Underdevelopment and the Structural Origins of Antigonish Movement Co-Operatives in Eastern Nova Scotia*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Geological Record

The Geological Record Volume 3, No. 1 Winter 2016 Mineral Incentive Program Helps In This Issue Prospectors with Marketing Mineral Incentive Program Helps The Nova Scotia Mineral Incentive Program provided $110,000 in funding to Prospectors with Marketing prospectors for exploration in 2015. The program also supports prospectors with marketing and promotional activities, including attendance at mining and investment Mineral Development Proceeds under conferences such as the Mineral Exploration Roundup in Vancouver and the Tough Economic Conditions Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) conference in Toronto. Global Geopark Proposed for Parrsboro So far this year the Marketing Grant Committee has received some very good Shore Area applications, and will be providing funds and booth space to the prospectors and projects listed below. Cobequid Highlands and Cape Breton Ted MacNaughton: Long Lake molybdenum-tungsten target. This granophile Island Focus of Mineral Promotion at PDAC 2016 element prospect is a result of late-stage leucocratic greisen development in the South Mountain granite. The site features ore-grade levels of tin, bismuth, lithium Meet the Mining ‘One Window’ Standing and silver, as well as molybdenum and tungsten. Committee Bob Stewart: The Kell’s copper showing on the eastern Chedabucto Fault Zone Atlantic Geoscience Society Annual is the epicenter of some great IOCG indicator minerals in the area, including copper, Colloquium and General Meeting 2016 barite, specular hematite, siderite, ankerite and gold. Perry MacKinnon: The former Stirling VMS Mine has a new drilling target on From the Mineral Inventory Files the northern extension of the mine. This polymetallic mine, hosting silver and gold as well as (mostly) zinc, could be coupled with the nearby Lime Hill zinc prospect to New Mineral Resource Land-use Interactive Web Mapping Application produce ore from two sources. -

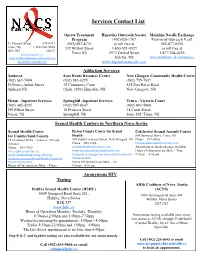

Services Contact List

Services Contact List Opiate Treatment Hepatitis Outreach Society Mainline Needle Exchange Program (902)420-1767 Provincial Outreach # call 33 Pleasant Street, 895-0931 (902) 893-4776 or toll free at 902-877-0555 Truro, NS 1 866-940-AIDS 332 Willow Street 1-800-521-0527 or toll free at B2N 3R5 (2437) [email protected] Truro NS 2973 Oxford Street 1-877-904-4555 www.northernaidsconnectionsociety.ca Halifax, NS www.mainlineneedleexchange.ca facebook.com/nacs.ns www.hepatitisoutreach.com Addiction Services Amherst- East Hants Resource Center New Glasgow Community Health Center (902) 667-7094 (902) 883-0295 (902) 755-7017 30 Prince Arthur Street 15 Commerce Court 835 East River Road Amherst,NS (Suite #250) Elmsdale, NS New Glasgow, NS Pictou - Inpatient Services Springhill -Inpatient Services Truro - Victoria Court (902) 485-4335 (902) 597-8647 (902) 893-5900 199 Elliott Street 10 Princess Street 14 Court Street, Pictou, NS Springhill, NS Suite 205, Truro, NS Sexual Health Centers in Northern Nova Scotia Sexual Health Center Pictou County Center for Sexual Colchester Sexual Assault Center for Cumberland County Health 80 Glenwood Drive, Truro, NS 11 Elmwood Drive , Amherst , NS side 503 South Frederick Street, New Glasgow, NS Phone 897-4366 entrance Phone 695-3366 [email protected] Phone 667-7500 [email protected] No website or facebook page available [email protected] www.pictoucountysexualhealth.com Hours of Operation are Mon. - Thur. www.cumberlandcounty.cfsh.info facebook.com/pages/pictou-county-centre-for- 9:30am – 4:30 pm facebook.com/page/Sexual-Health-Centre-for- Sexual-Health Cumberland-County Hours of Operation are Mon. -

