The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juno Talent: Ellen Page, Jennifer Garner, Jason Bateman, Michael Cera, Alison Janney, J. K. Simmons, Olivia Thirlby. Date Of

Juno Talent: Ellen Page, Jennifer Garner, Jason Bateman, Michael Cera, Alison Janney, J. K. Simmons, Olivia Thirlby. Date of review: Thursday 13th December, 2007 Director: Jason Reitman Duration: 91 minutes Classification: M We rate it: 4 and a half stars. Jason Reitman, son of ultra-mainstream (and very successful) Hollywood director Ivan Reitman (he of Ghostbusters, Stripes and Kindergarten Cop fame) may just be able to move out from under his father’s significant shadow with this wonderful film. Jason Reitman’s breakthrough film as a director was 2005’s Thank You for Smoking, a cleverly written and very well performed black comedy that was so well pulled-off that one felt in the presence of promising new talent. It seems that feeling was correct, because with Juno, a very different film to its predecessor, Reitman has made an utterly assured and charming comedy/drama, and has drawn tremendously convincing and engaging performances from the entire cast. The talented young actress Ellen Page (who was so memorable in the confronting thriller Hard Candy) plays the titular character, an intelligent, articulate, out-of-left- field high-school student who, as our story opens, finds herself pregnant to her close friend and would-be boyfriend, Bleeker. Being smart, strong and self-possessed, Juno confronts her situation level-headedly, and decides, on reflection, that she will go through with the pregnancy and offer her child for adoption to a couple who are unable to conceive. With the support of her family - stepmother Bren (the wonderful Alison Janney) and father Mac (the ever-humourous J. -

Description of the Tobacco Market, Manufacturing of Cigarettes and the Market of Related Non-Tobacco Products

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 21 December 2012 THE EUROPEAN UNION 18068/12 Interinstitutional File: ADD 3 2012/0366 (COD) SAN 337 MI 850 FISC 206 CODEC 3117 COVER NOTE from: Secretary-General of the European Commission, signed by Mr Jordi AYET PUIGARNAU, Director date of receipt: 20 December 2012 to: Mr Uwe CORSEPIUS, Secretary-General of the Council of the European Union No Cion doc.: SWD(2012) 452 final (Part 3) Subject: COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentat ion and sale of tobacco and related products (Text with EEA relevance) Delegations will find attached Commission document SWD(2012) 452 final (Part 3). ________________________ Encl.: SWD(2012) 452 final (Part 3) 18068/12 ADD 3 JS/ic 1 DG B 4B EN EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 19.12.2012 SWD(2012) 452 final Part 3 COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products (Text with EEA relevance) {COM(2012) 788 final} {SWD(2012) 453 final} EN EN A.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE TOBACCO MARKET, MANUFACTURING OF CIGARETTES AND THE MARKET OF RELATED NON-TOBACCO PRODUCTS A.2.1. The tobacco market .................................................................................................. 1 A.2.1.1. Tobacco products .............................................................................................. 1 A.2.1.2. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

The Capitol Dome

THE CAPITOL DOME The Capitol in the Movies John Quincy Adams and Speakers of the House Irish Artists in the Capitol Complex Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way A MAGAZINE OF HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETYVOLUME 55, NUMBER 22018 From the Editor’s Desk Like the lantern shining within the Tholos Dr. Paula Murphy, like Peart, studies atop the Dome whenever either or both America from the British Isles. Her research chambers of Congress are in session, this into Irish and Irish-American contributions issue of The Capitol Dome sheds light in all to the Capitol complex confirms an import- directions. Two of the four articles deal pri- ant artistic legacy while revealing some sur- marily with art, one focuses on politics, and prising contributions from important but one is a fascinating exposé of how the two unsung artists. Her research on this side of can overlap. “the Pond” was supported by a USCHS In the first article, Michael Canning Capitol Fellowship. reveals how the Capitol, far from being only Another Capitol Fellow alumnus, John a palette for other artist’s creations, has been Busch, makes an ingenious case-study of an artist (actor) in its own right. Whether as the historical impact of steam navigation. a walk-on in a cameo role (as in Quiz Show), Throughout the nineteenth century, steam- or a featured performer sharing the marquee boats shared top billing with locomotives as (as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), the the most celebrated and recognizable motif of Capitol, Library of Congress, and other sites technological progress. -

