Ciiinm™™ a National Park Service Technical Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essays of an Information Scientist, Vol:5, P.703,1981-82 Current

3. -------------0. So you wanted more review articles- ISI’s new Index to Scientific Reviews (ZSR) will help you find them. Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1977. Vol. 2. p. 170-l. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (44):5-6, 30 October 1974.) 4. --------------. Why don’t we have science reviews? Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1977. Vol. 2. p. 175-6. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (46):5-6, 13 November 1974.) 5. --1.1..I- Proposal for a new profession: scientific reviewer. Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1980. Vol. 3. p. 84-7. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (14):5-8, 4 April 1977.) Benjamin Franklin- 6. ..I. -.I-- . ..- The NAS James Murray Luck Award for Excellence in Scientific Reviewing: G. Alan Robison receives the first award for his work on cyclic AMP. Essays of an information Philadelphia’s Scientist Extraordinaire scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1981. Vol. 4. p. 127-31. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (18):5-g, 30 April 1979.) 7, .I.-.- . --.- The 1980 NAS James Murray Luck Award for Excellence in Scientific Reviewing: Conyers Herring receives second award for his work in solid-state physics. Number 40 October 4, 1982 Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1981. Vol. 4. p. 512-4. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (25):5-7, 23 June 1980.) Earlier this year I invited Current Con- ness. Two years later, he was appren- 8. ..- . - . ..- The 1981 NAS James Murray Luck Award for Excellence in Scientific Reviewing: tents@ (CC@) readers to visit Philadel- ticed to his brother James, a printer. -

Ben Franklin Walking Tour

CONTACT: Cara Schneider, GPTMC (215) 599-0789, [email protected] Sharon Murphy, Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary (215) 790-7867, [email protected] WALKING IN FRANKLIN’S FOOTSTEPS th Tour Created For Franklin’s 300 Birthday Features Modern And Historic Sites In Old City PHILADELPHIA, April 25, 2005 – Benjamin Franklin may have left big shoes to fill, but walking in his footsteps is easy in Philadelphia, thanks to a new self-guided tour developed for the Founding Father’s 300th birthday in 2006. The one-hour walking tour, available online at www.gophila.com/itineraries, takes visitors to city landmarks that were significant in Franklin’s time as well as to innovative new attractions that bring to life the forward thinker’s insights. LOCATION: Old City, Society Hill TRANSPORTATION: Feet TIME: Walking the tour route will take approximately one hour but can take longer if you actually visit each site. SUMMARY: A one-hour walking tour of key Benjamin Franklin-related sites in Philadelphia’s Historic District HIGHLIGHTS: National Constitution Center, Christ Church Burial Ground, Franklin Court, Second Bank of the United States and Independence Hall FEES: All attractions are free unless otherwise noted. ITINERARY: Begin at the Independence Visitor Center, where the film Independence traces Ben Franklin’s role in the nation’s earliest days. While you’re there, gather brochures about Philadelphia’s many other attractions, and pick up your free, timed tickets for Independence Hall. When you leave the Independence Visitor Center, make a right onto 6th Street and head to the th Federal Reserve Bank, located on 6 Street between Market and Arch Streets: • Federal Reserve Bank – During his career as a printer, Franklin printed currency for several colonies, including Pennsylvania and New Jersey. -