Where to Go for Help – a Resource Guide for Nova Scotia

WHERE TO GO ? FOR HELP A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR NOVA SCOTIA WHERE TO GO FOR HELP A Resource Guide for Nova Scotia v 3.0 August 2018 EAST COAST PRISON JUSTICE SOCIETY Provincial Divisions Contents are divided into the following sections: Colchester – East Hants – Cape Breton Cumberland Valley – Yarmouth Antigonish – Pictou – Halifax Guysborough South Shore Contents General Phone Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 Crisis Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 HALIFAX Community Supports & Child Care Centres - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Food Banks / Soup Kitchens / Clothing / Furniture - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 17 Resources For Youth - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 20 Mental, Sexual And Physical Health - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 22 Legal Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 28 Housing Information - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Shelters / Places To Stay - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 33 Financial Assistance - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 35 Finding Work - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 36 Education Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 39 Supportive People In The Community – Hrm - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 40 Employers who do not require a criminal record check - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 41 COLCHESTER – EAST HANTS – CUMBERLAND Community Supports And Child Care Centres -

In This Document an Attempt Is Made to Present an Introduction to Adult Board. Reviews the Entire Field of Adult Education. Also

rn DOCUMENT RESUME ED 024 875 AC 002 984 By-Kidd. J. R., Ed Adult Education in Canada. Canadian Association for Adult Education, Toronto (Ontario). Pub Date SO Note- 262p. EDRS Price MF-$1.00 HC-$13.20 Descriptors- *Adult Education Programs. *Adult Leaders, Armed Forces, Bibliographies, BroadcastIndustry, Consumer Education, Educational Radio, Educational Trends, Libraries, ProfessionalAssociations, Program Descriptions, Public Schools. Rural Areas, Universities, Urban Areas Identifier s- *Canada Inthis document an attempt is made to present an introduction toadult education in Canada. The first section surveys the historical background, attemptsto show what have been the objectives of this field, and tries to assessits present position. Section IL which focuses on the relationship amongthe Canadian Association for Adult Education, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and theNational Film Board. reviews the entirefield of adult education. Also covered are university extension services. the People's Library of Nova Scotia,and the roles of schools and specialized organizations. Section III deals1 in some detail, with selected programs the 'Uncommon Schools' which include Frontier College, and BanffSchool of Fine Arts, and the School .of Community Programs. The founders, sponsors, participants,and techniques of Farm Forum are reported in the section on radio andfilms, which examines the origins1 iDurpose, and background for discussionfor Citizens' Forum. the use of documentary films inadult education; Women's Institutes; rural programs such as the Antigonish Movement and theCommunity Life Training Institute. A bibliography of Canadian writing on adult education is included. (n1) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE i PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 220, NO. 4 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26, 2011 Land Transactions by the Province of Schedule “A” Nova Scotia pursuant to the Ministerial Notice of Parcel Registration under the Land Transaction Regulations (MLTR) for Land Registration Act the period February 13, 2009 to October 14, 2010 TAKE NOTICE that ownership of the property known as Name/Grantor Year Fishery Limited PID 20244828, located at 700 Willow Street, Truro, Type of Transaction Grant Colchester County, Nova Scotia, has been registered Location Hacketts Cove under the Land Registration Act, in whole or in part on Halifax County the basis of adverse possession, in the name of Allen Area 1195 square metres Dexter Symes. Document Number 92763250 recorded February 13, 2009 NOTICE is being provided as directed by the Registrar General of Land Titles in accordance with clause Name/Grantor Mariners Anchorage Residents 10(10)(b) of the Land Registration Administration Association Regulations. For further information, you may contact Type of Transaction Grant the lawyer for the registered owner, noted below. Location Glen Haven, Halifax County Area 192 square metres TO: The Heirs of Ernest MacKenzie or other persons Document Number 96826046 who may have an interest in the above-noted property. recorded September 21, 2010 DATED at Pictou, Pictou County, Nova Scotia, this Name/Grantor Welsford, Barbara 17th day of January, 2011. Type of Transaction Grant Location Oakland, Halifax County Ian H. MacLean Area 174 square metres -

