The Naga People, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Wild Animals in Market -Tuensang, Nagaland

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.6 (2):241-253, 2013 Research Article Wildlife exploitation: a market survey in Nagaland, North-eastern India Subramanian Bhupathy1*, Selvaraj Ramesh Kumar1, Palanisamy Thirumalainathan1, Joothi Paramanandham1, and Chang Lemba2 1Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History Anaikatti (Post), Coimbatore- 641 108, Tamil Nadu, India 2C/o Moa Chang, Youth Secretary, Near Chang Baptist, Lashong, Thangnyen, Mission Compound, Tuensang, Nagaland, India *Corresponding Author ([email protected]) Abstract With growing human population, increased accessibility to remote forests and adoption of modern tools, hunting has become a severe global problem, particularly in Nagaland, a Northeast Indian state. While Indian wildlife laws prohibit hunting of virtually all large wild animals, in several parts of North-eastern parts of India that are dominated by indigenous tribal communities, these laws have largely been ineffective due to cultural traditions of hunting for meat, perceived medicinal and ritual value, and the community ownership of the forests. We report the quantity of wild animals sold at Tuensang town of Nagaland, based on weekly samples drawn from May 2009 to April 2010. Interviews were held with vendors on the availability of wild animals in forests belonging to them and methods used for hunting. The tribes of Chang, Yimchunger, Khiemungan, and Sangtam are involved in collection/ hunting and selling of animals in Tuensang. In addition to molluscs and amphibians, 1,870 birds (35 species) and 512 mammals (8 species) were found in the samples. We estimated that annually 13,067 birds and 3,567 mammals were sold in Tuensang market alone, which fetched about Indian Rupees ( ) 18.5 lakhs/ year. -

NAGALAND Basic Facts

NAGALAND Basic Facts Nagaland-t2\ Basic Facts _ry20t8 CONTENTS GENERAT INFORMATION: 1. Nagaland Profile 6-7 2. Distribution of Population, Sex Ratio, Density, Literacy Rate 8 3. Altitudes of important towns/peaks 8-9 4. lmportant festivals and time of celebrations 9 5. Governors of Nagaland 10 5. Chief Ministers of Nagaland 10-11 7. Chief Secretaries of Nagaland II-12 8. General Election/President's Rule 12-13 9. AdministrativeHeadquartersinNagaland 13-18 10. f mportant routes with distance 18-24 DEPARTMENTS: 1. Agriculture 25-32 2. Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services 32-35 3. Art & Culture 35-38 4. Border Afrairs 39-40 5. Cooperation 40-45 6. Department of Under Developed Areas (DUDA) 45-48 7. Economics & Statistics 49-52 8. Electricallnspectorate 52-53 9. Employment, Skill Development & Entrepren€urship 53-59 10. Environment, Forests & Climate Change 59-57 11. Evalua6on 67 t2. Excise & Prohibition 67-70 13. Finance 70-75 a. Taxes b, Treasuries & Accounts c. Nagaland State Lotteries 3 14. Fisheries 75-79 15. Food & Civil Supplies 79-81 16. Geology & Mining 81-85 17. Health & Family Welfare 85-98 18. Higher & Technical Education 98-106 19. Home 106-117 a, Departments under Commissioner, Nagaland. - District Administration - Village Guards Organisation - Civil Administration Works Division (CAWO) b. Civil Defence & Home Guards c. Fire & Emergency Services c. Nagaland State Disaster Management Authority d. Nagaland State Guest Houses. e. Narcotics f. Police g. Printing & Stationery h. Prisons i. Relief & Rehabilitation j. Sainik Welfare & Resettlement 20. Horticulture tl7-120 21. lndustries & Commerce 120-125 22. lnformation & Public Relations 125-127 23. -

Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Nagaland State

CLIMATE RESEARCH AND SERVICES INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES PUNE Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes over Nagaland State Met Monograph No.: ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/19(2020)/43 Pulak Guhathakurta, Sakharam Sanap, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT Met Monograph No.: ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/19(2020)/43 Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Nagaland State Pulak Guhathakurta, Sakharam Sanap, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT PUNE - 411005 1 DOCUMENT AND DATA CONTROL SHEET 1 Document Title Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Nagaland State 2 Issue No. ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/19(2020)/43 3 Issue Date January 2020 4 Security Unclassified Classification 5 Control Status Uncontrolled 6 Document Type Scientific Publication 7 No. of Pages 23 8 No. of Figures 42 9 No. of References 3 10 Distribution Unrestricted 11 Language English 12 Authors Pulak,Guhathakurta, Sakharam,Sanap, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani 13 Originating Climate Research Division/ Climate Application & Division/ Group User Interface Group/ Hydrometeorology 14 Reviewing and Director General of Meteorology, India Approving Meteorological Department, New Delhi Authority 15 End users Central and State Ministries of Water resources, agriculture and civic bodies, Science and Technology, Disaster Management Agencies, Planning Commission of India 16 Abstract India is in the tropical monsoon zone and receives plenty of rainfall as most of the annual rainfall during the monsoon season every year. However, the rainfall is having high temporal and spatial variability and due to the impact of climate changes there are significant changes in the mean rainfall pattern and their variability as well as in the intensity and frequencies of extreme rainfall events. -

Temporary, Transitional and Special Provisions 371A

PART XXI TEMPORARY, TRANSITIONAL AND SPECIAL PROVISIONS 371A. Special provision with respect to the State of Nagaland.—(1) Notwithstanding anything in this Constitution,— (a) no Act of Parliament in respect of— (i) religious or social practices of the Nagas, (ii) Naga customary law and procedure, (iii) administration of civil and criminal justice involving decisions according to Naga customary law, (iv) ownership and transfer of land and its resources, shall apply to the State of Nagaland unless the Legislative Assembly of Nagaland by a resolution so decides; (b) the Governor of Nagaland shall have special responsibility with respect to law and order in the State of Nagaland for so long as in his opinion internal disturbances occurring in the Naga Hills-Tuensang Area immediately before the formation of that State continue therein or in any part thereof and in the discharge of his functions in relation thereto the Governor shall, after consulting the Council of Ministers, exercise his individual judgment as to the action to be taken. Provided that if any question arises whether any matter is or is not a matter as respects which the Governor is under this sub-clause required to act in the exercise of his individual judgment, the decision of the Governor in his discretion shall be final, and the validity of anything done by the Governor shall not be called in question on the ground that he ought or ought not to have acted in the exercise of his individual judgment: Provided further that if the President on receipt of a report from the Governor -

DIMAPUR DISTRICT Inventory of Agriculture 2015

DIMAPUR DISTRICT Inventory of Agriculture 2015 DIMAPUR DISTRICT Inventory of Agriculture 2015 ICAR, Zone-III, Umiam Page 2 Correct Citation: Bhalerao A.K., Kumar B., Singha A. K., Jat P.C., Bordoloi, R., Deka Bidyut C., 2015, Dimapur district inventory of Agriculture, ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research Institute, Umiam, Meghalaya, India Published by: The Director, ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research Institute, Umiam (Barapani), Meghalaya-793103 Email: [email protected] Website: http://icarzcu3.gov.in Phone no. 0364-2570081 Compiled by: Dr. Anamika Sharma, Programme Coordinator Shri. Rabi Kolom, SMS (Plant Breeding) Shri. Z. James Kikon, SMS (Soil Science) Shri. Pynshailang Mawthoh, Programme Assistant (Computer Applications) Dr. Ratnakar S. Patel, Lab. Assistant Edited by: Amol K. Bhalarao, Scientist (AE) Bagish Kumar, Scientist (AE) A. K. Singha, Pr. Scientist (AE) P. C. Jat, Sr. Scientist (Agro) R. Bordoloi, Pr. Scientist (AE)\ Bidyut C. Deka, Director, ATARI Umiam Contact: Dr. Anamika Sharma (Programme coordinator) Krishi Vigyan Kendra Dimapur, ICAR Research Complex for NEH Region, Nagaland Centre, Jharnapani, Medziphema-797106, Nagaland Telephone Number: 03862-247133 Mobile Number: +919436433005 Website of KVK: www.kvkdimapur.nic.in Word Processing: Synshai Jana Cover Design: Johannes Wahlang Layout and Printing: Technical Cell, ICAR-ATARI, Umiam ICAR, Zone-III, Umiam Page 3 FOREWORD The ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research institute, Zone-III with its headquarters at Umiam, Meghalaya is primarily responsible for monitoring and reviewing of technology assessment, refinement, demonstrations, training programmes and other extension activities conducted by the Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) in North East Region, which comprises of eight states, namely Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura. -

