Causes and Forms of Marginalization: an Investigation of Social Marginalization of Craft Workers in Dembecha Woreda, North Western Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Lupinus Albus L.) Landraces

AJCS 11(1):55-62 (2017) ISSN:1835-2707 doi: 10.21475/ajcs.2017.11.01.pne226 Genotype by trait biplot analysis to study associations and profiles of Ethiopian white lupin (Lupinus albus L.) landraces Mulugeta Atnaf*, Kassahun Tesfaye, Kifle Dagne and Dagne Wegary Supplementary Table 1: Ethiopian white lupin landraces considered for the study. (a). Ethiopian white lupin landraces considered for the first study EBI EBI Acc no code Zone District Altitude Acc no code Zone District Altitude Acc1 242279 Awi Ankesha 2310 Acc37 238993 BD Sp Bahir dar 1990 Acc2 242280 Awi Ankesha 2185 Acc38 238994 BD Sp Bahir dar 2020 Acc3 242281 Awi Ankesha 2310 Acc39 239011 BD Sp Bahir dar 2090 Acc4 242282 Awi Ankesha 2410 Acc40 239020 BD Sp Bahir dar 1940 Acc5 242266 WG Dembecha 2110 Acc41 239022 BD Sp Bahir dar 1930 Acc6 239044 Awi Banja 2600 Acc42 239023 BD Sp Bahir dar 1930 Acc7 242277 Awi Banja 2560 Acc43 228519 SG Dera Acc8 242278 Awi Banja 2560 Acc44 242311 SG Dera 1860 Acc9 242283 Awi Banja 2160 Acc45 242312 SG Dera 1960 Acc10 242284 Awi Banja 1960 Acc46 242313 SG Dera 1960 Acc11 236619 Awi Banja 2570 Acc47 242314 SG Dera 2160 Acc12 239045 Awi Banja 2600 Acc48 242315 SG Dera 2380 Acc13 242273 Awi Banja 2490 Acc49 242316 SG Dera 2460 Acc14 242274 Awi Banja 2450 Acc50 242268 WG Dembecha 2010 Acc15 242276 Awi Banja 2590 Acc51 239018 WG BD Z 1950 Acc16 105018 Acc52 242319 SG Dera 2510 Acc17 105005 Awi Dangila 1940 Acc53 105002 SG Este 2420 Acc18 228520 Awi Dangila Acc54 226034 SG Este 2560 Acc19 242290 Awi Dangila 2240 Acc55 242321 SG Este 2630 Acc20 242291 -

The Ethiopian Journal of Social Sciences Volume 7, Number 1, May 2021

The Ethiopian Journal of Social Sciences Volume 7, Number 1, May 2021 The 2016 Mass Protests and the Responses of Security Forces in ANRS, Ethiopia: Awi and West Gojjam Zones in Focus 1Kidanu Atinafu Abstract This study examined security forces’ abuse of power and their accountability in connection with the 2016 mass protests that unfolded in the Amhara National Regional State (ANRS) in general and Awi and West Gojjam Zones in particular. Specifically, the study assessed the nature of the use of force and the consequent investigations to punish security forces who abused their power. To address these objectives, the study employed a mixed methods research approach with a concurrent parallel design. Data for this research was obtained both from primary and secondary data sources. Interview, questionnaire and document analysis were used to collect data. A sample of 384 respondents was selected randomly to complete the questionnaire, whereas key informants were selected for the interview through snowball sampling technique. Based on the data gathered from all these sources, the study revealed that security forces committed arbitrary and extrajudicial killings and inflicted injuries against protesters who were chiefly unarmed and non-violent. The measures taken were found excessive and arbitrary with several civilians risking their lives and physical wellbeing. With few exceptions, the administrations at different levels of the government failed to investigate these extrajudicial and arbitrary killings and injuries inflicted in the process of punishing alleged perpetrators of the protest using civil and criminal laws. It is finally recommended to undertake independent investigations into the legitimacy of the murders, injuries, beatings and other forms of violence committed by the security forces. -

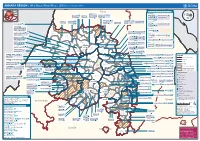

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Determinants of Maize Market Supply, Production and Marketing Constraints: the Case of Dembecha District, West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

