The General Strike in Amherst, Nova Scotia, 1919*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

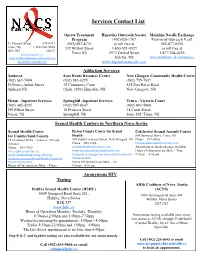

Services Contact List

Services Contact List Opiate Treatment Hepatitis Outreach Society Mainline Needle Exchange Program (902)420-1767 Provincial Outreach # call 33 Pleasant Street, 895-0931 (902) 893-4776 or toll free at 902-877-0555 Truro, NS 1 866-940-AIDS 332 Willow Street 1-800-521-0527 or toll free at B2N 3R5 (2437) [email protected] Truro NS 2973 Oxford Street 1-877-904-4555 www.northernaidsconnectionsociety.ca Halifax, NS www.mainlineneedleexchange.ca facebook.com/nacs.ns www.hepatitisoutreach.com Addiction Services Amherst- East Hants Resource Center New Glasgow Community Health Center (902) 667-7094 (902) 883-0295 (902) 755-7017 30 Prince Arthur Street 15 Commerce Court 835 East River Road Amherst,NS (Suite #250) Elmsdale, NS New Glasgow, NS Pictou - Inpatient Services Springhill -Inpatient Services Truro - Victoria Court (902) 485-4335 (902) 597-8647 (902) 893-5900 199 Elliott Street 10 Princess Street 14 Court Street, Pictou, NS Springhill, NS Suite 205, Truro, NS Sexual Health Centers in Northern Nova Scotia Sexual Health Center Pictou County Center for Sexual Colchester Sexual Assault Center for Cumberland County Health 80 Glenwood Drive, Truro, NS 11 Elmwood Drive , Amherst , NS side 503 South Frederick Street, New Glasgow, NS Phone 897-4366 entrance Phone 695-3366 [email protected] Phone 667-7500 [email protected] No website or facebook page available [email protected] www.pictoucountysexualhealth.com Hours of Operation are Mon. - Thur. www.cumberlandcounty.cfsh.info facebook.com/pages/pictou-county-centre-for- 9:30am – 4:30 pm facebook.com/page/Sexual-Health-Centre-for- Sexual-Health Cumberland-County Hours of Operation are Mon. -

Where to Go for Help – a Resource Guide for Nova Scotia

WHERE TO GO ? FOR HELP A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR NOVA SCOTIA WHERE TO GO FOR HELP A Resource Guide for Nova Scotia v 3.0 August 2018 EAST COAST PRISON JUSTICE SOCIETY Provincial Divisions Contents are divided into the following sections: Colchester – East Hants – Cape Breton Cumberland Valley – Yarmouth Antigonish – Pictou – Halifax Guysborough South Shore Contents General Phone Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 Crisis Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 HALIFAX Community Supports & Child Care Centres - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Food Banks / Soup Kitchens / Clothing / Furniture - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 17 Resources For Youth - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 20 Mental, Sexual And Physical Health - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 22 Legal Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 28 Housing Information - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Shelters / Places To Stay - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 33 Financial Assistance - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 35 Finding Work - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 36 Education Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 39 Supportive People In The Community – Hrm - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 40 Employers who do not require a criminal record check - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 41 COLCHESTER – EAST HANTS – CUMBERLAND Community Supports And Child Care Centres -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 220, NO. 4 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26, 2011 Land Transactions by the Province of Schedule “A” Nova Scotia pursuant to the Ministerial Notice of Parcel Registration under the Land Transaction Regulations (MLTR) for Land Registration Act the period February 13, 2009 to October 14, 2010 TAKE NOTICE that ownership of the property known as Name/Grantor Year Fishery Limited PID 20244828, located at 700 Willow Street, Truro, Type of Transaction Grant Colchester County, Nova Scotia, has been registered Location Hacketts Cove under the Land Registration Act, in whole or in part on Halifax County the basis of adverse possession, in the name of Allen Area 1195 square metres Dexter Symes. Document Number 92763250 recorded February 13, 2009 NOTICE is being provided as directed by the Registrar General of Land Titles in accordance with clause Name/Grantor Mariners Anchorage Residents 10(10)(b) of the Land Registration Administration Association Regulations. For further information, you may contact Type of Transaction Grant the lawyer for the registered owner, noted below. Location Glen Haven, Halifax County Area 192 square metres TO: The Heirs of Ernest MacKenzie or other persons Document Number 96826046 who may have an interest in the above-noted property. recorded September 21, 2010 DATED at Pictou, Pictou County, Nova Scotia, this Name/Grantor Welsford, Barbara 17th day of January, 2011. Type of Transaction Grant Location Oakland, Halifax County Ian H. MacLean Area 174 square metres -

