Vocational Training for Women Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 01.12.2019To07.12.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 01.12.2019to07.12.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 SOMALAYAM H, Cr. No. 1748 AYMANAM KOTTAYAM 1 MAHESH PS SOMAN 34 MARYATHURUTHU 01.12.19 U/s 283 IPC SABU SUNNY Station Bail BHAGOM WEST PS PO, AYMANAM 12:44 Hrs 120(b) KP Act CHAMAKKALA H, Cr. No. 1750 ANILKUMAR CHERUVAANDOOR, KOTTAYAM 2 ANANDHAN 43 KUDAMALOOR 01.12.19 U/s.279 IPC & SABU SUNNY Station Bail CA ETTUMANOOR, WEST PS 12:33 Hrs 185 MV Act KOTTAYAM MOOLAYIL H, PANNIKKOTTU PADY, BIG BAZAAR Cr. No. 1751 KOTTAYAM 3 BINOY MON JACOB 46 01.12.19 SABU SUNNY Station Bail MEENADOM, AREA U/s. 283 IPC WEST PS 20:15 Hrs KOTTAYAM THADATHIL PARAMBIL TONY THIRUNAKKAR Cr. No. 1753 KOTTAYAM 4 THOMAS 53 H, KODIMATHA , 02.12.19 ASI DILEEP Station Bail THOMAS A U/s. 151 CrPC WEST PS MARKET BHAGOM, 13:17 Hrs CHUNGATHUMAPPAT HIL H, PATHINANCHIL Cr. No. 1754 KOTTAYAM 5 MAHIN AZAD AZAD 26 KADAVU, KARAPPUZHA 02.12.19 ASI DILEEEP Station Bail U/s. 151 CrPC WEST PS KARAPPUZHA, 13:53 Hrs KOTTAYAM KRISHNANGIRI H, Cr. No. 1755 SURESHKUMA KAVUMPADY VAYASKARAKK U/s. KOTTAYAM 6 GOKUL 20 02.12.19 SREEJITH T Station Bail R BHAGOM, UNNU. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 16.08.2020To22.08.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 16.08.2020to22.08.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 ADIVAKKAL H, Cr. No. 924/20 MALARIKKAL KOTTAYAM BAILED BY 1 ANANTHU AJIKUMAR 26 M MALARIKKAL 16.08.20 U/s. 118(A) KP SREEJITH T BHAGOM, VELOOR WEST PS POLICE 172:35 Hrs Act VILLEGE KATTILAMKAADU H, Cr. No. 924/20 KAMAL KOTTAYAM BAILED BY 2 SUDHEESH 30 M CHOORAKKAVU MALARIKKAL 16.08.20 U/s. 118(A) KP SREEJITH T KUMAR WEST PS POLICE TEMPLE, ARPOOKARA 172:35 Hrs Act PADAMATTUNKAL H, Cr. No. 924/20 VATTAMOODU KOTTAYAM BAILED BY 3 SUBI BINOY 29 M MALARIKKAL 16.08.20 U/s. 118(A) KP SREEJITH T PALAM BHAGOM, WEST PS POLICE 172:35 Hrs Act NATTASSERY Cr. No. 926/20 ELLUKALAKALATHIL H, U/s. Sec.5 RW MATHAN KOTTAYAM BAILED BY 4 SAJI 52 M MOOLAVATTOM PO, MARKET Jn. 17.08.20 4(2)(h) & ANILVARGHESE CHANDI WEST PS POLICE MOOLEDOM 19:35 Hrs 3(b),3(f) of KEPDO Cr. No. 927/20 THENGUMPARAMBIL U/s. Sec.5 RW ABDUL KOTTAYAM BAILED BY 5 JALEEL 27 M H, KUMMANAM PO, MARKET Jn. 17.08.20 4(2)(h) & ANILVARGHESE RASHEED WEST PS POLICE KOTTAYAM 19:45 Hrs 3(b),3(f) of KEPDO Cr. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 20.12.2020To26.12.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 20.12.2020to26.12.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kolakkattu H, Cr. No. 1478 Male & Mariyappally Parechal 25-12-2020 West Police JFCM-III Court 1 Shijo Mohan U/s. 15 (c) Anilkumar AS M Muttambalam, Bhagom 17:43 Hrs. Station Kottayam Abkari Act. Nattakom Vattapparambil H Cr. No. 1478 Male & Karappuzha 16-il Chira Parechal 25-12-2020 West Police JFCM-III Court 2 Unnikrishnan Raveendran U/s. 15 (c) Anilkumar AS M Bhagom Veloor Bhagom 17:43 Hrs. Station Kottayam Abkari Act. Villege. Sathy Nivas Cr. No. 1477 Male & Ambadikkavala 25-12-2020 West Police JFCM-III Court 3 Sajay Mohan Mohandas Thiruvathukkal Veloor U/s. 15 (c) Suresh T SI M Bhagom 17:43 Hrs. Station Kottayam V Abkari Act. Puthanpurayil H Cr. No. 1476 Male & Thiruvathukkal 25-12-2020 West Police JFCM-III Court 4 Sherin 35 KK Rajeev Karappuzha 16 il chira U/s. 15(c) Suresh T SI M Baipass 17:11 Hrs. Station Kottayam Veloor Bhagom. Abkari Act Puthanpurayil H Cr. No. 1476 Male & 25-12-2020 West Police JFCM-III Court 5 Vishnu Bhabu Babu Karappuzha 16 il chira Thiruvathukkal U/s. 15(c) Suresh T SI M 17:11 Hrs. Station Kottayam Veloor Abkari Act Kulathappallil H Santhosh Male & Kumaramkunnu Ambadikkavala 25-12-2020 Cr. -