International Journal of Economy, Energy and Environment 2020; 5(5): 83-89 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijeee doi: 10.11648/j.ijeee.20200505.13 ISSN: 2575-5013 (Print); ISSN: 2575-5021 (Online) Determinants of Maize Market Supply, Production and Marketing Constraints: The Case of Dembecha District, West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia Desalegn Wondim 1, *, Tewodros Tefera 2, Yitna Tesfaye 2 1Department of Agribusiness and Value Chain Management, Burie Campus, Debre Markos University, Burie, Ethiopia 2School of Environment, Gender and Development Studies, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia Email address: *Corresponding author To cite this article: Desalegn Wondim, Tewodros Tefera, Yitna Tesfaye. Determinants of Maize Market Supply, Production and Marketing Constraints: The Case of Dembecha District, West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Economy, Energy and Environment . Vol. 5, No. 5, 2020, pp. 83-89. doi: 10.11648/j.ijeee.20200505.13 Received : July 22, 2020; Accepted : August 31, 2020; Published : October 7, 2020 Abstract: West Gojjam is one of the maize belt zones in Ethiopia, and Dembecha district is among the potential districts in West Gojjam zone. However, despite its maize production potential of the district, marketed supply determinants, maize production and marketing constraints hampered producer’s decision and engagement on maize production and marketing. Thus, this study was attempts to address the determinants of marketed supply of maize, constraints and opportunities in Dembecha district in the year 2018. Data were collected from primary and secondary sources using appropriate tools. Primary data were collected from randomly selected 155 maize producers, 20 consumers as well as 40 maize grain traders, 10 alcohol processors using semi-structured questionnaire. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

Narratives of Environmental Disaster in Ethiopia: the Political Ecology of Famine

Narratives of Environmental Disaster in Ethiopia: The Political Ecology of Famine By Abeal Biruk Supervised by Dr. Nirupama Agrawal A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario Canada July 31st, 2020 Abstract: The conception and inheritance of narratives are an important component of being human. At the foundation of many societies, narratives take shape through verbal and written stories, songs, artifacts, records of events, testimonials, and even memories. These narratives are carried forward to the next generation in the hopes of remembering and educating those who look to the past to understand their present and future environments. Despite ethnic and cultural differences, groups of people find ways to preserve the narratives that can either form or unite their identities together. This statement by no means disparages the impact of historical forces, such as European colonialism, that has tampered the narratives of countless Indigenous groups in North America, the Global South and Africa. The pursuit of identifying narratives can aid in the unravelling of so-called truths of history, seeking justice for people who can no longer do so themselves, and healing generations of systematic oppression in countless broken communities. Ethiopia has spent over a century facing significant drought conditions that have rendered many of the nation’s northern regions vulnerable to famine. For this reason, this paper focuses on the impacts of anthropogenic environmental disasters in Ethiopia, specifically the famine of 1983- 1985. The goal of this research is to analyze the 1983-1985 famine to understand its significance in relation to contemporary Ethiopian disaster management. -

AMHARA Demography and Health

1 AMHARA Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 2021 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org 2 Amhara Suggested citation: Amhara: Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 20201 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org Landforms, Climate and Economy Located in northwestern Ethiopia the Amhara Region between 9°20' and 14°20' North latitude and 36° 20' and 40° 20' East longitude the Amhara Region has an estimated land area of about 170000 square kilometers . The region borders Tigray in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumiz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan to the west [1]. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 140 Weredas (see map at the bottom of this page). There are about 3429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units) [1]. "Decision-making power has recently been decentralized to Weredas and thus the Weredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas." The 11 administrative zones are: North Gonder, South Gonder, West Gojjam, East Gojjam, Awie, Wag Hemra, North Wollo, South Wollo, Oromia, North Shewa and Bahir Dar City special zone. [1] The historic Amhara Region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, and millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. In this Region are located, the world- renowned Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder, and Lalibela. "Interspersed on the landscape are higher mountain ranges and cratered cones, the highest of which, at 4,620 meters, is Ras Dashen Terara northeast of Gonder. -

Based Natural Resource Management in Wodebeyes

Action Oriented Training of Natural Resource Management Case Study of Community- Based Natural Resource Management in Wodebeyesus Village, Debaitilatgin Woreda, Ethiopia Research Report submitted to Larenstein University of Applied Sciences In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Development, specialization Training in Rural Extension and Transformation (TREAT) BY Habtamu Sahilu Kassa September 2008 Wageningen the Netherlands © Copyright Habtamu Sahilu Kassa, 2008. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this research project in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a post graduate degree, I agree that the library of the university may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this research project in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purpose may be granted by Larenstein Director of Research. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this research project or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and the University in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my research project. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this research project in whole or part should be addressed to: Director of Research Larenstein University of Professional Education P.O.Box9001 6880GB Velp The Netherlands Fax: 31 26 3615287 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My sincere thanks is to the Amahara National Regional State and the Sida support program, who offered me to study my masters in development program in the Netherlands. -

