Downloads/Dynamic/Reginavabdullahbaybasincase.Pdf, Accessed 6 June 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Study of White Collar Crime Prosecution in the United States and the United Kingdom Daniel Huynh

Journal of International Business and Law Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 5 2010 Preemption v. Punishment: A Comparative Study of White Collar Crime Prosecution in the United States and the United Kingdom Daniel Huynh Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/jibl Recommended Citation Huynh, Daniel (2010) "Preemption v. Punishment: A Comparative Study of White Collar Crime Prosecution in the United States and the United Kingdom," Journal of International Business and Law: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/jibl/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International Business and Law by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Huynh: Preemption v. Punishment: A Comparative Study of White Collar Cri PREEMPTION V. PUNISHMENT: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF WHITE COLLAR CRIME PROSECUTION IN THE UNITED STATES AND THE UNITED KINGDOM Daniel Huynh * I. INTRODUCTION Compared to most types of crime, white collar crime is a relatively new phenomenon. After several high profile cases in the mid-1900's in the United States, white collar crime emerged into the national spotlight. The idea materialized that there should be a separate and distinct category of crime aside from the everyday common crimes, like murder or burglary. More recently, large-scale scandals and frauds have been uncovered worldwide -

University of Birmingham Teaching the Elements of Crimes

University of Birmingham Teaching the elements of crimes Child, John License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Child, J 2016, Teaching the elements of crimes. in K Gledhill & B Livings (eds), The teaching of criminal law: the pedagogical imperatives. Legal Pedagogy, Taylor & Francis. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge/CRC Press in The Teaching of Criminal Law:The pedagogical imperatives, 1st Edition on 08/09/2016, available online: https://www.routledge.com/The-Teaching-of-Criminal-Law-The-pedagogical- imperatives/Gledhill-Livings/p/book/9781138841994 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

Fifth Report of the Independent Monitoring Commission

FIFTH REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT MONITORING COMMISSION Presented to the Government of the United Kingdom and the Government of Ireland under Articles 4 and 7 of the International Agreement establishing the Independent Monitoring Commission Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 24th May 2005 HC 46 LONDON: The Stationery Office £17.00 © Parliamentary Copyright 2005 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Parliamentary copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St. Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or email: [email protected] Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Dd PC1405 C7 05/05 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Context 2. Paramilitary Groups: Assessment of Current Activities 3. Paramilitary Groups: The Incidence of Violence and Exiling 4. The Murder of Robert McCartney 5. Paramilitary Groups: The Activities of Prisoners Released under the Belfast Agreement 6. Paramilitary Groups: Organised Crime and Other Paramilitary Activity 7. Responding to Paramilitary Groups: Some Other Issues 8. Paramilitary Groups: Leadership 9. Conclusions and Recommendations 3 ANNEXES I Articles 4 and 7 of the International Agreement II The IMC’s Guiding Principles III Summary of Measures provided for in UK Legislation which may be recommended for action by the Northern Ireland Assembly by the Independent Monitoring Commission (IMC) 4 1. -

Assets Recovery Agency Resource Accounts 2004-05

Presented pursuant to GRA Act 2000 c20. s.6 Assets Recovery Agency Resource Accounts 2004-05 (For the year ended 31 March 2005) Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 20 July 2005 LONDON: The Stationery Office 20 July 2005 HC 190 £9.10 Assets Recovery Agency Resource Accounts 2004-05 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ANNUAL REPORT 3 Departmental Aims and Objectives 3 Where the money goes 4 Financial Review 4 Going Concern 6 Accounting Officer of the Agency and Management Board 6 Appointment of Accounting Officer and Management Board 7 Prompt Payment Policy 7 Interest Rate and Currency Risk 7 Fixed Assets 7 Health and Safety 7 Equality and Diversity 7 Employment of Disabled Persons 8 Employee Relations 8 Auditors 8 The Future 8 Cost commitments 8 Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 9 International 9 STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTING OFFICER’S RESPONSIBILITIES 10 STATEMENT ON INTERNAL CONTROL 11 THE CERTIFICATE AND REPORT OF THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL TO THE HOUSE OF COMMONS 14 SCHEDULE 1 16 SCHEDULE 2 18 SCHEDULE 3 19 SCHEDULE 4 20 SCHEDULE 5 21 NOTES TO THE ACCOUNTS 22 1. Statement of accounting policies 22 1.1 Accounting convention 22 1.2 Tangible fixed assets 22 1.3 Depreciation 22 1.4 Intangible Assets 22 1.5 Donated Assets 22 1.6 Research and development 22 1.7 Operating income 22 1.8 Administration and programme expenditure 23 1.9 Capital charge 23 1.10 Leases 23 1.11 Pensions 23 1.12 Value Added Tax 23 1.13 Confiscated Assets 23 2. -