Journal Final.Pmd

ISSN: 2249 - 7862 Aureole, Vol. VII, December 2015, PP 81-92 A STUDY ON THE RESOURCES OF UZHAVOOR GRAMA PANCHAYAT, KOTTAYAM(DT) KERALA *Prof. Stephen Mathew Abstract The Present study mainly focused on developing entrepreneurial policies for rural development with special emphasis on HRD. It shares how one can do meaningful and satisfying R&D work even in a small rural town like Uzhavoor. Progress in understanding the process of relationship between the resources and the scope of entrepreneurship may help the development of new managerial approaches and innovative administrative arrangements to facilitate the collaboration between entrepreneurial individuals and the organizations in which they are willing to exert their entrepreneurship. Keywords : entrepreneur, entrepreneurship, Participatory rural appraisal, Village Agro Ecological Information *Assistant Professor, PG Dept. of Commerce, St.Stephen's College, Uzhavoor, E mail: [email protected] Aureole 2015 81 Introduction Uzhavoor Grama Panchayath is historically important as it is the birth place of the tenth President of India K. R. Narayanan. He was born and grew up in this small village. His schooling days were really challenging as he was hailing from the most backward community and also the communal structure of the then society was so complex and was dominated by local feudal landlords on whom the majority depended for livelihoods. So far no serious study was conducted on the socio-political and economic changes occurred in this village, where thousands are financially well equipped today but still not willing to take any enterprenrial initiative. Total Territory of the Panchayath is 25.05 Sq KMs. Till 1972 the head quarters of the Uzhavoor panchayat was in Veliyannoor. -

Dairy Deptt Handbook CC-2019 FINAL NEW Edited.Indd

1 2 3 4 5 Introduction (Genesis of the Deptt): 1 Primary Focus Areas 1 The organogram of the Department 3 Manpower status of employees in various establishments of Dairy Development, Assam 3 Dairy infrastructure and organized dairy clusters in various districts 10 ONGOING SCHEMES 39 SOPD (State Own Priority Development) Schemes Details of schemes implemented by Dairy Development, Assam Implementation of Milk Village Scheme Achievement report of Dairy Development, Assam during the period May, 2016 to May, 2017 46 AACP & AACP-AF 52 APART 57 Rastriya Krishi Vikash Yojana (RKVY) 64 OTHER FINANCING SCHEMES UNDER GOVT OF INDIA FOR DAIRY SECTOR 69 Implemented through NABARD: 1. Dairy Entrepreneurship Development Scheme (DEDS) 2. Area Development Scheme (ADS) on Dairy Sector Project Implemented by Ministry of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fisheries, Govt. of India: 88 a. National Project for Dairy Development (NPDD) Milk Union & Dairy Cooperative Society-Guidelines 96 Guidelines for Dairy Cooperative Society(DCS) Formation 96 Dairy Education 97 Proile and contact details of Dairy Oficers under Dairy Development, Assam 98 Whom to Contact for- 101 RTI related matters Web Related Matters Assam Cooperative Societies Act, 2007 102 Web Link-Food Safety & Standards Act,2006 and FSS Rules,2011 174 8 Handbook of Dairy Development Department Introduction (Genesis of the deptt.): The Dairy Development Scheme, Assam had been originally sanctioned in 1960 and implemented during February, 1961 i.e. at the fag end of 2nd Five Year Plan under A.H. & Veterinary Department. The Object of the scheme was to develop the Dairy industry in the state through establishment of Town Milk Supply Scheme (TMSS) almost in all important towns of Assam to feed the consumers hygienic & clean milk at reasonable price at their door steps. -

