F:\Assault Weapons\On Target Brady Rebuttal\AW Final Text for PDF.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thompson Brochure 9Th Edition.Indd

9th Edition Own A Piece Of American History Thompson Submachine Gun General John T. Thompson, a graduate of West Point, began his research in 1915 for an automatic weapon to supply the American military. World War I was dragging on and casualties were mounting. Having served in the U.S. Army’s ordnance supplies and logistics, General Thompson understood that greater fi repower was needed to end the war. Thompson was driven to create a lightweight, fully automatic fi rearm that would be effective against the contemporary machine gun. His idea was “a one-man, hand held machine gun. A trench broom!” The fi rst shipment of Thompson prototypes arrived on the dock in New York for shipment to Europe on November 11, 1918 the day that the War ended. In 1919, Thompson directed Auto-Ordnance to modify the gun for nonmilitary use. The gun, classifi ed a “submachine gun” to denote a small, hand-held, fully automatic fi rearm chambered for pistol ammunition, was offi cially named the “Thompson submachine gun” to honor the man most responsible for its creation. With military and police sales low, Auto-Ordnance sold its submachine guns through every legal outlet it could. A Thompson submachine gun could be purchased either by mail order, or from the local hardware or sporting goods store. Trusted Companion for Troops It was, also, in the mid ‘20s that the Thompson submachine gun was adopted for service by an Dillinger’s Choice offi cial military branch of the government. The U.S. Coast Guard issued Thompsons to patrol While Auto-Ordnance was selling the Thompson submachine gun in the open market in the ‘20s, boats along the eastern seaboard. -

Gun Industry Trade Association Resorts to Deceit After Cbs News 60 Minutes Documents Danger of Fifty Caliber Anti-Armor Rifles

GUN INDUSTRY TRADE ASSOCIATION RESORTS TO DECEIT AFTER CBS NEWS 60 MINUTES DOCUMENTS DANGER OF FIFTY CALIBER ANTI-ARMOR RIFLES National Shooting Sports Foundation Seeks to Fend Off Oversight Of Ideal Terror Tool By Lying About Federal Records of Firearms Sales Stung by a CBS News 60 Minutes documentary that reported the looming danger of terrorist use of powerful 50 caliber anti-armor sniper rifles that are freely sold to civilians, the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), a gun industry trade association, has posted an egregiously dishonest misrepresentation regarding the lack of federal records kept on the sale of such firearms. The 60 Minutes report on January 9, 2005, accurately reported that no one in the federal government—much less the federal anti-terrorism establishment—knows who has these powerful long range anti-materiel sniping rifles.1 The 50 caliber anti- armor rifle can blast through armor, set bulk fuel stores on fire, breach chemical storage tanks, shoot down helicopters in flight, and destroy fully-loaded jet airliners on the ground—all from more than a mile away. The NSSF, desperate to fend off a growing state-led grassroots movement to regulate these weapons of war in the wake of indifference by the Bush administration and inaction by the majority leadership of the U.S. Congress, has taken out of context four words spoken by Violence Policy Center (VPC) Senior Policy Analyst Tom Diaz, and attempted by innuendo, half-truth, and outright lie to twist them into a “boldly false assertion.” This desperate smear withers under close examination. In the passage NSSF seeks to distort, 60 Minutes first correctly notes that the VPC’s objective, as articulated by Diaz, is to bring the anti-armor rifles under the existing federal National Firearms Act, under which similar weapons of war—such as machine guns, rockets, and grenades—are individually registered and all transfers recorded by the federal government. -

Independent Women's Law Center

No. 20-843 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- NEW YORK STATE RIFLE & PISTOL ASSOCIATION INC., ET AL., Petitioners, v. KEVIN P. B RUEN, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SUPERINTENDENT OF NEW YORK STATE POLICE, ET AL., Respondents. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Second Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF FOR THE INDEPENDENT WOMEN’S LAW CENTER AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARC H. ELLINGER JOHN M. REEVES STEPHANIE S. BELL Counsel of Record ELLINGER & ASSOCIATES, LLC REEVES LAW LLC 308 East High Street, 7733 Forsyth Blvd., Suite 300 Ste. 1100-1192 Jefferson City, MO 65101 St. Louis, MO 63105 Telephone: (573) 750-4100 Telephone: (314) 775-6985 Email: mellinger@ Email: reeves@ ellingerlaw.com reeveslawstl.com Email: sbell@ ellingerlaw.com Counsel for Amicus Curiae July 20, 2021 ================================================================================================================ i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................. i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................... ii INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ......................... 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT -

Stacey Pierce-Talsma DO, MS Medl, FNAOME Health Policy Fellowship 2014-2015

Gun Violence: A Case for Supporting Research Stacey Pierce-Talsma DO, MS MEdL, FNAOME Health Policy Fellowship 2014-2015 INTRODUCTION HEALTH CARE COSTS ASSOCIATED WITH GUN VIOLENCE INTENDED CONSEQUENCES & SUPPORTING STAKEHOLDERS CONCLUSION American taxpayers pay half a billion a year for gunshot-related Intended consequences of the bill Gun violence continues to be a public safety issue affecting the lives and health of First introduced by Rep. Kelly (D-IL-2) in 2013-2014 (113th Congress) as emergency department visits and hospital admissions according to the Collect data to improve gun safety and decrease gun violence and identify the population as well as directly contributing to health care costs, yet current HR 2456, the Bill “To require the Surgeon General of the Public Health Urban Institute. factors that may be addressed through federal or local initiatives to decrease data about gun violence is lacking. Service to submit to Congress an annual report on the effects of gun the impact of gun violence on society and to improve public safety. 2010 statistics demonstrated hospital costs totaled $669.2 million11 violence on public health” expired at the end of the Congressional 36,341 emergency room visits12 We can look to the example of research and Motor Vehicle Accident (MVA) data session. HR 224 was re-introduced in the 114th Congress (2015-2016) The American College of Physicians 25,024 hospitalizations due to firearm assault injuries12 which led to the implementation of injury prevention initiatives and a subsequent and was referred to the Committee on Energy and Commerce.2 Recommends counselling on guns in the home, universal background Greater than 43% of gunshot victims are males ages 15-2412 decrease in MVA deaths. -

Voting from the Rooftops

VOTING FROM THE ROOFTOPS How the Gun Industry Armed Osama bin Laden, other Foreign and Domestic Terrorists, and Common Criminals with 50 Caliber Sniper Rifles Violence Policy Center The Violence Policy Center is a national non-profit educational organization that conducts research and public education on firearms violence and provides information and analysis to policymakers, journalists, grassroots advocates, and the general public. The Center examines the role of firearms in America, analyzes trends and patterns in firearms violence, and works to develop policies to reduce gun- related death and injury. This study was authored by VPC Senior Policy Analyst Tom Diaz. This study was funded with the support of The David Bohnett Foundation, The Center on Crime, Communities & Culture of the Open Society Institute/Funders’ Collaborative for Gun Violence Prevention, The George Gund Foundation, The Joyce Foundation, and The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Past studies released by the Violence Policy Center include: • Shot Full of Holes: Deconstructing John Ashcroft’s Second Amendment (July 2001) • Hispanics and Firearms Violence (May 2001) • Poisonous Pastime: The Health Risks of Target Ranges and Lead to Children, Families, and the Environment (May 2001) • Where’d They Get Their Guns?—An Analysis of the Firearms Used in High-Profile Shootings, 1963 to 2001 (April 2001) • Every Handgun Is Aimed at You: The Case for Banning Handguns (March 2001) • From Gun Games to Gun Stores: Why the Firearms Industry Wants Their Video Games on -

Should Mexico Adopt Permissive Gun Policies: Lessons from the United States

Esta revista forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM http://www.juridicas.unam.mx/ https://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx/bjv https://revistas.juridicas.unam.mx/ http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iij.24485306e.2019.1.13127 exican M Review aw New Series L V O L U M E XI Number 2 SHOULD MEXICO ADOPT PERMISSIVE GUN POLICIES: LESSONS FROM THE UNITED STATES Eugenio WEIGEND VARGAS* David PÉREZ ESPARZA** ABSTRACT: After a recent increase in violence, policy makers and advocates in Mexico have proposed new firearm legislation that would shift Mexican gun policies towards a more permissive approach. Following the argument of ‘self- defense’, these initiatives would facilitate citizens’ access to guns by allowing them to carry firearms in automobiles and businesses. These initiatives have been developed without a deep analysis of the effects of permissive gun laws. In this article, the authors present an assessment of what Mexican policymak- ers and advocates should be aware of regarding permissive gun laws using the example of the United States, the nation with the highest rate of gun ownership in the world and where these policies are already in effect. KEYWORDS: Permissive Gun Laws, Self-Defense, National Rifle Association, Second Amendment, Gun Violence. RESUMEN: Ante el reciente incremento de violencia en México, algunos to- madores de decisión y grupos ciudadanos han comenzado a debatir propuestas legislativas que modificarían la política de armas en México hacia un enfoque más permisivo. Bajo el argumento de ‘legítima defensa’, estas iniciativas, por ejemplo, facilitarían el acceso a armas de fuego a los ciudadanos al permitírseles portar armas en automóviles y negocios. -