Where Have All the Fairies Gone? Gwyneth Evans

Volume 22 | Number 1 | Issue 83, Autumn Article 4 10-15-1997 Where Have All the Fairies Gone? Gwyneth Evans Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Recommended Citation Evans, Gwyneth (1997) "Where Have All the Fairies Gone?," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Where Have All the Fairies Gone? Abstract Examines a number of modern fantasy novels and other works which portray fairies, particularly in opposition to Victorian and Edwardian portrayals of fairies. Distinguishes between “neo-Victorian” and “ecological” fairies. Additional Keywords Byatt, A.S. Possession; Crowley, John. Little, Big; Fairies in literature; Fairies in motion pictures; Jones, Terry. Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book; Nature in literature; Wilson, A.N. Who Was Oswald Fish? This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss1/4 P a g e 12 I s s u e 8 3 A u t u m n 1 9 9 7 M y t h l o r e W here Have All the Fairies Gone? G wyneth Evans As we create gods — and goddesses — in our own Crowley's Little, Big present, in their very different ways, image, so we do the fairies: the shape and character a contrast and comparison between imagined characters an age attributes to its fairies tells us something about the of a Victorian and/or Edwardian past and contemporary preconceptions, taboos, longings and anxieties of that age. -

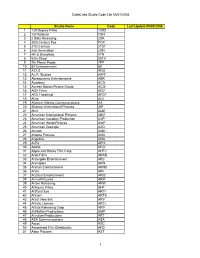

Cablelabs Studio Code List 05/01/2006

CableLabs Studio Code List 05/01/2006 Studio Name Code Last Update 05/05/2006 1 120 Degree Films 120D 2 1st National FSN 3 2 Silks Releasing 2SR 4 20th Century Fox FOX 5 21st Century 21ST 6 2nd Generation 2GN 7 4th & Broadway 4TH 8 50th Street 50TH 9 7th Planet Prods 7PP 10 8X Entertainment 8X 11 A.D.G. ADG 12 A.I.P. Studios AIPS 13 Abramorama Entertainment ABR 14 Academy ACD 15 Access Motion Picture Group ACM 16 ADV Films ADV 17 AFD Theatrical AFDT 18 Alive ALV 19 Alliance Atlantis Communications AA 20 Alliance International Pictures AIP 21 Almi ALM 22 American International Pictures AINT 23 American Vacation Production AVP 24 American World Pictures AWP 25 American Zoetrope AZO 26 Amoon AMO 27 Andora Pictures AND 28 Angelika ANG 29 A-Pix APIX 30 Apollo APO 31 Apple and Honey Film Corp. AHFC 32 Arab Films ARAB 33 Arcangelo Entertainment ARC 34 Arenaplex ARN 35 Arenas Entertainment ARNS 36 Aries ARI 37 Ariztical Entertainment ARIZ 38 Arrival Pictures ARR 39 Arrow Releasing ARW 40 Arthouse Films AHF 41 Artificial Eye ARTI 42 Artisan ARTS 43 Artist View Ent. ARV 44 Artistic License ARTL 45 Artists Releasing Corp ARP 46 ArtMattan Productions AMP 47 Artrution Productions ART 48 ASA Communications ASA 49 Ascot ASC 50 Associated Film Distribution AFD 51 Astor Pictures AST 1 CableLabs Studio Code List 05/01/2006 Studio Name Code Last Update 05/05/2006 52 Astral Films ASRL 53 At An Angle ANGL 54 Atlantic ATL 55 Atopia ATP 56 Attitude Films ATT 57 Avalanche Films AVF 58 Avatar Films AVA 59 Avco Embassy AEM 60 Avenue AVE 61 B&W Prods. -

Mrs. Stager- English 4 - All Sections

2020 Summer Assignments - Mrs. Stager- English 4 - all sections English 4 Summer Reading: Circe by Madeline Miller; available in paperback, e-book and audio book. The study guide (see link below ) is due by the first day of class and will be used to write an essay during the first few weeks of school. The novel will be used in the first unit of study in Eng 4. Link to info on the book and the study guide: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1kXsSizZNNT9eqlMFTSD7nmIVUiuiftqGgp9r7fGs5d0/edit?usp=sharing AND Every student in English 4 is required to write a first draft college application essay and share it with Mrs. Stager on Google Docs by the first day of school. Instructions: ● Select a Common App essay topic listed below OR you may write based on a prompt for a specific school to which you are applying. **NOTE: If you are writing an essay for a specific college, you must include the entire essay prompt. This will allow me to ensure you are addressing the essay prompt adequately. ● Review the rubric for complete instructions; a large part of your grade for this 1st draft is following the instructions. ● Keep in mind that this is your first draft, and we will revise once school begins; sometimes getting started is the most difficult part of the process (see below for essay tips). ● If you need a finalized essay for an application before school starts, please let me know. I will check my email a few times a week throughout the summer. DO NOT WRITE YOUR ESSAY ABOUT COVID - If you write about COVID, will ask you to re-write it. -

