anqi Zhang, Boyu Tang, Jiamin Chen, Zhong Zhang, Yuqing Li*, Xuedong Zhou* State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, PR China. #Miao Lu and Tao Gong contributed equally to this work. *Address correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria belonging to the family Streptococcaceae, which are responsible of multiple diseases. Some of these species can cause invasive infection that may result in life-threatening illness. Moreover, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are considerably increasing, thus imposing a global consideration. One of the main causes of this resistance is the horizontal gene transfer (HGT), associated to gene transfer agents including transposons, integrons, plasmids and bacteriophages. These agents, which are called mobile genetic elements (MGEs), encode proteins able to mediate DNA movements. This review briefly describes MGEs in streptococci, focusing on their structure and properties related to HGT and antibiotic resistance. caister.com/cimb 123 Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) Vol. 32 Mobile Genetic Elements Lu et al Introduction Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria widely distributed across human and animals. Unlike the Staphylococcus species, streptococci are catalase negative and are subclassified into the three subspecies alpha, beta and gamma according to the partial, complete or absent hemolysis induced, respectively. The beta hemolytic streptococci species are further classified by the cell wall carbohydrate composition (Lancefield, 1933) and according to human diseases in Lancefield groups A, B, C and G. -

Validation of the Asaim Framework and Its Workflows on HMP Mock Community Samples

Validation of the ASaiM framework and its workflows on HMP mock community samples The ASaiM framework and its workflows have been tested and validated on two mock metagenomic data of an artificial community (with 22 known microbial strains). The datasets are available on EBI metagenomics database (project accession number: SRP004311). First we checked that the targeted abundances (based on number of PCR product) from both mock datasets were similar to the effective abundance (by mapping reads on reference genomes). Second, taxonomic and functional results produced by the ASaiM framework have been extensively analyzed and compared to expectations and to results obtained with the EBI metagenomics pipeline (S. Hunter et al. 2014). For these datasets, the ASaiM framework produces accurate and precise taxonomic assignations, different functional results (gene families, pathways, GO slim terms) and results combining taxonomic and functional information. Despite almost 1.4 million of raw metagenomic sequences, these analyses were executed in less than 6h on a commodity computer. Hence, the ASaiM framework and its workflows are proven to be relevant for the analysis of microbiota datasets. 1Data On EBI metagenomics database, two mock community samples for Human Microbiome Project (HMP) are available. Both samples contain a genomic mixture of 22 known microbial strains. Relative abundance of each strain has been targeted using the number of PCR product of their respective 16S sequences (Table 1). In first sample (SRR072232), the targeted 16S copies of the strains vary by up to four orders of magnitude between the strains (Table 1), whereas in second sample (SRR072233) the same 16S copy number is targeted for each strain (Table 1). -

Supplementary Information

doi: 10.1038/nature06269 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION METAGENOMIC AND FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF HINDGUT MICROBIOTA OF A WOOD FEEDING HIGHER TERMITE TABLE OF CONTENTS MATERIALS AND METHODS 2 • Glycoside hydrolase catalytic domains and carbohydrate binding modules used in searches that are not represented by Pfam HMMs 5 SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES • Table S1. Non-parametric diversity estimators 8 • Table S2. Estimates of gross community structure based on sequence composition binning, and conserved single copy gene phylogenies 8 • Table S3. Summary of numbers glycosyl hydrolases (GHs) and carbon-binding modules (CBMs) discovered in the P3 luminal microbiota 9 • Table S4. Summary of glycosyl hydrolases, their binning information, and activity screening results 13 • Table S5. Comparison of abundance of glycosyl hydrolases in different single organism genomes and metagenome datasets 17 • Table S6. Comparison of abundance of glycosyl hydrolases in different single organism genomes (continued) 20 • Table S7. Phylogenetic characterization of the termite gut metagenome sequence dataset, based on compositional phylogenetic analysis 23 • Table S8. Counts of genes classified to COGs corresponding to different hydrogenase families 24 • Table S9. Fe-only hydrogenases (COG4624, large subunit, C-terminal domain) identified in the P3 luminal microbiota. 25 • Table S10. Gene clusters overrepresented in termite P3 luminal microbiota versus soil, ocean and human gut metagenome datasets. 29 • Table S11. Operational taxonomic unit (OTU) representatives of 16S rRNA sequences obtained from the P3 luminal fluid of Nasutitermes spp. 30 SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES • Fig. S1. Phylogenetic identification of termite host species 38 • Fig. S2. Accumulation curves of 16S rRNA genes obtained from the P3 luminal microbiota 39 • Fig. S3. Phylogenetic diversity of P3 luminal microbiota within the phylum Spirocheates 40 • Fig. -