Antigonish Floodrisk and Erosion Climate Change Project

Antigonish Floodrisk and Erosion Climate Change Project The study commissioned by the Nova Scotia Department of Regional Economic Development and the Nova Scotia Department of the Environment By Dr. Tim Webster, Katie LeBlanc and Nathan Crowell Applied Geomatics Research Group, Centre of Geographic Science Nova Scotia Community College Middleton, NS B0S 1M0 & Acadia University, Wolfville, NS 1 Executive Summary The Canadian coastlines have been assessed for sensitivity to future sea-level change and it has been determined that the east coast of Canada is highly vulnerable to erosion and flooding. The third assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicates that there will be an increase in mean global sea-level from 1990 to 2100 between 0.09 m and 0.88 m (Church et al. 2001). The latest IPCC Assessment Report 4 (AR4) has projected global mean seal-level to rise between 0.18 and 0.59 m from 1990 to 2095 (Meehl et al. 2007). However as Forbes et al. (2009) point out, these projections do not account for the large ice sheets melting and measurements of actual global sea-level rise are higher than the previous predictions of the third assessment report. Rhamstorf et al. (2007) compared observed global sea-level rise to that projected in the third assessment report and found it exceeded the projections and have suggested a rise between 0.5 and 1.4 m from 1990 to 2100. Thus, Forbes et al. (2009) use the upper limit of 1.3 m as a precautionary approach to sea-level rise projections in the Halifax region. -

Accessibility Meeting Minutes August 8, 2019 Town Council Chambers

Accessibility Meeting Minutes August 8, 2019 Town Council Chambers Present Deputy Mayor D. MacInnis Mayor L. Boucher Councillor M. Farrell P. Dec, Planner (EDPC) G. Kell G. Mattie Also Present G. Post, Executive Director of the Accessibility Directorate Councilor W. Cormier Councilor A. Murray Councilor D. Roberts J. Lawrence, CAO M. Barkhouse, Director of Corporate Services S. Scannell, Director of Community Development S. Smith, Bylaw Enforcement Officer E. Stephenson, Active Living Coordinator K. Gorman, Marketing and Communication Officer L. Basinger, Strategic Initiatives Coordinator Warden O. McCarron (Antigonish County) Councillor M. MacLellan (Antigonish County) Alex Dunphy, Planner (EDPC) The meeting was called to order at 1:03pm by the Chair, Deputy Mayor D. MacInnis. Mayor L. Boucher introduced Mr. G. Post, Executive Director of the Accessibility Directorate noting his commitment to improving accessibility in the province. Round table introductions took place. G. Post provided a presentation about Access by Design. He noted the Act is about preventing and removing barriers including physical, communication, attitude, institutional, and lack of awareness. A road map is available online for Access by Design, providing guidance on how to make a community accessible by 2030. Those in attendance were advised that the Province has a grant program through Communities Culture and Heritage that will fund up to two thirds of the costs to make businesses more accessible. This funding isn’t just for the built environment but also for things like upgrading business website to accommodate visual impairment, installing hearing aid amplifiers in large meeting rooms, or printing new menus in braille. G. Post noted that there is a requirement for all municipalities to develop an accessibility plan. -

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island 381 a Different View from The

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island A different view from the sea: placenaming on Cape Breton Island William Davey Cape Breton University Sydney NS Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT : George Story’s paper A view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming suggests that there are other, complementary methods of collection and analysis than those used by his colleague E. R. Seary. Story examines the wealth of material found in travel accounts and the knowledge of fishers. This paper takes a different view from the sea as it considers the development of Cape Breton placenames using cartographic evidence from several influential historic maps from 1632 to 1878. The paper’s focus is on the shift names that were first given to water and coastal features and later shifted to designate settlements. As the seasonal fishing stations became permanent settlements, these new communities retained the names originally given to water and coastal features, so, for example, Glace Bay names a town and bay. By the 1870s, shift names account for a little more than 80% of the community names recorded on the Cape Breton county maps in the Atlas of the Maritime Provinces . Other patterns of naming also reflect a view from the sea. Landmarks and boundary markers appear on early maps and are consistently repeated, and perimeter naming occurs along the seacoasts, lakes, and rivers. This view from the sea is a distinctive quality of the island’s names. Keywords: Canada, Cape Breton, historical cartography, island toponymy, placenames © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction George Story’s paper The view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming “suggests other complementary methods of collection and analysis” (1990, p. -

150 Books of Influence Editor: Laura Emery Editor: Cynthia Lelliott Production Assistant: Dana Thomas Graphic Designer: Gwen North