Philadelphia Township Grant (Parrsboro, NS

Nova Scotia Archives Finding Aid - Philadelphia Township Grant (Parrsboro, N.S.) collection (Accession 2011-030) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.1 Printed: July 18, 2017 Language of description: English Nova Scotia Archives 6016 University Ave. Halifax Nova Scotia B3H 1W4 Telephone: (902) 424-6060 Fax: (902) 424-0628 Email: [email protected] http://archives.novascotia.ca/ https://memoryns.ca/index.php/philadelphia-township-grant-parrsboro-n-s-collection Philadelphia Township Grant (Parrsboro, N.S.) collection Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Physical condition ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Series descriptions ........................................................................................................................................... 4 - Page 2 - Accession 2011-030 Philadelphia Township Grant -

330 Pictou Antigonish Highlands Profile

A NOVA SCOTIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION Ecodistrict Profile Ecological Landscape Analysis Summary Ecodistrict 330: Pictou Antigonish Highlands An objective of ecosystem-based management is to manage landscapes in as close to a natural state as possible. The intent of this approach is to promote biodiversity, sustain ecological processes, and support the long-term production of goods and services. Each of the province’s 38 ecodistricts is an ecological landscape with distinctive patterns of physical features. (Definitions of underlined terms are included in the print and electronic glossary.) This Ecological Landscape Analysis (ELA) provides detailed information on the forest and timber resources of the various landscape components of Pictou Antigonish Highlands Ecodistrict 330. The ELA also provides brief summaries of other land values, such as minerals, energy and geology, water resources, parks and protected areas, wildlife and wildlife habitat. This ecodistrict has been described as an elevated triangle separating the Northumberland Lowlands Ecodistrict 530 of Pictou County from the St. Georges Bay Ecodistrict 520 lowlands of Antigonish County. Generally, the highlands at their summit become a rolling plateau best exemplified by The Keppoch, an area once extensively settled and farmed. The elevation in the ecodistrict is usually 210 to 245 metres above sea level and rises to 300 metres at Eigg Mountain. The total area of Pictou Antigonish Highlands is 133,920 hectares. Private land ownership accounts for 75% of the ecodistrict, 24% is under provincial Crown management, and the remaining 1% includes water bodies and transportation corridors. A significant portion of the highlands was settled and cleared for farming by Scottish settlers beginning in the late 1700s with large communities at Rossfield, Browns Mountain, and on The Keppoch. -