Ben Franklin Parkway and Independence Mall Patch Programs

Ben Franklin Parkway and Independence Mall Patch Programs 1 Independence Mall Patch Program Introduction – Philadelphia’s History William Penn, a wealthy Quaker from London earned most of his income from land he owned in England and Ireland. He rented the land for use as farmland even though he could have made much more money renting it for commercial purposes. He considered the rent he collected from the farms to be less corrupt than commercial wealth. He wanted to build such a city made up of farmland in Pennsylvania. As soon as William Penn received charter for Pennsylvania, Penn began to work on his dream by advertising that he would establish, “ A large Towne or City” on the Delaware River. Remembering the bubonic plague in London (1665) and the disastrous fire of 1666, Penn wanted, “ A Greene county Towne, which would never be burnt, and always be wholesome.” In 1681, William Penn announced he would layout a “Large Towne or City in the most convenient place upon the river for health and navigation.” Penn set aside 10,000 acres of land for the Greene townie on the Delaware and he stretched the town to reach the Schuylkill so that the city would face both rivers. He acquired one mile of river frontage on the Schuylkill parallel to those on the Delaware. Thus Philadelphia became a rectangle 1200 acres, stretching 2 miles in the length from east to west between the 3 rivers and 1 mile in the width North and South. William Penn hoped to create a peaceful city. When he arrived in 1682, he made a Great Treaty of Friendship with the Lenni Lenape Indians on the Delaware. -

George Washington Was Perhaps in a More Petulant Mood Than

“A Genuine RepublicAn”: benjAmin FRAnklin bAche’s RemARks (1797), the FedeRAlists, And RepublicAn civic humAnism Arthur Scherr eorge Washington was perhaps in a more petulant mood than Gusual when he wrote of Benjamin Franklin Bache, Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, in 1797: “This man has celebrity in a certain way, for his calumnies are to be exceeded only by his impudence, and both stand unrivalled.” The ordinarily reserved ex-president had similarly commented four years earlier that the “publica- tions” in Philip Freneau’s National Gazette and Bache’s daily newspaper, the Philadelphia General Advertiser, founded in 1790, which added the noun Aurora to its title on November 8, 1794, were “outrages on common decency.” The new nation’s second First Lady, Abigail Adams, was hardly friendlier, denounc- ing Bache’s newspaper columns as a “specimen of Gall.” Her husband, President John Adams, likewise considered Bache’s anti-Federalist diatribes and abuse of Washington “diabolical.” Both seemed to have forgotten the bygone, cordial days in Paris during the American Revolution, when their son John Quincy, two years Bache’s senior, attended the Le Coeur boarding school pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 80, no. 2, 2013. Copyright © 2013 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.153.205 on Mon, 15 Apr 2019 13:25:50 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms pennsylvania history with “Benny” (family members also called him “Little Kingbird”). But the ordinarily dour John Quincy remembered. Offended that the Aurora had denounced his father’s choosing him U.S. -

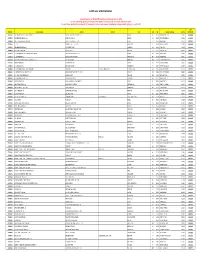

Certificates of Authorization

Certificates of Authorization Included below are all WV ACTIVE COAs licensed through June 30, 2015. As of the date of this posting, all Company COA updates received prior to February 11, 2015 are included. The next Roster posting will be in May 2015, immediately prior to renewal season, updating those in good standing through June 30, 2015. COA WV COA # Company Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Zip Engineer‐In‐Charge WV PE # EXPIRATION C04616‐00 2301 STUDIO, PLLC D.B.A. BLOC DESIGN, PLLC 1310 SOUTH TRYON STREET SUITE 111 CHARLOTTE NC 28203 WILLIAM LOCKHART 017282 6/30/2015 C04740‐00 3B CONSULTING SERVICES, LLC 140 HILLTOP AVENUE LEBANON VA 24266 PRESTON BREEDING 018263 6/30/2015 C04430‐00 3RD GENERATION ENGINEERING, INC. 7920 BELT LINE ROAD SUITE 591 DALLAS TX 75254 MARK FISHER 019434 6/30/2015 C02651‐00 4SE, INC. 7 RADCLIFFE STREET SUITE 301 CHARLESTON SC 29403 GEORGE BURBAGE 015290 6/30/2015 C04188‐00 4TH DIMENSION DESIGN, INC. 817 VENTURE COURT WAUKESHA WI 53189 JOHN GROH 019415 6/30/2015 C02308‐00 A & A CONSULTANTS, INC. 707 EAST STREET PITTSBURGH PA 15212 JACK ROSEMAN 007481 6/30/2015 C02125‐00 A & A ENGINEERING, CIVIL & STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS 5911 RENAISSANCE PLACE SUITE B TOLEDO OH 43623 OMAR YASEIN 013981 6/30/2015 C01299‐00 A 1 ENGINEERING, INC. 5314 OLD SAINT MARYS PIKE PARKERSBURG WV 26104 ROBERT REED 006810 6/30/2015 C03979‐00 A SQUARED PLUS ENGINEERING SUPPORT GROUP, LLC 3477 SHILOH ROAD HAMPSTEAD MD 21074 SHERRY ABBOTT‐ADKINS 018982 6/30/2015 C02552‐00 A&M ENGINEERING, LLC 3402 ASHWOOD LANE SACHSE TX 75048 AMMAR QASHSHU 016761 6/30/2015 C01701‐00 A. -