Asset Recovery Agency: Proceeds of Crime

RESEARCH AND LIBRARY SERVICES Northern Ireland Assembly SSET ECOVERY GENCY ROCEEDS OF RIME A R A : P C SUMMARY OF KEY POINTS • The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 contains UK wide measures in relation to confiscation of the proceeds of crime. • Any sums received by the Secretary of State in consequence of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 are to be paid into the consolidated fund • In Scotland, Scotland Ministers are the enforcement authority • Cashback for Communities programme was launched by, and is the responsibility of, the Justice Minister and the related Government Department in Scotland; money must be invested in projects that alleviate the effects of crime • Arts and Culture strand of Cashback for Communities is administered by Arts and Business Scotland. • If more than £17 million is recovered in any financial year in Scotland the balance is sent back to the UK Treasury • The Asset Recovery Agency (ARA) in Northern Ireland was created in February 2003 and existed until April 2008 • The ARA collected £23 million while it was in operation • ARA merged with the Serious Organised Crime Agency in 2008 – forming an organisation with a UK wide remit. • Policing and Criminal law are devolved in Scotland but are not devolved in Northern Ireland. PROCEEDS OF CRIME ACT (UK) 2002 1 The Proceed of Crime Act 2002 contains a package of measures relating to confiscation of the proceeds of crime. This Act applies across the UK. Scotland: Proceeds of Crime Act In Scotland, the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 builds upon the criminal confiscation scheme which was set out in the Proceeds of Crime (Scotland) Act 1995, and consolidates and strengthens money laundering offences. -

Robbery Definitive Guideline

Robbery Definitive Guideline GUIDELINE DEFINITIVE Contents Applicability of guideline 2 Robbery – street and less sophisticated commercial 3 Theft Act 1968 (section 8(1)) Robbery – professionally planned commercial 9 Theft Act 1968 (section 8(1)) Robbery – dwelling 15 Theft Act 1968 (section 8(1)) © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Effective from 1 April 2016 2 Robbery Definitive Guideline Applicability of guideline n accordance with section 120 of the Coroners Structure, ranges and starting points and Justice Act 2009, the Sentencing Council For the purposes of section 125(3)–(4) of the Iissues this definitive guideline. It applies Coroners and Justice Act 2009, the guideline to all offenders aged 18 and older, who are specifies offence ranges – the range of sentences sentenced on or after 1 April 2016, regardless of appropriate for each type of offence. Within each the date of the offence. offence, the Council has specified a number of categories which reflect varying degrees of Section 125(1) of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 seriousness. The offence range is split into category provides that when sentencing offences committed ranges – sentences appropriate for each level after 6 April 2010: of seriousness. -