Government of Nagaland

Government of Nagaland Contents MESSAGES i FOREWORD viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT x VISION STATEMENT xiv ACRONYMS xvii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 5 2. AGRICULTURE AND ALLIED SECTORS 12 3. EmPLOYMENT SCENARIO IN NAGALAND 24 4. INDUSTRIES, INDUSTRIALIZATION, TRADE AND COMMERCE 31 5. INFRASTRUCTURE AND CONNECTIVITY 42 6. RURAL AND URBAN PERSPECTIVES 49 7. EDUCATION, HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES 56 8. GENDER MAINSTREAMING 76 9. REGIONAL DISPARITIES 82 10. GOVERNANCE 93 11. FINANCING THE VISION 101 12. CONCLUSION 107 13. APPENDIX 117 RAJ BHAVAN Kohima-797001 December 03,2016 Message I value the efforts of the State Government in bringing out documentation on Nagaland Vision Document 2030. The Vision is a destination in the future and the ability to translate the Vision through Mission, is what matters. With Vision you can plan but with Mission you can implement. You need conviction to translate the steps needed to achieve the Vision. Almost every state or country has a Vision to propel the economy forward. We have seen and felt what it is like to have a big Vision and many in the developing world have been inspired to develop a Vision for their countries and have planned the way forward for their countries to progress. We have to be a vibrant tourist destination with good accommodation and other proper facilities to showcase our beautiful land and cultural richness. We need reformation in our education system, power and energy, roads and communications, etc. Our five Universities have to have dialogue with Trade & Commerce and introduce academic courses to create wealth out of Natural Resources with empowered skill education. -

Ground Water Information Booklet Tuensang District, Nagaland

Technical Report Series: D No: Ground Water Information Booklet Tuensang District, Nagaland Central Ground Water Board North Eastern Region Ministry of Water Resources Guwahati September 2013 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET TUENSANG DISTRICT, NAGALAND DISTRICT AT AGLANCE Sl. No. ITEMS STATISTICS 1 GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical Area (sq.km.) 4228 a. Headquarters Tuensang ii) Population (as on 2011 Census) 321427 iii) Climate a. Average Annual Rainfall 1527 mm 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY i) Major Physiographic Units Denudational Hills, Structural Hills, Intermontane valleys 3 LAND USE (sq.km.) i) Forest Area 774.68 sq km ii) Gross Cropped area 7360 hac 4 MAJOR SOIL TYPES Alluvial Soil, Non Laterite Red Soil, Forest Soil 5 IRRIGATION (2011 census) i) Net Irrigated area (Ha) 6476.49 7 PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Semi-consolidated rocks of Tertiary FORMATIONS age, metamorphic and Ophiolites. 8 HYDROGEOLOGY i) Major Water Bearing Formations Semi consolidated formations of Tertiary rocks. Ground water occurs in the form of spring emanating through cracks/ fissures/ joints etc. available in the country rock. 9 DYANMIC GROUND WATER RESOURCES (2009) in mcm i) Annual Ground Water Availability 49.71 ii) Annual Ground Water Draft 1.34 iii) Projected demand for Domestic and 2.22 Industrial Use up to 2025 iv) Stage of Ground Water Development 2.69 10 AWARENESS AND TRAINING Nil ACTIVITY 11 EFFORTS OF ARTIFICIAL RECHARGE Nil AND RAINWATER HARVESTING i) Projects Completed by CGWB (No & amount spent) ii) Projects Under technical Guidance of CGWB 12 GROUND WATER CONTROL AND Nil REGULATION i) Number of OE Blocks ii) Number of Critical Blocks iii) Number of Blocks Notified GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET TUENSANG DISTRICT, NAGALAND 1.0 Introduction Tuensang district the largest and easternmost district of Nagaland, a State in North-East India. -

