Association for Consumer Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Visit of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip (Great Britain) (4)” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 51, folder “7/7-10/76 - State Visit of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip (Great Britain) (4)” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON Proposed guest list for the dinner to be given by the President and Mrs. Ford in honor of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, on Wednesday, July 7, 1976 at eight 0 1 clock, The White House. White tie. The President and Mrs. Ford Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and The Prince Philip Balance of official party - 16 Miss Susan Ford Mr. Jack Ford The Vice President and Mrs. Rockefeller The Secretary of State and Mrs. Kissinger The Secretary of the Treasury and Mrs. Simon The Secretary of Defense and Mrs. Rumsfeld The Chief Justice and Mrs. Burger General and Mrs. -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

5Th Annual Heroes4heroes Los Angeles Police Memorial Foundation Celebrity Poker Tournament & Casino Night Party Sunday November 17, 2019 @ 4Pm

5th Annual Heroes4Heroes Los Angeles Police Memorial Foundation Celebrity Poker Tournament & Casino Night Party Sunday November 17, 2019 @ 4pm Over 50 celebrities and community members will gather together to play poker, casino games and enjoy a party to help raise money for the children and widows of LAPD Officers that have been killed in the line of Duty. Without the help of the foundation many of their kids will not have the opportunity to go to college, will lack basic funds for sporting activities or even medical costs. We hope you can join us to support this worthy cause. *poker*casino games*party*cocktails*music*food*auction*raffle*photobooth*red carpet arrivals and more… Since its inception in 1972, the Foundation has granted more than $18 million for medical, funeral and educational expenses without any taxpayer money. Past Celebrity supporters include: Jack Nicholson, Jerry West, Wayne Gretzky, Mark Wahlberg, Elton John, Sugar Ray Leonard, Vin Scully, Dennis Quaid, Kelsey Grammer, Eddie Van Halen, Samuel L. Jackson, Richard Dreyfuss, Chris O'Donnell, George Lopez, Larry King, Tommy Lasorda, Oscar de la Hoya, Rihanna, Ray Romano, Betty White, Andy Garcia, Luke Wilson, Gene Simmons, Marlon Wayans, Backstreet Boys, Paula Abdul, David Hasselhoff, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Bob Newhart, Telly Savalas, Johnny Grant, James Gandolfini and many more. Each year, superstars from TV, Film, Music and Sports join together to show support for the men & women who serve their community. This star-studded event is covered by mainstream media worldwide and is great exposure for sponsors who participate. Our events are covered by top mainstream entertainment media such as People, US Weekly, OK Magazine, Star, Extra, E Entertainment, Access Hollywood, Daily Mail, Extra, Variety, Hollywood Reporter and worldwide news outlets including Yahoo Finance, Yahoo Sports, Market Watch/Dow Jones, Reuters, Bloomberg Business Week, Fox News and more. -

Gene Kearney Papers, 1932-1979 (Collection PASC.207)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7d5nf5r2 No online items Finding Aid for the Gene Kearney Papers, 1932-1979 (Collection PASC.207) Finding aid prepared by J. Vera and J. Graham; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Gene Kearney PASC.207 1 Papers, 1932-1979 (Collection PASC.207) Title: Gene Kearney papers Collection number: PASC.207 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 7.5 linear ft.(15 boxes.) Date (inclusive): 1932-1979 Abstract: Gene Kearney was a writer, director, producer, and actor in various television programs and motion pictures. Collection consists of scripts, production information and clippings related to his career. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Kearney, Gene R Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Portions of this collection are restricted. Consult finding aid for additional information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Record World

record tWODedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Music & Record Industry x09664I1Y3 ONv iS Of 311VA ZPAS 3NO2 ONI 01;01 3H1 June 21, 1970 113N8V9 NOti 75c - In the opinion of the eUILIRS,la's wee% Tne itmuwmg diCtie SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK EPIC ND ARMS CAN EVER HOLD YOU CORBYVINTON Kenny Rogers and the First Mary Hopkin sings Doris Nilsson has what could be Bobby Vinton gets justa Edition advise the world to Day'sphilosophicaloldie, his biggest, a n dpossibly littlenostalgicwith"No "TellItAll Brother" (Sun- "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever hisbest single,a unique Arms Can Ever Hold You" beam, BMI), and it's bound WillBe, WillBe)" (Artist, dittyofhis own devising, (Gil, BMI),whichsounds tobe theirlatestsmash ASCAP), her way (A p p le "Down to the Valley" (Sun- just right for the summer- (Reprise 0923). 1823). beam, BM!) (RCA 74-0362). time (Epic 5-10629). SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK SORRY SUZANNE (Jan-1111 Auto uary, Embassy BMI) 4526 THE GLASS BOTTLE Booker T. & the M. G.'s do Canned Heat do "Going Up The Glass Bottle,a group JerryBlavat,Philly'sGea something just alittledif- the Country" (Metric, BMI) ofthreeguysandthree for with the Heater,isal- ferent,somethingjust a astheydo itin"Wood- gals, introduce themselves ready clicking with "Tasty littleliltingwith"Some- stock," and it will have in- with "Sorry Suzanne" (Jan- (To Me),"whichgeators thing" (Harrisongs, BMI) creasedmeaningto the uary, BMI), a rouser (Avco andgeatoretteswilllove (Stax 0073). teens (Liberty 56180). Embassy 4526). (Bond 105). ALBUM PICKS OF THE WEEK DianaRosshasherfirst "Johnny Cash the Legend" "The Me Nobody Knows" "The Naked Carmen" isa solo album here, which is tributed in this two -rec- isthe smash off-Broadway "now"-ized versionofBi- startsoutwithherfirst ord set that includes' Fol- musical adaptation of the zet's timeless opera. -