Stone-Dwelling Actinobacteria Blastococcus Saxobsidens, Modestobacter Marinus and Geodermatophilus Obscurus Proteogenomes

Stone-dwelling actinobacteria Blastococcus saxobsidens, Modestobacter marinus and Geodermatophilus obscurus proteogenomes Item Type Article Authors Sghaier, Haïtham; Hezbri, Karima; Ghodhbane-Gtari, Faten; Pujic, Petar; Sen, Arnab; Daffonchio, Daniele; Boudabous, Abdellatif; Tisa, Louis S; Klenk, Hans-Peter; Armengaud, Jean; Normand, Philippe; Gtari, Maher Citation Stone-dwelling actinobacteria Blastococcus saxobsidens, Modestobacter marinus and Geodermatophilus obscurus proteogenomes 2015 The ISME Journal Eprint version Post-print DOI 10.1038/ismej.2015.108 Publisher Springer Nature Journal The ISME Journal Rights Archived with thanks to The ISME Journal Download date 28/09/2021 04:14:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10754/577333 1 Stone-dwelling actinobacteria Blastococcus saxobsidens, Modestobacter marinus & 2 Geodermatophilus obscurus proteogenomes 3 Haïtham Sghaier1, Karima Hezbri2, Faten Ghodhbane-Gtari2, Petar Pujic3, Arnab Sen4, Daniele 4 Daffonchio5, Abdellatif Boudabous2, Louis S Tisa6, Hans-Peter Klenk7, Jean Armengaud8, Philippe 5 Normand3*, Maher Gtari2 6 7 1 National Center for Nuclear Sciences and Technology, Sidi Thabet Technopark, 2020 Ariana, Tunisia. 8 2 Laboratoire Microorganismes et Biomolécules ActiVes, UniVersité de Tunis Elmanar (FST) & UniVersité de Carthage 9 (INSAT), Tunis, 2092, Tunisia. 10 3 UniVersité de Lyon, UniVersité Lyon 1, Lyon, France; CNRS, UMR 5557, Ecologie Microbienne, 69622 11 Villeurbanne, Cedex, France. 12 4 NBU Bioinformatics Facility, Department of Botany, UniVersity of North Bengal, Siliguri, 734013, India. 13 5 King Abdullah UniVersity of Science and Technology (KAUST), BESE, Biological and EnVironmental Sciences and 14 Engineering Division, Thuwal, 23955-6900, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia & Department of Food, Environmental and 15 Nutritional Sciences (DeFENS), UniVersity of Milan, Via Celoria 2, 20133 Milan, Italy. 16 6 Department of Molecular, Cellular & Biomedical Sciences, UniVersity of New Hampshire, 46 College Road, Durham, 17 NH 03824-2617, USA. -

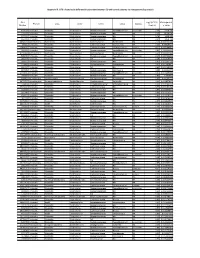

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Relative Genetic Diversity of the Rare and Endangered Agave Shawii Ssp