Rules in Relation to Disclosure of Spent Convictions

A Summary of the Changes in Relation to Disclosure of Spent Convictions The Key Change to the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974: The removal of the legal requirement for all spent convictions to be self-disclosed by an individual so as to ensure only relevant spent convictions are required to be self-disclosed. In other words, the amendment Order restricts the requirement for self-disclosure. Unspent Convictions The disclosure of unspent convictions will not change. Spent Convictions The disclosure of certain spent conviction information will change. The decision about whether or not a spent conviction should be disclosed will be determined by the Legal Adviser prior to the Committee hearing. As the rules are prescriptive there is no need for either the Committee or the Legal Adviser to exercise discretion. A spent conviction will be disclosed or it will not. The disclosure of spent convictions will be determined by reference to one of three categories: Category 1 – Offences which must always be disclosed (Appendix 1 list) A list of such offences which must always be disclosed has been developed. It is generally offences that are more serious in nature. The list is prescriptive. Category 2 – Offences which are to be disclosed subject to rules (‘the rules list’) (Appendix 2 list) Again a prescriptive list of offences has been developed for this category. If an offence is on this list then consideration will be given to the age of the conviction and the age of the person at the time of conviction. The following table relates to convictions on the ‘rules list’ Age at Conviction Period of disclosure Treatment 18 years or older 15 years No disclosure after 15 years Younger than 18 years 7.5 years No disclosure after 7.5 years This means that a conviction on the ‘rules list’ will not be disclosed if it is over 15 years old for adults or 7.5 years for people aged under 18 years when convicted. -

Overarching Impact Assessment Has Been Developed to Provide an Overview of the Main Provisions of the Bill

Summary: Analysis & Evidence Policy Option 2 Description: FULL ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT Price Base PV Base Time Period Net Benefit (Present Value (PV)) (£m) Year Year Years Low: Optional High: Optional Best Estimate: COSTS (£m) Total Transition Average Annual Total Cost (Constant Price) Years (excl. Transition) (Constant Price) (Present Value) Low Optional Optional Optional High Optional Optional Optional Best Estimate Description and scale of key monetised costs by „main affected groups‟ Monetised costs for the main provisions are detailed in the individual impact assessments. In summary, the provisions of the Bill impact mainly on the public sector, in particular: the NCA, police forces (in the United Kingdom), local authorities, the Crown Prosecution Service (in England and Wales), the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (in Scotland), the Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland, the courts (in the UK) and prison and probation services (in the UK). Other key non-monetised costs by „main affected groups‟ A number of public bodies will be required to make administrative changes in relation to the provisions in the Bill. These non-monetarised costs are also detailed in individual impact assessments. BENEFITS (£m) Total Transition Average Annual Total Benefit (Constant Price) Years (excl. Transition) (Constant Price) (Present Value) Low Optional Optional Optional High Optional Optional Optional Best Estimate Description and scale of key monetised benefits by „main affected groups‟ Full details of the key monetarised benefits are detailed in individual impact assessments. Other key non-monetised benefits by „main affected groups‟ The provisions of the Bill have the potential to improve protection of the public. These non-monetarised benefits by the main affected groups are detailed in indivudal impact assessments. -

Memorandum to the Committee of Public Accounts from the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland: Combating Organised Crime

Memorandum to the Committee of Public Accounts from the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland: Combating organised crime Memorandum to the Committee of Public Accounts from the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland: Combating organised crime BELFAST: The Stationery Office This Memorandum and detailed Note which accompanies it have been prepared under Article 8 of the Audit (Northern Ireland) Order 1987 for presentation to the Northern Ireland Assembly in accordance with Article 11 of that Order. KJ Donnelly Northern Ireland Audit Office Comptroller and Auditor General 19th January 2010 The Comptroller and Auditor General is the head of the Northern Ireland Audit Office employing some 145 staff. He, and the Northern Ireland Audit Office are totally independent of Government. He certifies the accounts of all Government Departments and a wide range of other public sector bodies; and he has statutory authority to report to the Assembly on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which departments and other bodies have used their resources. For further information about the Northern Ireland Audit Office please contact: Northern Ireland Audit Office 106 University Street BELFAST BT7 1EU Tel: 028 9025 1100 email: [email protected] website: www.niauditoffice.gov.uk © Northern Ireland Audit Office 2009 Memorandum to the Committee of Public Accounts from the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland: Combating organised crime Contents Introduction 2 - 3 The scale and nature of organised crime in Northern Ireland 3 - 7 Actions taken so far and areas for further consideration 8 - 14 Annex 1: Terms of reference 16 Annex 2: Progress in implementing relevant NIAC recommendationson 17 - 33 Annex 3: List of bodies consulted 34 - 35 List of abbreviations 36 Introduction 2 Memorandum to the Committee of Public Accounts from the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland: Combating organised crime Introduction 1. -