Power? Today's Can Find the Right Vehicles

40 A S K T O N I by TONI REINHOLD What has happened to handsome TV holds promise, though, if actors leading men like Clark Gable, Robert like David Hasselhoff and Tom Selleck Taylor and Tyrone Power? Today's can find the right vehicles. actors don’t compare In looks, and But don't forget that beauty is skin D o to d a y ’s even their acting abilities are sus deep, and good acting ability runs to pect. — E.S., Fort Thomas, Ky. the bone. Be kind. Actors with looks that take one's Did Lew Ayres play the part of an breath away are almost as rare as fine elderly man in the film “Of Mice and a c to rs films these days, but there are a few. Men”? — E.D.H., South Bend, Ind. Robert Redford, for example, has both Lew Ayres played an elderly gent in looks and ability, and Harrison Ford the 1981 TV remake of “Of Mice and c o m p a re ? brings a ruggedly handsome presence Men," which starred Robert Blake and to the screen. We just don't see Randy Quaid. The original 1939 Stein enough of them. beck novel featured Lon Chaney Jr. Bev, Laurel, Michele & Urbin POWERVAC are proud to of announce that Prince George Colleen Katrinchuk Dirty Furnaces & Ducts? has joined our staff C all: Colleen invites all her friends & clients to visit her at: Power Yac Lower floor of “We also clean fireplaces" ^SBrunsuftehBowie’s Fashion at 562-2240 hair design 300 Brunswick 562-5255 Sears installed siding Free yourselt Irom the time and cost involved in continual horns maintenance. -

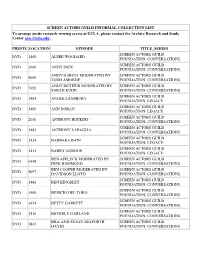

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS -

Animals in Media Genesis Honors the Best

12 | THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES Animals in Media Genesis Honors the Best The HSUS President & CEO Wayne Pacelle, actor James Cromwell, and Joan McIntosh. Genesis Awards founder Gretchen Wyler. he power of the media to project the joy of celebrating animals Wyler came up with the idea for an awards show because she strongly Tand to promote their humane treatment was demonstrated believed that honoring members of the media encourages them to anew at the 20th Anniversary HSUS Genesis Awards staged before spotlight more animal issues, thus increasing public awareness and a glittering audience at California’s Beverly Hilton Hotel in March. compassion. The annual event began as a luncheon with 140 attendees The ceremonies presented awards in 21 print, television, and film and quickly grew into a large gala in Beverly Hills, California, with categories and honored dozens of talented individuals from news more than 1,000 guests. and entertainment media. Beginning with the first ceremony, Genesis Awards entries have The annual celebration recaptured some of the extraordinary events been submitted by the public and by media professionals. Categories that occurred in 2005, from the massive effort to rescue animals span television, film, print, radio, music, and the arts. The awards abandoned in the wake of Hurricane Katrina to such perennial committee chooses winners by secret ballot and the 17 committee concerns as fur, factory farming, and wildlife abuses. It also marked members are selected because of their lengthy personal histories the retirement of HSUS Vice President Gretchen Wyler, who founded in working for the animals. -

The Lollipop

The table football The Lollipop Name: Group: 1 WE ARE CURIOUS The lollipop was born to avoid children getting dirty 1. Who is León Felipe? with sweets and today it sells 18 million units a day. 2. Which is the capital of Ecuador? It is the lollipop 50th birthday. 3. Show on the map the spanish cities and the countries mentioned in the text. The lollipop was born 50 years ago as a practical and intelligent solution to avoid little children to get their hands dirty The lollipop was Theborn lollipop 50 years was ago born as 50a practical years ago and as intelligent a practical solution and intelligent to avoid solutionlittle children to avoid to get little their children hands to dirty get their hands dirty with sweets. with sweets. with sweets. Half a century later, the lollipop has become a global phenomenon. A business and commercial success that became Half a century later,Half the a centurylollipop later,has become the lollipop a global has become phenomenon. a global A phenomenon.business and commercial A business andsuccess commercial that became success that became fashionable thanks to its ingenious simplicity in the sophisticated industry of sweeties. fashionable thanksfashionable to its ingenious thanks simplicity to its ingenious in the sophisticated simplicity in the industry sophisticated of sweeties. industry of sweeties. Enric Bernat, the creator, invented the ultra-famous sweet stick in 1958. Everyday 18 million units come out on the Enric Bernat, the Enriccreator, Bernat, invented the creator, the ultra-famous invented the sweet ultra-famous stick in 1958. sweet Everyday stick in 18 1958. -