Woreda-Level Crop Production Rankings in Ethiopia: a Pooled Data Approach

Woreda-Level Crop Production Rankings in Ethiopia: A Pooled Data Approach 31 January 2015 James Warner Tim Stehulak Leulsegged Kasa International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) was established in 1975. IFPRI is one of 15 agricultural research centers that receive principal funding from governments, private foundations, and international and regional organizations, most of which are members of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). RESEARCH FOR ETHIOPIA’S AGRICULTURE POLICY (REAP): ANALYTICAL SUPPORT FOR THE AGRICULTURAL TRANSFORMATION AGENCY (ATA) IFPRI gratefully acknowledges the generous financial support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) for IFPRI REAP, a five-year project to support the Ethiopian ATA. The ATA is an innovative quasi-governmental agency with the mandate to test and evaluate various technological and institutional interventions to raise agricultural productivity, enhance market efficiency, and improve food security. REAP will support the ATA by providing research-based analysis, tracking progress, supporting strategic decision making, and documenting best practices as a global public good. DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared as an output for REAP and has not been reviewed by IFPRI’s Publication Review Committee. Any views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of IFPRI, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. AUTHORS James Warner, International Food Policy Research Institute Research Coordinator, Markets, Trade and Institutions Division, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [email protected] Timothy Stehulak, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Research Analyst, P.O. -

The Impact of Podoconiosis on Quality of Life in Northern Ethiopia

The impact of podoconiosis on quality of life in Northern Ethiopia Article (Published Version) Mousley, Elizabeth, Deribe, Kebede, Tamiru, Abreham and Davey, Gail (2013) The impact of podoconiosis on quality of life in Northern Ethiopia. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11. p. 122. ISSN 1477-7525 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/48181/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Mousley et al. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2013, 11:122 http://www.hqlo.com/content/11/1/122 RESEARCH Open Access The impact of podoconiosis on quality of life in Northern Ethiopia Elizabeth Mousley1, Kebede Deribe1,2*, Abreham Tamiru3 and Gail Davey1 Abstract Background: Podoconiosis is one of the most neglected tropical diseases, which untreated, causes considerable physical disability and stigma for affected individuals. -

Documentation of Traditional Knowledge Associated with Medicinal Animals in West Gojjam Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia

Documentation of Traditional Knowledge Associated with Medicinal Animals in West Gojjam Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia Manaye Misganaw Motbaynor ( [email protected] ) Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4313-8336 Nigussie Seboka Tadesse Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute Abiyselassie Mulatu Gashaw Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute Ashena Ayenew Hailu Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute Research Keywords: Informant consensus, Medicinal Animals, Traditional Knowledge, Use values Posted Date: June 19th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-31098/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/17 Abstract Background In Ethiopia, Ethnozoology and Zootherapeutic research is very limited and little attention has been given.The study was designed to investigate and document traditional knowledge associated with medicinal animals in West Gojjam Zone of Javitenan, North Achefer, and Bahir Dar Zuria districts. Methods Ethnozoological data were collected using structured questionnaires and use value (UV), informant consensus factor (ICF), delity level (FL), preferential ranking, and paired comparison were analyzed. Results A total of 26 animal species and were identied and recorded as a source medicine to treat 33 types of ailments. Animal derived medicines of Bos indicus , Trigona spp . and Apis mellifera were frequently reported species to treat various ailments. Bos indicus , Trigona spp ., Apis mellifera , Hyaenidae carnivora , and Labeobarbus spp . were the most frequent use value reports (84%, 52%, 43%, 37% and 36%) respectively. Informants reported 25 animal parts to treat ailments. Honey and meat took the highest frequency use report followed by puried butter, Milk, Liver, fatty meat and Cheese stored more than 7 year were described with average ICF value of 69%. -

Uptake of Minimum Acceptable Diet Among Children Aged 6–23 Months in Orthodox Religion Followers During Fasting Season in Rura

Mulat et al. BMC Nutrition (2019) 5:18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-019-0274-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Uptake of minimum acceptable diet among children aged 6–23 months in orthodox religion followers during fasting season in rural area, DEMBECHA, north West Ethiopia Efram Mulat1, Girma Alem2, Wubetu Woyraw3* and Habtamu Temesgen1 Abstract Background: Under-nutrition is the cause for poor physical and mental development and has more burden among infants and young children aged between 6 and 23 months. Cultural practices like not providing animal source foods for infants and young child aged between 6 and 23 months were barrier for practicing proper children feeding. The aim of this study was to assess minimum acceptable diet and associated factors among children aged between 6 and 23 months in Orthodox religion during fasting season in rural area, Dembecha, Ethiopia. Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted to assess Minimum Acceptable diet. Random sampling technique was applied to select 506 study participants. Interview was used to collect data on Practice of minimum acceptable diet, minimum dietary diversity, minimum meal frequency and related factors among children aged between 6 and 23 months from mothers / caregivers. Result: About 8.6% of infants and young children aged between 6 and 23 months received minimum acceptable diet. Education status of mother(AOR = 0.22,95%CI:0.1, 0.48), involvement of mother in decision making (AOR = 0.22,95%CI:0. 10,0.48), birth order of index children (AOR = 0.36,95%CI:0.14,0. 94), knowledge on feeding frequency (AOR = 0.3,95% CI:0.