Received: 17 July 2020 | Revised: 9 December 2020 | Accepted: 14 December 2020 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.7172 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Relative genetic diversity of the rare and endangered Agave shawii ssp. shawii and associated soil microbes within a southern California ecological preserve Jeanne P. Vu1 | Miguel F. Vasquez1 | Zuying Feng1 | Keith Lombardo2 | Sora Haagensen1,3 | Goran Bozinovic1,4 1Boz Life Science Research and Teaching Institute, San Diego, CA, USA Abstract 2Southern California Research Learning Shaw's Agave (Agave shawii ssp. shawii) is an endangered maritime succulent growing Center, National Park Services, San Diego, along the coast of California and northern Baja California. The population inhabiting CA, USA 3University of California San Diego Point Loma Peninsula has a complicated history of transplantation without documen- Extended Studies, La Jolla, CA, USA tation. The low effective population size in California prompted agave transplanting 4 Biological Sciences, University of California from the U.S. Naval Base site (NB) to Cabrillo National Monument (CNM). Since 2008, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA there are no agave sprouts identified on the CNM site, and concerns have been raised Correspondence about the genetic diversity of this population. We sequenced two barcoding loci, rbcL Goran Bozinovic, Boz Life Science Research and Teaching Institute, 3030 Bunker Hill St, and matK, of 27 individual plants from 5 geographically distinct populations, includ- San Diego CA 92109, USA. ing 12 individuals from California (NB and CNM). Phylogenetic analysis revealed the Emails: [email protected]; gbozinovic@ ucsd.edu three US and two Mexican agave populations are closely related and have similar ge- netic variation at the two barcoding regions, suggesting the Point Loma agave popu- Funding information National Park Services (NPS) Pacific West lation is not clonal. -

Streptococcaceae

STREPTOCOCCACEAE Instructor Dr. Maytham Ihsan Ph.D Vet Microbiology 1 STREPTOCOCCACEAE Genus: Streptococcus and Enterocccus Streptococcus and Enterocccus genera, are Gram‐positive ovoid (lanceolate) cocci, approximately 1 μm in diameter, that tend to occur in singles, pairs & chains (rosary‐like) may be long or short. Streptococcus species occur as commensals on skin, upper & lower respiratory tract and mucous membranes; some may act as opportunistic pathogens causing pyogenic infections. Enteroccci spp. are enteric opportunistic & can be found in the intestinal tract of many animlas & humans. Growth & Culture Characteristics • Most streptococci are facultative anaerobes and catalase‐negative. • They are non‐motile and oxidase‐negative and do not form spores & susceptible to desiccation. • They are fastidious bacteria and require the addition of blood or serum to culture media. They grow at temperature ranging from 37°C to 42°C. Group D (Enterocooci), are considered thermophilic & can gorw at 45°C or even higher. • Colonies are small about 1 mm in size, smooth, translucent & may be greyish. • Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus or diplococcus) occurs as slightly pear‐shaped cocci in pairs. Pathogenic strains have thick capsules and produce mucoid colonies or flat colonies with smooth borders & a central concavity “draughtsman colonies” aer 48‐72 hrs on blood agar. These bacteria cause pneumonia in humans and rats. 2 • Some of streptococci grow on MacConkey like: Enterococcus faecalis, Strept. bovis, Sterpt. uberis & strept. lactis producing very tiny colonies like pin‐point appearance aer 48 hrs of incubaon at 37°C. • Streptococci genera grow slowly in broth media, sometimes forming faint opacity; whereas others with a fluffy deposit adherent to the side of the tube. -

Table S4. Phylogenetic Distribution of Bacterial and Archaea Genomes in Groups A, B, C, D, and X