Kottayam District 2014

List of NGC Schools of Kottayam District 2013-14 Sl.No Head of Name of the School 1 HeadmasterInstitution G.L.P.S, Pangada, Kottayam 2 Headmaster MDLPS,Pampady,Kottayam 3 The Principal Vivekananda Public School Pampady 4 Headmaster Alphonsa G.H.S. Vakakkad, Moonnilavu. P.O, Kottayam 5 The Principal Aravinda Vidya Mandir, Anickad P.O, Kottayam 6 The Principal A.K.J.M.H.S.S, Kanjirappally, Kottayam 7 The Principal Baker Vidyapeeth, Baker Hills, Kottayam -686001 8 Headmaster Govt.HSS Kudamaloore PO Kottayam 9 The Principal Belmount E.M.School, Manipuzha, Nattakom 10 Headmaster B.I.G.H.S, Pallom, Kottayam – 686007 11 Headmaster Baker Memorial G.H.S, Kottayam – 686001 12 The Principal Chavara Public School, Pala, Kottayam- 686575 13 The Principal Chinmaya Vidyalaya, Illickal, Kottayam 14 Headmaster St. Joseph’s G.H.S, Mattakkara, Moozhoor. P.O, Kottayam 15 Headmaster St.Mary’s U.P.S, Kalathoor P.O, Kottayam 16 The Principal BMMEM Sr.Sec.School Pothenpuram PO,Pampady 17 Headmaster Amritha HS,Moolavattom PO,Kottayam 18 The Principal Cross Roads E.H.S, Pampady. P.O, Kottayam 19 Headmaster C.S.U.P.S, Madappally. P.O,Changanacherry, Kottayam 20 Headmaster C.M.S.H.S, Olessa P.O, Kottayam 21 Headmaster C.M.U.P.S, Kattampack, Kottayam 22 The Principal Dr. Z.H.M. Bharathiya V.V, Perunna P.O, Changanachery 23 The Principal De Paul H.S.S, Nazerath Hill P.O, Kuravilangad 24 Headmaster Don Bosco High School, Puthuppally P.O, Kottayam 25 The Principal Excelsior Eng. School,Illickal, Kottayam (West) 26 The Principal Emmanuel’s H.S.S, Kothanalloor.P.O, Kottayam 27 The Principal Good Shephered Public School, Madappally. -