Download File

A PRESERVATION REVOLUTION: RESURRECTING FRANKLIN COURT FOR THE BICENTENNIAL Ryan Zeek Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Historic Preservation Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation Columbia University May 2019 Acknowledgments I am greatly indebted to my advisor, Andrew Dolkart, for his guidance and feedback throughout this process. Likewise, I am similarly thankful for the input provided by my readers, Paul Bentel and Will Cook. I received inspiration and support from other faculty members as well, including Michael Adlerstein, Erica Avrami, Françoise Bollack, Chris Neville, Richard Pieper, and Norman Weiss – thank you. I am also very thankful for the support that I received from Tyler Love and Andrea Ashby at the National Park Service’s Independence National Historical Park Archives, as well as from Heather Isbell Schumacher at the University of Pennsylvania’s Architectural Archives. I would also like to thank Franklin Vagnone and Jeffrey Cohen, who kindly lent their time to answer my questions and point me in valuable directions. In addition, I would like to thank Glen Umberger, for it was during a conversation with him while I was an intern at The New York Landmarks Conservancy that the idea for this thesis first entered the world. I am also indebted to the Preservation League of New York State and the Zabar Family Scholarship for their support. Without the members of my cohort, who listened to my ideas and struggles both, and buoyed me up throughout the whole process, this thesis would not have been possible – thank you all for being some of the most incredible colleagues that a preservationist could ever want. -

Additional Resources on Franklin.Pdf

53 Web Resources for teachers and students Benjamin Franklin http://www.pbs.org/benjaminfranklin/ Benjamin Franklin: Glimpses of the Man http://sln.fi.edu/franklin/rotten.html Ben’s Guide http://bensguide.gpo.gov/benfranklin/ Benjamin Franklin In His Own Words http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/franklin-home.html Franklin Court http://www.nps.gov/inde/planyourvisit/franklin-court.htm Resources for Teachers (Print) Block, Syemour Stanton. Benjamin Franklin, genius of Kites, flights and voting rights. McFarland & Co., 2004. Franklin, Benjamin. Franklin Writtings. The Library of America, 1987. Franklin, Benjamin and Paul M. Zall. Franklin on Franklin. University Press of Kentucky, 2000. Isaacson, Walther. Benjamin Franklin an American Life. Simon & Schuster, 2003. Lemay, J.A. The life of Benjamin Franklin. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. Talbott, Page. Benjamin Franklin in Search of a Better World. Yale University Press, 2005. Waldstreicher, David. Runaway America. Hill and Wang, 2004. Resources for Students (Print) Adler, David A. A Picture Book of Benjamin Franklin. Holiday House, 1990. A biography of Franklin geared toward primary children. Adler, David A. B. Franklin Printer. Holiday House, 2001. A detailed biography for older students; contains a detailed time line of events in Franklin’s life. Barretta, Gene. Now & Ben: The Modern Inventions of Benjamin Franklin. Henry Holt and Company, 2006. A picture book that compares modern inventions with those designed by Franklin. Cousins, Margaret. Ben Franklin of Old Philadelphia. Landmark Books, Random House, 1952. A biography written for middle graders that is part of an acclaimed series of children’s history books. Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia 54 Dash, Joan. -