Bonds IS Princess

PAGE FOUR T H E BENNETT BANNER FRIDAY, APRIL 20, 1984 M ore letters: Alumna to publish novel Nigeria defended; unity demanded by Yolanda DuRant Willa B. Player, and two of have always been healers and This letter is written in response “In Nigeria you undergo a col Bragg’s sisters had been peacemakers. People assume to quotations attributed to Omo- lege training period, something Soft-spoken, articulate and Belles. that if a person is strong, she tayo Otoki in a feature written like a technical school for two firm in her convictions are doesn’t have turmoil. So I by Vonda Long. years,” said Tayo. terms which characterize Dr. Bennett fulfilled another important need for Bragg. As told the story from her inner To the Editor: The qualification for entry into Linda Bragg, a former Belle conflicts,” she says. As a full Nigerian, I have to the Nigerian universities is a suc who teaches English at a child in Akron, Ohio, she lacked black role models be Bragg has no ideas for a straighten up so many things you cessful completion of not less than UNC-G and has a first novel did not say right; either because five courses including English and that will appear this summer. yond the figures in her im new novel, but she is “sure it mediate family. The college [inspiration] will come.” you are a half-Nigerian or be mathematics passed with Credit Bennett gave Bragg confi provided a surplus of models. She’s busy giving lectures cause you are ignorant of the at Ordinary Level General Certif dence and direction. -

County Water Conservation Measures Might Be Imposed

In an effort to break its nearly tremely valuable to have a third bitration (taking the arbitrator's two month contract negotiation party, someone who can evaluate decision without question)," he stalemate, the Newark lodge of the the issues in an objective manner," said. Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) he said. Detective Watson, Newark FOP went to Dover Wednesday to sup The city of Newark is opposed to president, was not surprised by Senate faces bill port a labor arbitration bill. the legislation, according to city Marshall's opinion of the bill. Senate bill 91 requires that manager Peter Marshall. "They have the reins now. They're municipalities and their police the ones driving the horse," he that might break forces follow the decision of an ar FOP said. Watson said he is hoping for bitrator if labor negotiations reach quick passage of the bill. an impasse. The city of Newark "An objective arbitrator who Von Koch said that currently, the and the FOP have been at an im doesn't live in Newark would not Newark Police are the lowest paid police stalemate passe since mid-February, ac have to live with his decision," full service police force in the cording to Sgt. Alex Von Koch, Marshall said. He added that the state. "We just want to get our pay chief negotiator for the FOP. bill is "inconsistent with the elec up to normal. We're far below the I Von Koch spoke out in favor of tive process." "We have elected of other police forces in the state," By GEORGE MALLET-PREVOST the legislation at a hearing con ficials," he said, referring to the ci said Von Koch. -

UNSOLD ITEMS for - Hollywood Auction Auction 89, Auction Date

26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 UNSOLD ITEMS FOR - Hollywood Auction Auction 89, Auction Date: LOT ITEM LOW HIGH RESERVE 382 MARION DAVIES (20) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS BY BULL, LOUISE, $600 $800 $600 AND OTHERS. 390 CAROLE LOMBARD & CLARK GABLE (12) VINTAGE $300 $500 $300 PHOTOGRAPHS BY HURRELL AND OTHERS. 396 SIMONE SIMON (19) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS BY HURRELL. $400 $600 $400 424 NO LOT. TBD TBD TBD 432 GEORGE HURRELL (23) 20 X 24 IN. EDITIONS OF THE PORTFOLIO $15,000 $20,000 $15,000 HURRELL III. 433 COPYRIGHTS TO (30) IMAGES FROM HURRELL’S PORTFOLIOS $30,000 $50,000 $30,000 HURRELL I, HURRELL II, HURRELL III & PORTFOLIO. Page 1 of 27 26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 UNSOLD ITEMS FOR - Hollywood Auction Auction 89, Auction Date: LOT ITEM LOW HIGH RESERVE 444 MOVIE STAR NEWS ARCHIVE (1 MILLION++) HOLLYWOOD AND $180,000 $350,000 $180,000 ENTERTAINMENT PHOTOGRAPHS. 445 IRVING KLAW’S MOVIE STAR NEWS PIN-UP ARCHIVE (10,000+) $80,000 $150,000 $80,000 NEGATIVES OFFERED WITH COPYRIGHT. 447 MARY PICKFORD (18) HAND ANNOTATED MY BEST GIRL SCENE $800 $1,200 $800 STILL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM HER ESTATE. 448 MARY PICKFORD (16) PHOTOGRAPHS FROM HER ESTATE. $800 $1,200 $800 449 MARY PICKFORD (42) PHOTOGRAPHS INCLUDING CANDIDS $800 $1,200 $800 FROM HER ESTATE. 451 WILLIAM HAINES OVERSIZE CAMERA STUDY PHOTOGRAPH BY $200 $300 $200 BULL. 454 NO LOT. TBD TBD TBD 468 JOAN CRAWFORD AND CLARK GABLE OVERSIZE PHOTOGRAPH $200 $300 $200 FROM POSSESSED.