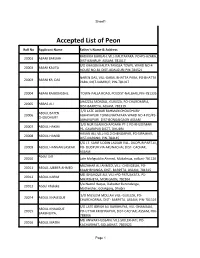

Accepted List of Peon

Sheet1 Accepted List of Peon Roll No Applicant Name Father's Name & Address RADHIKA BARUAH, VILL-KALITAPARA. PO+PS-AZARA, 20001 ABANI BARUAH DIST-KAMRUP, ASSAM, 781017 S/O KHAGEN KALITA TANGLA TOWN, WARD NO-4 20002 ABANI KALITA HOUSE NO-81 DIST-UDALGURI PIN-784521 NAREN DAS, VILL-GARAL BHATTA PARA, PO-BHATTA 20003 ABANI KR. DAS PARA, DIST-KAMRUP, PIN-781017 20004 ABANI RAJBONGSHI, TOWN-PALLA ROAD, PO/DIST-NALBARI, PIN-781335 AHAZZAL MONDAL, GUILEZA, PO-CHARCHARIA, 20005 ABBAS ALI DIST-BARPETA, ASSAM, 781319 S/O LATE AJIBAR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY ABDUL BATEN 20006 ABHAYAPURI TOWN,NAYAPARA WARD NO-4 PO/PS- CHOUDHURY ABHAYAPURI DIST-BONGAIGAON ASSAM S/O NUR ISLAM CHAPGARH PT-1 PO-KHUDIMARI 20007 ABDUL HAKIM PS- GAURIPUR DISTT- DHUBRI HASAN ALI, VILL-NO.2 CHENGAPAR, PO-SIPAJHAR, 20008 ABDUL HAMID DIST-DARANG, PIN-784145 S/O LT. SARIF UDDIN LASKAR VILL- DUDPUR PART-III, 20009 ABDUL HANNAN LASKAR PO- DUDPUR VIA ARUNACHAL DIST- CACHAR, ASSAM Abdul Jalil 20010 Late Mafiguddin Ahmed, Mukalmua, nalbari-781126 MUZAHAR ALI AHMED, VILL- CHENGELIA, PO- 20011 ABDUL JUBBER AHMED KALAHBHANGA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, 781315 MD ISHAHQUE ALI, VILL+PO-PATUAKATA, PS- 20012 ABDUL KARIM MIKIRBHETA, MORIGAON, 782104 S/o Nazrul Haque, Dabotter Barundanga, 20013 Abdul Khaleke Motherjhar, Golakgonj, Dhubri S/O MUSLEM MOLLAH VILL- GUILEZA, PO- 20014 ABDUL KHALEQUE CHARCHORRIA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, PIN-781319 S/O LATE IDRISH ALI BARBHUIYA, VILL-DHAMALIA, ABDUL KHALIQUE 20015 PO-UTTAR KRISHNAPUR, DIST-CACHAR, ASSAM, PIN- BARBHUIYA, 788006 MD ANWAR HUSSAIN, VILL-SIOLEKHATI, PO- 20016 ABDUL MATIN KACHARIHAT, GOLAGHAT, 7865621 Page 1 Sheet1 KASHEM ULLA, VILL-SINDURAI PART II, PO-BELGURI, 20017 ABDUL MONNAF ALI PS-GOLAKGANJ, DIST-DHUBRI, 783334 S/O LATE ABDUL WAHAB VILL-BHATIPARA 20018 ABDUL MOZID PO&PS&DIST-GOALPARA ASSAM PIN-783101 ABDUL ROUF,VILL-GANDHINAGAR, PO+DIST- 20019 ABDUL RAHIZ BARPETA, 781301 Late Fizur Rahman Choudhury, vill- badripur, PO- 20020 Abdul Rashid choudhary Badripur, Pin-788009, Dist- Silchar MD. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 12.11.2017 to 18.11.2017

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 12.11.2017 to 18.11.2017 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 MK Shameer Kalukal house, 2474/17 U/S Teena 46/17 13.11.17 Si of Police 1 Sebastian Manakachira, Police Station 279,337 338 CHRY Bail from PS Sebastian F 11.00 Hrs Changanacher Perunna IPC ry Kulangara Silpa MK Shameer Ayyakuty 58/17 House, 15.11.17 2429/17 U/S Si of Police 2 Devarajan Police Station CHRY Bail from PS achary M Puzhavaathu, 10.30 Hrs 279 337 IPC Changanacher Changancherry ry 2076/17 U/S MK Shameer Puthuparamb, 40/17 15.11.17 452,332,324, Si of Police 3 Nissar Ibrahim Sanketham, Veroor, Police Station CHRY Bail from PS M 12.40 PM 294 (b)506 (ii) Changanacher Chethipuzha 34 IPC ry MK Shameer 2534/17 Vishnu 20/17 Kizhakkeputhenpura 15.11.17 Si of Police 4 Sureshkumar Police Station U/S 294 (b) CHRY Bail from PS Suresh M ckal,Perunna East 05. PM Changanacher IPC ry Hussain MK Shameer 45/17 Purayidathil,Civilstat 16.11.17 2495/17 279 Si of Police 5 Noushad Ismayil Police Station CHRY Bail from PS M ion 12.30 PM IPC Changanacher bhagom,Alapuzha ry Thekkumkara Puthenveedu, MK Shameer 22/17 Marathaman,Kallara 17.11.17 2483/17 U/S Si of Police 6 Ananthu Anilkumar Police Station CHRY Bail from PS M , 11.00 Am 323 IPC Changanacher Thiruvananthapura ry m MK Shameer Kevin Oommen Neryathra -

List of Candidates Called for Preliminary Examination for Direct Recruitment of Grade-Iii Officers in Assam Judicial Service