Ground Water Information Booklet Kohima District, Nagaland

1 Technical Report Series: D No: Ground Water Information Booklet Kohima District, Nagaland Central Ground Water Board North Eastern Region Ministry of Water Resources Guwahati September 2013 2 KOHIMA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl No. ITEMS STATISTICS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (sq. km) 1041 ii) Administrative divisions iii) Population (2011census) 365017 iv) Average annual rainfall (mm) 2000-2500 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units High to moderate structural hills, Denudo- structural hills. Major drainages Dzuza, Dzula, Dzutsuru, Dzucharu etc 3. Total forest area (Ha) 286500 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Red Clayey soil 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL Cereals (3370 ha) CROPS, Pulses (4030 ha) Oilseeds (5260 ha) Commercial crops (2150 ha) 6. IRRIGATION (hectares) . Net Area Irrigated 7057 7. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS of CGWB (as on 31.12.2010) No of dug wells 2 No of Piezometers 1 8. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Plio-Pleistocene, Tertiary group FORMATIONS 9. HYDROGEOLOGY Major water bearing formation Semi-consolidated Tertiary formation (Pre-monsoon depth to water level 4.41 to 7.22 mbgl during 2012) (Post-monsoon depth to water level 3.98 to 4.68 mbgl during 2012) 10. GROUND WATER EXPLORATION BY CGWB Nil (as on 31.12.2013) 11. GROUND WATER QUALITY Presence of chemical constituents Generally good and suitable for more than permissible limits domestic and industrial purposes 3 12. DYNAMIC GROUND WATER RESOURCES (2009) mcm Net Ground Water availability 33.69 Net Annual Ground water draft 0.72 Stage of Ground Water Development 2.13 % 13. AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY Mass awareness programme & Nil water management training programme organized 14. -

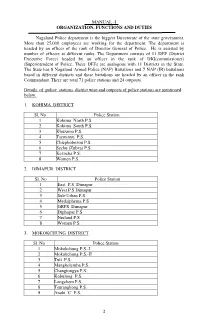

Organization, Functions and Duties

MANUAL -I ORGANIZATION, FUNCTIONS AND DUTIES Nagaland Police department is the biggest Directorate of the state government. More than 25,000 employees are working for the department. The department is headed by an officer of the rank of Director General of Police. He is assisted by number of officers at different ranks. The Department consists of 11 DEF (District Executive Force) headed by an officer in the rank of DIG(commissioner) /Superintendent of Police. These DEFs are analogous with 11 Districts in the State. The State has 8 Nagaland Armed Police (NAP) Battalions and 7 NAP (IR) battalions based in different districts and these battalions are headed by an officer in the rank Commandant. There are total 71 police stations and 24 outposts. Details of police stations district wise and outposts of police stations are mentioned below. 1. KOHIMA DISTRICT Sl. No Police Station 1 Kohima North P.S. 2 Kohima South P.S. 3 Khuzama P.S. 4 Tseminyu P.S. 5 Chiephobozou P.S. 6 Sechu (Zubza) P.S. 7 Kezocha P.S. 8 Women P.S. 2. DIMAPUR DISTRICT Sl. No Police Station 1 East P.S Dimapur 2 West P.S Dimapur 3 Sub-Urban P.S 4 Medziphema P.S 5 GRPS Dimapur 6 Diphupar P.S 7 Niuland P.S 8 Women P.S. 3. MOKOKCHUNG DISTRICT Sl. No Police Station 1 Mokokchung P.S.-I 2 Mokokchung P.S.-II 3 Tuli P.S. 4 Mangkolemba P.S. 5 Changtongya P.S. 6 Kobulong P.S. 7 Longchem P.S. 8 Tsurangkong P.S. -

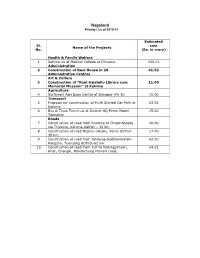

Nagaland Priority List of 2010-11

Nagaland Priority List of 2010-11 Estimated Sl. cost Name of the Projects No. (Rs. in crore) Health & Family Welfare 1 Setting up of Medical College at Dimapur 340.22 Administration 2 Construction of Rest House in 28 41.52 Administrative Centres Art & Culture 3 Construction of “Rani Gaidinliu Library cum 11.00 Memorial Museum” at Kohima Agriculture 4 Northeast Agri Expo Centre at Dimapur (Ph-II) 15.00 Transport 5 Proposal for construction of Multi Storied Car Park at 53.05 Kohima 6 Bus & Truck Terminus at District HQ Peren Model 15.00 Township Roads 7 Construction of road from Rusoma to Chiephobozou 40.00 via Thizama, Kohima district – 32 km 8 Construction of road Hebron-Jalukie, Peren district- 17.00 20 km 9 Construction of road from Jendang-Saddle-Noklak- 62.00 Pangsha, Tuensang district-62 km 10 Construction of road from Tuli to Molungyimsen, 44.01 Khar, Changki, Mokokchung Mariani road, Estimated Sl. cost Name of the Projects No. (Rs. in crore) Mokokchung District 51 km 11 Widening & Improvement of approach road from 10.00 Alongchen, Impur to Khar via Mopungchuket, Mokokchung district – 15 km 12 Construction of road Kohima to Leikie road junction 10.00 to Tepuiki to Barak, Inter-district road-10 km (MDR) Ph-III 13 Construction of road from Lukhami BRO junction to 90.00 Seyochung Tizu bridge on Satoi road, Khuza, Phughe, Chozouba State Highway junction, Inter- district road- 90 km (ODR) 14 Improvement & Upgradation of road from 5.40 Border Road to Changlangshu, Mon District-19 km 15 Construction of road from Pang to Phokphur via 12.44 -