1 Travel to Wolfville and Kentville, Nova Scotia, Canada, to Collect

Travel to Wolfville and Kentville, Nova Scotia, Canada, to collect Vaccinium and Related Ericaceae for USDA Plant Exploration Grant 2012 Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia AAFC Kentville, Nova Scotia Kim Hummer, Research Leader USDA ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository, Corvallis, Oregon Location and Dates of Travel Wolfville and Kentville, Nova Scotia, Canada 15 July through 20 July 20102 Objectives: To obtain cuttings/ propagules of the Vaccinium collections of Dr. Sam Vander Kloet, Professor Emeritus at Acadia University, Kentville, Nova Scotia. Executive Summary During 15 through 20 July 2012, I traveled to Nova Scotia to obtain plant material that Dr. Sam Vander Kloet, Emeritus Professor at Acadia University had obtained during his life. Acadia University Conservatory, Wolfville, had about 100 accessions of subtropical Vaccinium (blueberry) and related genera. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada had about 90 accessions of native North American Vaccinium in their field collections. On Monday 16 July through Wednesday 18 July 2012, I worked at the Herbarium and Conservatory of Acadia University working with Ruth Newell, the Curator. From Wednesday afternoon through Thursday, I worked with Dr. Andrew Jamieson, Small fruit Breeder and Geneticist, Agriculture and Agri- Food Canada. I obtained a total of 654 root and stem cuttings of the following genera: Cavendishia (62), Ceratostemma (7), Costera (1), Diogenesia (9), Disterigma (10), Macleania (25), Pernettya (13), Psammisia (7), Spyrospermum (7), and Vaccinium (513). I also obtained two accessions of seed including Vaccinium boreale (1000 count) and Fragaria vesca subsp. alba (2000 count). I obtained a Canadian phytosanitary certificate and had USDA APHIS permits and letters to bring in the Vaccinium and permissible nurserystock. -

Glass Cabinet Collection

Glass Cabinet Collection The following resources are located in the New Glasgow Library. They are held in the glass cabinet in the Reference section and are not available for circulation. Patrons are welcome to come to the Library and view any of these resources. 100 years of Scotsburn : a century of growth and innovation. MacLennan, Jennifer [Scotsburn, N.S. : Scotsburn, c2000]. REFCS 334 MacL 139th Anniversary, 1817-1956, St. Andrew's Church, New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. St. Andrews Church (New Glasgow, N.S.) [S.l. : s.n.], 1956?]. REFCS 285.2716 St. A 1789: all the King's men: the story of a colonial university. DeWolf, John Mark, Flie, George. Halifax, N.S.: Alumni Association of the University of King's College, c1972 (Halifax, N.S. : McCurdy Printing.). REFCS 378.716 DeW The 1838 census index of Pictou County, Nova Scotia. McKay, Karen E. Genealogical Association of Nova Scotia. Halifax: Genealogical Society of Nova Scotia, 1995. REFCS 929 .37613 McK 1838 Pictou County, Nova Scotia census. Bridges, Steven A.Trumbull, CT : S.A. Bridges, c1987.REFCS 929.371613 Bri 1891 Census of Guysborough County, Nova Scotia, Canada Koen, Mary Elizabeth. Swampscott, Mass. : M.E. Koen, 1992. REFCS 971.621 Koe v.2, 971.621 Koe v.1 The 20th century : a trip back through the last 100 years in Pictou County, N.S. [New Glasgow, N.S.] : Evening News, 1999. REFCS 971'.613'Twe 78th Fighting Frasers in Canada : a short history of the old 78th Regiment or Fraser's Highlanders, 1757-1763. Harper, J. Ralph. Laval, Que.: Dev-Sco Publications, c1966. -