LIST OF CANDIDATES CALLED FOR PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION FOR DIRECT RECRUITMENT OF GRADE-III OFFICERS IN ASSAM JUDICIAL SERVICE. Sl No Name of the Category Roll No Present Address Candidate 1 2 3 4 5 1 A.M. MUKHTAR AHMED General 0001 C/O Imran Hussain (S.I. of Ploice), Convoy Road, Near Radio Station, P.O.- CHOUDHURY Boiragimath, Dist.- Dibrugarh, Pin-786003, Assam 2 AAM MOK KHENLOUNG ST 0002 Tipam Phakey Village, P.O.- Tipam(Joypur), Dist.- Dibrugarh(Assam), Pin- 786614 3 ABBAS ALI DEWAN General 0003 Vill: Dewrikuchi, P.O.:-Sonkuchi, P.S.& Dist.:- Barpeta, Assam, Pin-781314 4 ABDIDAR HUSSAIN OBC 0004 C/O Abdul Motin, Moirabari Sr. Madrassa, Vill, PO & PS-Moirabari, Dist-Morigaon SIDDIQUEE (Assam), Pin-782126 5 ABDUL ASAD REZAUL General 0005 C/O Pradip Sarkar, Debdaru Path, H/No.19, Dispur, Ghy-6. KARIM 6 ABDUL AZIM BARBHUIYA General 0006 Vill-Borbond Part-III, PO-Baliura, PS & Dist-Hailakandi (Assam) 7 ABDUL AZIZ General 0007 Vill. Piradhara Part - I, P.O. Piradhara, Dist. Bongaigaon, Assam, Pin - 783384. 8 ABDUL AZIZ General 0008 ISLAMPUR, RANGIA,WARD NO2, P.O.-RANGIA, DIST.- KAMRUP, PIN-781365 9 ABDUL BARIK General 0009 F. Ali Ahmed Nagar, Panjabari, Road, Sewali Path, Bye Lane - 5, House No.10, Guwahati - 781037. 10 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0010 Vill: Chamaria Pam, P.O. Mahtoli, P.S. Boko, Dist. Kamrup(R), Assam, Pin:-781136 11 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0011 Vill: Pub- Mahachara, P.O. & P.S. -Kachumara, Dist. Barpeta, Assam, Pin. 781127 12 ABDUL BATEN SK. General 0012 Vill-Char-Katdanga Pt-I, PO-Mohurirchar, PS-South Salmara, Dist-Dhubri (Assam) 13 ABDUL GAFFAR General 0013 C/O AKHTAR PARVEZ, ADVOCATE, HOUSE NO. -

Club Health Assessment MBR0087

Club Health Assessment for District 318 B through December 2018 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs less than two years old 132167 Changanacherry Centennial 07/05/2017 Cancelled(8*) 0 0 40 -40 -100.00% 23 1 0 None 14 90+ Days 133501 Chemmalamattom 12/27/2017 Active(1) 21 0 0 0 0.00% 21 1 2 M,VP,MC,SC 8 131994 Ettumanoor Centennial 07/04/2017 Active(1) 105 0 2 -2 -1.87% 101 1 0 2 M,SC 2 136125 Ettumanoor Town 08/14/2018 Active 23 23 0 23 100.00% 0 2 M,VP,MC,SC N/R 90+ Days 134419 Kadaplamattom 05/07/2018 Active 29 0 0 0 0.00% 0 7 2 M,VP,MC,SC N/R 134234 Koodalloor 05/22/2018 Active 26 0 0 0 0.00% 0 7 2 M,VP,SC 2 131992 Kottayam Centennial 07/04/2017 Active 25 0 3 -3 -10.71% 21 1 0 SC 0 Exc Award (,06/30/18) 131102 Kottayam Dream City 06/14/2017 Cancelled(8*) 0 0 21 -21 -100.00% 21 2 0 None 14 90+ Days -