Reducing Youth Gun Violence: an Overview of Programs and Initiatives

T O EN F J TM U R ST U.S. Department of Justice A I P C E E D B O J C S F A V Office of Justice Programs F M O I N A C I J S R E BJ G O OJJ DP O F PR Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention JUSTICE Reducing Youth Gun Violence: An Overview of Programs and Initiatives PROGRAM REPORT Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) was established by the President and Con- gress through the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (JJDP) Act of 1974, Public Law 93–415, as amended. Located within the Office of Justice Programs of the U.S. Department of Justice, OJJDP’s goal is to provide national leadership in addressing the issues of juvenile delinquency and improving juvenile justice. OJJDP sponsors a broad array of research, program, and training initiatives to improve the juvenile justice system as a whole, as well as to benefit individual youth-serving agencies. These initiatives are carried out by seven components within OJJDP, described below. Research and Program Development Division Information Dissemination Unit informs individuals develops knowledge on national trends in juvenile and organizations of OJJDP initiatives; disseminates delinquency; supports a program for data collection information on juvenile justice, delinquency preven- and information sharing that incorporates elements tion, and missing children; and coordinates program of statistical and systems development; identifies planning efforts within OJJDP. The unit’s activities how delinquency develops and the best methods include publishing research and statistical reports, for its prevention, intervention, and treatment; and bulletins, and other documents, as well as overseeing analyzes practices and trends in the juvenile justice the operations of the Juvenile Justice Clearinghouse. -

Curio & Relic/C&R Information for Collectors

Page 1 JULY 2020 Columns & News The GunNews is the official monthly publication of the Washington 4 Legislation & Politics–Joe Waldron Arms Collectors, an NRA-affiliated organization located at 1006 15 Straight From the Holster–JT Hilsendeger Fryar Ave, Bldg D, Sumner, WA 98390. Subscription is by member- 18 Is There a Mouse in Your House?–Tom Burke ship only and $15 per year of membership dues goes for subscrip- 22 Short Rounds tion to the magazine. Features Managing Editor–Philip Shave 3 Curio & Relic License Information–Editor Send editorial correspondence, Wanted Dead or 8 The Red 9–Bill Hunt Alive ads, or commercial advertising inquiries to: 10 The Chinese .45 Broomhandle–J.W. Mathews [email protected] 12 A Broomhandle By Any Other Name–Phil 7625 78th Loop NW, Olympia, WA 98502 Shave (360) 866-8478 Assistant Editor–Bill Burris For Collectors Art Director/Covers–Bill Hunt Cover–Art Director Copy Editors–Bob Brittle, Bill Burris, Forbes 24 Wanted: Dead or Alive Bill Hunt provided Freeburg, Woody Mathews 32 Show Calendar both the cover photo and article on the Member Resources Mauser C96 Red 9, see pp. 8-9, 16-17. CONTACT THE BUSINESS OFFICE FOR: 28 Board Minutes n MISSING GunNews & DELIVERY PROBLEMS 30 Member Info n TABLE RESERVATIONS n CHANGE OF ADDRESS n TRAINING n CLUB INFORMATION, MEMBERSHIP Club Officers (425) 255-8410 voice President — Bill Burris (425) 255-8410 253-881-1617FAX Vice President — Boyd Kneeland (425) 643-9288 Office Hours: 9a.m.–5p.m., M–TH Secretary — Forbes Freeburg (425) 255-8410 closed holidays Treasurer — Holly Henson (425) 255-8410 Walk-in Temporarily Closed Due to Immediate Past President — Boyd Kneeland (425) 643-9288 Virus Club Board of Directors SEND OFFICE CORRESPONDENCE TO: Scott Bramhall (425)255-8410 P.O. -

Centralized Firearms Background Check Program Implementation Plan

CENTRALIZED FIREARMS BACKGROUND CHECK PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION PLAN December 1, 2020 Developed by: Scott Came Consulting LLC in partnership with SEARCH and Briskin Consulting LLC THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK CENTRALIZED FIREARMS BACKGROUND CHECK PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 3 Program Overview ......................................................................................................... 4 System Description........................................................................................................ 5 Assumptions and Constraints ........................................................................................ 6 Scope and Organizational Assumptions ........................................................................ 6 Assumptions Concerning the Volume of Background Checks ....................................... 8 Budget Assumptions .................................................................................................... 11 Technology Assumptions............................................................................................. 12 Constraints .................................................................................................................. 13 Program Organization ................................................................................................ -