Monograph 21. the Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control

Monograph 21: The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control Section 6 Economic and Other Implications of Tobacco Control Chapter 15 Employment Impact of Tobacco Control 543 Chapter 15 Employment Impact of Tobacco Control Adoption and implementation of effective tobacco control policy interventions are often influenced by concerns over the potential employment impact of such policies. This chapter examines employment issues and discusses the following: . An overview of current tobacco-related employment, including employment in tobacco growing, manufacturing, wholesale and retail sales, and tobacco- expenditure-induced employment . Trends in tobacco-related employment including the shift toward low- and middle- income countries . Impact of globalization, increased workforce productivity, and new technologies on tobacco-related employment . Impact of tobacco control policies on overall employment and how this impact varies based on the type of tobacco economy in specific countries. Econometric studies show that in most countries tobacco control policies would have an overall neutral or positive effect on overall employment. In the few countries that depend heavily on tobacco exporting, global implementation of effective tobacco control policies would produce a gradual decline in employment. Around the world, employment in tobacco manufacturing has decreased primarily because of improvements in manufacturing technology, allowing more tobacco products to be manufactured by fewer workers, and by the shift from state-owned to private ownership, -

Assessing Oregon's Retail Environment

ASSESSING OREGON’S RETAIL ENVIRONMENT SHINING LIGHT ON TOBACCO INDUSTRY TACTICS If we thought the tobacco industry didn’t advertise anymore, it’s time to think again. This assessment shines light on how the industry spends over $100 million to promote its products in Oregon stores and to hook the next generation. DID YOU KNOW THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY SPENDS OVER $100 MILLION EACH YEAR *1 IN OREGON? Tobacco products are front and center, where people — including kids — will see them every day. To gauge what tobacco retail marketing looks like across the state, local health department staf and volunteers visited nearly 2,000 Oregon tobacco retailers in 2018. Data provide striking information about how the tobacco industry pushes its deadly products across Oregon. The fndings are clear: The tobacco industry is aggressively marketing to people in Oregon, and especially targets youth, communities of color and people living with lower incomes. This report outlines fndings from the retail assessment and explores ways Oregon communities can reduce tobacco marketing, help people who smoke quit, and keep youth from starting — and ultimately save thousands of Oregon lives each year. * This amount does not include spending on advertising and marketing of e-cigarettes, for which statewide data is not yet available. When added in, this number climbs even higher. THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY SPENDS BILLIONS TO RECRUIT NEW CUSTOMERS. Every year, the tobacco industry spends E-cigarette companies rapidly increased their more than $8.6 billion nationally on tobacco retail advertising from $6.4 million to $115 advertising.2 When TV and billboard advertising million nationally between 2011 and 2014 for tobacco was restricted (in 1971 and 1998, alone.4 Advertising restrictions do not apply to respectively),3 the tobacco industry shifted its e-cigarettes. -