In the Court of the Additional Sub Judge, Kottayam

IN THE COURT OF THE ADDITIONAL SUB JUDGE, KOTTAYAM. Present :- Sri. Sudheesh Kumar S, Addl. Sub Judge. Friday Friday 30 th April, 2021 10th Vysakam 1943. O.S. No.106/2015 Plaintiffs:- 1. Knanaya Catholic Naveekarana Samithy, Vaithara Building (Near Village Office), Kumarakom P.O., Kottayam- 686563 represented by its President who is also the 2nd plaintiff. 2. T.O. Joseph, aged 70 years, S/o. Ouseph, Thottumkal House, Kannankara P.O., Thannermukkam North Village, Cherthala Taluk, Alappuzha District. 3. Lukose Mathew K., aged 65 years, S/o. Mathew, Kunnumpurathu (H), Kurichithanam P.O., Kurichithanam Village, Meenachil Taluk, Kottayam District. 4. C.K. Punnen, aged 68 years, S/o. Kuruvilla, Chirayil house, Athirampuzha P.O., Kottayam Taluk, Kottayam District, represented by his Power of attorney holder V.C. Mathai. By Adv. Francis Thomas and Adv. George Thomas Defendants:- 1. The Metropolitan Archbishop, The Archeparchy of Kottayam, Catholic Metropolitan's House, Kottayam Kerala- 686001. The present Metropolitan Archbishop is Most Rev. Mar Mathew Moolakkatt. 2. The Archeparchy of Kottayam, Catholic Metropolitan's House, P.B. No. 71, Kottayam, Kerala-686001, represented by The Metropolitan Archbishop. 2 3. The Major Archbishop, Syro Malabar Major Archiepiscopal Church, Mount St. Thomas, Kakkanad P.O., P.B. No. 3110, Kochi- 682030. The present Major Archbishop is His beatitude Mar George Cardinal Alenchery. 4. Synod of the Bishop of the Syro Malabar Major Archiepiscopal Church, Mount St. Thomas, Kakkanad P.O., P.B. No. 3110, Kochi- 682030 represented by its Secretary. 5. Congregation for the Oriental Churches Via Della Conciliazione 34, 00193 Roma Italy represented by its Prefect. -

Junior Assistant-2015-16 (Final)

NAME OF SHORT LISTED CANDIDATES FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION OF JUNIOR ASSISTANT 2015-16 OF DEPUTTY COMMISSIONER'S OFFICE SONITPUR TEZPUR ROLL NAME ADDRESS DATE OF QUALIFIC OTHER CASTE NO. BIRTH ATION QUALIFICATI ON 1 Ajitav Choudhury S/O- Lt Akash Pratim 7/1/1991 HSLC Diploma in General Choudhury, Computer Vill- North Ghy, Rongmahal, PS- Changsari, PO- Rangmahal, Ghy-781030 2 Anjana Devi W/O- Sri Dhiraj 12/31/1986 BA PGDCA General Upadhyaya, (1Year) PO- Samardalani, PS- Sootea, Sonitpur 3 Amrita Talukdar D/O- Sri Binod Talukdar, 2/10/1983 HSLC DCA General Vill- Mazgaon, PO/PS- Tezpur 4 Anuradha Kalita W/o- Sri Khanindra 5/31/1979 BA 1 year computer General Saikia, Vill- Rangamati, Dist- Darrang, Pin-785429 5 Ananta Talukdar S/O- Barun talukdar, 11/30/1978 HSLC Library General Vill- Singimari, Technician/ PO- Kocharigaon, Typing English Pin-784117, Sonitpur Computer CCA 6 Atul Pachani S/O- Mr. KhaGeneral 4/30/1994 HSSLC ADCA ,Web - Pachani, Page Design Vill- Dubia, PO- Bishnupur, Dist- Dhemaji, Pin-787057 7 Amrit Das S/O- Sri Chenaram Das, 11/1/1977 HSSLC Computer SC Vill- Raidongia, Diploma PO-Aibheti, PS- Japori, Pin- 782002, Dist- Nagaon 8 Archana kalita D/O- Mr Nripen kalita, 12/27/1990 HSSLC PGDCA(1 Year) General Vill-Mathurapur(South), PO/PS- Tihu, Dist- Nalbari, Pin-781371 9 Ankana Hazarika D/O- Purnakanta 7/12/1993 BA PGDCA - Hazarika, Vill- Sonarigaon, PO- Silghat, Dist- Nagaon, 10 Arunabh Saikia S/O- Sri Amiya Kr Saikia, 6/6/1987 HSSLC Diploma in basic - Vill- Darrang College Computer Road, PO/PS- Tezpur 11 Ashim Das S/O- Sri Uma Kanta Das, 1/25/1992 BA Diploma in - Vill- Amloga, Computer PO- Uttar Amloga, PS- Chariduar.