A Content Analysis of the Coverage of Gun Trafficking Along

A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE COVERAGE OF GUN TRAFFICKING ALONG THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDER A Dissertation by OMAR CAMARILLO Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Holly Foster Committee Members, Sarah N. Gatson Jane Sell Alex McIntosh Head of Department, Jane Sell May 2015 Major Subject: Sociology Copyright 2015 Omar Camarillo ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzed how the media on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border portrayed the issue of gun trafficking’s into Mexico and its impact on Mexico’s border violence. National newspapers from both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border were analyzed from January 2009 through January 2012, The New York Times for the U.S. and El Universal for Mexico, which resulted in a sample of 602 newspaper articles. Qualitative research methods were utilized to collect and analyze the data, specifically content analysis. Drawing on a theoretical framework of social problems and framing this study addressed how gun trafficking along the U.S.-Mexico border impacted the drug related violence that is ongoing in Mexico, how gun trafficking was portrayed as a social problem by the media, and how the media depicted the victims of drug related violence. This study revealed six framing devices, “the blame game,” “worthy and unworthy victims,” “positive aspects of gun trafficking,” “negative aspects of gun trafficking,” “indirect mention of gun trafficking,” and “direct mention of gun trafficking” that were utilized by The New York Times and El Universal to discuss and frame the issue gun trafficking into Mexico and its impact on Mexico’s border violence. -

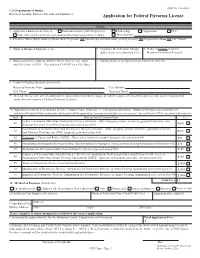

Application for Federal Firearms License

U.S. Department of Justice OMB No. 1140-0018 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Application for Federal Firearms License For ATF Use Only 1. Name of Owner or Corporation (If partnership, include name of each partner) 2. Trade or Business Name, if any 3. Employer Identification Number (EIN#) or 4. Name of County in Which Social Security Number (SSN is Voluntary) Business is Located 5. Business Address (RFD or street number, city, State, and ZIP 6. Mailing Address (If different from address in item #5) code) (NOTE: The business address CANNOT be a P.O. Box.) 7. Contact Numbers (Include Area Code) Business Phone Fax Number Cell Phone 24 Hour Emergency # (If different) 8. Applicant's Business is (Select one) Individually Owned A Partnership A Corporation Other (Specify) 9. Describe Specific Activity Applicant is Engaged in, or Intends to Engage in, Which Requires a Federal 10. Do You Intend to Engage in Firearms License. (Sale of ammunition alone does not require a license.) Business as a Pawnbroker? Yes No 11. Application is Made For a License Under 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44 as a: (Place an "X" in the appropriate box. Submit the fee noted next to the box with the application. Licenses are issued for a 3-year period. See instruction #13 for payment information.) Type Description of License Type Fee Dealer (01), Including Pawnbroker (02), in Firearms Other Than Destructive Devices (Includes: Rifles, Shotguns, Pistols, 01/02 $200 Revolvers, Gunsmith activities and National Firearms Act (NFA) Weapons) 06 Manufacturer of Ammunition -

Application for Federal Firearms License

OMB No. 1140-0018 U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Application for Federal Firearms License Part A 1. Applicant’s Business/Activity is: Individual Owner (Sole Proprietor) Partnership Corporation LLC Collector (which can be an individual/partnership/corporation or LLC) Other (specify) 2. Licensee Name (Enter name of Owner/Sole Proprietor OR Partnership (include name of each partner) OR Corporation Name OR LLC Name) 3. Trade or Business Name(s), if any 4. Employer Identification Number 5. Name of County in which (EIN), if any (see definition #17) Business/Activity is Located 6. Business/Activity Address (RFD or Street Number, City, State, 7. Mailing Address (if different from address in item #6) and ZIP Code) (NOTE: This address CANNOT be a P.O. Box.) 8. Contact Numbers (Include Area Code) Business/Activity Phone Fax Number Cell Phone Business Email 9. Describe the specific activity applicant is engaged in or intends to engage in, which requires a Federal Firearms License (sale of ammunition alone does not require a Federal Firearms License). 10. Application is made for a license under 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44 as a: (Place an “X” in the appropriate box(es). Multiple license types may be selected- see instruction #8. Submit the fee noted next to the box(es) with the application. Licenses are issued for a 3-year period. See instruction #5 for payment information). Type Description of License Type Fee Dealer in Firearms Other than Destructive Devices (Includes: rifles, shotguns, pistols, revolvers,