Table S4. Phylogenetic distribution of bacterial and archaea genomes in groups A, B, C, D, and X. Group A a: Total number of genomes in the taxon b: Number of group A genomes in the taxon c: Percentage of group A genomes in the taxon a b c cellular organisms 5007 2974 59.4 |__ Bacteria 4769 2935 61.5 | |__ Proteobacteria 1854 1570 84.7 | | |__ Gammaproteobacteria 711 631 88.7 | | | |__ Enterobacterales 112 97 86.6 | | | | |__ Enterobacteriaceae 41 32 78.0 | | | | | |__ unclassified Enterobacteriaceae 13 7 53.8 | | | | |__ Erwiniaceae 30 28 93.3 | | | | | |__ Erwinia 10 10 100.0 | | | | | |__ Buchnera 8 8 100.0 | | | | | | |__ Buchnera aphidicola 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pantoea 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Yersiniaceae 14 14 100.0 | | | | | |__ Serratia 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Morganellaceae 13 10 76.9 | | | | |__ Pectobacteriaceae 8 8 100.0 | | | |__ Alteromonadales 94 94 100.0 | | | | |__ Alteromonadaceae 34 34 100.0 | | | | | |__ Marinobacter 12 12 100.0 | | | | |__ Shewanellaceae 17 17 100.0 | | | | | |__ Shewanella 17 17 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonadaceae 16 16 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonas 15 15 100.0 | | | | |__ Idiomarinaceae 9 9 100.0 | | | | | |__ Idiomarina 9 9 100.0 | | | | |__ Colwelliaceae 6 6 100.0 | | | |__ Pseudomonadales 81 81 100.0 | | | | |__ Moraxellaceae 41 41 100.0 | | | | | |__ Acinetobacter 25 25 100.0 | | | | | |__ Psychrobacter 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Moraxella 6 6 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudomonadaceae 40 40 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudomonas 38 38 100.0 | | | |__ Oceanospirillales 73 72 98.6 | | | | |__ Oceanospirillaceae -

SCIENCE CHINA Underestimated 14C-Based Chronology of Late Pleistocene High Lake-Level Events Over the Tibetan Plateau and Adjace

SCIENCE CHINA Earth Sciences • RESEARCH PAPER • doi: 10.1007/s11430-014-4993-2 Underestimated 14C-based chronology of late Pleistocene high lake-level events over the Tibetan Plateau and adjacent areas: Evidence from the Qaidam Basin and Tengger Desert LONG Hao1,2* & SHEN Ji1† 1 State Key Laboratory of Lake Sciences and Environment, Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; 2 State Key Laboratory of Loess and Quaternary Geology, Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710075, China Received April 23, 2014; accepted September 25, 2014 The palaeolake evolution across the Tibetan Plateau and adjacent areas has been extensively studied, but the timing of late Pleistocene lake highstands remains controversial. Robust dating of lacustrine deposits is of importance in resolving this issue. This paper presents 14C or optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) age estimates from two sets of late Quaternary lacustrine sequences in the Qaidam Basin and Tengger Desert (northeastern Tibetan Plateau). The updated dating results show: (1) the radiocarbon dating technique apparently underestimated the age of the strata of >30 ka BP in Qaidam Basin; (2) although OSL and 14C dating agreed with each other for Holocene age samples in the Tengger Desert area, there was a significant offset in dating results of sediments older than ~30 ka BP, largely resulting from radiocarbon dating underestimation; (3) both cases imply that most of the published radiocarbon ages (e.g., older than ~30 ka BP) should be treated with caution and perhaps its geological implication should be revaluated; and (4) the high lake events on the Tibetan Plateau and adjacent areas, tradition- ally assigned to MIS 3a based on 14C dating, are likely older than ~80 ka based on OSL chronology. -

Supplemental Material S1.Pdf

Phylogeny of Selenophosphate synthetases (SPS) Supplementary Material S1 ! SelD in prokaryotes! ! ! SelD gene finding in sequenced prokaryotes! We downloaded a total of 8263 prokaryotic genomes from NCBI (see Supplementary Material S7). We scanned them with the program selenoprofiles (Mariotti 2010, http:// big.crg.cat/services/selenoprofiles) using two SPS-family profiles, one prokaryotic (seld) and one mixed eukaryotic-prokaryotic (SPS). Selenoprofiles removes overlapping predictions from different profiles, keeping only the prediction from the profile that seems closer to the candidate sequence. As expected, the great majority of output predictions in prokaryotic genomes were from the seld profile. We will refer to the prokaryotic SPS/SelD !genes as SelD, following the most common nomenclature in literature.! To be able to inspect results by hand, and also to focus on good-quality genomes, we considered a reduced set of species. We took the prok_reference_genomes.txt list from ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/GENOME_REPORTS/, which NCBI claims to be a "small curated subset of really good and scientifically important prokaryotic genomes". We named this the prokaryotic reference set (223 species - see Supplementary Material S8). We manually curated most of the analysis in this set, while we kept automatized the !analysis on the full set.! We detected SelD proteins in 58 genomes (26.0%) in the prokaryotic reference set (figure 1 in main paper), which become 2805 (33.9%) when considering the prokaryotic full set (figure SM1.1). The difference in proportion between the two sets is due largely to the presence of genomes of very close strains in the full set, which we consider redundant. -