The House Most Widely Associated with Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) Is the One That He Built for His Family in Philadelphia, I

The House that Franklin Built by Page Talbott he house most widely associated with Benjamin Franklin a house of his own, having previously resided with his family in smaller (1706–1790) is the one that he built for his family in rented dwellings in the neighborhood. T Philadelphia, in a quiet, spacious courtyard off Market Street Like Jefferson at Monticello, Franklin had a hand in the design of between Third and Fourth Streets. Newly returned from his seven-year the house, though he spent the actual building period as colonial stay in London in late 1762, Benjamin Franklin decided it was time for agent in England. His wife, Deborah (1708–1774), oversaw the con- struction, while Franklin sent back Continental goods and a steady stream of advice and queries. Although occupied with matters of busi- ness, civic improvement, scientific inquiry, and affairs of state, he was never too busy to advise his wife and daughter about fashion, interior decoration, and household pur- chases. Franklin’s letters to his wife about the new house — and her responses — offer extraordinary detail about its construction and embellishment. The house was razed in 1812 to make room for a street and several smaller houses, but these letters, together with Gunning Bedford’s 1766 fire insurance survey, help us visualize this elegant mansion, complete with wainscoting, columns and pilasters, pediments, dentil work, frets and cornices.1 On his return to Philadelphia in November 1762, Franklin and his wife had the opportunity to plan and start building their first house, only a few steps from where they had first laid eyes on each other. -

Old Philadelphia: Redevelopment and Conservation Author(S): William E

Old Philadelphia: Redevelopment and Conservation Author(s): William E. Lingelbach Source: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 93, No. 2, Studies of Historical Documents in the Library of the American Philosophical Society (May 16, 1949), pp. 179-207 Published by: American Philosophical Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3143438 Accessed: 30-08-2018 19:04 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Philosophical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society This content downloaded from 65.213.241.226 on Thu, 30 Aug 2018 19:04:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms OLD PHILADELPHIA: REDEVELOPMENT AND CONSERVATION WILLIAM E. LINGELBACH Librarian, American Philosophical Society; Professor Emeritus of Modern European History, University of Pennsylvania FEDERAL STATE AND CITY PLANS a National Shrine in accordance with the terms THE extraordinary awakening of ofcivic a contract interest between the city and the Department in Old Philadelphia in the last decade of the seems Interior. -

WV Registered Professional Engineers

WV Registered Professional Engineers Included below are all WV ACTIVE PEs licensed through June 30, 2015. As of the date of this posting, all PE updates received prior to February 11, 2015 are included. The next Roster posting will be in May 2015, immediately prior to renewal season, updating those in good standing through June 30, 2015. PE WV PE# Last Name First Name Middle Suffix Company Affiliation Address 1 Address 2 City State Zip EXPIRATION 010956 ABBATE MARTIN A URS CONSULTANTS, INC. 4060 FOREST RUN CIRCLE MEDINA OH 44256 6/30/2015 014683 ABBATTISTA STEVEN O'DEA, LYNCH, ABBATTISTA CONSULTING ENGINEERS, PC 50 BROADWAY HAWTHORNE NY 10532 6/30/2015 017932 ABBEY DAVID S DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT GROUP, LLC 4209 GALLATIN PIKE NASHVILLE TN 37216 6/30/2015 012945 ABBOTT DOUGLAS A HYMAN & ROBEY 203 AMY DRIVE CAMDEN NC 27921 6/30/2015 019562 ABBOTT KEVIN C UOP RUSSELL LLC 4216 N SPRUCE AVENUE BROKEN ARROW OK 74012 6/30/2015 018064 ABBOTT MICHAEL C ABBOTT ELECTRIC, INC. 1935 ALLEN AVENUE SOUTHEAST CANTON OH 44707 6/30/2015 015110 ABBOTT PAUL E JR KIBART, INC. 901 DULANEY VALLEY ROAD SUITE 301 TOWSON MD 21204 6/30/2015 018982 ABBOTT‐ADKINS SHERRY A A SQUARED PLUS ENGINEERING SUPPORT GROUP, LLC 3477 SHILOH ROAD HAMPSTEAD MD 21074 6/30/2015 019477 ABDELAHAD FIRAS BUNTING GRAPHICS, INC. 1346 MEADOWBROOK DRIVE CANONSBURG PA 15317 6/30/2015 017628 ABDELFATTAH OSSAMA MEP DESIGNS INC. 8721 PLANTATION LANE # 301 MANASSAS VA 20110 6/30/2015 015288 ABED KHALID J CHA CONSULTING, INC. 4019 WELBY DRIVE MIDLOTHIAN VA 23113 6/30/2015 019145 ABEL DENNIS D FDH ENGINEERING, INC. -