Violence Against the Person

Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Violence against the Person Homicide Death or Serious Injury – Unlawful Driving Violence with injury Violence without injury Stalking and Harassment All Counting Rules enquiries should be directed to the Force Crime Registrar Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Homicide Classification Rules and Guidance 1 Murder 4/1 Manslaughter 4/10 Corporate Manslaughter 4/2 Infanticide All Counting Rules enquiries should be directed to the Force Crime Registrar Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Homicide – Classification Rules and Guidance (1 of 1) Classification: Diminished Responsibility Manslaughter Homicide Act 1957 Sec 2 These crimes should not be counted separately as they will already have been counted as murder (class 1). Coverage Murder Only the Common Law definition applies to recorded crime. Sections 9 and 10 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 give English courts jurisdiction where murders are committed abroad, but these crimes should not be included in recorded crime. Manslaughter Only the Common Law and Offences against the Person Act 1861 definitions apply to recorded crime. Sections 9 and 10 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 gives courts jurisdiction where manslaughters are committed abroad, but these crimes should not be included in recorded crime. Legal Definitions Corporate Manslaughter and Homicide Act 2007 Sec 1(1) “1 The offence (1) An organisation to which this section applies is guilty of an offence if the way in which its activities are managed or organised - (a) causes a person’s death, and (b) amounts to a gross breach of a relevant duty of care owed by the organisation to the deceased.” Capable of Being Born Alive - Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 Capable of being born alive means capable of being born alive at the time the act was done. -

The Practitioner's Guide to Global Investigations

GIR Global Investigations Review The Practitioner’s Guide to Global Investigations Second Edition Editors Judith Seddon, Clifford Chance Eleanor Davison, Fountain Court Chambers Christopher J Morvillo, Clifford Chance Michael Bowes QC, Outer Temple Chambers Luke Tolaini, Clifford Chance 2018 v The Practitioner’s Guide to Global Investigations Second Edition Editors: Judith Seddon Eleanor Davison Christopher J Morvillo Michael Bowes QC Luke Tolaini Publisher David Samuels Senior Co-Publishing Business Development Manager George Ingledew Project Manager Edward Perugia Editorial Coordinator Iain Wilson Head of Production Adam Myers Senior Production Editor Simon Busby Copy-editor Jonathan Allen Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 2017 Law Business Research Ltd www.globalinvestigationsreview.com No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided is accurate as of November 2017, be advised that this is a developing area. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to the Project Manager: [email protected]. Enquiries concerning editorial content should be directed -

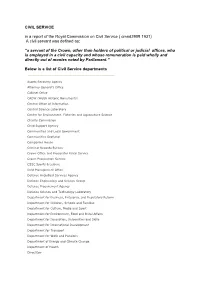

CIVIL SERVICE in a Report of the Royal Commission on Civil Service ( Cmnd3909 1931) a Civil Servant Was Defined As

CIVIL SERVICE in a report of the Royal Commission on Civil Service ( cmnd3909 1931) A civil servant was defined as: “a servant of the Crown, other than holders of political or judicial offices, who is employed in a civil capacity and whose remuneration is paid wholly and directly out of monies voted by Parliament.” Below is a list of Civil Service departments Assets Recovery Agency Attorney General’s Office Cabinet Office CADW (Welsh Historic Monuments) Central Office of Information Central Science Laboratory Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science Charity Commission Child Support Agency Communities and Local Government Communities Scotland Companies House Criminal Records Bureau Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service Crown Prosecution Service CSSC Sports & Leisure Debt Management Office Defence Analytical Services Agency Defence Engineering and Science Group Defence Procurement Agency Defence Science and Technology Laboratory Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Department for Children, Schools and Families Department for Culture, Media and Sport Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills Department for International Development Department for Transport Department for Work and Pensions Department of Energy and Climate Change Department of Health DirectGov Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency Driving Standards Agency Estyn (HM Inspectorate for Education and Training in Wales) Export Credits Guarantee Department Fire Service College Fisheries