Check List 8(6): 1163–1165, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (Available at Journal of Species Lists and Distribution

Check List 8(6): 1163–1165, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Ichthyofaunal Diversity of Dhansiri River, Dimapur, PECIES S Nagaland, India OF Biswajit Kumar Acharjee 1*, Madhurima Das 2 ISTS L 3 4 1 Faculty, Kendriya Vidyalaya, Dimapur, Nagaland, India. , Papari Borah and Jayaditya Purkayastha 2 Faculty, Department of Biotechnology, AIMT, Guwahati, Assam, India. 3 Research Scholar, Department of [email protected] Zoology, Gauhati University,Assam, India. 4 Help Earth, Guwahati, Assam, India. * Corresponding author. E- mail: Abstract: Northeastern India, one of the Ichthyofaunal hot spot areas of our country, is marked by the presence of varied freshwater fishes,a few adapted to torrential waterflow. River Dhansiri is an important river of Dimapur District of Nagaland, India, which flows through Nagaland –Assam border harbouring rich aquatic flora and fauna. Very little studies have been carried out to document the fish biodiversity of the Dhansiri river till date. In the present study an attempt has been made common.to access the piscine diversity of this river. The survey results in finding of species of 34 fishes belonging to five (5) orders, thirteen (13) families and twenty four (24) genera. Cyprniformes is the dominant order while Osteoglossiformes is the least Introduction reported from Nagaland (Ao et al. 1988). Recent literature The Northeastern region of India is considered to review describes redescription and study of Amblyceps apangi from Mokokchung (Vishwanath and Linthoingambi, et 2007) and Wokha Disrtict ( Humtsoe and Bordoloi 2009) al.be 2010).one of Athe great hotspots number of freshwaterof species havefish biodiversitybeen reported in respectively. -

Bamboo Resource Mapping of Six Districts of Nagaland

NESAC-SR-77-2010 BAMBOO RESOURCE MAPPING FOR SIX DISTRICTS OF NAGALAND USING REMOTE SENSING AND GIS Project Report Sponsored by Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Mokokchung, Nagaland Prepared by NORTH EASTERN SPACE APPLICATIONS CENTRE Department of Space, Govt. of India Umiam – 793103, Meghalaya March 2010 NESAC-SR-77-2010 BAMBOO RESOURCE MAPPING FOR SIX DISTRICTS OF NAGALAND USING REMOTE SENSING AND GIS Project Team Project Scientist Ms. K Chakraborty, Scientist, NESAC Smt R Bharali Gogoi, Scientist, NESAC Sri R Pebam, Scientist, NESAC Principal Investigator Dr. K K Sarma, Scientist, NESAC Approved by Dr P P Nageswara Rao, Director, NESAC Sponsored by Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Mokokchung, Nagaland NORTH EASTERN SPACE APPLICATIONS CENTRE Department of Space, Govt. of India Umiam – 793103, Meghalaya March 2010 Acknowledgement The project team is grateful to Sri Rajeev M. K., Dy. General Manager (Engg.) and the Dy. Manager (Forestry), Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Nagaland, for giving us opportunity to conduct the study as well as all the support during the work. Thanks are due to Mr. A. Roy, FDP and Mr. T. Zamir, Supervisor, Forest. Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Nagaland for their support and cooperation during the field work. The team is also thankful to Dr. P P Nageswara Rao, Director, NESAC for his suggestions and encouragements. The project team thanks all the colleagues of NESAC and staff of Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Nagaland, for their help and cooperation in completion of the work. Last but not least, the funding support extended by Nagaland Pulp & Paper Company Limited, Tuli, Nagaland, for the work is thankfully acknowledged.