Franklin Court

VSBA FRANKLIN COURT Architects: Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc. Location: Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia, PA Client: United States National Park Service Area: 30,000 sf Construction Cost: $4,750,000 Completion: 1976 This museum and memorial to Benjamin Franklin rests on the site of the home Franklin built for himself, set back from Market Street in Philadelphia’s historic Old City. The challenge was to design a contextually appropriate but distinctive structure: imaginatively serving educational and memorial purposes, conveying the site and builder’s rich history, and reflecting Franklin’s spirit and accomplishments. Our response departed from the usual museum and memorial architecture by placing the main exhibit area underground and designing a steel “ghost” structure representing the original house. This preserved the site of Franklin’s garden as open space. Viewing ports in situ allow visitors to see the few archaeological remains of the house unearthed during earlier research. Quotes from Franklin’s letters to his wife during the house’s construction are engraved in the paving. Five historic houses that once faced Market Street were reconstructed. Two are archaeological exhibits and the others house administrative offices and a shop. As in Franklin’s time, they enclose the garden beyond. The entry to the memorial through a passageway under these houses offers a sense of discovery and drama, of both physical and temporal movement. The inner court’s landscaping recalls an 18th century garden while providing comfortable yet sturdy visitor accommodations. Franklin Court is now one of the most visited attractions in Independence Park. It’s also used by nearby residents and workers from surrounding office buildings during lunchtimes. -

Independence NHP: Franklin's House-Historic Structures Report

INDEPENDENCE Franklin's House Historic Stuctures Report FRANKLIN'S HOUSE Historic Structures Report Historical Data Section Independence N. H. P. Pennsylvania By John Platt November 29, 1969 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Dvision of History Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS inde/hsr1/index.htm Last Updated: 30- Jun- 2008 INDEPENDENCE Franklin's House Historic Stuctures Report TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER PREFACE LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1. TWO HOMECOMINGS IN THE LIFE OF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN 2. DR. FRANKLIN BUILDS 3. SORTING OUT THE ROOMS 4. LATER HISTORY OF THE HOUSE ENDNOTES APPEND1X A APPENDIX B APPENDIX C SOURCES ILLUSTRATIONS Title Page Photograph: Taken from a portrait of Franklin painted from life by David Martin in 1766, just about the time the house was finished. This is the way Franklin would have appeared at home while absorbed in matters of importance. A visitor in 1781 did indeed find him "in the exact posture in which he is represented by an admirable engraving from his portrait; his left arm resting upon the table, his chin supported by the thumb of his right hand." LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS No. 1. JOHN READ PLAN OF FRANKLIN COURT, 1765. No. 2. PORTRAIT OF DEBORAH FRANKLIN. No. 3. "IRON RAIL FROM CHIMNEY TO CHIMNEY." No. 4. DINING ROOM, BENJAMIN FRANKLIN HOUSE, 1763-66. NO. 5. WILLIAM LOGAN'S HOUSE ON SECOND STREET. No. 6. DETAIL FROM KRIMMEL ENGRAVING "ELECTION 1815," OF INDEPENDENCE HALL CLOCK CASE. No. 7. ICE HOUSE. No. 8. SECOND FLOOR PLAN OF HOUSE. No. 9. FIRST FLOOR PLAN OF HOUSE.