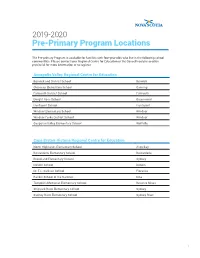

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations The Pre-primary Program is available for families with four-year-olds who live in the following school communities. Please contact your Regional Centre for Education or the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial for more information or to register. Annapolis Valley Regional Centre for Education Berwick and District School Berwick Glooscap Elementary School Canning Falmouth District School Falmouth Dwight Ross School Greenwood Hantsport School Hantsport Windsor Elementary School Windsor Windsor Forks District School Windsor Gasperau Valley Elementary School Wolfville Cape Breton-Victoria Regional Centre for Education North Highlands Elementary School Aspy Bay Boularderie Elementary School Boularderie Brookland Elementary School Sydney Donkin School Donkin Dr. T.L. Sullivan School Florence Rankin School of the Narrows Iona Tompkins Memorial Elementary School Reserve Mines Shipyard River Elementary School Sydney Sydney River Elementary School Sydney River 1 Chignecto-Central Regional Centre for Education West Colchester Consolidated School Bass River Cumberland North Academy Brookdale Great Village Elementary School Great Village Uniacke District School Mount Uniacke A.G. Baillie Memorial School New Glasgow Cobequid District Elementary School Noel Parrsboro Regional Elementary School Parrsboro Salt Springs Elementary School Pictou West Pictou Consolidated School Pictou Scotsburn Elementary School Scotsburn Tatamagouche Elementary School Tatamagouche Halifax Regional Centre for Education Sunnyside Elementary School Bedford Alderney Elementary School Dartmouth Caldwell Road Elementary School Dartmouth Hawthorn Elementary School Dartmouth John MacNeil Elementary School Dartmouth Mount Edward Elementary School Dartmouth Robert K. Turner Elementary School Dartmouth Tallahassee Community School Eastern Passage Oldfield Consolidated School Enfield Burton Ettinger Elementary School Halifax Duc d’Anville Elementary School Halifax Elizabeth Sutherland Halifax LeMarchant-St. -

Subdivision By-Law

MUNICIPALITY OF THE COUNTY OF PICTOU SUBDIVISION BY-LAW SHORT TITLE 1. This by-law may be cited as the Pictou County Subdivision By-Law and shall apply to all lands within the Municipality of the County of Pictou. INTERPRETATION 2. In this by-law, (a) “Act” means the Municipal Government Act, Stats. N.S., 1998, c. 18 and amendments thereto; (b) “area of land” means any existing lot or parcel as described by its boundaries, except in Section 8; (c) “Board” means the Nova Scotia Utility Review Board; (d) “Clerk” means the Clerk of the Municipality; (e) “Council” means the Council of the Municipality; (f) “Department of Environment and Labour” means the Nova Scotia Department of Environment and Labour, or its successor; (g) “Department of Transportation” means the Nova Scotia Department of Transportation and Public Works, or its successor; (h) “development officer” means that person appointed by Council pursuant to the Municipal Government Act and having the power and duty to administer this By-law; (i) “drainage plan” means a detailed plan of stormwater runoff and the courses and channels of it, including floodplains, for one or more parts of an area of drainage for all lands tributary to, or carrying drainage from, land that is proposed to be subdivided; (j) “existing street or highway” means any public street or public highway; (k) “in a Service Area” means wholly or partly in a Service Area or, if not, wholly or partly in a Service Area within 200 feet of an installed wastewater system existing in a Service Area at the time any application -

Ns19b Report.Pdf

Soils of Colchester County, Nova Scotia Report No. 19 Nova Scotia Soi1 Survey K.T. Webb Land Resource Research Centre Truro, Nova Scotia R.L. Thompson Nova Scotia Department of Agriculture and Marketing Truro, Nova Scotia G.J. Beke Agriculture Canada, Research Branch Lethbridge, Alberta J.L. Nowland Land Resource Research Centre Ottawa, Ontario Land Resource Research Centre Contribution No. 85-45 Accompanying map sheets: Soils of Colchester County, Nova Scotia (North, South and West sheets) Research Branch Agriculture Canada 1991 Copies of this publication area available from Nova Scotia Department of Government Services Inforination Services P.O. Box 550 Nova Scotia Agricultural College Truro, Nova Scotia B2N 3E.3 Produced by Kesearch Prograrn Service 0 Minister of Supply and Services Canada 199 1 Cat. No. A57-l51/1990E ISBS 0-662-18263-0 Correct citation for this report is as follorvs: Webb, K.T.; Thornpson, K.L.; Beke, G.J.; Norvland, J.L. 1991. Soils of Colchester County, Nova Scotia. Report No. 19 Sova Scotia Soi1 Survey. Re!iedrch Branch, Agriculture Canada, Ottawa, Ont. 201 pp. Staff Editor Jane T. Buckley CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..................................... ................vi SUMMARY/RESUME .......................................................... vii PART 1 . GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE CO UNTY ................................ 1 Location and extent ................................................. 1 History of development.............................................. 1 Population and industry ............................................ -