READING NOVA SCOTIA 150 Books of Influence Editor: Laura Emery Editor: Cynthia Lelliott Production Assistant: Dana Thomas Graphic Designer: Gwen North Cover photo and Halifax Central Library exterior: Len Wagg Below (left to right):Truro Library, formerly the Provincial Normal College for Training Teachers, 1878–1961: Norma Johnson-MacGregor Photos of Halifax Central Library interiors: Adam Mørk READING NOVA SCOTIA 150 Books of Influence A province-wide library project of the Nova Scotia Library Association and Nova Scotia’s nine Regional Public Library systems in honour of the 150th anniversary of Confederation. The 150 Books of Influence Project Committee recognizes the support of the Province of Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage to develop and promote our cultural resources for all Nova Scotians. Final publication date November 2017. Books are our finest calling card to the world. The stories they share travel far and wide, and contribute greatly to our global presence. Books have the power to profoundly express the complex and rich cultural life that makes Nova Scotia a place people want to visit, live, work and play. This year, the 150th Anniversary of Confederation provided Public Libraries across the province with a unique opportunity to involve Nova Scotians in a celebration of our literary heritage. The value of public engagement in the 150 Books of Influence project is demonstrated by the astonishing breadth and quality of titles listed within. The booklist showcases the diversity and creativity of authors, both past and present, who have called Nova Scotia home. -

Locating the Contributions of the African Diaspora in the Canadian Co-Operative Sector

International Journal of CO-OPERATIVE ACCOUNTING AND MANAGEMENT, 2020 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 3 DOI: 10.36830/IJCAM.202014 Locating the Contributions of the African Diaspora in the Canadian Co-operative Sector Caroline Shenaz Hossein, Associate Professor of Business & Society, York University, Canada Abstract: Despite Canada’s legacy of co-operativism, Eurocentrism dominates thinking in the Canadian co- op movement. This has resulted in the exclusion of racialized Canadians. Building on Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s (2014) exposure of the historical fact of African Americans’ alienation from their own cooperativism as well as the mainstream coop movement, I argue that Canadian co-operative studies are limited in their scope and fail to include the contributions of Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC). I also argue that the discourses of the Anglo and Francophone experiences dominate the literature, with mainly white people narrating the Indigenous experience. Finally, I hold that the definition of co-operatives that we use in Canada should include informal as well as formal co-operatives. Guyanese economist C.Y. Thomas’ (1974) work has influenced how Canadians engage in co-operative community economies. However, the preoccupation with formally registered co-operatives excludes many BIPOC Canadians. By only recounting stories about how Black people have failed to make co-operatives “successful” financially, the Canadian Movement has missed many stories of informal co-operatives that have been effective in what they set out to do. Expanding what we mean by co-operatives for the Canadian context will better capture the impact of co-operatives among BIPOC Canadians. Caroline Shenaz Hossein is Associate Professor of Business & Society in the Department of Social Science at York University in Toronto, Canada. -

The Public Archives of Nova Scotia C

Document generated on 09/27/2021 8:31 a.m. Acadiensis The Public Archives of Nova Scotia C. Bruce Fergusson Volume 2, Number 1, Autumn 1972 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/acad2_1arc01 See table of contents Publisher(s) The Department of History of the University of New Brunswick ISSN 0044-5851 (print) 1712-7432 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Fergusson, C. B. (1972). The Public Archives of Nova Scotia. Acadiensis, 2(1), 71–81. All rights reserved © Department of History at the University of New This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Brunswick, 1972 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Acadiensis 71 Archives The Public Archives of Nova Scotia As one of the earliest settled of the provinces, and holding primacy in political affairs in this country in the introduction of representative and responsible government alike, it is fitting that Nova Scotia should have the longest contin uous governmental archival institution in Canada. From its romantic age to its recent growth, Nova Scotia, rich, vivid, and colorful in tradition, has had a vibrant and fascinating history, but although Nova Scotia has been relatively rich in the wealth of its historical material, the condition of its public records and historical documents left much to be desired over long stretches of time. -

Antigonish County

Clean Foundation Northumberland Strait Coastal Restoration Project Tidal Crossing Assessments – Antigonish County 126 Portland St • Dartmouth, NS • B2Y 1H8 • Phone: (902) 420-3474 i Northumberland Straight Costal Restoration Project Antigonish County Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 SITE DESCRIPTIONS .............................................................................................................................. 4 Antigonish Landing .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Captains Pond ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Frasers Marsh ...................................................................................................................................................... 12 Mahoneys Beach ................................................................................................................................................. 16 Southside Harbour............................................................................................................................................