Characterization of the Uncommon Enzymes from (2004)

OPEN Mannosylglucosylglycerate biosynthesis SUBJECT AREAS: in the deep-branching phylum WATER MICROBIOLOGY MARINE MICROBIOLOGY Planctomycetes: characterization of the HOMEOSTASIS MULTIENZYME COMPLEXES uncommon enzymes from Rhodopirellula Received baltica 13 March 2013 Sofia Cunha1, Ana Filipa d’Avo´1, Ana Mingote2, Pedro Lamosa3, Milton S. da Costa1,4 & Joana Costa1,4 Accepted 23 July 2013 1Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology, University of Coimbra, 3004-517 Coimbra, Portugal, 2Instituto de Tecnologia Quı´mica Published e Biolo´gica, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2780-157 Oeiras, Portugal, 3Centro de Ressonaˆncia Magne´tica Anto´nio Xavier, 7 August 2013 Instituto de Tecnologia Quı´mica e Biolo´gica, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2781-901 Oeiras, Portugal, 4Department of Life Sciences, University of Coimbra, Apartado 3046, 3001-401 Coimbra, Portugal. Correspondence and The biosynthetic pathway for the rare compatible solute mannosylglucosylglycerate (MGG) accumulated by requests for materials Rhodopirellula baltica, a marine member of the phylum Planctomycetes, has been elucidated. Like one of the should be addressed to pathways used in the thermophilic bacterium Petrotoga mobilis, it has genes coding for J.C. ([email protected].) glucosyl-3-phosphoglycerate synthase (GpgS) and mannosylglucosyl-3-phosphoglycerate (MGPG) synthase (MggA). However, unlike Ptg. mobilis, the mesophilic R. baltica uses a novel and very specific MGPG phosphatase (MggB). It also lacks a key enzyme of the alternative pathway in Ptg. mobilis – the mannosylglucosylglycerate synthase (MggS) that catalyses the condensation of glucosylglycerate with GDP-mannose to produce MGG. The R. baltica enzymes GpgS, MggA, and MggB were expressed in E. coli and characterized in terms of kinetic parameters, substrate specificity, temperature and pH dependence. -

Multi-Product Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentations: a Review

fermentation Review Multi-Product Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentations: A Review José Aníbal Mora-Villalobos 1 ,Jéssica Montero-Zamora 1, Natalia Barboza 2,3, Carolina Rojas-Garbanzo 3, Jessie Usaga 3, Mauricio Redondo-Solano 4, Linda Schroedter 5, Agata Olszewska-Widdrat 5 and José Pablo López-Gómez 5,* 1 National Center for Biotechnological Innovations of Costa Rica (CENIBiot), National Center of High Technology (CeNAT), San Jose 1174-1200, Costa Rica; [email protected] (J.A.M.-V.); [email protected] (J.M.-Z.) 2 Food Technology Department, University of Costa Rica (UCR), San Jose 11501-2060, Costa Rica; [email protected] 3 National Center for Food Science and Technology (CITA), University of Costa Rica (UCR), San Jose 11501-2060, Costa Rica; [email protected] (C.R.-G.); [email protected] (J.U.) 4 Research Center in Tropical Diseases (CIET) and Food Microbiology Section, Microbiology Faculty, University of Costa Rica (UCR), San Jose 11501-2060, Costa Rica; [email protected] 5 Bioengineering Department, Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering and Bioeconomy (ATB), 14469 Potsdam, Germany; [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (A.O.-W.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-(0331)-5699-857 Received: 15 December 2019; Accepted: 4 February 2020; Published: 10 February 2020 Abstract: Industrial biotechnology is a continuously expanding field focused on the application of microorganisms to produce chemicals using renewable sources as substrates. Currently, an increasing interest in new versatile processes, able to utilize a variety of substrates to obtain diverse products, can be observed.