Pictou-Antigonish Regional Library Activity Library Board Library Visits by Location Province of Nova Scotia: Town of New Glasgow: Ms

Pictou-Antigonish Regional Library Activity Library Board Library Visits by Location Province of Nova Scotia: Town of New Glasgow: Ms. Tammy MacLaren Coun. Clyde Fraser Mr. John Blackwell, Chair 2018-2019 2019/2020 Town of Pictou: REGIONAL LIBRARY Deputy Mayor, Dan Currie Antigonish 180,670 156,859 Municipality of the County of Antigonish: Coun. Mary MacLellan Annual Report Books-By-Mail N/A N/A Library Boards of Nova Scotia Town of Stellarton: Coun. Simon Lawand New Glasgow 69,481 67,661 representative Pictou 36,400 41,049 Municipality of Pictou County: Town of Trenton: River John 9,256 12,038 Coun. Deborah Wadden Coun. Steven Stewart Stellarton 19,344 19,032 Town of Antigonish: Town of Westville: Trenton 2,756 4,966 Deputy Mayor, Willie Cormier Coun. Lynn MacDonald Westville 11,544 18,956 Population Served 64,369 Total Holdings 149,327 Summer Reading 591 Program Participants April 2019 – March 2020 Number of staff 61 www.parl.ns.ca Library Management Staff 19/20 Income 19/20 Expenditure ERIC STACKHOUSE JESS DAVEY Provincial Grant $ 1,177,567 Salaries/Benefits $ 1,567,244 Chief Librarian/ Board Secretary Manager of Web Services Municipal Grant $ 581,663 Books & Materials $ 118,607 TRECIA SCHELL MELANIE PAULS Board Income $ 212,530 Administration $ 341,102 Community Services Librarian Community Access to Technology Coordinator TOTAL $ 1,971,760 TOTAL $ 2,026,953 GREG HAYWARD Technical Services Librarian KRISTEL FLEUREN-HUNTER Children’s Services Librarian Accumulated Deficit - $ 240,170 KAREN MACNEILL Office Manager Major Sponsors JEAN ROZEE Adopt-A-Library Literacy Program Finance Manager Friends of the Antigonish Library Friends of the River John Library Our Communities Chief Librarian’s Report 2019/2020 Chairperson’s Report 2019/2020 Pictou-Antigonish Regional Library Activity In fall of 2019 the Board approved a revised planning and priorities report The anticipated funding formula increase for the fiscal year 2020-2021was Library Use 2018/19 2019/20 prepared by staff. -

Kentville ICSP Report

An Examination of Kentville’s Environmental History A Report for the Town of Kentville Integrated Community Sustainability Planning Group, Prepared by History 3383, Canadian Environmental History Supervised by Dr. David F. Duke Acadia University January 2010 Formatted by Laura Churchill Duke Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................ ii PART 1: HUMANS ................................................................................................... 1. Kentville Sanitary Sewage Management ...................................................... 1 2. Storm and Surface Water Management ..................................................... 10 3. Traffic and Transport ..................................................................................... 19 Summary Executive 4. Abandoned Industrial Sites in the Town of Kentville ............................. 30 5. Quarrying and Dumping in Kentville and its Environs .......................... 43 6. Recreational Spaces in Kentville .................................................................. 55 PART 2: NATURE .................................................................................................... 7. Domestic Water Supply and Protection in the Town of Kentville ....... 68 8. Severe Weather and Kentville; a History ................................................... 82 9. The History of the Kentville Floodplain .................................................. 100 PART 3: SURROUNDINGS .................................................................................