January 2015

January 2015 HDNet Movies delivers the ultimate movie watching experience – uncut - uninterrupted – all in high definition. HDNet Movies showcases a diverse slate of box-office hits, iconic classics and award winners spanning the 1950s to 2000s. HDNet Movies also features kidScene, a daily and Friday Night program block dedicated to both younger movie lovers and the young at heart. For complete movie schedule information, visit www.hdnetmovies.com. Each Month HDNet Movies rolls out the red carpet and shines the spotlight on Hollywood Blockbusters, Award Winners and Memorable Movies th rd Always (Premiere) January 8 at 6:30pm The Missing (Premiere) January 3 at 8:00pm Starring Richard Dreyfuss, Holly Hunter, John Starring Tommy Lee Jones, Cate Blanchett, Evan Goodman, Audrey Hepburn. Directed by Steven Rachel Wood. Directed by Ron Howard. Spielberg. The Quick and the Dead January 3rd at 6:00pm Antwone Fisher (Premiere) January 2nd at 4:35pm Starring Sharon Stone, Gene Hackman, Russell Starring Derek Luke, Denzel Washington, Joy Bryant. Crowe, Leonardo DiCaprio. Directed by Sam Raimi. Directed by Denzel Washington. Tears of the Sun (Premiere) January 10th at th A Few Good Men January 10 at 6:30pm 9:00pm Starring Tom Cruise, Jack Nicholson, Demi Moore, Starring Bruce Willis, Monica Bellucci, Cole Hauser, Kevin Bacon. Directed by Rob Reiner. Tom Skerritt. Directed by Antoine Fuqua. Make kidScene your destination every day from 6:00am to 4:30pm. Check program schedule or www.hdnetmovies.com for all scheduled broadcasts. An American Tale January 1st at 6:00am Lego: The Adventures of Clutch Powers (Premiere) January 4th at 7:30am Featuring voices of: Christopher Plummer, Madeline Kahn, Dom DeLuise. -

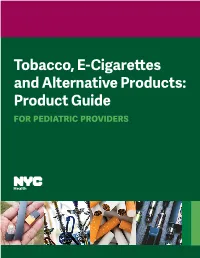

Tobacco, E-Cigarettes and Alternative Products

Tobacco, E-Cigarettes and Alternative Products: Product Guide FOR PEDIATRIC PROVIDERS Although youth use of traditional cigarettes has declined in New York City (NYC), youth have turned to other products, including cigars, smokeless tobacco, and electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). These products are often flavored (such as with menthol) and almost always contain nicotine. Flavors are concerning because they can mask the harshness of tobacco, appeal to kids, and are often directly marketed to teens and preteens. NICOTINE can change the chemistry of the adolescent brain. It may affect learning ability and worsen memory and concentration. Youth are particularly vulnerable to nicotine dependence, which can occur even with occasional use. Nicotine may also affect the way the adolescent brain processes other drugs, like alcohol, cannabis and cocaine. The following is a list of selected products with their negative health effects to help you better counsel and guide your patients and their families. 2 TOBACCO: Smokeless Tobacco THE FACTS • Smokeless tobacco is not burned or smoked but always contains nicotine.* V It includes tobacco that can be sucked, chewed, spit or swallowed, depending on the product. PRODUCT NAME WHAT IT IS Chewing • Comes in loose leaf, plug or twist form Tobacco V Used by taking a piece and placing it between the cheek and gums; Also Known As may require spitting. Chew Snuff • Comes in moist, dry or packet (snus) form Also Known As V Moist snuff is used by taking a pinch and placing it between the lip Dip or cheek and gums; requires spitting. V Dry snuff is used by putting a pinch of powder in the mouth or by sniffing into the nose. -

Philosophy, Rhetoric, and Argument 1

Philosophy, Rhetoric, and Argument 1 LEARNING OUTCOMES t’s often said that everyone philosophy: has a philosophy. It’s the intellectual Upon carefully studying this chapter, students also often said that activity of discerning should better comprehend and be able to explain: I and removing philosophical musings are contradictions ●● The ways in which philosophy, following the merely matters of opinion. among nonempirical, example of Socrates, can be distinguished from But in very important ways, reasoned beliefs mere rhetoric and sophistry, and the value of both of these assertions that have universal philosophical exploration. misrepresent philosophy. importance, with the First, philosophy isn’t so resulting benefit of ●● A working definition of philosophy, including its much something you have; achieving a greater primary sub‐areas of philosophical exploration understanding of rather, it is something that (especially metaphysics, epistemology, and the world and one’s you do. It is a process or ethics). place within it. activity, and a carefully ●● Different kinds of arguments to employ and crafted one at that. Second, fallacies to avoid in (philosophical) reasoning. when taking care to do philosophy well, it is unfair to say that philosophical judgments are merely ●● The debate about whether philosophical matters of personal opinion. This chapter strives to analysis can establish objectively true reinforce these refined estimations of philosophy. statements, and some arguments relevant to The chapters that follow will further reinforce them. this debate. By the time you reach the end of the text, and with ●● How Thank You for Smoking, Minority Report, the help of some very notable philosophers from and The Emperor’s ClubCOPYRIGHTED can be employed to the MATERIAL history of philosophy, you should have a much better understand and appreciate philosophy better grasp of what philosophy is and how it is and the philosophical process.